An Empire of Books: The Naval Kishore Press and the Diffusion of the Printed Word in Colonial India

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG876 |

| Author: | Ulrike Stark |

| Publisher: | Permanent Black |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9788178242613 |

| Pages: | 606 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 580 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

The history of the book and the commercialization of print in the nineteenth century remain largely uncharted areas in South Asia. This monumental work on the legendary Naval Kishore Press of Lucknow, which was established in 1858, analyses an Indian publisher’s engagement in the field of cultural production.

Describing early centres and pioneers of print in North India, the author traces the coming of the book in Hindi and Urdu, She analyses the production of scholarly and popular books against a backdrop of cultural social, and economic developments, identifying the contributions of writers and literary people associated with the press. The detail, rigour, and sweep of this work brings nineteenth-century publishing in India to life in a manner hitherto unknown.

About the Author

Clrike Stark is Senior Assistant Professor at the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Chicago. She has earlier taught at Heidelberg University

Introduction

The history of the book in India is a history largely untold. This study is an attempt to shed light on the social, cultural, and material aspects of book production in nineteenth-century North India. During this transitional period in Indian history, a new institution arose in the urban literary-cultural sphere; signalling the triumph of print: the commercial publishing house. Through a case study of the Naval Kishore Press of Lucknow (est. 1858), the largest Indian-owned printing press and publishing house in the subcontinent at the time, this study investigates the impact of the commercial book trade on the diffusion and laicization of knowledge, and on processes of intellectual formation, modernization, and cultural renaissance in North India. More specifically, it explores the role of a singularly influential and prolific publisher in the production, transmission, and canonization of printed texts in the North Indian languages of Hindi and Urdu during a decisive moment in their shared and divided history.

In focusing on an Indian publishing house, this study enters a fascinating world of artisanal, scholarly, literary, and entrepreneurial talent. Book printing and publishing in nineteenth-century India was a venture as much entrepreneurial as intellectual. I trace a history which’ starts from the rise of the Naval Kishore Press and concludes with its position as the most successful business enterprise in nineteenth-century Indian publishing. In doing this, I am as interested in the economics of book production as in what has been called the human face of the book trade (lsaac/McKay 1999). Print generated new professions and introduced a distinctive figure into the colonial public sphere: the commercial printer- publisher. This book aims to show, through a famous example, that the foremost pioneers in Indian commercial publishing were not just savvy businessmen. Rather, they were men deeply engaged in the intellectual and literary life of their time who shared its larger cultural, cognitive, and social concerns. The more successful among them combined learning, cultural expertise, and antiquarian interests with craftsmanship and a keen sense of business. Exercising the various roles of entrepreneur, publicist, literary patron, philanthropist, disseminator of knowledge, and educator, the great icons of early Indian publishing-Fardunji Sorabji Marzban in Bombay, Munshi Harsukh Rai in Lahore, Maulvi ‘Abdul Rahman Khan in Kanpur, Mustafa Khan and Munshi Naval Kishore in Lucknow-assumed importance not only as early industrialists but also as intellectual pathbreakers and intermediaries. In investigating the life and career of one of them, I seek to explore the motivation of such men generally-people for whom printing and publishing was not just a business but a vocation.

The policy, success, and impact of the Naval Kishore Press (hereafter NKP) are inextricably linked to its founder-proprietor, whose multifaceted life presents an extraordinary tale of fortune. Munshi Naval Kishore (1836-95), the central character of this book, set out as a journalist and printer; his fame, however, rests on his achievement in both general and scholarly publishing. To narrate his life is to narrate the story of an Indian Hindu who participated in the revival of Hindu traditions while acting as one of the foremost promoters of Islamic learning and preservers of the Arabic and Indo-Persian literary heritage in the subcontinent. Naval Kishore belonged to the North Indian service gentry. He embodied the synthesis of Indo-Muslim and Hindu learned traditions in an exemplary fashion-most poignantly captured in Khvaja Abbas Ahmad’s succinct characterization of him as a ‘Muslim pandit and Hindu maulvi’. Yet Naval Kishore also belonged to the new generation of Indians who had received some Western education and been exposed to ideas of Western enlightenment rationality. Underlying his self-perception was a strong sense of the publisher’s cultural mission in society. This was to shape the policy of his firm in such a way that it combined capitalist principles of profit making and increasing turnover with literary and cultural patronage. This policy accounted for the development of the NKP as a vibrant intellectual meeting place, where scholars and literati of various backgrounds would gather and interact.

It is the dual nature of the publishing house-as a modem, capital-oriented industrial enterprise and an important site of intellectual, literary, and scholastic pursuits-which this books seeks to explore. Book publishing at the NKP-whether in Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Hindi, or Urdu-was never inspired by the profit motive alone. Rather, it was in- formed by the twin objectives of revitalizing India’s cultural and literary heritage and of contributing to Indian modernity through the diffusion of knowledge and education. Combining commercial with educative, scholastic, and aesthetic aims, such a policy followed the imperatives of cultivation and entertainment; it included literature both ‘high’ and ‘low’ and sought to address the scholarly elite and the general reading public alike. How these objectives were achieved will form a major concern of my book.

Through an investigation of the internal structures and external relationships of the publishing house, I attempt to reconstruct the process by which the ‘House of Naval Kishore’ set about creating a distinct identity for itself. The period under review spans the years from 1858 to 1895. The first date marks the establishment of the firm, which, conveniently enough, coincides with a transformative moment in Indian history. The second date marks the death of Naval Kishore, which brought to a close a major phase in the history of the publishing house.

While drawing inspiration from the genre in which much publishing history is written, this book is only in part a conventional ‘house history’, for it also seeks to address larger questions of the transformations in literary culture and learned practice induced by commercial printing. Often cited, a comment made by the Urdu cultural historian Abdul Halim Sharar in his famous swan song of Lakhnavi culture Lucknow: The Last Phase of an Oriental Culture still remains one of most poignant formulations of the vast and lasting impact of the NKP on the North Indian literary and cognitive domain: ‘The Newal Kishore Press is still the key to the literary trade. Without using it no one can enter the world ofleaming’ (Sharar 1975: 108).

With its focus on the second half of the nineteenth century, this book is not a study of the shift from oral to written culture.? Nor is it primarily concerned with the transition from manuscript or scribal culture to print culture initiated in Hindi and Urdu at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Instead, it addresses a third paradigm shift in the history of print in India, which I call the ‘commercialization’ of print. The term ‘commercialization’, as used here, refers to a number of parallel and interconnected pro- cesses that shaped the regional-language book trade from around the 1840s: the introduction of new reproduction techniques and the ensuing shift to industrialized mass production; the decline in production costs and the concomitant possibility of reduction in book prices; the transition from European to large-scale Indian ownership, agency, and investment in the book trade; the rise of the marketplace as a dominant force in literary culture; the emergence of commercial genres; and, finally, the creation of a new class of professional authors. In short, commercialization describes the transformation of the printed text from artefact and cultural asset into a cheap and easily available consumer commodity. As such, it is intimately linked to wider economic, social, and cultural shifts induced by colonialism-notably, the dawning of the age of industrial capitalism, the spread of colonial literacy and formal education, and the rise and economic empowerment of an Indian educated middle class.

Contents

| Acknowledgements | x | |

| Note on Transliteration and Conventions | xiii | |

| Tables | xv | |

| Illustrations | xvi | |

| Glossary | xvii | |

| Abbreviations | xix | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| Preparing the Ground: Towards a History of the Book in India | 4 | |

| The Publishing House and the Literary System | 9 | |

| Literacy, Readership, and Consumption | 12 | |

| Indigenous Responses to Print | 21 | |

| Publishers and the Colonial State | 23 | |

| 1 | The coming of the book in hindi and urdu | 29 |

| 1.1 | Early Printing in Hindi and Urdu | 35 |

| 1.2 | The Impact of Lithography | 45 |

| 1.3 | Printing in the NWP & Oudh Before 1857: Three Centres | 49 |

| 1.4 | The Age of Commercialization | 64 |

| 1.5 | Control versus Encouragement: Publishing under Colonial Legislation | 83 |

| 2 | A life in print: munshi naval kishore (1836-1895) | 107 |

| 2.1 | Family Background, Education, and Apprenticeship | 110 |

| 2.2 | Setting up Business in Lucknow | 124 |

| 2.3 | he Public Life of an Indian Publisher | 129 |

| 2.4 | The Publisher as Politician: Naval Kishore and the Anti-Congress Movement | 151 |

| 3 | An Indian success story: the house of a v al kishore | 164 |

| 3.1 | The Early Years (1858-1865) | 165 |

| 3.2 | The Phase of Expansion (1865-1892) | 170 |

| 3.3 | Printing Books: Traditional Craftsmanship and Modem Technology | 184 |

| 3.4 | Marketing Books: Strategies of Advertising and Diffusion | 194 |

| 3.5 | Author-Publisher Relations | 205 |

| 3.6 | The Naval Kishore Press After 1895 | 220 |

| 4 | The colonial factor: patronage, collaboration, and money matters | 225 |

| 4.1 | Textualizing Mass Education: The Textbook Venture | 228 |

| 4.2 | Copyright Controversies | 240 |

| 4.3 | Money Matters | 250 |

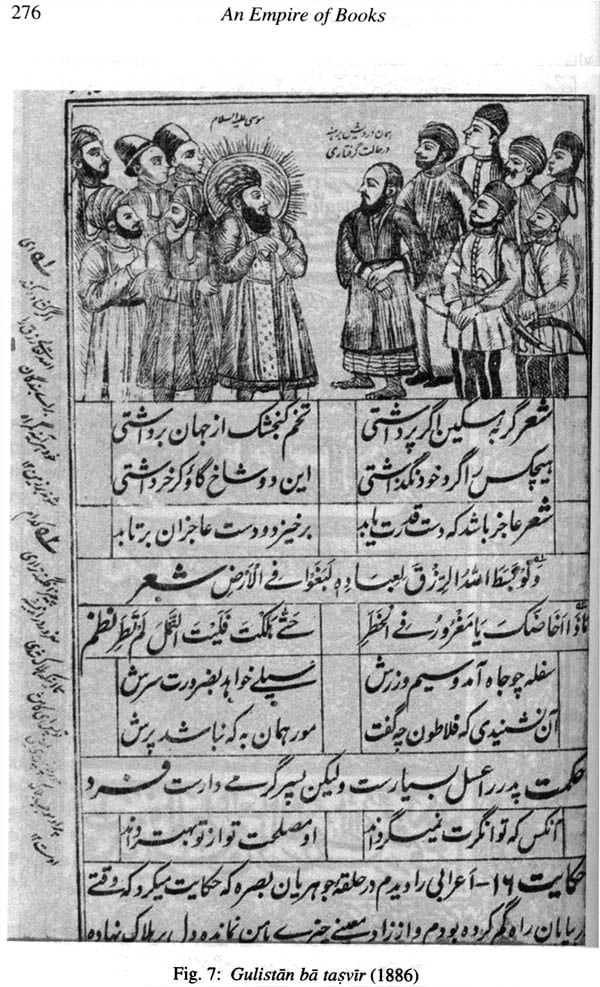

| 5 | Calligraphers, scholars, and translators: the publishing house as an intellectual space | 266 |

| 5.1 | The Department of Copying and Calligraphy | 268 |

| 5.2 | The Department of Composition and Translation | 280 |

| 5.3 | Medicine and History for Lay and Scholarly Readers | 291 |

| 5.4 | A Transition in Print: From Persian to Urdu | 306 |

| 5.5 | Sanskrit Shastric Texts for the Modem Reader | 314 |

| 5.6 | Selective Encounters with the West: Translating English Works | 332 |

| 5.7 | Coping with Multilinguality: Dictionaries and | |

| 5.1 | Vocabularies | 341 |

| 6 | Avadh akhbar: politics, public opinion, and the promotion of urdu literature | 351 |

| 6.1 | From Weekly to Daily: The Making of an Urdu Newspaper | 354 |

| 6.2 | Contents and Policy | 364 |

| 6.3 | Promoting Urdu Literature: Editors and Contributors | 371 |

| 6.4 | Other Journalistic Ventures | 381 |

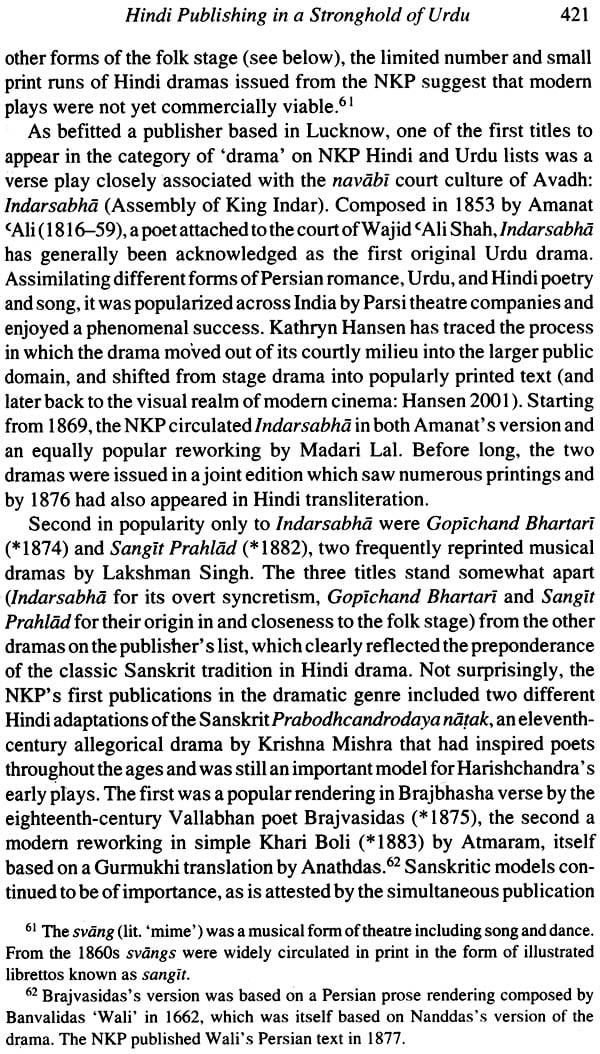

| 7 | Hindi publishing in a stronghold of urdu | 385 |

| 7.1 | Popularizing the Classics of Hindu Devotional Literature | 391 |

| 7.2 | Expanding the Horizons of Poetry | 402 |

| 7.3 | Commercializing Hindu Science | 406 |

| 7.4 | New Genres and a New Historical Perspective | 413 |

| 7.5 | Against the Divide: Patterns of Hindi and Urdu | |

| Publishing | 429 | |

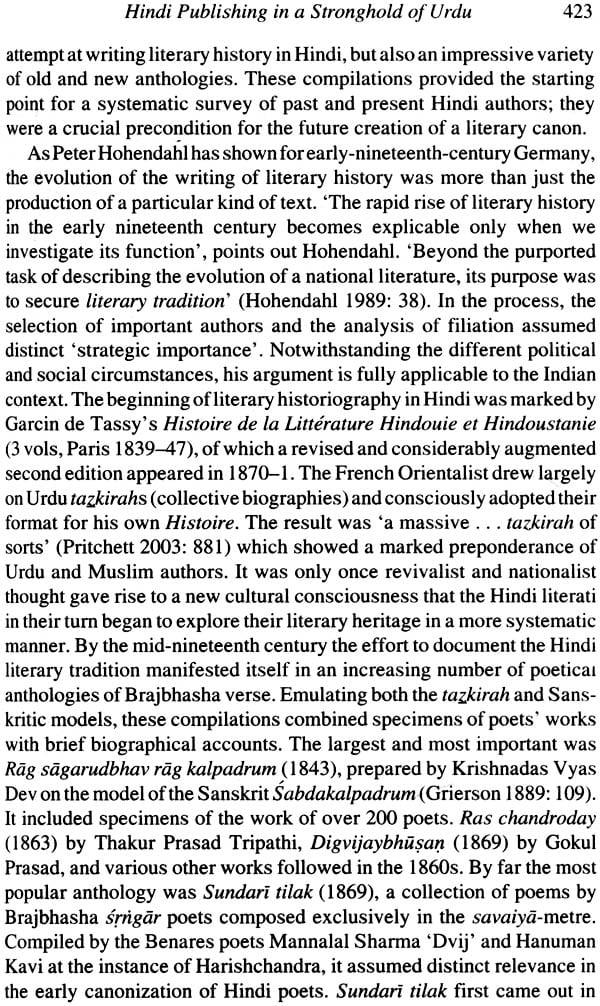

| Conclusion | 445 | |

| Appendices | 453-531 | |

| Bibliography | 532 | |

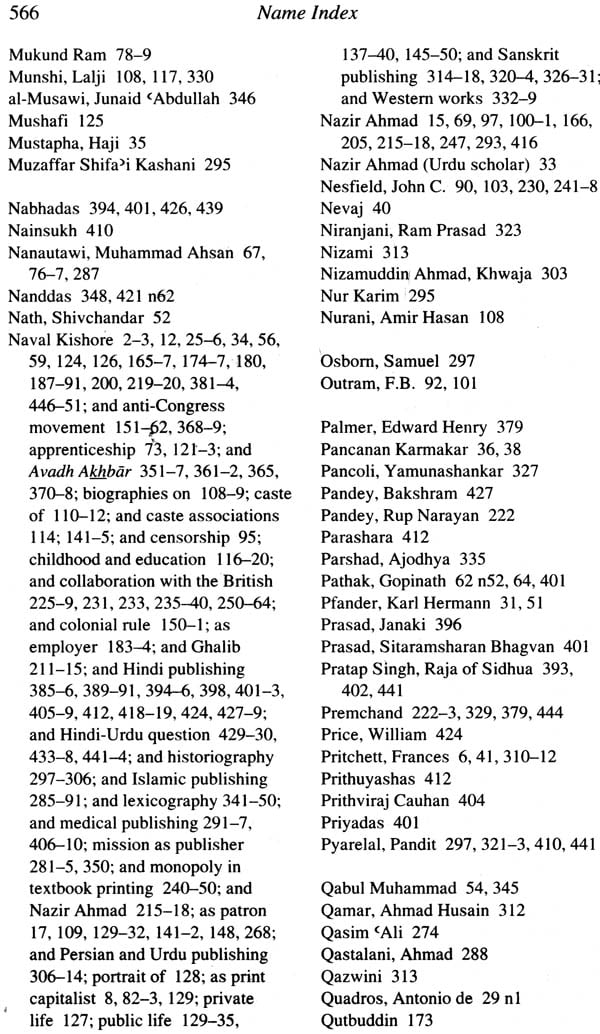

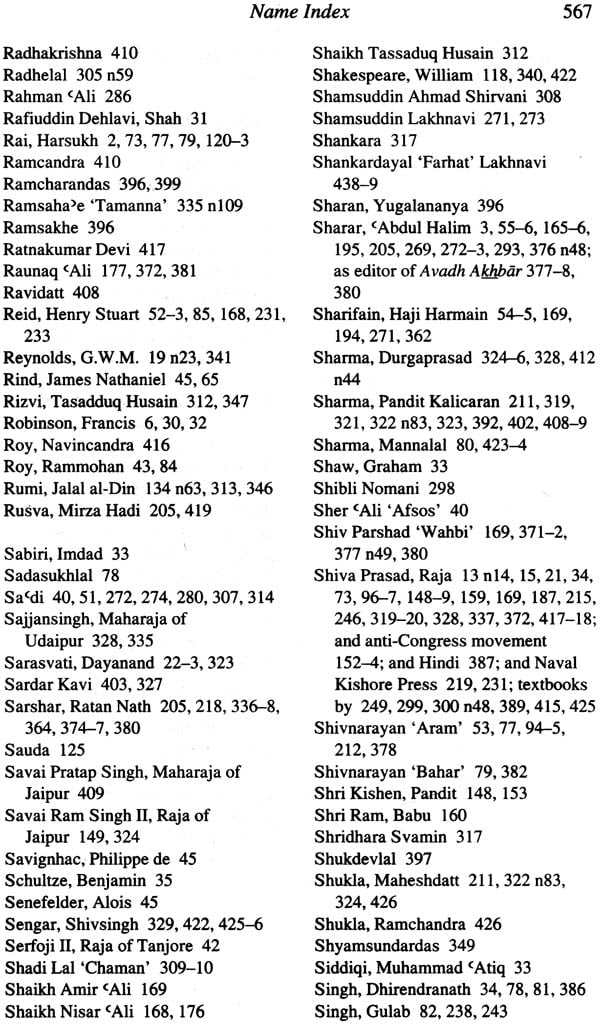

| Index | 561 |