Not Far From the River- Love Poems from Gatha Saptasati (A 2nd Century Prakrit Work)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAB401 |

| Author: | David Ray |

| Publisher: | Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur |

| Language: | Prakrit and English |

| Edition: | 1983 |

| Pages: | 208 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inches |

| Weight | 300 gm |

Book Description

The famous Thera-gatha and Theri-Gatha are well known collections of verses composed by monks and nuns. These collections attest to the antiquity of the Prakrit lyricism in the gatha form.

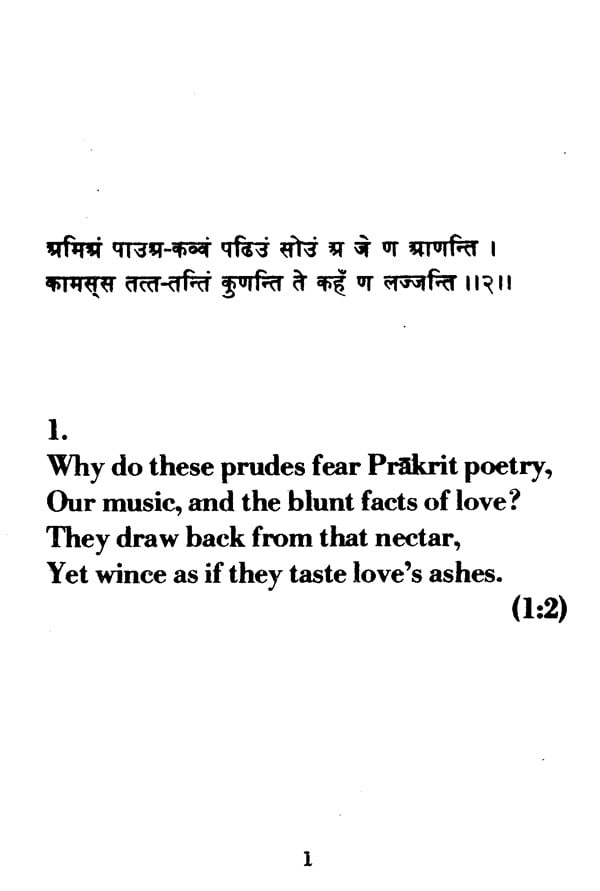

While the earlier surviving phase of this lyrical tradition is dominated by the feeling of Weltschmerz, it apparently underwent a sea-change in the early centuries of the Christian era. The Satavahana rulers of the Deccan patronized Prakrit as well as the plastic arts. The aesthetic milieu of the age emphasized the beauty of sensuous form as also the emotional responses which it generated.

Henceforth love and beauty remained central to the poetic tradition in India.

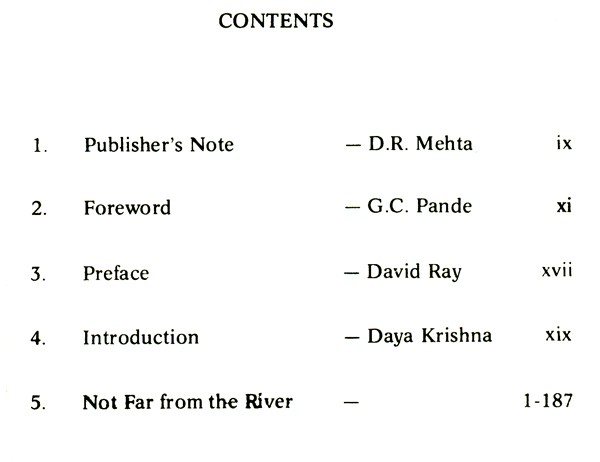

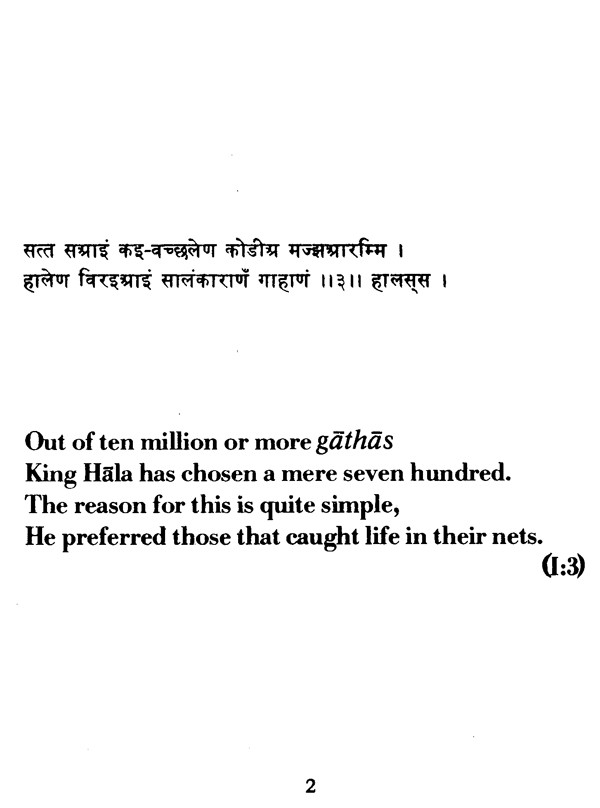

The Seven Hundred Gathas compiled by King Hala is the earliest example of a genre which was widely cultivated and imitated later in Sanskrit as well as Hindi.

One has only to recall the names of Amaruka, Goverdhana, and Bihari to see the influence which these gathas exercised. The late Pandit Mathura Nath Shastri who was one of the greatest classicists of modern Rajasthan has shown this amply in his Sanskrit introduction of his edition of the present work of the "Kavya-Mala".

The authorship of the work and also the final date of its compilation are uncertain. The substance of the work, however, appears to belong to the Satavahana period, namely, the second and third century A.D. Whether the reference to Vikramaditya proves the historicity of the ruler or the lateness of the present work is a matter of dispute. In a collection like this, it is difficult to vouch for the authenticity of each verse, though skepticism too would require to be reasoned. In any case, the world of Hala would bear comparison with that of Sudraka or Gundhya in its intensity of passion and the refinement of civilization, even though much of its landscape is rural and natural.

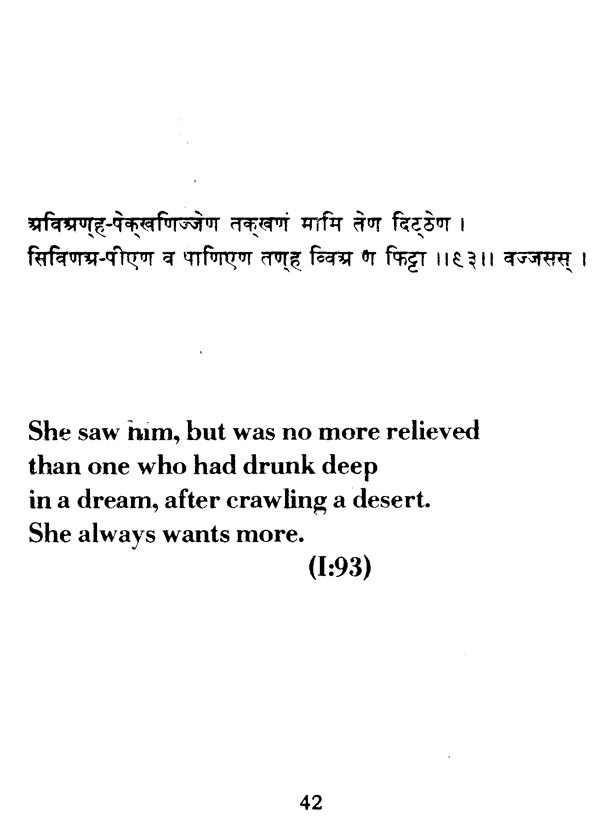

Perhaps, David was King Hala himself or someone close to him who helped in the compilation, and all of us the courtiers around who enjoyed the collection and the recitation. It may sound unbelievable-and it is-but how else shall we explain the extraordinary fact that none of us-Amrita, Francine, David, myself-were even remotely aware of the Gatha when, all of a sudden, we were all involved in it and are still trying to disentangle what the lovers and the poets have tangled into "subtle knots". In these verses, the body, the mind and the spirit are not only fused together but also confuse one another so that none knows whether flesh seeks flesh, mind seeks mind, or soul seeks soul to create a reality which is perhaps only in the relationship and not in the separate units themselves.

The story of the translation or transcription itself is both instructive and strange. The very fact that there is no single word or even set of words to describe the situation be- speaks the baiting ambiguity of the situation. David has no knowledge of Prikrit, the language in which the Couplets were first composed. Nor does he know anything of Sanskrit which may be deemed to come closest to the Prakrit original. Yet, he not only dared to undertake what would appear to every scholar an obvious folly but dared so successfully that all those around got interested and involved in the project.

True, the enterprise is not new. Vidya Nivas Mishra had already tried the experiment with Hindi poetry at Berkeley earlier. Josephine Miles, Leonard Nathan and others who did not know any Hindi, successfully translated (if that is the word) the poems from the rhythms caught from Vidya Nivas's recitation on the tape and the text of his prose- rendering of the poems into English.' But, then what is translated or caught in such a situation is difficult to tell. Is it what they call the poetic meaning or the mood or even what the Indian aestheticians have called rasa? Whatever it be, it is something the readers enjoy, something which makes one connect, puts one in touch with that which otherwise would have remained unfelt, unlived, unrealized in the sensitivity of those who did not know the language at all or well enough to realize the living potential of the original.

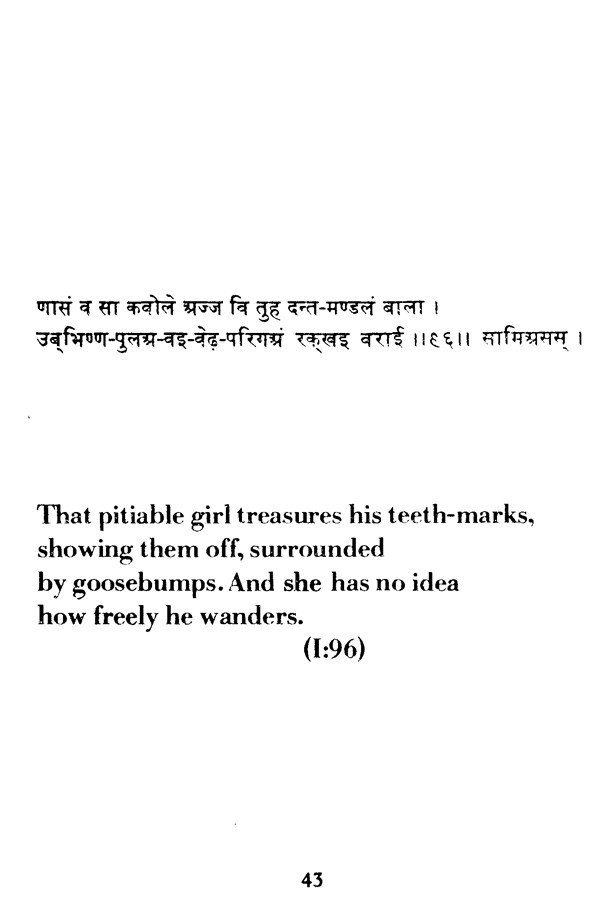

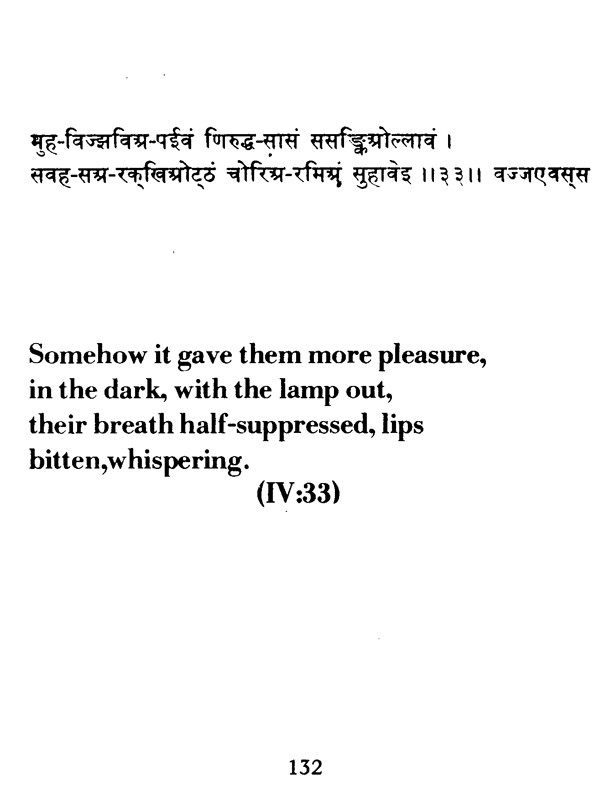

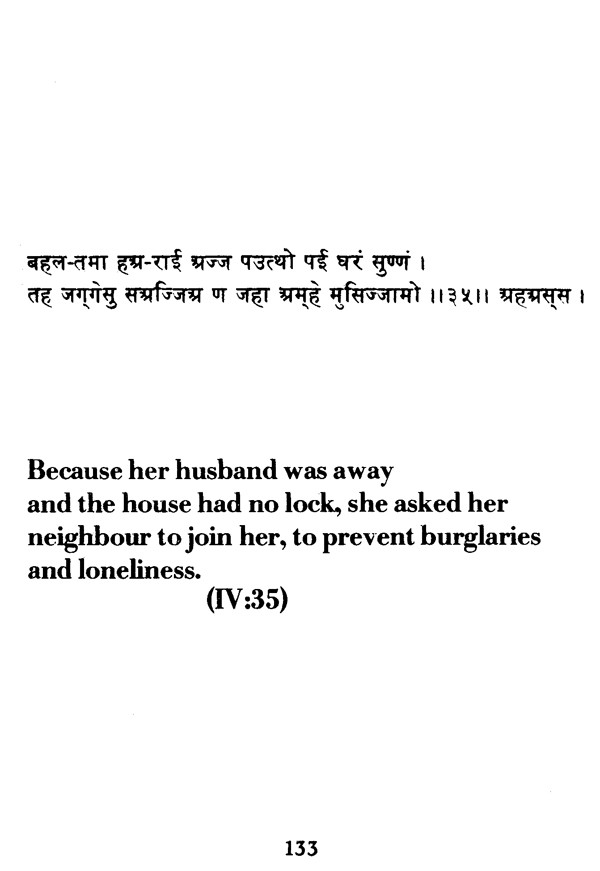

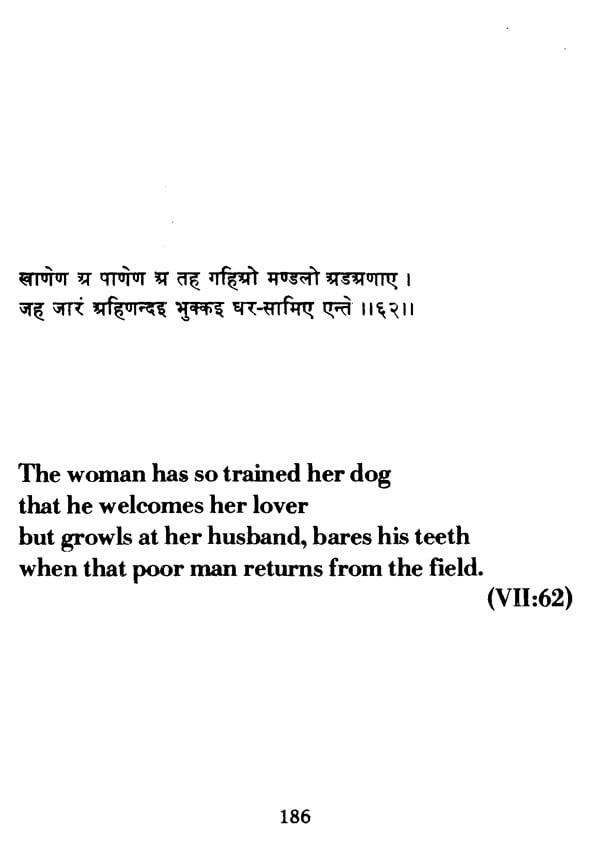

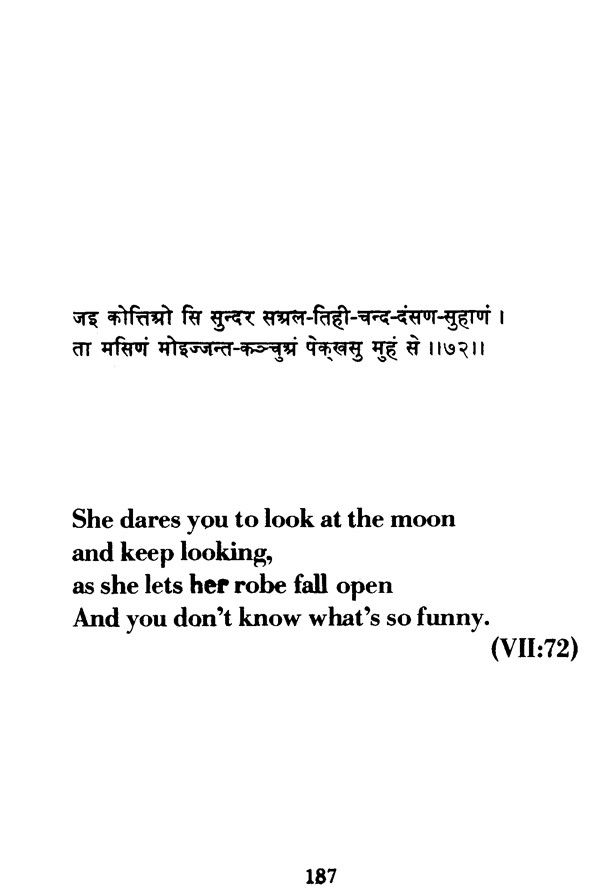

Book's Contents and Sample Pages