Buddhist Philosophy in India and Ceylon

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDG323 |

| Author: | A. Berriedale Keith |

| Publisher: | Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office |

| Edition: | 2002 |

| ISBN: | 8170800641 |

| Pages: | 340 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5" X 5.5" |

Book Description

Publisher's Note:

This is one of the most systematic and thorough expositions of the Buddhist Philosophy. After giving a critical exposition to the Buddhism in Pali Cannon in its first part, it proceeds in the next two parts to discuss at length the Buddhist philosophy of both Hinayana and Mahayana Schools, with their sub-schools and declensions. Its fourth part is devoted to the study of the origin and development of Buddhist Logic.

The author has made the work as comprehensive as is possible and familiarises the readers with the vast extent and subtleties of the subject with clarity and lucidity which is so characteristic of his style. Throughout, the work is profusely documented with references from original sources and contemporary critical literature.

It is one of the 'must' books on Buddhist philosophy and is equally useful for both scholars and students. However, it was unfortunate that such a useful book remained out of print for a long time. Our reprint has been made by photo-offset process, from the original edition of 1923. We hope that it will receive the encouragement it deserves.

Preface:

To attempt a short account of Buddhist Philosophy in its historical development in India and Ceylon is a task beset with difficulties. The literature of the subject is vast in extent, and much of it buried in Tibetan and Chinese translations, which are not likely to be effectively and completely exploited for many years to come. The preliminary studies, on which any comprehensive summary should be based, have only in a few cases yet been carried out, and Buddhist enthusiasts in England have concentrated their attention on the Pali Canon to the neglect of other schools of the Hinayana and of the Mahayana.

To these inevitable difficulties there has been gratuitously added a further obstacle to the possibility of an intelligible view of the progress of Buddhist thought. Buddhism as a revealed religion demand faith from its votaries, and for sympathetic interpretation in some degree even from its students. But it is an excess of this quality to believe, on the faith of a Ceylonese tradition which cannot be proved older than A. D. 400, that the Buddhist Canon took final shape, even in its record of controversies which had arisen among the schools, at a Council held under the Emperor Asoka probably in the latter part of the third century B. C., a Council of which we have no other record, although the pious Emperor has recorded with infinite complacency matters of comparative unimportance. To credulity of this kind it is of negligible importance. To credulity of this kind it is of negligible importance that the Canon is written in an artificial literary language which is patently later than Asoka, or that the absurdity of the position has been repeatedly demonstrated.

Yet another, and perhaps more serious, defect in the most popular of current expositions of Buddhism is the determination to modernize, to show that early in Buddhist thought we find fully appreciated ideas which have only slowly and laboriously been elaborated in Europe, and are normally regarded as the particular achievement of modern philosophy. Now there is nothing more interesting or legitimate than, on the basis of a careful investigation of any ancient philosophy, to mark in what measure it attains conceptions familiar in modern thought; but it is a very different thing to distort early ideas in order to bring them up to date, and the futility of the process may be realized when it is remembered that every generation which yields to the temptation will succeed in finding its own conceptions foreshadowed. Truth compels us to admit that the adherents of Buddhism were intent, like their master, on salvation, and that their philosophical conceptions lacked both system and maturity, a fact historically reflected in the Negativism of the Mahayana. But instead of a frank recognition of these facts-of which Buddhism has no cause to be ashamed, for man seeks salvation rather than philosophical insight-we have interpretations offered to us as representing the true views of Buddhism, which import into it wholesale the conceptions of rationalism, of psychology without a soul, of Kant, of Schopenhauer, von Hartmann, Bertrand Russell, Bergson, et hoc genus omne. We are assured that Buddhism was from the first a system of subjective idealism, although history plainly show that such a conception slowly came into being and took shape in the Vijnanavada school which assails the realism of the more orthodox; we are equally assured that space was an ideal construction in the Buddhist view, though even in mediaeval Ceylon and Burma there is not a trace of the view, and it frankly contradicts the Canon and all the texts based upon it.

It is easy to understand this attitude as a reaction against the still practically complete failure of western philosophers to realize that, if they claim to be students of the history of thought-as a priori they should be-they have omitted a substantial part of their duty, if they do not make themselves reasonably familiar with the main outlines of Indian philosophy. But it is unphilosophical to exaggerate or distort, even in a just cause. Indian philosophy has merits of its own far from negligible, which are merely obscured by attempts to parallel the Dialogues of the Buddha with those of Plato, and the undeserved neglect which it has suffered in the west is largely excusable by the unattractive form in which Indian ideas are too often clothed.

My chief obligations, which I most gratefully acknowledge, are to the writings of the late Professor Hermann Oldenberg and of Professor de la Vallee Poussin; of others mention is due to Professor and Mrs. Rhys Davids for the admirable translations which more than redeem the defects of the texts issued by the Pali Text Society, and to Professors Beckh, Franke, Geiger, Kern, Oltramare, Stcherbatskoi, and Walleser. To my wife I am indebted for both criticism and assistance.

A. BERRIEDALE KEITH

EDINBURGH,

July, 1922.

| | ||

| PAGE | ||

| I. THE PERSONALITY AND DOCTRINES OF THE BUDDH | 13 | |

| 1. The Problem and the Sources | 13 | |

| 2. The Conclusions Attainable | 25 | |

| II. THE SOURCES AND LIMITS OF KNOWLEDGE | 33 | |

| 1. Authority, Intuition, and Reason | 33 | |

| 2. Agnosticism | 39 | |

| III. THE FUNDAMENTAL CHARACTER OF BEING | 47 | |

| 1. Idealism, Negativism, or Realism | 47 | |

| 2. The Impermanence and Misery of Existence | 56 | |

| 3. The Absolute and Nirvana | 61 | |

| 4. The Conception of Dhamma or the Norm | 68 | |

| IV. THE PHILOSOPHY OF SPIRIT AND NATURE | 75 | |

| 1. The Negation of the Self | 75 | |

| 2. Personalist Doctrines | 81 | |

| 3. The Empirical Self and the Process of Consciousness | 84 | |

| 4. Matter and Spirit in the Universe | 92 | |

| V. THE DOCTRINE OF CAUSATION AND THE ACT | 96 | |

| 1. Causation | 96 | |

| 2. The Development of the Chain of Causation | 97 | |

| 3. The Links of the Chain | 99 | |

| 4. The Interpretation of the Chain | 105 | |

| 5. The Significance of the Chain | 109 | |

| 6. The Breaking of the Chain | 111 | |

| 7. Causation in Nature | 112 | |

| 8. The Doctrine of the Act | 113 | |

| VI. THE PATH OF SALVATION, THE SAINT, AND THE BUDDHA | 115 | |

| 1. The Path of Salvation | 115 | |

| 2. The Forms of Meditation | 122 | |

| 3. Intuition and Nirvana | 128 | |

| 4. The Saint and the Buddha | 130 | |

| VII. THE PLACE OF BUDDHISM IN EARLY INDIAN THOUGHT | 135 | |

| 1. Early Indian Materialism, Fatalism, and Agnosticism | 135 | |

| 2. Buddhism and the Beginnings of the Samkhya | 138 | |

| 3. Buddhism and Yoga | 143 | |

| 4. The Original Element in Buddhism | 146 | |

| | ||

| VIII. THE SCHOOLS OF THE HINAYANA | 148 | |

| 1. The Traditional Lists | 148 | |

| 2. The Vibhajyavadins | 152 | |

| 3. Sarvastivadins, Vaibhasikas, and Sautrantikas | 153 | |

| 4. Precursors of the Mahayana | 156 | |

| IX. THE DOCTRINE OF REALITY | 160 | |

| 1. Realism | 160 | |

| 2. The Nature of Time and Space | 163 | |

| 3. The Ego as a Series | 169 | |

| 4. The Doctrine of Causation | 176 | |

| 5. The Chain of Causation, Internal and External | 179 | |

| 6. The Later Doctrine of Momentariness and Causal Efficiency | 181 | |

| 7. Vedanta Criticism of Realism | 184 | |

| X. THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CONSCIOUSNESS | 187 | |

| 1. The Abhidhamma Pitaka | 187 | |

| 2. The Milindapanha | 191 | |

| 3. Buddhaghosa and the Sarvastivadin Schools | 195 | |

| 4. The Classifications of Phenomena | 200 | |

| XI. THE THEORY OF ACTION AND BUDDHOLOGY | 203 | |

| 1. The Mechanism of the Act | 203 | |

| 2. The Mode of Transmigration | 207 | |

| 3. The Nature of the Buddha | 208 | |

| 4. The Perfections of the Saint | 212 | |

| 5. Nirvana as the Unconditioned | 214 | |

| | ||

| XII. MAHAYANA ORIGINS AND AUTHORITIES | 216 | |

| 1. The Origin of the Mahayana | 216 | |

| 2. The Literature | 222 | |

| XIII. THE NEGATIVISM OF THE MADHYAMAKA | 235 | |

| 1. The Doctrine of Knowledge | 235 | |

| 2. The Doctrine of Negativism and the Void | 237 | |

| XIV. THE IDEALISTIC NEGATIVISM OF THE VIJNANAVADA | 242 | |

| 1. The Doctrine of Knowledge | 242 | |

| 2. Idealism and the Void | 244 | |

| XV. THE DOCTRINE OF THE ABSOLUTE IN BUDDHISM AND THE VEDANTA | 252 | |

| 1. Suchness as the Absolute | 252 | |

| 2. Cosmic and Individual Consciousness | 256 | |

| 3. Nirvana as the Absolute | 257 | |

| 4. The Pre-eminence of the Mahayana | 259 | |

| 5. Vedanta and Mahayana | 260 | |

| XVI. THE BUDDHIST TRIKAYA | 267 | |

| 1. The Dharmakaya, Body of the Law | 267 | |

| 2. The Sambhogakaya, Pody of Bliss | 269 | |

| 3. The Nirmanakaya, Magic Body | 271 | |

| XVII. THE DOCTRINE OF SALVATION, BODHISATTVAS, AND BUDDHAS | 273 | |

| 1. The Problem of Salvation | 273 | |

| 2. The Equipment of Knowledge | 275 | |

| 3. The Equipment of Merit | 277 | |

| 4. The Virtue of Generosity or Compassion | 279 | |

| 5. Devotion and the Transfer of Merit | 283 | |

| 6. The Doctrine of the Act and the Causal Series | 286 | |

| 7. The Career of the Bodhisattva | 287 | |

| 8. Defects of the New Ideal | 295 | |

| 9. The Buddhas | 298 | |

| | ||

| XVIII. THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF BUDDHIST LOGIC | 303 | |

| 1. Logic in the Hinayana | 303 | |

| 2. Dignaga | 305 | |

| 3. Dharmakirti's Doctrine of Perception and Knowledge | 308 | |

| 4. Dharmakirti's Doctrine of inference | 311 | |

| 5. Controversies with the Nyaya | 313 | |

| ENGLISH INDEX | 320 | |

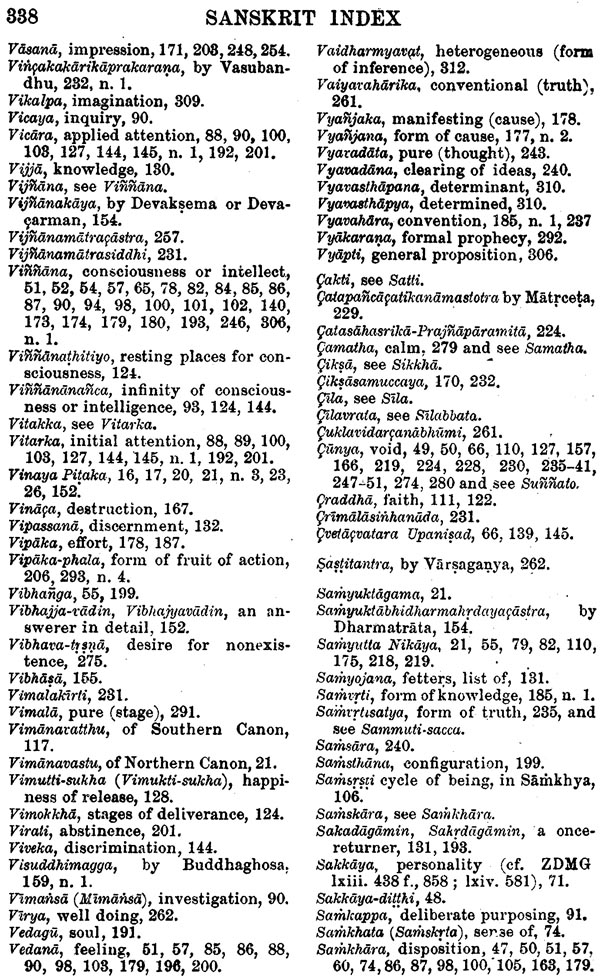

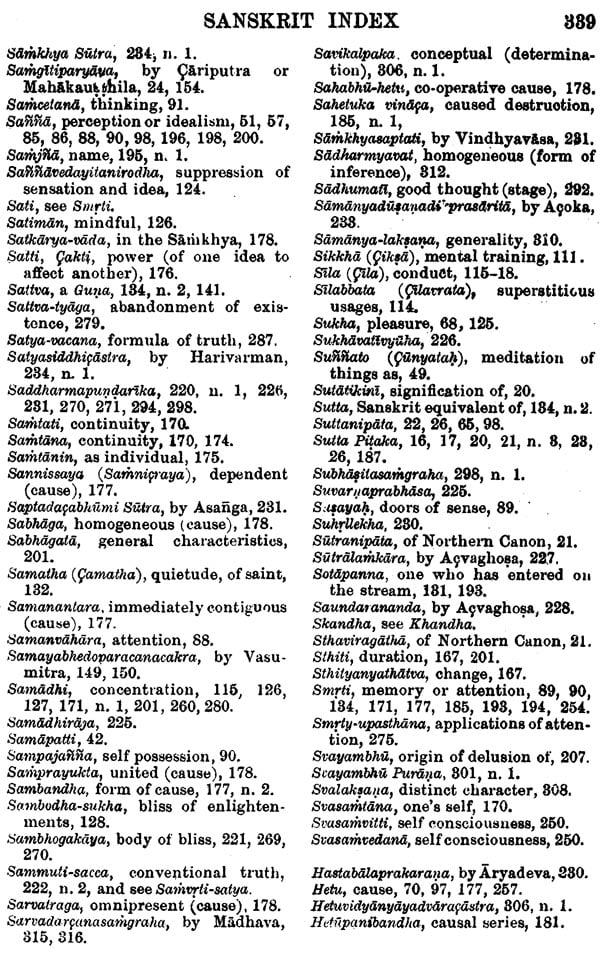

| SANSKRIT INDEX | 332 | |