Chhattisgarh Megaliths

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAR710 |

| Author: | A.K. Sharma |

| Publisher: | B.R. Publishing Corporation |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9789386223791 |

| Pages: | 154 (Throughout B/W and Color 14 Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.50 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 700 gm |

Book Description

It was in Megalithic times that the whole country of India was united by one culture i.e. Megalithic. Attempt has been made to give a vivid description of excavations conducted in different parts., About the development of Megalithic culture in Chhattisgarh all the surveyed and excavated sites have been described. The culture is still alive in Bastar amongst the Adivasis who along with executing mini-menhirs, now erect wooden menhirs with beautiful folk-art decorations Traditions never die.

A. K. Sharma is worldwide known for his inventive contributions in the field of Archaeology. During his 33 years of active career in ASI, he explored and excavated in Jammu and Kashmir, Uttaranchal, North-East India, Madhya Pradesh, Lakshadweep, Maharashtra, Gujrat, Rajasthan, Goa, Haryana, Chbattisgarh and other remote areas. After retirement from ASI he was appointed as OSD in IGNCA to excavate Jhiri with French team. His all excavation reports (22 Books) have been published. He has edited Purasatana, Puraprakash, Purajagat and is editor of Puramanthan, yearly magazine on recent advances in Archaeology. He has established Archaeological Museums at Mansar and Maa Anandmayee smriti Museum at Kankhal (Haridwar). At present he is advisor to the Government of Chhattisgarh and Member of Standing Committee of Central Advisory Board of Archaeology. He is directing excavations at Rajim in Chhattisgarh.

Chhattisgarh regions was originally known as `Dakshin Koshal' or `Mahakoshar from 600 B.C. to 1700 A.D. Kosala, literally means the 'land of treasure', and this has now been amply proved with the discovery of diamond, iron, manganese, coal, uranium, gold, lime-stone, etc. deposits in the region. It is virtually a land of treasure but now its resources are being exploited not much benefitting the simple, innocent inhabitants of the region.

The area having plenty of water, jungles, forest-produce, raw material and fertile soil was inhabited by man right from the Prehistoric times. During the Megalithic period the entire area was comparatively densely populated. The area formed part of Dandakarnya mentioned in the epic `Valmiki Ramayana', where the demon Dandak held his sway. Scholars like D.P. Mishra in his scholarly book 'The Search for Lanka', (1985), have tried to identify Dandakarnya as a part of Lanka. Bastar is the corrupt form of Vainsastahala, Kalidasa refers to it in his Meghaduta.

Chhattisgarh is the sacred land which was visited by Rama, Sita and Lakshmana. Ramayana informs us (III. 14) that Rama and Lakshmana saw Jatyu on a mountain while going to Panchavati. Prasravana has been identified with Abujmar in Bastar. Sivrinarayan (Sabarinarayana) in Bilaspur district is traditionally connected with Sabari who accorded welcome to Rama. Kahraud, near Sivrinarayana is said to be the place where Rama fought the Raksasas of the Janasthana; `Khara, Dausana' who were killed here hence kharaud. Later, Dandakarnya was ruled by the Nal Dynasty. The stone inscription extent in Podagarh (Koraput) bears testimony to this fact. The gold seals of this dynasty have also been found in `Adenga' village of Kondagaon tehsil in Baster. The Eastern Vakataka King Pravarasena I (C.A.D. 275-335) ruled over a portion of South Kosala or Chhattisgarh. During the reign of Pravarasena II's son Narendrasena (C. 455 -480 A.D.) Vidarbha was invaded by the Nala king Bhavadattavarman who was then ruling over Bastar region. He occupied Nandivardhan near Ramtek. In the emergency the Vakatakas had to shift their capital to Padmapura. A fragmentary inscription which was proposed to be issued from Padamapur has been discovered at village of Mohlai near Durg.

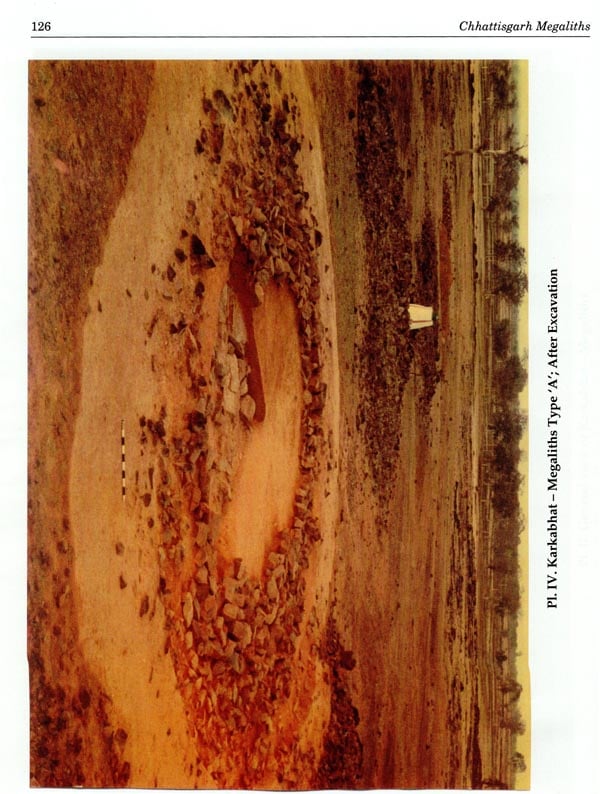

Having immense history behind it, Chhattisgarh is one of the most neglected areas in India. I am a Chhattisgarhi and as a part of my duty to my native land and as a tribute to the emergence of State of Chhattisgarh; through this book I am trying to bring out the neglected prehistory of the region during Megalithic times. In this book I have included the report of my excavations at Karkabhat in Balod district, which I conducted on behalf of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1990-91, for which I am grateful to the organization.

During the course of my investigations in Chhattisgarh as a senior fellow of Indian Council of Historical Research, I could collect a lot of data regarding Megalithic Culture, which I am using here. I am deeply beholden to the authorities of ICHR.

I am grateful to my colleagues in the Prehistory Branch of A.S.I., Nagpur S/Shri S.B. Ota, S.K. Lekhwani, S.S. Gupta, N.G. Nikose and R.S. Rana, who helped me in the excavations. I am also thankful to S/Shri J.S. Dubey, Dr. K.M. Girhe, P.K. Dwivedi and Lal Singh for the figures. The photographs are by S/Shri Pyara Singh, N.K. Nimje and R.S. Rana. To them I am deeply beholden. I am also grateful to S/Shri C.L. Yadav, P.V. Janardhanan, P.S. Pashine, Smt. K.V. Rao, R.G. Katole, T.B. Pashine, R.G. Katole, T.B. Thapa and R.S. Sharma for their ungrudging help. Shri Purshottam drove us, all over Chhattisgarh, without any break downs. To him I am thankful. Report on iron objects has been kindly contributed by Shri S.S. Gupta.

Illustrations are by courtesy Archaeological Survey of India, the organization which taught me archaeology and what I am today is due to the blessings of this organization. I express my gratitude.

I will not forget the simple, innocent, hardworking, honest Chhattisgarhi workers who made our excavations successful and popular.

I hope with the formation of Chhattisgarh State, the much neglected subject of archaeology will get impetus. Site like Malhar, Kharaud, Narayanpal, Pirda, Rajim, Laphagarh and scores of others will experience the archaeologists dig to unravel the treasure of history hidden in them. Let Chhattisgarh be remembered as the worthy part of our great Nation and let her inhabitants be like the Sun in shine; like Fire in brilliance; like Wind in power; like Soma in fragrance; like Lord Brahaspati in intellect; like the Asvins in beauty; like Indra Agni in strength (Mantra Brahman).

The term Megalithic was originally introduced by antiquarians to describe a fairly easily definable class of monuments in Western and Northern Europe, consisting of huge, undressed stones and termed as Celtic dolmens, cromlechs and menhirs. It has subsequently been extended to cover a far more miscellaneous collection of erections and even excavations all over the Old World and into the new.

The researches on the megalithic monuments in India go back to 1823 when Babington brought out his "Description of the Pandoo Coolies of Malabar" in the Transactions of the Literary Society of Bombay.In the west the interest in the study of such monuments could be seen hinted in the publication of J. Ferguson.3 A reference to the distinctive nature of Indian megalith was donated by Vanstaveen in his "Note on the Antiquities found in the parts of the Upper Godavari'. Later publications were Jagor's excavation report on the stone burials site of Adichennalur and Perumbiar in 1915; J.W. Breek's Account of Primitive tribes and monuments of the Neelgiris, London, 1873 and Foote's 'Catalogue of Prehistoric Antiquities, Madras, Govt. Museum, Madras, 1901.

In Indian, sub-continent though Peninsular India has long been known to contain a large number of megalithic structures of varied types belonging to the early Iron Age, they now encompass almost whole of the Indian sub-continent right from Baluchistan and Baluchi and Parsian Makran, Waghadu Shah Billawal and Murad Memon (the last three within a radius of 32 km of Karachi) to Manipur (Salanghel 65 km from Imphal)and from Leh valley of Ladakh, Burzahom, Gufkral, etc. in Kashmir valley to Pudukkotai in down south. Despite structural or regional disparities, they share a common cultural equipment, including the wide spread influence of a single technological tradition.5 Right from Bastar in Chhattisgarh to Manipur in North-East India through Hazaribagh and Singhbhum districts of Bihar megaliths are a living tradition of the aborigines, which according to many scholars, has affinity with the south-east Asiatic tradition. Prevalence of Megalithic culture in East Asian countries is well attested by the evidences of Menhirs in north Japan, South Korea and Java, dolmens, dolmenoid cists and cap-stones in north-east and east China, South-Korea, North-Korea, Malaysia, Java and Japan. Their striking similarity with those of their Indian counterparts point out towards cultural link in the distant past. They are mostly commemorative rather than sepulchral. The Maria Gonds of Bastar,6 the Bonds and Godabas of Orissa,? the Oraons and Mundas of Chota Nagpur,8 the Khasis of Meghalaya and the Nagas of Nagaland9 and Manipur and the Todas10 of Nilgiris still erect dolmens, stone circles and menhirs. Broadly speaking megalithic monuments of some kind or the other are found over different parts of India, while the living tradition is restricted to eastern India, the ancient tradition, along with various trends and modification is confined to the south.

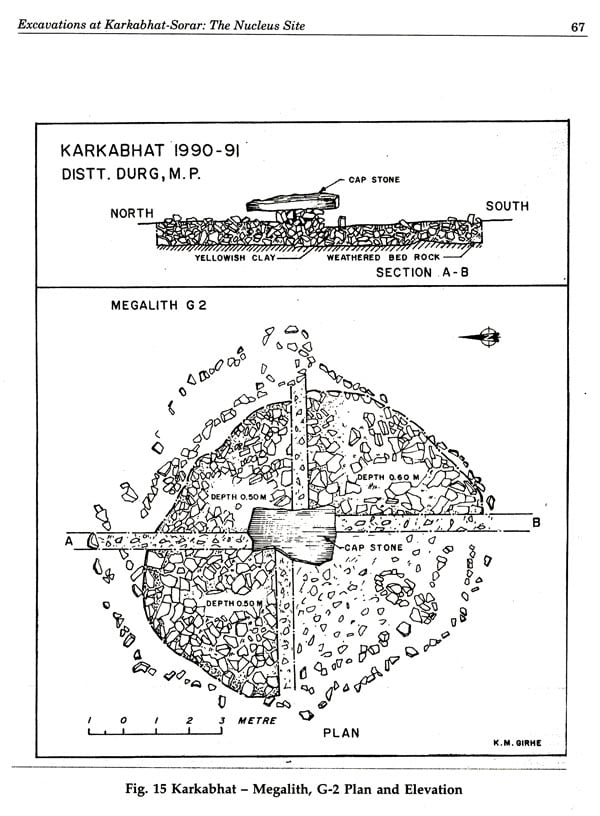

With the recent discoveries and excavations in far flung areas like Almora12 and Kashmir,13,14 it now appears that with the spread of Megalithic culture, it was from the second half of second millennium B.C. that the Indian sub-continent was for the first time more culturally united. As per evidence, megalithic people are known for growing rice and smelting of iron, the later for the first time in our sub-continent. The earlier lacunae of paucity of habitation sites of megalithic people has now been removed with the excavations at Burzahom, Gufkral in Jammu and Kashmir, Naikund in Vidarbha region of Maharashtra and Karkabhat in Chhattisgarh region of Chhattisgarh where sufficient habitation deposits have been located and exposed, revealing the structural and other remains of megalithic people.

They selected such spots for their habitation and erection or excavation of burials where like iron, copper and gold bearing deposits were available. Generally they chose higher rock bench area with thin soil cover with monsoon fed lateritic areas for the erection of megalithic burials and memorials. Investigations of the soil regions of the Megalithic (both burial and habitation) areas in Peninsular India and Sri Lanka indicate that they are represented by three types of soil, i.e. yellowish brown, dark greyish brown and red gravel that are suitable for wet agriculture due to low water retention (high sand content does not encourage water retention), low willing point (as a consequence of low water retention willing point is reached fairly rapidly and high acidity of soil - during the rainy season minerals such as ferrous, magnesium and sodium are leached out to a lower horizon. Under drier conditions these minerals surface and get deposited at the vary upper horizons. The PH value of this soil type is lower than.

It suggests that the Early Iron Age people selected these soil type areas which are unsuitable for agricultural purposes, for erection of megaliths.