2500 Years of Buddhism

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IHF035 |

| Author: | P.V. Bapat |

| Publisher: | Publications Division, Government of India |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9788123017082 |

| Pages: | 437 (4 B/W (Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.4” X 5.4” |

| Weight | 600 gm |

Book Description

The book gives a short account of Buddhism in the last 2500 years. The foreword for the book was written by Dr. Radhakrishnan, world renowned philosopher. The book contains 16 chapters and about one hundred articles written by eminent Buddhist scholars from India, China, Japan, Sri Lanka, Nepal.

Buddhism is a way of life of purity in thinking speaking and acting. This book gives an account of Buddhism not only in India but also in other countries of the East. Detailed and insightful glimpse into the different schools and sects of Buddhism find a place in this book. Buddhist ideas on education and the prevailing state of Buddhism as revealed by their Chinese pilgrims who visited India during that times are other components of the book. Chapters on Buddhist art in India and abroad and places of Buddhist interest are also included to give it a holistic perspective.

The spirit of Buddha comes alive in the book and enlightens the readers with his teaching so essential now for peace in the strife-torn world.

Sixth century B.C. was remarkable for the spiritual unrest and intellectual ferment in many countries. In china we had Lao Tzu and Confucius in Greece Parmenides and Empedocles in Iran Zarathustra in India Mahavira and the Buddha. In that period many remarkable teachers worked upon their inheritance and developed new points of view.

The Purnima or full-moon day of the month of Vaisakha is connected with three important events in the life of the Buddha birth enlightenment and Parinirvana. It is the most sacred day in the Buddhist calendar. According to the Theravada Buddhism the Buddha’s parinirvana occurred in 544 B.C. Though the different schools of Buddhism have their independent systems of chronology, they have agreed to consider the full-moon day of May 1956 to be the 2500th anniversary of the mahaparinirvana of Gautama the Buddha. This book gives a short account of the story of Buddhism in the last 2500 years.

The main events of the Buddha’s life are well known. He was the son of a minor ruler of Kapilavastu grew up in luxury; married Yasodhara had a son Rahula and led a sheltered life where the world’s miseries were hidden. On four occasions when he went out of his palace, so the legend tells us he met an old man and felt that he was subject to the frailties of age, met a sick man and felt that he was also subject to death, and met an ascetic with a peaceful countenance who had adopted the traditional way of the seekers of religious truth. The Buddha resolved to gain freedom from old age, sickness and death by following his example. The mendicant tells the Buddha.

I am a sramanah an ascetic who in fear of birth and death have left home life to gain liberation.

The sight of the holy man, health in body cheerful in mind without any of the comforts of life impressed the Buddha strongly with the conviction that the pursuit of religion was the only goal worthy of man. It makes man independent of the temporary trails and fleeting pleasures of the world. The Buddha decided to renounce the world and devote himself to a religious life. He left his home wife and child put on the garb and habit of a mendicant and fled into the forest in order to medicate on human suffering its causes and the means by which it could be overcome. He spent six years in the study of the most abstruse doctrines of religions suffered the severest austerities reduced himself to the verge of the starvation in the hope that by mortifying the flesh he should surely attain to the knowledge of truth. But he came very near to death without having attained the wisdom that he sought. He gave up ascetic practices resumed normal life refreshed himself in the waters of the river Nairanjana accepted the milk pudding offered by sujata nayam attma balahinena labhyah. After he gained bodily health and mental vigour he spent seven weeks under the shade of the Bodhi tree, sitting in a stage of the deepest and most profound meditation. One night towards the dawn his understanding opened and he attained enlightenment. After the enlightenment the Buddha refers to himself in the third person as the tathagata; he who has arrived at the truth. He wished to preach the knowledge he gained and so said. I shall go to Banaras where I will light the lamp that will bring light unto the world. I will go to Banaras and beat the drums that will awaken mankind. I shall go to Banaras and three I shall teach the Law. Give ear 0 medicine. The Deathless has been found by me. I will now instruct. I will preach the Dharma. He traveled from place to place touched the lives of hundreds high and low princes and peasants. They all came under the spell of his great personality. He taught for forty-five years the beauty of charity and the joy of renunciation the need for simplicity and equality.

At the age of eighty he was on his way to Kusinagara the town in which he passed into parinirvana. Taking leave of the pleasant city of Vaisali with his favourite disciple Ananda he rested on one of the neighboring hills and looking at the pleasant scenery with its many shines and sanctuaries he said to Ananda citram jambudvipam, manoramam jivitam manusyanam. Colorful and rich is India loveable and charming is the life of men. On the banks of the river Hiranyavati in a grove of Sal trees the Buddha had a bed prepared for himself between two trees. He gently consoled his disciple Ananda. From all that he loves man must part. How could it be that what is born, what is subject to instability should not pass? Maybe you were thinking we have no longer a master. That must not be 0 Ananda. The doctrine I have preached to you is your master. He repeated.

Vayadhamma sankhara appamadena sampadetha to.

Verily I say unto you now 0 monks: All things are perishable work out your deliverance with earnestness.

There were his last words. His spirit sank into the depths of mystic absorption and when he had attained to that degree where all thought all conception disappears when the consciousness of individually ceases he entered into the supreme nirvana.

In the life of the Buddha there are two sides individual and social. The familiar Buddha image is of a mediating sage yogin absorbed and withdrawn lost in the joy of his inner meditation. This is the tradition associated with the Theravada Buddhism and Atoka’s missions. For these the Buddha is man not god a teacher and not concerned with the sorrows of men eager to enter their lives heal their troubles and spread his message for the god of the many bahu-jana-hitaya. Based on this compassion for humanity a second tradition matured in North India under the Kusanas (70-480 A.D.)and the Gupta s(320-650 A.D.). It developed the ideal of salvation for all discipline of devotion and the way of universal service. While the former tradition prevails in Cyclone Burma and Thailand the latter is found in Nepal, Tibet, Korea, China and Japan.

All forms of Buddhism however agree that the Buddha was the founder that he strove and attained transcendental wisdom as he sat under the Bodhi tree, that he pointed a way from the world of suffering to a beyond the undying and those who follow the path for liberation may also cross to the wisdom beyond. This is the root of the matter the essential unity underlying the many differences in outlook and expression that came to characterize Buddhism as it spread from India to other parts of the world.

The essence of all religious is a change in man’s nature. The conception of second birth dvittiyam janma is the central teaching of the Hindu and the Buddhism religious. Man is not one but a multiplicity. He is asleep he is an automaton. He is inwardly discordant. He must wake up become united harmonious within himself and free. The Greek mysteries implied this change in our nature. Man himself is conceived as a grain which could die as a grain but be reborn as a plant different from the grain. A bushel of wheat has two possible destinies to be pounded and made into flour and become bread or to be sown in the ground to germinate and become a plant and give a hundred grains for one that is sown. St. Paul borrowed this idea in a describing the Resurrection when he says. Thou fool that which thou so west is not quickened except it die. It is sown a natural body it is raised a spiritual body. The change is a transforming of the substance itself. Man is not a complete final being. He is being who can transform himself, who can be born again. To effect this change to be reborn to be awakened is the goal of all religious as of Buddhism.

Our subjection to time to samsara is due to avidya unawareness leading to infatuation depravity asava. Ignorance and craving are the substratum of the empirical life. From avidya we must rise to vidya bodhi enlightenment. When we have vipassana, knowledge by seeing clear perception. We will acquire samata unshakable calm. In all this the Buddha adopts the Vedic criterion of certainty which is rooted in actual knowledge which is attained by immediate experience direct intellectual intuition of reality: yatha-bhuta-nana-dassana.

The Buddha did not feel that he was announcing a new religious. He was born grew up and died a Hindu. He was restating with a new emphasis the ancient ideals of the Indo-Aryan civilization. Even so have I monks seen an way an ancient road followed by the wholly awakened ones of olden times. Along that have I gone and the matters that I have come to know fully as I was going along it I have told to the monks nuns men and women lay-followers even monks this Brahma-faring Brajmacharya that is prosperous and flourishing widespread and widely known become popular in short well made manifest for gods and men.

The quest of religious India has been for the incomparable safety fearlessness abhaya, moksa, nirvana. It is natural for man to strive to elevate himself above earthly things, to go out from the world sense to free his soul from the trammels of existence and gross materiality to break through the outer darkness into the world of light and spirit. The Buddha aims a new spiritual existence attained through jnana or bodhi absolute illumination. But I deem the highest goal of a man to be the stage in which three is neither old age nor fear nor disease nor birth, nor death, nor anxieties and in which there is no continuous renewal of activity.

naivoparamo na cadhayah

tam eva manye purustham uttamam na vidyate

yatra punah punah kriya.

The Buddha aimed at a spiritual experience in which all selfish craving is extinct and with it every fear and passion. It is a state of perfect inward peace accompanied by the conviction of having attained spiritual freedom a state which words cannot describe. Only he who has experienced it knows what it is. The state is not life in a paradise where the gods dwell. You should feel shame and indignation if ascetics of others schools ask you if it is in order to arise in a divine world that ascetic life is practiced under the ascetic Gautama. Even as the Upanishads distinguish moksa from life in brahmaloka the Buddha points out that the gods belong to the world of manifestation and cannot therefore be called absolutely unconditioned. Existence has as its correlative non-existence. The state of the mukta the Buddha is higher than that of the Brahma it is invisible resplendent and eternal. There is higher than the gods a transcendental absolute described in the Udana as ajata unborn abhuta unbecome , akata unmade asankhata uncompounded. This is the Brahman of the Upanishads which is characterized as na iti, na iti. The Buddha calls himself Brahma-bhuta he who has become Brahman. The Buddha adopted an absolutist view of Ultimate reality though not a theistic one. He felt that many abstained from action in the faith that God would do everything for them. They seemed to forget that spiritual realization is a growth from within. When the educated indulged in vain speculations about the Inexpressible the uneducated treated God as a being who could be manipulated be magic rites or sorcery. If god Buddha revolted against the ignorance and superstition the dread and the horror which accompanied popular religion. Besides theistic views generally fill men’s with dogmatism has filled the world with unhappiness injustice strife crime and hatred.

The conception of the world as samsara a stream without end where the law of karma function is common to all Indian systems, Hindu, Jain, Buddhist and Sikh. Nothing is permanent not even the gods. Even death is not permanent for it must turn to new life. The conduct of the individual in one life cannot determine his everlasting destiny. The Buddha does not accept a fatalistic view. He does not say that man has no control over his future. He can work out his future become an Arhat attain nirvana. The Buddha was an ardent exponent of the strenuous life. Our aim is to conquer time overcome samsara and the way to it is the moral path which results in illumination.

The Buddha did not concede the reality of an unchangeable self for the self is something that can be built up by good thoughts and deeds but yet he has to assume it. While karma relates to the world of objects of existence in time nirvana assumes the freedom of the subject of inwardness. We can stand out of our existential limits. We experience the nothingness the void of the world to get beyond it. To stand out of objective existence there must come upon the individual a sense of crucifixion a sense of agonizing annihilation a sense of the bitter nothingness of all the empirical existence which is subject to the law of change of death. We cry from the depths of unyielding despair. Who shall save me from the body of this death? If death is not all if nothingness is not all there is something which survives death though it cannot be described. The I is the unconditioned something which has nothing to do with the body feeling, perception, formation thought which are all impermanent changeable non-substantial. When the individual knows that what is impermanent is painful he becomes detached from them and becomes free. The indispensable prerequisite of this is a higher consciousness of an “I” or something like it. This “I” is the primordial essential self the unconditioned whose realization give us liberty and power. The self is neither body feeling consciousness etc. but from this it does not follow that there is nor self at all. The ego is not the only content of the self though it is the only content that can be known objectively. There is another side of our self which helps us to sweep away by the current of events, which is not controlled by outward circumstances which protects itself from the usurpation of society which does not submit to human opinion but jealously guards its rights. The enlightened is free having broken all binds. The ascetic is one, who has gained mastery over himself, who has his heart in his power and is not attained nirvana is far from being dissolved into non-being. It is he that becomes extinct but the passions and desires. He is no longer conditioned by the erroneous nation and selfish desires that normally go on shaping individuals. The Buddha realizes himself to be free from the characteristics that constitute an individual subject. He has vanished from the sphere of dualities. Whatever thought he desires that thought will he think whatever thought he does not desire that thought will be not think. The Buddha taught us to pursue prajana and practice compassion karuna. We will be judged not by the creeds we profess or the labels we wear or the slogans we shout but by our sacrificial work and brotherly outlook. Man weak as he is subject to old age sickness and death, in this ignorance and pride condemns the sick the aged and the dead. If anyone looks with disgust on any fellow being who is sick or old or dead, he would be unjust to himself. We must not find fault with the man who limps or stumbles along the road for we do not know the shoes he wears or the burdens he bears. If we learn what pain is we become the brothers of all who suffer.

Buddhism did not start as a new and independent religion. It was an offshoot of the more ancient faith of the Hindus perhaps a schism or a heresy. While on the fundamentals of metaphysics and ethics the Buddha agreed with the faith he inherited he protested against certain practices which were in vogue at the time. He refused to acquiesce in the Vedic ceremonialism. When he was asked to perform some of these rites he said. And as for your saying that for the sake of dharma I should carry out the sacrificial ceremonies which are customary in my family and which bring the desired fruit I do not approve of sacrifices for I do not care for happiness which is sought at the price of others suffering.

It is true that the Upanishads also subordinate that sacrificial piety to the spiritual religion which they formulated but they did not attack it in the way in which the Buddha did. The Buddha’s main object was to bring about a reformation in religious practices and a return to the basis principles. All those who adhere to the essential framework of the Hindu religion and attempt to bring it into conformity with the voice of awakened conscience are treated as avataras. It is an accepted view of the Hindu that the supreme as Vishnu assumed different forms to accomplish different purpose for the good of mankind. The Buddha was accepted as an avatara who reclaimed Hindus from sanguinary rites and erroneous practices and purified their religion of the numerous abuses which had crept into it. This avatara doctrine helps us to retain the faith of the ancestors while effecting reforms in it. Our Puranas describe the Buddha as the ninth avatara of Vishnu.

In Jayadeva’s ashtapadi (of the Gitagovinda) he refers to the different avataras and mentions the Buddha as an avatara of Vishnu and gives the following account.

where the slaughter of cattle is taught O Kesava,

you in the form of the Buddha victory to you, Hari lord of the world.

The commentator writes

nindsi na to sarvam ity arthah

The Buddha does not condemn the whole Sruti but only that part of it which enjoins sacrifices.

Jayadeva sums up the ten avataras in the next verse.

Who upheld the Vedas supported the universe

bore up the world destroyed the demons deceived

Bali broke the force of the ksatryas

conquered Ravana made the plough spread mercy

prevailed over aliens homage O Krisna

The commentator writes.

The Buddha utilized the Hindu inheritance to correct some of its expressions. He came to fulfill not to destroy. For us in this country the Buddha is an outstanding representative of our religious tradition. He left his footprint on the soil of India and his mark on the soul of the country with its habits and convictions. While the teaching of the Buddha it has entered into and become an integral part of our culture. The Brahmins and the Sramanhas were treated alike by the Buddha and the two traditions gradually blended. In a sense the Buddha is a maker modern Hinduism

Occasionally humanity after an infinite number of groping creates itself realizes the purpose of its existence in one great character and then again loses itself in the all too slow process of dissolution. The Buddha aimed at the development of a new type of free man free from prejudices intent on working out his own future with reliance on one’s own self attadipa. His humanism crossed racial and national barriers. Yet the chaotic condition of world affairs reflects the chaos in men’s souls. History has become universal in spirit. Its subject matter is neither Europe nor Asia neither East nor West but humanity it all lands and ages. In spite of political division the world is one whether we like it our not. The fortunes of everyone are linked up with those of others. But we are suffering from an exhaustion of spirit an increase of egoism individual and collective which seem to make the ideal of a world society too difficult to desire. What we need today is a spiritual view of the universe for which this country in spite of all its blunder and follies has stood which may blow through life again bursting the doors and flinging open the shutters of men’s life. We must recover the lost ideal of spiritual freedom. If we wish to achieve peace we must maintain that inner harmony that poise of the soul which are the essential elements of peace. We must possess ourselves though all else be lost. The free spirit sets no bounds to its love recognizes in all human beings a spark of the divine and offers itself up a willing victim to the cause of mankind. It casts of all fear except that of wrong doing passes the bounds of time and death and finds inexhaustible power in life eternal.

| I. | India and Buddhism- P.V. Bapat | 1-7 |

| II. | Origin of Buddhism - P.L. Vaidya | 8-17 |

| III. | Life and Teaching - C.V. Joshi | 18-30 |

| IV. | Four Buddhist Councils- B. Jinananda | 31-38 |

| The First Council | 31 | |

| The Second Council | 36 | |

| The Third Council | 39 | |

| The Fourth Council | 41 | |

| Appendix I | 44 | |

| Appendix II | 45 | |

| Appendix III | 46 | |

| V | Ashoka and the Expansion of Buddhism | 49-81 |

| I. Ashoka – P. V. Bapat | 49 | |

| II. Expansion of Buddhism | ||

| A. In India P.C. Bagchi | 52 | |

| B. In Northern Countries | ||

| Central Asia and China- P.C. Bagchi | 56 | |

| Korea and Japan -N. Takasaki | 59 | |

| Tibet (Central) and Ladakh – V.V.Gokhale | 63 | |

| Nepal –V.V Gokhale | 70 | |

| C. In southern Countries – R.C Majumdar | 72-81 | |

| Ceylon | 72 | |

| Burma | 73 | |

| The Malay Peninsula | 75 | |

| Siam (Thailand) | 76 | |

| Kambuja (Cambodia) | 77 | |

| Campa(Viet-Nam) | 78 | |

| Indonesia | 79 | |

| VI | Principal Schools and sects of Buddhism | 82-115 |

| A. In India | 82 | |

| The Sthaviravadins or | 85 | |

| The Theravadins | ||

| The Mahisasakas | 87 | |

| The Sarvastivadins | 88 | |

| The Haimavatas | 90 | |

| The Vatsiputtriyas | 90 | |

| The Dharmaguptikas | 91 | |

| The Kasyapiyas | 91 | |

| The Sautrantikas or the Sankrantivadins | 91 | |

| The Mahasnaghikas | 92 | |

| The Bahusrutiyas | 97 | |

| The Caityakas | 99 | |

| The madhyamika School | 101 | |

| The Yogacara School | 102 | |

| B. In Northern Countries | ||

| Tibet and Nepal –V.V. Gokhale | 104 | |

| China – G. H Sasaki | 104 | |

| The Chan (Dhyana) School | 105 | |

| The Vinaya School | 106 | |

| The Tantra School | 106 | |

| The Vijnanvada School | 107 | |

| The Sukhvatiyuha School | 107 | |

| The Avatamsaka School | 107 | |

| The Madhyamika School | 108 | |

| The T’ient-t’ai School | 109 | |

| Japan | 110 | |

| The Tendai Sect | 110 | |

| The Shingon Sect | 110 | |

| Pure Land Buddhism | 111 | |

| Zen Buddhism | 112 | |

| The Nichiren Sect | 113 | |

| C. In Southern Countries | 114 | |

| Ceylon | 114 | |

| Burma | 114 | |

| Thailand and Cambodia | 115 | |

| VII | Buddhist Literature | 116-147 |

| General – P.V. Bapat | 116 | |

| Survey of Important Books in pali and Buddhist Sanskrit | 119 | |

| I. Biographies – Nalinaksha dutt | 120 | |

| 1. The Mahavastu | 122 | |

| 2. The Nidanakatha | 124 | |

| II. The Buddha Teachings | ||

| 1. The Pali Sutta-Pitaka | 127 | |

| a. The Digha-nikaya | 128 | |

| b. The Dhammapada | 131 | |

| 2. The Sanskrit saddharma Pundrika | 133 | |

| III The Buddha’s Discipline Code | 136-147 | |

| Vinayaka- Pitaka | 136 | |

| 1. The patimokha-sutta | 137 | |

| 2.The Sutta-vibhanga | 138 | |

| 3 The Bhikkhuni-vibhanga | 140 | |

| 4. The Khandhakas | 142 | |

| VIII | Buddhist Education –S.Dutt | 148-162 |

| The Begninig | ||

| The Training of a Monk | 149 | |

| Monasteries as Seats of Learning | ||

| The intellectual Bias | 152 | |

| Maintenance and Endowment | 153 | |

| Chinese Pilgrims and their testimony | 154 | |

| Monastic Universities | ||

| Nalanda and Valabhi | 155 | |

| Vikramasila | 159 | |

| Jagaddala and Odantapuri | 160 | |

| Conclusion | 161 | |

| IX | Some Great Buddhist After Ashoka | 163-213 |

| A. In India | ||

| Rulers Menander Kanoshka Harsa -Bharat Singh Upadhyaya | 163 | |

| Pali Authors: nagasena Buddhadatta Buddhaghosa and dharmapala | 172 | |

| Sanskrit Authors: Asvaghosa, nagarjuna buddhapalita and Bhavaviveka Asanga and Vasubandhu, Dinnaga and Dhar-makirti | 183 | |

| B. In Tibet | ||

| Acarya Dipankara Srinana | 189 | |

| C. In China – G.h Sasaki | 199 | |

| Kumarajiva | 199 | |

| Paramartha | 201 | |

| Bodhidharma | 203 | |

| Yuan Chwang | 205 | |

| Bodhiruci | 208 | |

| D. In Japan | 209 | |

| D. In Japan | 209 | |

| Kukai | 210 | |

| Shinran | 210 | |

| Dogen | 210 | |

| Nichiren | 211 | |

| Appendix | ||

| List 1 | 212 | |

| List 2 | 213 | |

| X | Chinese Travelers – K.A. Nilakanta Sastri | 214-231 |

| Fa-hien | 214 | |

| Yuan Chwang | 220 | |

| I-tsing | 229 | |

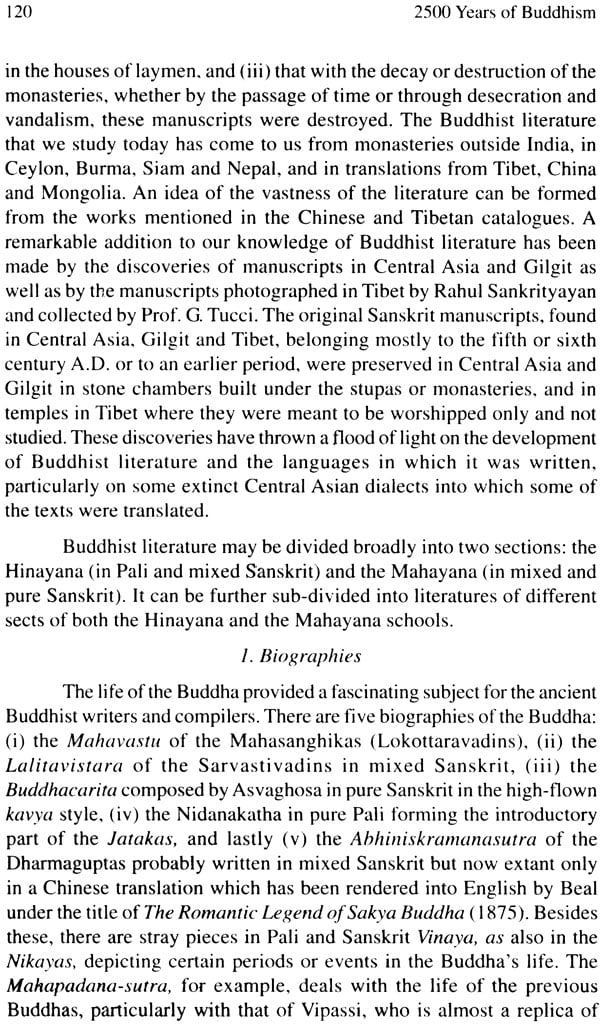

| XI | A Brief Survey of Buddhist Art | 232-257 |

| A. In India- T.N Ramachandran | 232 | |

| The Stupa in Buddhist Art | 233 | |

| Sculpture and Bronze | 237 | |

| Painting | 241 | |

| B. In other Asian Countries | 242 | |

| XII | Places of Buddhist interest | 258-283 |

| A. In Northern India – S.K.Saraswati | 258 | |

| B. In western India – D.B Diskalkar | 273 | |

| C. In Southern India -D.B Diskalkar | 280 | |

| XIII | Later Modifications of Buddhism | 284-318 |

| Approach to Hinduism –N. Aiyaswami Sastri | 284 | |

| Tantric Buddhism | 299 | |

| mantrayana and Sahajayana | 314 | |

| XIV | Buddhist Studies in Recent Times | 319-369 |

| Some eminent Buddhist Scholars | ||

| In India and Europe | 319 | |

| In China -P.V. Bapat | 331 | |

| In Japan | 332 | |

| Progress of Buddhist Studies | 334 | |

| In Europe and America –U.N. Ghosal | 334 | |

| In the East | ||

| 1. India | 344 | |

| 2. Ceylon | 353 | |

| 3. Burma | 357 | |

| 4. Thailand | 358 | |

| 5. Cambodia | 359 | |

| 6. Laos | 360 | |

| 7. Viet-nam | 362 | |

| 8. China | 363 | |

| 9. Japan | 365 | |

| XV | Buddhism in the Modern World | 370-395 |

| A. Cultural and political implications | 370 | |

| B. Revival of Buddhism The Maha Bodhi Society | 389 | |

| XVI | In Retrospect –P.V. Bapat | 396-399 |

| Glossary | 400-401 | |

| Bibliography | 402-405 | |

| Index | 407 | |

| Charts Maps and Illustrations |