Synthesis of Yoga

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAD325 |

| Author: | Kireet Joshi |

| Publisher: | Centre for Studies in Civilizations |

| Edition: | 2011 |

| ISBN: | 9788187586500 |

| Pages: | 998 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.5 inch x 8.5 inch |

| Weight | 2.85 kg |

Book Description

The volumes of the PROJECT ON THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE, PHILOSOSPHY AND CULTURE IN INDIAN CIVILIZATION aim at discovering the main aspects of India's heritage and present them in an interrelated way. In spite of their unitary look, these volumes recognize the difference between the areas of material civilization and those of ideational culture. The project is not being executed by a single group of thinkers and writers who are methodologically uniform or ideologically identical in their commitments. The Project is marked by what may be called 'methodological pluralism'. Inspire of its primarily historical character, this project, both in its conceptualization and execution, has been shaped by scholars drawn from different disciplines. It is for the first time that an endeavor of such a unique and comprehensive character has been undertaken to study critically a major world civilization.

The history of Indian yoga is a most fascinating chapter in the larger history of man's highest endeavours to exceed manhood and to hew new paths of evolving the next species. This volume concentrates on the theme of the synthesis of yoga, and dwells principally on five systems of the synthesis of yoga: the very first synthesis of yoga is to be found in the Vedic Samhit asked the earliest records of human civilization. This synthesis was followed by the synthesis that we find in the Upanisads. The yoga of the Gita, which comes next, is eminently the synthesis of the paths of knowledge, action and devotion. The fourth synthesis is to be found in the Tantra. The latest synthesis of yoga which draws from all previous systems of yoga, presents a new departure both in its objectives and methods. This is the synthesis of yoga of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, which has worked out, with scientific rig our the processes of ascent to the Super mind as also of the descent of the Super mind on the Earth,--the processes that are new and indispensable for the synthesis of Matter and Spirit and for the evolution of the Sacramental Divine Body, which will mark a revolutionary change in the very processes of evolution and establish a new mode of Sacramental action capable of creating on the Earth the fulfillment of the ideals of light, freedom, bliss and immortality. Science and spirituality meet in a natural synthesis in this yoga and it provides a solution to the contemporary evolutionary crisis. It is this theme that imparts to this volume its special relevance.

This volume, while laying due emphasis on the above mentioned five systems of synthesis, brings out subtleties and complexities of various other systems of yoga in an attempt to show how the tendency of synthesis is vividly present in them. In some respects, this volume revisits some of the areas that have been expanded in great detail in the earlier volumes on yoga that form part of PHISPC.

Pursuit of yoga is a living tradition in India, and it is this pursuit which provides to Indian culture its perennial spiritual essence. This volume while dwelling on the theme of the synthesis of yoga takes us to those realms of spiritual consciousness by the cultivation of which humanity can arrive at the art and science of collective practice of spiritual fraternity that is indispensable for everlasting peace and harmony on the Earth.

Yoga is the greatest gift that India can present to the world and in this context, readers will, it is hoped, appreciate the value of this volume.

D.P. CHATTOPADHYAYA, M.A., LL.B., Ph.D. (Calcutta and London School of Economics), D. Liu., (Honoris Causa), studied, researched on Law, philosophy and history and taught at various Universities in India, Asia, Europe and USA from 1954 to 1994. Founder-Chairman of the Indian Council of Philosophical Research (1981-1990) and President-cum-Chairman of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla (1984-1991), Chattopadhyaya is currently the Project Director of the multidisciplinary ninety-six volume Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy and Culture (PHISPC) and Chairman of the Centre for Studies in Civilizations (CSC). Among his 37 publications, authored 19 and edited or co-edited 18, are Individuals and Societies (1967); Individuals and W01-ldS (1976); Sri Aurobindo and Karl Marx (1988); Anthropology and Historiography of Science (1990); Induction, Probability and Skepticism (1991); Sociology, Ideology and Utopia (1997); Societies, Cultures and Ideologies (2000); Interdisaplinary Studies in Science, Society, Value and Civilizational Dialogue (2002); Philosophy of Science, Phenomenology and Other Essays (2003); Philosophical Consciousness and Scientific Knowledge: Conceptual Linkages and Civilizational Background (2004); Self, Society and Science:

Theoretical and Historical Perspectives (2004); Religion, Philosophy and Science (2006); Aesthetic Theories and Forms in Indian Tradition (2008) and Love, Life and Death (2010). He has also held high public offices, namely, of Union cabinet minister and state governor. He is a Life Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and a Member of the International Institute of Philosophy, Paris. He was awarded Padma Bhushan in 1998 and Padmavibhushan in 2009 by the Government of India.

KIREET JOSHI, Education Advisor to the Chief Minister of Gujarat, was earlier Registrar of Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education, Pondicherry (till 1976), Education Adviser to Government of India (1976-77) and Special Secretary in the Union Ministry of Human Resource Development (1983-88). He was also Chairman of Indian Council of Philosophical Research for two terms (2000- 2006), Chairman of Auroville Foundation (1999-2004), Member-Secretary of Rashtriya Veda Vidya Pratishthan (1987-1993) and Vice-Chairman of the UNESCO Institute of Education, Hamburg (1987-1989). He is currently staying in Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Puducherry. Among his 48 publications, 28 authored, 17 edited and 3 compiled, are A National Agenda for Education; Education for Character Development, Education far Tomorrow; Education at Crossroads; Sri Aurobindo and Integral Yoga; Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, Landmarks of Hinduism; The Veda and Indian Culture; Glimpses of Vedic Literature; The Portals of Vedic Knowledge; Bhagavad Gita and Contemporary CrisiS; Philosophy and Yoga of Sri Aurobindo and Other Essays; A Philosophy of Evolution far the Contemporary Man; Consciousness, Indian Psychology and Yoga; The Aim of Life; The Good Teacher and the Good Pupil; Mystet) and Excellence of Human Body; Gods and the Warld; Nala and Damasanti; Alexander the Great; Siege of Tray; Homer and the Iliad; Sri Aurobindo and Ilion; Catherine the Great, Paroati's Tapasya; Sri Krishna in Vrindavan; Socrates; Nachiketas; Sri Rama; Child, Teacher and Teacher Education and Philosophy of Supennind and Contemporary Crisis.

This Volume is a part of a 4-Part series on the theme of Yoga, and the main argument of this Volume is that yoga and life are inseparable and that in the evolutionary movement of life on the earth, the theme of the synthesis of yoga as a conscious and deliberate application of the highest psychological development of human consciousness has become indispensable today as an aid to the solution of the evolutionary crisis through which humanity is passing at present as also for the development of the upward mutation of the human species. In this context, the history of synthesis of yoga which began with the Vedas and the Upanisads and the new synthesis of yoga that has been proposed and worked out by Sri Aurobindo, can be regarded as a valuable gift that India is able to present today for purposes of the highest and integral welfare of humanity.

. I should like to place on record my sincere gratitude to Professor D.P. Chattopadhyaya for having provided to me a rare opportunity to edit this Volume. I should also like to thank him for the constant guidance and inspiration that he has given to me throughout the development of this Volume .

I should also like to place on record my gratitude to the learned scholars who have contributed their papers to this Volume. I should also like to mention that Professor R. Balasubramanian has been extremely kind to help me in planning this Volume and also in suggesting how this Volume could be enriched in several ways. I am also thankful to him for introducing to me a number of scholars who have extended their help by their advice and by actively participating in the seminars that were held in connection with this Volume and by contributing their papers at these seminars and permitting me to include them in this Volume. .

The help that I have received from Shri A.K. Sen Gupta, Resident Editor of the Project, has proved to be inestimable, and I should like to place on record my gratitude to him.

I have also received kind help and meticulous assistance from my colleagues, Mrs. Rekha Rathi and Mrs. Mandakini Kabra. I should like to record my debt to them and my gratefulness.

It is understandable that man, shaped by Nature, would like to know Nature. The human ways of knowing Nature are evidently diverse, theoretical and practical, scientific and technological, artistic and spiritual. This diversity has, on scrutiny, been found to be neither exhaustive nor exclusive. The complexity of physical nature, life-world and, particularly, human mind is so enormous that it is futile to follow a single method for comprehending all the aspects of the world in which we are situated.

One need not feel bewildered by the variety and complexity of the worldly phenomena. After all, both from traditional wisdom and our daily experience, we know that our own nature is not quite alien to the structure of the world. Positively speaking, the elements and forces that are out there in the world are also present in our body- mind complex, enabling us to adjust ourselves to our environment. Not only the natural conditions but also the social conditions of life have instructive similarities between them. This is not to underrate in any way the difference between the human ways of life all over the world. It is partly due to the variation in climatic conditions and partly due to the distinctness of production-related tradition, history and culture. Three broad approaches are discernible in the works on historiography of civilization, comprising science and technology, art and architecture, social sciences and institutions. Firstly, some writers are primarily interested in discovering the general laws which govern all civilizations spread over different continents. They tend to underplay what they call the noisy local events of the external world and peculiarities of different languages, literatures and histories. Their accent is on the unity of Nature, the unity of science and the unity of mankind. The second group of writers, unlike the generalist or transcendentalist ones, attach primary importance to the distinctiveness of every culture. To these writers’ human freedom and creativity are extremely important and basic in character. Social institutions and the cultural articulations of human consciousness, they argue, are bound to be expressive of the concerned people's consciousness. By implication they tend to reject concepts like archetypal consciousness,

universal mind and providential history. There is a third group of writers who offer a composite picture of civilizations, drawing elements both from their local and common characteristics. Every culture has its local roots and peculiarities. At the same time, it is pointed out that due to demographic migration and immigration over the centuries an element of compositeness emerges almost in every culture. When, due to a natural calamity or political exigencies people move from one part of the world to another, they carry with them, among other things, their language, cultural inheritance and their ways of living.

In the light of the above facts, it is not at all surprising that comparative anthropologists and philologists are intrigued by the striking similarity between different language families and the rites, rituals and myths of different peoples. Speculative philosophers of history, heavily relying on the findings of epigraphy, ethnography, archaeology and theology, try to show in very general terms that the particulars and ulJiJ'efsal§ of culture are 'es entialJy' or 'secretly' interrelated. The piritual aspects of culture like dance and music, beliefs pertaining to life, death and duties, on analysis, are found to be mediated by the material forms of life like weather forecasting, food production, urbanization and invention of script. The transition from the oral culture to the written one was made possible because of the mastery of symbols and rules of measurement. Speech precedes grammar, poetry and prosody. All these show how the 'matters' and 'forms' of life are so subtly interwoven.

The PHISPC publications on History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, in spite of their unitary look, do recognize the differences between the areas of material civilization and those of ideational culture. It is not a work of a single author. or is it being executed by a group of thinkers and writers who are methodologically uniform or ideologically identical in their commitments. In conceiving the Project we have interacted with, and been influenced by, the writings and views of many Indian and non-Indian thinkers.

The attempted unity of this Project lies in its aim and inspiration. We have in India many scholarly works written by Indians on different aspects of our civilization and culture. Right from the pre-Christian era to our own time, India has drawn the attention of various countries of Asia, Europe and Africa. Some of these writings are objective and informative and many others are based on insufficient information and hearsay, and therefore not quite reliable, but they have their own value. Quality and view-points keep on changing not only because of the adequacy and inadequacy of evidence but also, and perhaps more so, because of the bias and prejudice, religious and political conviction, of the writers. Besides, it is to be remembered that hj,stofJ~ like lat(Jre, i s« an open 600k to ?e read alike by all. The past is mainly enclosed and only partially disclosed. History IS, therefore, partly objective or 'real' and largely a matter of construction. This is one of the reasons why some historians themselves think that it is a form of literature or art. ~owe~er, it. do~s not mean that historical construction is 'anarchic' and arbitrary. Certainly, imaginauon plays an important role in it.

But its character is basically dependent upon the questions which the historian raises and wants to understand or answer in terms of the ideas and actions of human ~eings in t~e past ages. In a way, history, somewhat like the natural sciences, is engaged In answenng questions and in exploring relationships of cause and effect between events and developments across time. While in the natural sciences, the scientist poses questions about nature in the form of hypotheses, expecting to elicit authoritative answers to such questions, the historian studies the past, partly for the sake of understanding it for its own sake and partly also for the light which the past throws culture. The material conditions which substantially shaped Indian civilization have been discussed in detail. From agriculture and industry to metallurgy and technology, from physics and chemical practices to the life sciences and different systems of medicines-all the branches of knowledge and skill which directly affect human life- form tne neart of tnrs Project. Since the periods covered by the PHI PC are extensive- prehistory, proto-history, early history, medieval history and modern history of India-we do not claim to have gone into all the relevant material conditions of human life. We had to be selective. Therefore, one should not be surprised if one finds that only some material aspects of Indian civilization have received our pointed attention, while the rest have been dealt with in principle or only alluded to.

One of the main aims of the Project has been to spell out the first principles of the philosophy of different schools, both pro-Vedic and anti-Vedic. The basic ideas of Buddhism, jainism and Islam have been given their due importance. The special po ition accorded to philosophy is to be understood partly in terms of its proclaimed unifying character and partly to be explained in terms of the fact that different philosophical systems represent alternative world-views, cultural perspectives, their conflict and mutual assimilation.

Most of the volume-editors and at their instance the concerned contributors have followed a middle path between the extremes of narrativism and theoreticism. The underlying idea has been this: if in the process of working out a comprehensive Project like this every contributor attempts to narrate all those interesting things that he has in the back of his mind, the enterprise is likely to prove unmanageable. If, on the other hand, particular details are consciously forced into a fixed mould or pre-supposed theoretical structure, the details lose their particularity and interesting character. Therefore, depending on the nature of the problem of discourse, most of the writers have tried to reconcile in their presentation, the specificity of narrativism and the generality of theoretical orientation. This is a conscious editorial decision. Because, in the absence of a theory, however inarticulate it may be, the factual details tend to fall apart. Spiritual network or theoretical orientation makes historical details not only meaningful but also interesting and enjoyable.

Another editorial decision which deserves spelling out is the necessity or avoidability of duplication of the same theme in different volumes or even in the same volume. Certainly, this Project is not an assortment of several volumes. Nor is any volume intended to be a miscellany. This Project has been designed with a definite end in view and has a structure of its own. Tbe character Df.tbr.strn.c..tw'£.Jy~/~~' «"'-"'''''' @-,/7~~>r",.ru--r,pz:fu>. F&ne-e), o[tffe (flemes accommodated ithi it A " ' b d WI mi. gain It must Pn ~n e:stood that the complexity of structure is rooted in the aimed integrality of the reject Itself.

L.ong) and in-depth ~ditorial discussion has led us to several unanimous conclusions trst y, our Project IS going to be' . 11 d '. . '. unique, unrrva e and di.scursive in its attempt to mtegrate dIfferent forms of science, technology, philosophy and culture. Its comprehensive scope, continuous character and accent on culture distinguish it from the works of such Indian authors as P.C. Ray, B. . Seal, Binoy Kumar Sarkar and S.N. Sen and also from such Euro-Arnerican writers as Lynn Thorndike, George Sarton and Joseph eedham. Indeed, it would be no exaggeration to suggest that it is for the first time that an endeavour of so comprehensive a character, in its exploration of the social, philosophical and cultural characteristics of a distinctive world civilization-that of India-has been attempted in the domain of scholarship.

Secondly, we try to show the linkages between different branches of learning as different modes of experience in an organic manner and without resorting to a kind of reductionism, materialistic or spiritualistic. The internal dialectics of organicism without reductionism allows fuzziness, discontinuity and discreteness within limits.

Thirdly, positively speaking, different modes of human experience-scientific, artistic, etc.-have their own individuality, not necessarily autonomy. Since all these modes are modification and articulation of human experience, these are bound to have between them some finely graded commonness. At the same time, it has been recognized that reflection on different areas of experience and investigation brings to light new insights and findings. Growth of knowledge requires humans, in general, and scholars, in particular, to identify the distinctness of different branches of learning.

Fourthly, to follow simultaneously the twin principles of: (a) individuality of human experience as a whole, and (b) individuality of diverse disciplines, is not at all an easy task. Overlap of themes and duplication of the terms of discourse become unavoidable at times. For example, in the context of Dharmasastra, the writer is bound to discuss the concept of value. The same concept also figures in economic discourse and also occurs in a discussion on fine arts. The conscious editorial decision has been that, while duplication should be kept to its minimum, for the sake of intended clarity of the themes under discussion, their reiteration must not be avoided at high intellectual cost.

Fifthly, the scholars working on the Project are drawn from widely different disciplines. They have brought to our notice an important fact that has clear relevance to our work. Many of our contemporary disciplines like economics and sociology did not exi t, at least not in their present form, just two centuries ago or so. For example, before the middle of the nineteenth century, sociology as a distinct branch of knowledge was unknown. The term is said to have been coined first by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in 1838. Obviously, this does not mean that the issues discussed in sociology were not there. Similarly, Adam Smith's (1723-90) famous work The Wealth of Nations is often referred to as the first authoritative statement of the principles of (what we now call) economics. Interestingly enough, the author was equally interested in ethics and jurisprudence. It is clear from history that the nature and scope of different di ciplines undergo change, at times very radically, over time. For example, in ancients India arthasiistra did not mean the science of economics as understood today. Besides the principles of economics, the Arthasastra of Kautilya discusses at length those of governance, diplomacy and military science.

Sixthly, this brings us to the next editorial policy followed in the Project. We have tried to remain very conscious of what may be called indeterminacy or inexactness of translation. When a word or expression of one language is translated into another, some loss of meaning or exactitude seems to be unavoidable. This is true not only in the bilingual relations like Sanskrit-English and Sanskrit-Arabic, but also in those of Hindi-Tamil and Hindi-Bengali. In recognition of the importance of language-bound and context-relative character of meaning we have solicited from many learned scholars, contributions written in vernacular languages. In order to minimize the miseffect of semantic inexactitude we have solicited translational help of that type of bilingual scholars who know both English and the concerned vernacular language, Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Bengali or Marathi.

Seventhly and finally, perhaps the place of technology as a branch of knowledge in the composite universe of science and art merits some elucidation. Technology has been conceived in very many ways, e.g., as autonomous, as 'standing reserve', as liberating or enlargemental, and alienative or estrangemental force. The studies undertaken by the Project show that, in spite of its much emphasized mechanical and alienative characteristics, technology embodies a very useful mode of knowledge that is peculiar to man. The Greek root words of technology are techne (art) and logos (science). This is the basic justification of recognizing technology as closely related to both epistemology, the discipline of valid knowledge, and axiology, the discipline of freedom and values. It is in this context that we are reminded of the definition of man as homo technikos. In Sanskrit, the word closest to techne is kala which means any practical art, any mechanical or fine art. In the Indian tradition, in Saiuatantra, for example, among the arts (kala) are counted dance, drama, music, architecture, metallurgy, knowledge of dictionary, encyclopaedia and prosody. The closeness of the relation between arts and sciences, technology and other forms of knowledge are evident from these examples and was known to the ancient people. The human quest for knowledge involves the use of both head and hand. Without mind, the body is a corpse and the disembodied mind is a bare abstraction. Even for our appreciation of what is beautiful and the creation of what is valuable, we are required to exercise both our intellectual competence and physical capacity. In a manner of speaking, one might rightly affirm that our psychosomatic structure is a functional connector between what we are and what we could be, between the physical and the beyond. To suppose that there is a clear-cut distinction between the physical world and the psychosomatic one amounts to denial of the possible emergence of higher logico-mathematical, musical and other capacities. The very availability of aesthetic experience and creation proves that the supposed distinction is somehow overcome by what may be called the bodily self or embodied mind.

| Table of Transliteration | ||

| International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) | Xl | |

| Preface | Xli | |

| Kireet Joshi | XIII | |

| General Introduction | XV | |

| D.P. Chattopadhyaya | XXV | |

| Editors | XXVii | |

| Contributors | ||

| Introduction | XXXV | |

| Kireet Joshi | ||

| Synthesis of Yoga: Prefatory Remarks | ciii | |

| D.P. Chattopadhyaya | ||

| 1. | Earliest Records of Synthesis of Yoga | 1 |

| Kireet Joshi | ||

| 2. | Synthetic Origin of Yoga in the Veda | 99 |

| S.P. Singh | ||

| 3. | Synthesis of Yoga in the Upanisads | 115 |

| N. Jayashanmugam | ||

| 4. | The Gita and its Synthesis of Yoga | 135 |

| Kireet Joshi | ||

| 5. | The Synthesis of Yoga in Buddhism | 219 |

| Wangchuk Dorjee Negi | ||

| 6. | A Synthesis of Faith, Knowledge and Conduct: The Jain Perspective of Synthetic Yoga | 237 |

| Dayanand Bhargava | ||

| 7. | Patafijali's Yoga-A Synthesis | 245 |

| Rama Jain | ||

| 8. | Taoism as a Paradigm of the Synthesis of Yoga | 257 |

| S. Shyam Kishore Singh | ||

| 9. | Synthesis of Yoga in Saiva Siddhanta | 269 |

| S. Ram Mohan | ||

| 10. | Synthesis of Yoga in Tantra with Special Reference to the Siddhas | 303 |

| T.N. Ganapathy | ||

| 11. | Synthesis of Yoga in the Puranas (with Special Reference to Astanga-yoga) 353 | 353 |

| Gangadhar Panda | ||

| 12 | Synthesis of Yoga in Srimad Bhagavata | 379 |

| c.c. Nayak | ||

| 13 | Synthesis of Yoga in the Tantric (Saiva-Sakta) Tradition | 393 |

| Kamalakar Mishra | ||

| 14 | Synthesis of Different Yogas in Jain Tantricism | 409 |

| Sagarmal Jain | ||

| 15 | Synthesis of Yoga in Vedantic Systems | 423 |

| R. Balasubramanian | ||

| 16 | Synthesis of Yoga in Vaisnavism of Rarnanuja | 467 |

| S.M. S. Chari | ||

| 17 | Synthesis of Yoga in the Bhakti Movement | 485 |

| Prema Nandakumar | ||

| 18 | Synthesis of Yoga in Lingayatism | 505 |

| N. G. Mahadevappa | ||

| 19 | .Multiplex Concepts of Yoga: As Per the Philosophical framework of Vallabha Vedanta | 527 |

| Shyam Manohar Goswami | ||

| (Translated from original Hindi into English by Achyutananda Dash) | ||

| 20 | .Yoga of Synthesis in Kashmir Saivism | 549 |

| S.S. Toshkhani | ||

| 21 | .Guru Nanak on Yoga in the Medieval Period | 583 |

| Jodh Singh | ||

| 22 | Synthesis of Yoga in the Philosophy of Caitanya Mahaprabhu | 591 |

| Satya Narayan Das | ||

| 23 | Synthesis of Yoga in the Teachings of the Baha'i Faith | 625 |

| A.K. Merchant | ||

| 24 | Synthesis of Yoga in Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda | 643 |

| Godabarisha Mishra | ||

| 25 | Synthesis of Yoga in Akhanda Mahayoga | 669 |

| S.I. Tripathi | ||

| 26 | Our Need of a New Synthesis of Yoga(A Journey to the theme of Manifestation of Supramental Consciousness in Matter) | 705 |

| Kireet Joshi | ||

| 27 | Yoga and Knowledge | 783 |

| Aparna Banerjee | ||

| 28 | Sapta Chatusthaya: Sri Aurobindo's Agenda for Yoga | 795 |

| A. K. Sen Gupta | ||

| 29 | Mother's Agenda (An Introductiry Essay) | 831 |

| Jyoti Madhok | ||

| 30 | Satprem and Evoltion II in Synthesis of Yoga | 853 |

| kireet Joshi | ||

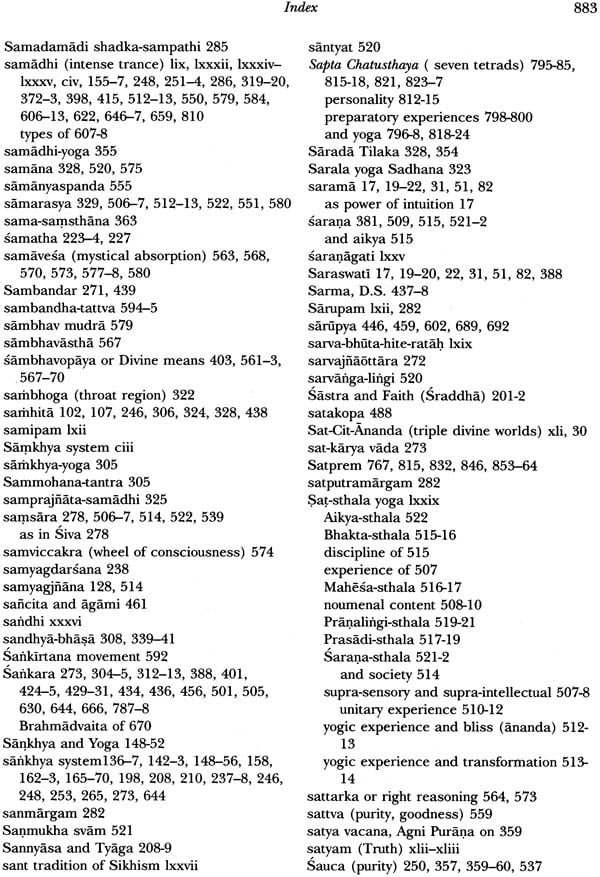

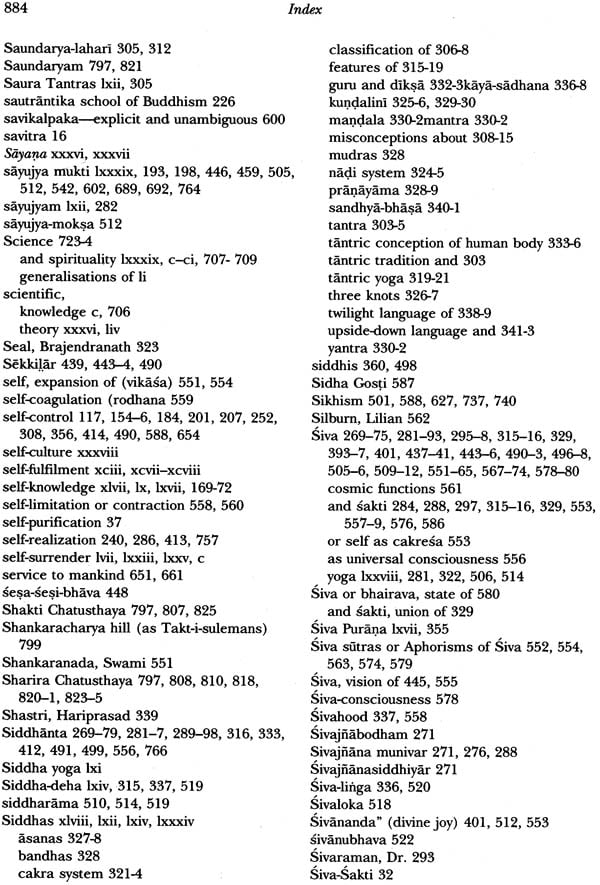

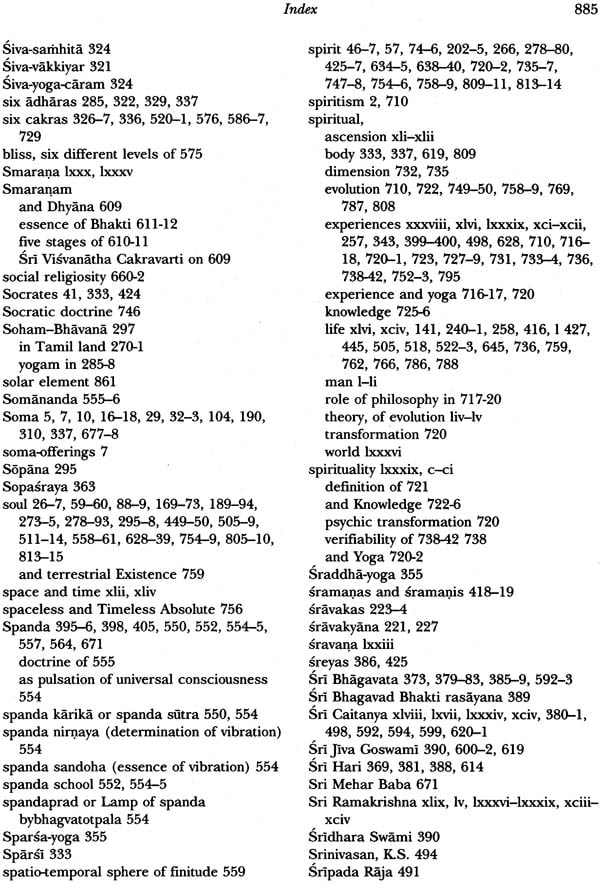

| Index | 865 |