Uttankita Sanskrit Vidya-Aranya Epigraphs (Vidyaranya) - An Old and Rare Book

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAO621 |

| Publisher: | Bharatiy Vidya Bhavan |

| Language: | Sanskrit Text with English Translations |

| Edition: | 1985 |

| Pages: | 175 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.0 inch X 5.0 inch |

| Weight | 230 gm |

Book Description

The heyday of the celebrated Mogul Empire in India was, from Babur to Auranqazebe, about 181 years from 1526 to1707 A.D.

The heyday of the celebrated British reign over India was for 190 years from 1757 (the Battle of Plessey) to 1947 A.D.

The comparable time-span of the less well- known but splendorous Vijayanagar Empire exceeded those of the Moguls and the British regimes in India. Its spiritual founder-and the preceptor of its first three Emperors –was VIDYARANYA, great as sage, great as writer and great as statesman, about whom this Volume deals.

SECTION 1 : THE UTTANKITA SANSKRIT VIDYA-ARANYA TRUST

The name “UTTANKITA VIDYA ARANYA” means in Sanskrit “The Forest of Sculpted Knowledge”. As the name itself indicates, the Trust, to which His Holiness Jogadguru Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati Sankaracharya Swamigal of Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Pitha has endowed this name, seeks, with His Blessings, to delve into, and publish, in a codified manner as many as possible of the important Sanskrit epigraphic records of India and of her culture as may be presently available within India and abroad, and which, in substantial part, are found inscribed on stone tablets, copper plates and the like. Indeed, this efforts by the Trust has been inspired by the deep and abiding interest and concern of His Holiness in preserving, for India and for the world, the rich and profound culture heritage of the land and its people.

Importance of India Epigraphy It is well- known that in ancient India (unlike in China and in other civilizations to the west of India) there was no systematic attempt to maintain chronicles of history in the commonly understood meaning of the term. As the Trust’s Chairman Dr. D.C. Sircar has put it, “Ancient India did not produce a Herodotus, Thucydides or Tacitus to leave for posterity a genuine and comprehensive history of the achievements of her sons. Therefore, the information gathered from various sources, such as the literary, epigraphic, numismatic, archaeological and monumental records, has to be utilized to reconstruct this lost history of the most glorious days of India. Of all such sources for the reconstruction of early Indian history, epigraphic records are the most important, for they provide material for the major part of what we now know about the achievements of the Indians of old”.

“No doubt Indian (has) contributed to the civilization of the world in all periods of history; but her more significant contributions to world culture were made in the early period”.

With the emergence of India into independence and with her taking her rightful place in the comity of Nation, when she is endeavoring to adopt modern methods of material progress without compromising her ancient heritage (a heritage which has outlasted countless invasions and centuries of alien rule), it is but right that all avenues which reveal her past be made open not only to her sons and daughters of this, and of coming, generations but also to the world at large.

The merits of epigraphical evidence about India’s past are undeniable. The following are among the major merits of such evidence.

**The great importance of inscriptions lies in the fact that they generally offer information about personages and events of history about which nothing (or little) may be known from other sources. The pillar inscription at Allahabad of Emperor Samudragupta of the Gupta dynasty (mid 4th century A.D.) and the Aihole Jaina Temple inscription of King Pulikesin II (first half of 7th century A.D.) of the Badami Chalukya dynasty may be cited as examples. The former records the “Digvijaya” (Triumphal progress) of Emperor Saamudragupta which is not known from other sources, besides making mention of a number of places and of a number of rulers whom he subdued. The Aihole inscription contains the earliest reference to the famous Sanskrit poets Kalidasa and Bharavi. Similarly a 9th century inscription from Kampuchea (Cambodia) refers to one Siva Soma who is stated to have been a disciple of the Great Sankaracharya of whom more will be said later on herein.

**Epigraphy serves as valuable evidence with which to evaluated historical accounts basda on traditions. This is well known and needs no illustration.

**Among the merits of India epigraphy as sources material for history the foremost is the fact that the authors in most cases described contemporary events or events in the near past within living memory or based on reliable evidence available to them. An interesting example of this type of records is the Talagunda inscription of the Kadamba dynasty (5th century A.D.).According to it, a boy named Mayurasarman from a place near Banavasi went to Kanchi (one of the celebrated centers of learning against Pallava authority, subdued several warriors and established the Kadanba dynasty in the Banavasi region of Karnataka in South India.

Epigraphs are generally free from variant reading as they were not usually liable to modification like literary works that were copied and recopied from time to time. Each epigraph is recorded on stone etc., once for all, whereas literary works have undergone copying and recopying, with changes from time at the hands of the copyists.

**An important feature of epigraphic evidence is that many of the knotty problems of early Indian chronology have been solved by inscriptions dated in eras, or mentioning past events with reference to particular dates, or containing a record of events in chronological order, etc. The inscription at Junagarh (Gujarat) of Rudradaman (150 A.D.), the inscriptions at Badami (Karnataka) of Pallava King Narasimhavarman I (mid-7th Century A.D.) and the early Pandya inscription found in the rock-cut cave temple at Triuparankundram near Maduri in Tamilnadu are examples.

*The contents and forms of epigraphs, particularly those on copper-plates, are in accordance with norms set forth in respective codes (the Dharma Sastra and the Artha Sastras); some records are actually seen to incorporate the parlance of such codes or sastra, as for instance the inscription in the rock-cut cave temple at Tiruchirapalli of the time of Pallava King Mahenravarman I (first half of 7th century A.D.).

**The text of several inscriptions are examples of exquisite prose and poetry, whose authors, when mentioned in the inscriptions, are known from no other sources. The Junagarh rock inscription of Rudradaman (mid 2nd Century A.D.) furnishes a good example of prose; the text of the Talagunda inscription of the Kadamba dynasty is a beautiful specimen of poetry. Hariena (the poet of the Allahabad pillar inscription of Emperor Samudragupta) and Ravikirtti (the composer of the Aihole Jain Temple inscription of the time of Pulikcain II) are poets whose works have not yet come to light elsewhere.

The importance of epigraphic and similar material as sources of authentic knowledge about ancient India as also the fact that research into epigraphy has to be regarded as continuous (and not closed at any point of time) can be seen from the following telling illustration.

| Publisher's Note | vii | |

| PART-I | INTRODUCTION | |

| Section : | ||

| 1 | The Uttankita Sanskrit Vidya Aranya Trust | 3 |

| 2 | Vijayanagara and Vidyaranya | 15 |

| 3 | General Information of Contents | 26 |

| 4 | Diacritical Notations | 29 |

| PART-II | THE INSCRIPTIONS | |

| Chapter : | ||

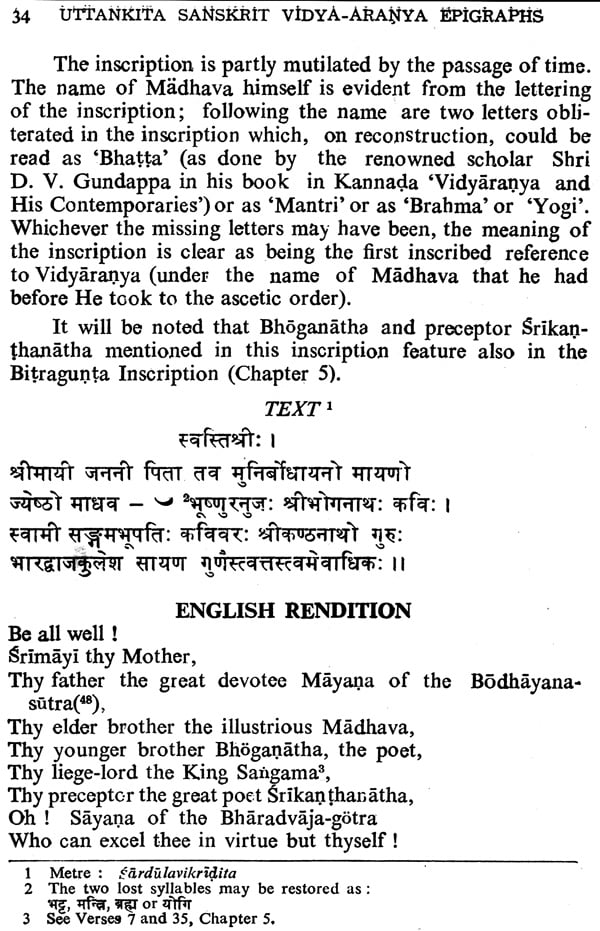

| 1 | The Kanchipuram Inscription | 33 |

| 2 | The Bestarahalli and Kapaluru Grants | 35 |

| 3 | The Mudiyanur Copper Plates | 60 |

| 4 | The Sringeri Inscription of 1346 A.D. | 69 |

| 5 | The Bitragunta Copper Plates | 74 |

| 6 | The Kudupu Stone Inscription | 84 |

| 7 | The Nagalapura Stone Inscription of 1377 A.D. | 87 |

| 8 | The Bhandigadi Visvesvara Temple Inscription | 91 |

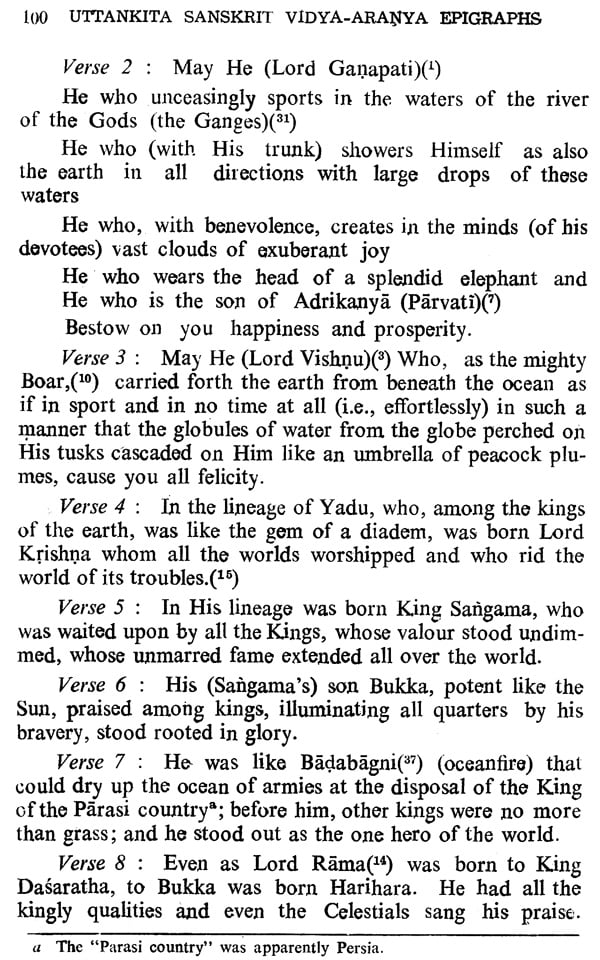

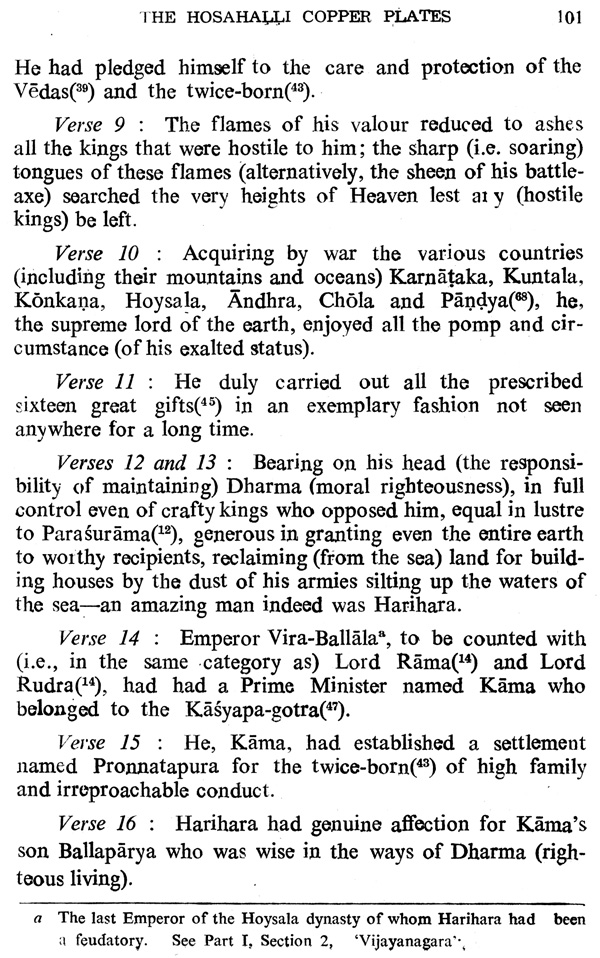

| 9 | The Hosahalli Copper Plates | 95 |

| 10 | The Belagula Copper Plates | 104 |

| 11 | The Paschimavahini Inscription | 110 |

| 12 | The Sringeri Plates of Harihara II | 112 |

| 13 | The Chantar Inscription | 118 |

| 14 | The Srirangam Inscription | 121 |

| 15 | The Hireguntanuru Stone Inscription | 125 |

| 16 | The Nalkudure Copper Plates | 128 |

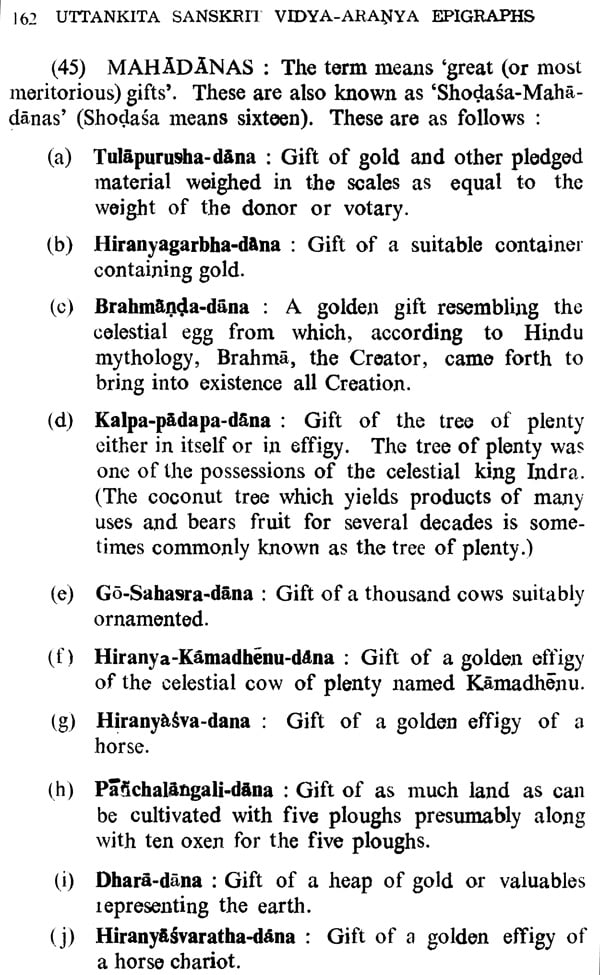

| PART III : | EXPLANATORY NOTES | 135 |

| Appendix I : | Metres used in the Sanskrit Texts of the Inscriptions in Part II | 169 |

| Appendix II : | Abbreviations used in Footnotes on Texts and in Appendix III | 170 |

| Appendix III : | Table of Inscriptions with their "Findspots" | 171 |

| | ||

| 1 | The Paschimavahini Inscription | |

| 2 | The Srirangam Inscription. |