New Age Hunger Games Warring Farmers and the Violence of Sustenance

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAC836 |

| Author: | Sujata Dutta Hazarika |

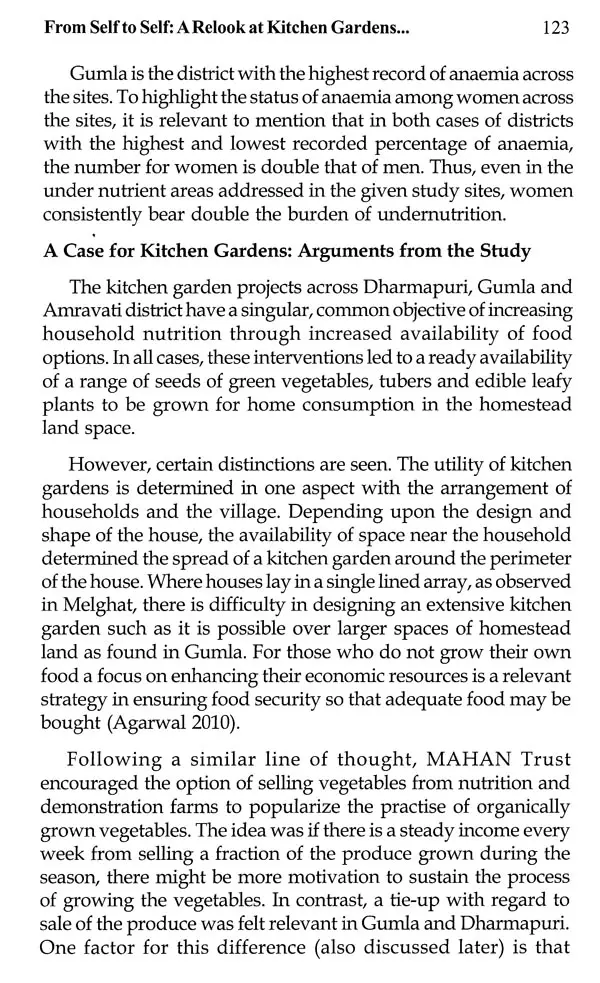

| Publisher: | Synergy Books India |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2020 |

| ISBN: | 9789382059868 |

| Pages: | 173 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 6.50 inch |

| Weight | 400 gm |

Book Description

August 14, 2016; once more, a violent story was reiterated: once more, a seething wound was recklessly taped by a quick fix cure; once more, a burning inferno was smothered by a helpless district administration's short-sighted attempt at arbitration for peace transaction. The clash between the expanding populace of Muslim settlers in Halaikunda char area (temporary sand plains formed by river Bharmaputra) with the local indigenous population in the Mayong area in the Darrang district of Assam, could be thankfully contained this time from exploding into large scale violence and ethnic conflict.

The riverine areas (island) of the river Brahmaputra, known as "Char/ Chapori" cover about 3.60 lakhs hectares of land with a population of approximately 24.90 lakhs (as per Socio Economic Survey 2002-03). Because of limited accessibility and administrative constraints, these remote areas are marginalized and under developed. While other similar districts marred with low development index have been declared as "Backward" for the purpose of providing special incentives to attract industries, for these districts, such concerns are limited. As a result, the char settlers, largely agriculturists belonging to the Muslim community, are subjected to discrimination and have a low human development index.

In 1998, a community of agriculturalists from Halaikunda char area, comprising of 70 erosion affected Muslim families from Katahguri char, was allowed to settle in this area by the local population on humanitarian grounds. Over the years, as the population of the immigrant community, who lived on land leased out by local land owners increased, the insecurity and clash over resources grew. The indigenous communities, also largely agrarian but Hindu in religion, felt threatened by the growing competition from these Muslim immigrants. The age old story of fixing scapegoats was once more reiterated within the general scenario of low human development, economic insecurity, poverty and competition over access to limited natural resources, like land and forest, ultimately resulting in an ethnic conflict, which has now become a recurring issue in Assam.

Overtly, it appears that the growing conflict is largely ethnic in nature, smeared by disparity of religious interests and economic underdevelopment. A decade of academic research and policies on peace initiatives in the region appear to be guided by this perspective. After all, North East India has had a history of intermittent ethnic conflict, insurgency and violence, for which different reasons, ranging from an apathetical post colonial policymaking, ethnic identity assertion, and finally development deficit in the overall social dynamics of the region, have been held responsible. Assam, the largest geographical area from where most of the other states were carved out as part of India's post independence development policy, has been a battleground of internal conflict since. With a much smaller land area now than what it was before independence, it has a history of violent conflict over land between the indigenous tribals and ethnic Bengali Muslim settlers dating back to 1952, with subsequent violent clashes occurring in 1979-1985, 1991-1994, and 2008. Before the 2016 riots, the most recent riots and violence between Bodos and Bangladeshi Muslims erupted in July 2012 in the BTAD districts of Kokhrajar, Chirang, and Dhubri. According to the Asian Centre for Human Rights, 77 people were killed and over 400,000 displaced from the violence, including both Bodos and Bangladeshi Muslims. Experts on the growing conflict in the region contended that the riots were the result of Bodo resentment against Bangladeshi immigration and the consequent loss of land and cultural identity. The effects in the aftermath of the riots, saw large scale protests across the northeast demanding "early detection and deportation" of illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. The Bodos then joined other indigenous tribal communities in Assam to collectively address the issue. According to India's National Cyber Investigation Agency, following the violence, students belonging to the North East living in other parts of India, received threats from a radical Muslim organization known as the Popular Front of India (PFI). Moreover, Muslim groups organized violent protests in Mumbai in response to the Assam riots (and violence in Mynamar), and the all Bodoland Muslim Student's Union (ABMSU) threatened to declare jihad and holy war against the state.

Agriculture is man's oldest and among the most tested out sources of livelihood options. The growth of agricultural technology and innovations not only reflect man's creative potential but also his capacity for ingenuity and resilience in the face of the challenges that strike at the very root of his existence; hunger, sustenance and food security. The advancement of agricultural technology from an historical perspective has been rather paradoxical because the instruments of commercial agriculture adopted to address the fear of starvation, food security and generation of surplus, in reality, aggravated the crisis more severely. The very solutions that were reached to address the global challenge of food production by adopting technological means for scaling up production led to severe challenges that compromised quality and health, environment and wellbeing, equity and access to food and finally poverty, starvation, pollution and conflict.

There is scientific evidence to prove today that conventional agriculture contributes to about 20% of climate change issues such as anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, even more than the transport sector. The most significant emissions from agriculture are carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide which significantly contribute to global warming. There is also increasing evidence that it is possible for traditional agriculture to produce enough to feed a growing population through its biodynamic and agro-ecological structures. For example, in 2006, a seminal study in the Global South compared yields in 198 projects in 55 countries and found that ecologically attuned farming increased crop yields by an average of almost 80 percent. A 2007 University of Michigan global study concluded that organic farming could support the current human population, and expected increases without expanding farmed land. Then, in 2009, came a striking endorsement of ecological farming by fifty-nine governments and agencies, including the World Bank, in a report painstakingly prepared over four years by four hundred scientists urging support for "biological substitutes for industrial chemicals or fossil fuels."

It is now being argued more and more that the main reason industrial agriculture, with a top down agricultural policy cannot work to meet society's food requirement is because it is just another remnant of the systemic crisis that dominates our social worldview where society is seen as a combination of independent, dissociated parts and not of interacting symbiotic elements. In agriculture too, the same conceptualization is dominant and a perfectly dynamic living entity of interacting elements such as the soil, land, water, forest, farmers, producers, consumers, community, environment have all been reduced to a mechanized, commercial, economic enterprise bereft of and alienated from, human connections with nature, with community and more significantly, with the individual's own creative and inherent identity, with the 'self'.

Like every other aspect of contemporary society that challenges the worldview of sustainability in conventional capitalism, structures of industrial agriculture that forms the systemic foundation of food system fails to register and comprehend the impact of its inherent destructive practices on nature's regenerative process, and thus ends up devaluing its most vital and invaluable resource capital that forms its foundational premises such as community, nature, environment and individuals. Due to abnormal leaning towards commercial content, concentration of capital, lengthy supply chain, cosmetically blemished foods, and capacity to control market demand within the food system, industrial agriculture is ill equipped to address challenges of food security, hunger, health and social equality.

**Contents and Sample Pages**