Integral Revolution:An Analytical Study of Gandhian Thought (An Old and Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAV492 |

| Author: | Indu Tikekar |

| Publisher: | Sarva Seva Sangh Prakashan, Varanasi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1970 |

| Pages: | 286 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 300 gm |

Book Description

To those of us who were young when Gandhi made his first powerful impact on the Indian political scene in 1920-21, by launching the Non-violent Non-cooperation movement, and who witnessed his phenomenal rise from a mere non-entity in politics before 1920, to the amazing height of practically becoming the sole arbiter of our national destiny, Gandhi has always meant much more than what he said or did, or what others said or did under his inspiration. The phenomenon of Gandhi remains a riddle despite the efforts made by historians, philosophers, moralists, religious and socio-political thinkers to ex-plain it. All this massive effort leaves the main question still unanswered : What exactly was it that made it possible for Gandhi to move millions to respond spontaneously to his unprecedented and unpreme-ditated call for a non-violent revolution as a way out of the inhuman domination for the mighty British Empire—a call that actually crystalised into a concrete fact of the political emancipation of India within the small span of only twenty seven years?

To most of us who not merely witnessed but actually participated in the socio-political upheavals of the times, no answer so far attempted to explain this everchallenging phenomenon seems adequate enough to ring true in our hearts. The tradition-bound mind of India has been, and still remains, a sphinx-like colossus. It never responded to the calls for socio-political changes on such a massive scale, throughout its history of not less than five thousand years. It did respond to the call of the Buddha, the Enlightened One, on a gigantic scale—a call that excercised its self-illuminating spell on India and Asia for over a thousand years. But it was wholly a non-political call. It was a call to awaken man to a dynamic awareness of his identity, uninfluenced by external pressures and internal tensions. It was a call to stand alone and be a light unto one-self, and move on this earth to awaken fellow human beings to their existential destiny. And strangely enough, this aloneness unified isolated identities of millions in India and Asia in a manner that still re-mains a challenging mystery to the intelligence of man.

To explain man and the radical changes in human life he brings about, in terms of external environmental pressures and internal conditionings, is to repeat ad museum pre-established formulas of comprehension which tend to equate words with things and the ever strange reality with the familiar patterns of recognition. The words that Gandhi used, such as, Truth and Non-violence, were so well-known in India right from the ancient Vedic times that to describe Gandhi as an 'Apostle of Truth and Non-violence' is to explain the living new in terms of the dead old. It is like explaining the workings of a living organism in terms of the findings of postmortem examinations. Such post-mortem ways of understanding man and the social changes he brings about, have become so popular and respectable that seeing their continuing influence on the minds of men, one is left wondering whether men, in general, all over the world are at all interested in truth and right understanding Prophets of ever new action thus get submerged in the refuge of verbalisations, mounting up to the menacing proportions of ecological pollutions.

It is often forgotten that the problem of understanding man and the changes that are brought about in human life through his actions, is, basically, a problem of understanding oneself through the creative processes of self-knowledge. As Ortega y Gasset, rightly called the `master of the philosophical essay', puts it ; "To understand other people, I have nothing else to resort to than the-stuff that is my life. Only my life has of itself 'meaning' and is, therefore, intelligible. The situation seems ambiguous, and so it is in a way. With my own life I must understand precisely what it is in alien life that makes it distinct and strange to mine. My life is the universal interpreter. And history as an intellectual discipline is the man does not seem to be irremediably bound to be other than I for all time to come. "I continue to feel that, in principle, he could be I. Love and friendship live on this belief and this hope; they are extreme forms of assimilation between the I and the you." (Ibid) Men, in general, lack love and friendship in as much as most of their relationships are the products of built-in likes and dislikes rooted in their fearful, conditioned and petty ego-centric psyche. Most of us are afraid of almost everything that is not the me and the mine. It calls for a transcendence of the me and the mine, and the emergence of an 'intellectual unselfishness' in harmony with love and friendship, to under-stand the other. According to Ortega, "the technique of such intellectual unselfishness is called history."

Gandhi is already a part of history. And the only way open to me, or to any one, to understand his life and work is "to assimilate myself imaginatively to him". This could be possible only if I am really anxious to abandon myself into the undefined realm of a truth-finding enquiry inspired by a passion for understanding Gandhi in terms of my own life as a human being. Most of us who lived in the times of Gandhi felt charged with a vision of an emergence of a new mind and a new world in which, not the compulsions of modern technology or of ideologies based on them, but the self-realised imperatives of the supreme importance of truth and friendliness for men all over the world, would be the decisive fac-tors in the shaping of human destiny. But now, unfortunately, as we look at India of the post-Gandhi era, we are overwhelmed with a feeling of intense existential despair. From the moment Gandhi fell down as a result of bullet-shots fired by a fanatic, he was reduced to a repetitive ritual of a set of words he frequently used while he was alive—words from which the vital things they then conveyed had been totally squeezed away. There are still a few valiant souls who are, ever-since the death of Gandhi, carrying on tirelessly the work which was dear to him. There is, for instance, Vinoba, rightly described as the spiritual successor of Gandhi, whose work as the pioneer of the Land-gift movement has attracted world-wide attention. But despite this work, pregnant with revolutionary implications, India presents today a picture of a 'free' nation which has become as alien to Gandhi and his teachings as any other nation. The fire of a new dimensional revolution, lit up by systematic endeavour to make of any other human being an alter ego, in which expression both terms—the alter and the ego—must be taken at their full value. Here lies the ambiguity, and this is why the situation presents a problem to reason." (In the section entitled, "Prologue to a History of Philosophy" of Ortega's book "Concord and Liberty"—Norton paperback ).

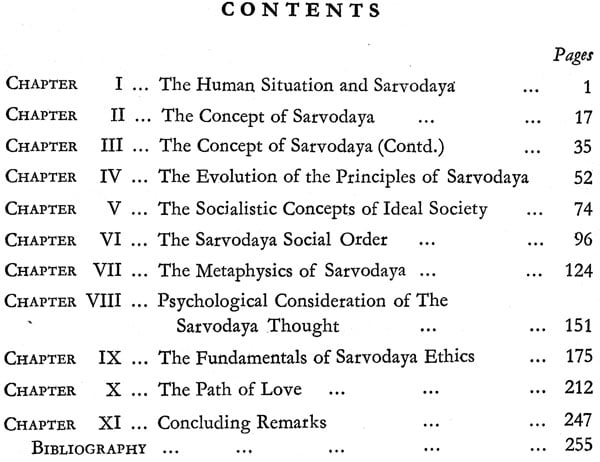

**Contents and Sample Pages**