India and The Raj 1919- 1947

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NBZ852 |

| Author: | Suniti Kumar Ghosh |

| Publisher: | Sahitya Samsad |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2019 |

| ISBN: | 9788179551141 |

| Pages: | 734 |

| Cover: | HRADCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 6.30 inches |

| Weight | 1.14 kg |

Book Description

Which classes did the Congress leadership represent before 1947? What were their goals and forms and methods of struggle? What were the objects of the seemingly anti-imperialist movements they occasionally initiated? And where did they lead to – freedom or more sophisticated bondage than direct colonial relationship? Relying mainly on primary, while not neglecting secondary, sources, this book seeks to find out answers to these and related questions. The answers are wholly contrary to the basic assumption with which conventional historiography begins. While exposing what was India's shame, India and the Raj 1919-1947 also deals briefly with the glorious aspects of India's anti-colonial struggle – the struggles waged by the peasantry, the working class and the urban petty bourgeoisie. These struggles, genuinely antiimperialist, and the movements launched by the Congress leadership, were not complementary, as in generally assumed, but essentially of an antagonistic character. In the absence of a mature revolutionary party these struggles failed to merge in a broad stream powerful enough to sweep away imperialist domination and its domestic props.

Suniti Kumar Ghosh had his M.A. degree in English in 1939 from the Calcutta University. His dissertation on Tennyson was published by the University. He served as college teacher for many years.

While a teacher at the Dinajpur College, he was closely associated with the Tebhaga struggle in 1946-7. Soon after it was over, he was offered membership of the CPI and he accepted it. He was externed from East Pakistan in 1949 for his political activities. After the Naxalbari upsurge in 1967 he joined the Communist Revolutionaries and became a member of the All India Co.. ordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries and afterwards, a member of Central Committee of the CPI(ML). He has written several books: The Indian Big Bourgeoisie (which has been translated into Malayalam, Tamil and Hindi); India and the Raj 1919-1947; Imperialism's Tightening Grip on Indian Agriculture; Development Planning in India (also translated into Hindi); The Himalayan Adventure: India-China War of 1962; The Tragic Partition of Bengal etc.

India and the Raj 1919-1947 : Glory, Shame and Bondage first appeared in two volumes; Vol. one (or Part I of this combined volume) on 1989 and Vol. two (or Part II) was published by the Research Unit for Political Economy of Mumbai in 1995. Vol. two went out of print several years ago.

Establishment historians (and people generally) hold as axiomatic truths that the Indian National Congress led the Indian people in the struggle for freedom, that M. K. Gandhi, the unchallenged leader of the Congress for about three decades, awakened the people from their slumber and fashioned the unique weapon of non-violent satyagraha which overthrew the rule of one of the mightiest imperialist powers of the world, and that thus emerged an independent, sovereign state – the Indian Union.

Like Jean Chesneaux, the French historian and author of Pasts and Futures or What is History for ? I believe that history and historians are not above class struggle. History is one of the most powerful tools in the hands of the ruling classes for moulding the consciousness of the people in order to maintain their rule. As Chesneaux put it, “our knowledge of the past is a dynamic factor in the development of society, a significant stake in the political and ideological struggles of today, a sharply contrasted area. What we know of the past can be of service to the Establishment or to the people's movement.” “The revision of official history", he said, “is regarded as one of the essential points of departure for the people's struggles.”

This book offers an interpretation of the history of the Gandhian era which is in sharp contradiction with that in Establishment history. Whether this interpretation is substantiated with facts and reason is for the readers to judge.

Brief references have been made in this book to the anti-colonial and other class struggles waged independently of the Congress (rather, in wiolation of the Congress leaders' sermons) by the working class, the peasantry and the petty bourgeoisie. It is those struggles which, though suppressed by the alien rulers and their Indian collaborators, form the glorious aspect of Indian history.

In this book there are many quotes from the Collected Works of MaThaima Gandhi, published by the Publications Division of the Government of India. I have taken most of them from the first edition, which comprises ninety volumes. Some quotes have been taken from other edition and these have been mentioned. But, I am afraid, some other quotes, too,

To understand any complex social phenomenon, we have to turn to a study of its history; and thus we must seek the roots of the condition of present-day India in our past.

This is precisely the approach of Sunity Kumar Ghosh's works The Indian Big Bourgeoisie: its Genesis, Growth and Character, India and the Raj: Glory, Shame and Bondage, and The Tragic Partition of Bengal. They offer an interpretation of pre-1947 India that stands in dramatic opposition to the overwhelming weight of established historiography.

The interpretation offered by these works has broadly been shared by a stream of political opinion in India for decades. But these works offer for the first time a wealth of substantiation and tightness of argument which makes it impossible for established historiography to dismiss. The thus constitute a landmark in modern Indian historiography.

The proponents of the established views have chosen neither to contend seriously with this newly substantiated interpretation, nor to budge even slightly in their own interpretation. Instead, they have done their best to ignore it, as if it did not exist.

It is important to realise that these decisions are not merely academic, but political. S.K. Ghosh's works are not based on newly-discovered archival material, but on material that has long been available, and indeed has been the object of study by established historians. Still the facts he cites strike one as revelations, because there has been a remarkable silence about them – no doubt, precisely because they have a profound political implication.

For if the Indian National Congress did not win genuine independence for India in 1947, we are as yet not free today, and every act of the Indian State must indeed be seen in that light.

It is all the more necessary for those seriously interested in the future of India to study this body of work. This fresh edition of India and the Raj is a welcome event, and needs to be widely promoted.

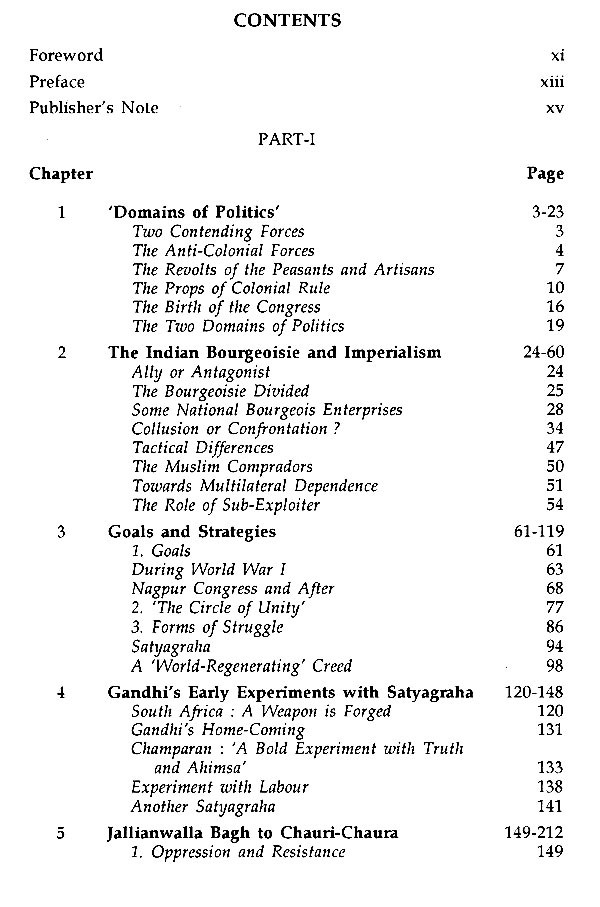

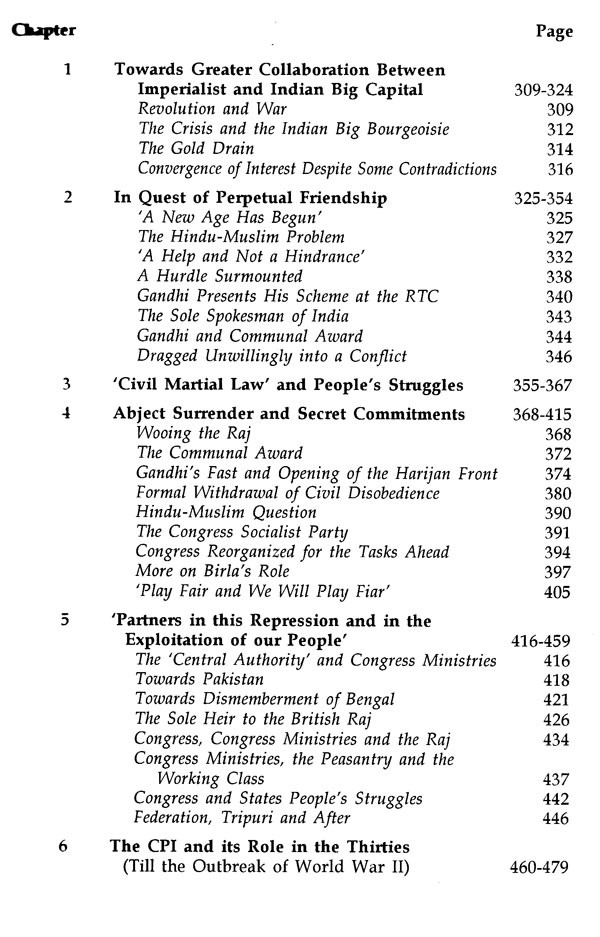

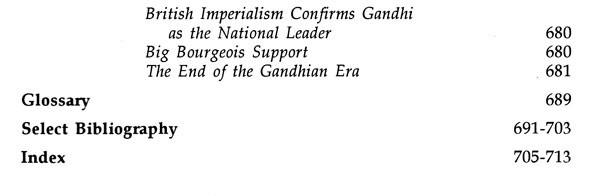

**Contents and Sample Pages**