The Collected Works of Sri Ramana Maharshi

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDL164 |

| Author: | SRI RAMANASRAMAM TIRUVANNAMALAI |

| Publisher: | Sri Ramanasramam, Tamil Nadu |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2023 |

| ISBN: | 9788188018062 |

| Pages: | 336 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5” X 5.5” |

| Weight | 370 gm |

Book Description

Publisher’s Note

Editions prior to the sixth edition of this book contain the text (introduction and translations from Tamil) of Arthur Osborne’s original version.

After thoughtful consideration, beginning with the sixth edition, some of the translations were replaced by those of other eminent devotees, like Prof. K. Swaminathan’s, whose scholarship and devotion have endowed them with insight into the subtleties of the Tamil language. However, the bulk of the translations still remain Arthur Osborne’s.

In the previous edition, Dr. H. Ramamurthy’s translation of Sarvajnanottaram was incorporated along with an Appendix, containing a translation of Sri T. K. Sundaresa Iyer’s Preface to the Tamil original (Sri Ramana Nool Thirattu) of Collected Works.

In this ninth edition, besides some general correction, two works translated by Sri Bhagavan have been included. They are “Na Karmana,” and “The Heart and Brain”. We have also added more information regarding the genesis of certain verses that Sri Bhagavan wrote or translated.

Preface

When the Maharshi, Bhagavan Sri Ramana, realized the Self, he was a lad in his seventeenth year, belonging to a middle class Brahmin family of South India. He was still going to high school and had undergone no spiritual training and learnt nothing of spiritual philosophy. Normally some study is needed, followed by long and arduous training, often lasting a whole lifetime more often still incomplete at the end of a lifetime. As the sages say, it depends on the spiritual maturity of a person. It can be compared to a pilgrimage, and a day’s journey on it to a lifetime; a person’s attaining the goal, or how near he comes to it, will depend partly on the energy with which he presses forward and partly on the distance from it at which he wakes up and begins his day’s journey. Only in the rarest cases is it possible, as with the Maharshi, to take a single step and the goal is reached.

To say that the Maharshi realized the Self does not mean that he understood any new doctrine or theory or achieved any higher state or miraculous powers, but that the ‘I’ who understands or does not understand doctrine and who possesses or does not possess powers, became consciously identical with the Atman, the universal Self or Spirit. The Maharshi himself has described in simple, picturesque language how this happened.

“It was about six weeks before I left Madura for good that the great change in my life took place. It was quite sudden. I was sitting along in a room on the first floor of my uncle’s house. I seldom had any sickness, and on that day there was nothing wrong with my health, but a sudden violent fear of death overtook me. There was nothing in my state of health to account for it, and I did not try to account for it or to find out whether there was any reason for the fear. I just felt ‘I am going to die’ and began thinking what to do about it. It did not occur to me to consult a doctor or my elders or friends; I felt that I had to solve the problem myself, there and then.

“The shock of the fear of death drove my mind inwards and I said to myself mentally, without actually framing the words: ‘Now death has come; what does it mean? What is it that is dying? This body dies.’ And I at once dramatized the occurrence of death. I lay with my limbs stretched out stiff, as though rigor mortis had set in, and imitated a corpse so as to give greater reality to the enquiry. I held my breath and kept my lips tightly closed so that no sound could escape, so that neither the word ‘I’ nor any other word could be uttered. ‘Well then,’ I said to myself, ‘this body is dead. It will be carried stiff to the burning ground and there burnt and reduced to ashes. But with the death of this body am I dead? Is the body i? It is silent and inert but I feel the full force of my personality and even the voice of the ‘I’ within me, apart from it. So I am Spirit transcending the body. The body dies but the Spirit transcending it cannot be touched by death. That means I am the deathless Spirit.’ All this was not dull thought; it flashed through me vividly as living truth which I perceived directly, almost without thought-process. ‘I’ was something very real, thing about my present state, and all the conscious activity connected with my body was centred on that ‘I’. From itself by a powerful fascination. Fear of death had vanished once and for all. Absorption in the Self continued unbroken from that time on. Other thoughts might come and go like the various notes of music, but the ‘I’ continued like the fundamental sruti note that underlies and blends with all the other notes. Whether the body was engaged in talking, reading, or anything else, I was still centred on ‘I’. Previous to that crisis I had no clear perception of my Self and was not consciously attracted to it. I felt no perceptible or direct interest in it, much less any inclination to dwell permanently in it.”

Such an experience of identity does not always, or even normally, result in liberation. It comes to a seeker but the inherent tendencies of the ego cloud it over again. Thenceforward he has the memory, the indubitable certainty, of the true state, but he does not live in it permanently. He has to strive to purify the mind and attain complete submission so that there are no tendencies to pull him back again to the illusion of limited separative being. However, the Self-oblivious ego, even when once made aware of the Self, does not get liberation, that is, Self-realization, on account of the obstruction of accumulated mental tendencies. It frequently confuses the body with the Self, forgetting that it is itself, in truth, the Self. The miracle was that in the Maharshi’s case there was no clouding over, no relapse into ignorance; he remained from then on in constant awareness of identity with the one Self.

For a few weeks after this awakening he remained with his family, leading outwardly the life of a schoolboy, although all outer values had lost their meaning for him. He no longer cared what he ate, accepting with like indifference whatever was offered. He no longer stood up for his rights or interested himself in boyish activities. In so far as it was possible he conformed to the conditions of life and concealed his new state of consciousness, but his elders saw his lack of interest in learning and all worldly activities, and resented it.

There are many holy places in India, representing different modes of spirituality and different types of paths. The holy hill of Arunachala with the town of Tiruvannamalai at its foot, is supreme among them, in that it is the centre of the direct path of Self-enquiry guided by the silent influence of the Guru upon the Heart of the devotee, the secret and sacred Heart-centre of Siva, wherein He always abides as a Siddha (great one).

It is the seat of Siva who, identified as Dakshinamurti, teaches in silence as was exemplified in the life of Bhagavan.

It is the centre and the path where physical contact with the Guru is not necessary, but the silent teaching speaks direct to the Heart. Even before his Realization it had thrilled the Maharshi and drawn him like a magnet.

“Hearken; It stands as an insentient Hill. Its action is mysterious, past human understanding. From the age of innocence it had shone within my mind that Arunachala was something of surpassing grandeur but even when I came to know through another that it was the same as Tiruvannamalai I did not realize its meanings. When it drew me up to it, stilling my mind, and I came close, I saw it (stand) unmoving.

Now, seeing that his elders resented his living like a sadhu while enjoying the benefits of home life, he secretly left home and went as a sadhu to Tiruvannamalai. He never left there again. He remained for more than fifty years as Dakshinamurti, teaching the path of Self-enquiry to all who came, from India and abroad, from East and West. An ashram grew up around him. His name of Venkataraman was shortened to Ramana, and he was also called the Maharshi, that is the Maha Rishi or great sage, a title traditionally given to one who inaugurates a new spiritual path. However, his devotees mostly spoke of him as Bhagavan. In speaking to him they also addressed him in the third person as Bhagavan. Self-realization means constant conscious awareness of identity with Atman, the Absolute, the Spirit, the Self of all; it is the state which Christ expressed when he said: “I and my Father are One.” This is a very rare thing. Such a one is habitually addressed as Bhagavan, which is a word meaning ‘God’

On Bhagavan’s first arrival at Tiruvannamalai there was no question of disciples or teaching. He discarded even apparent interest in the manifested world, sitting immersed in that experience of Being which is integral Knowledge and ineffable Bliss, beyond life and death. He was indifferent to whether the body continued to live, and made no effort to sustain it. Others sustained it by bringing him daily the cup of food that was needed for its nourishment; and when he began to return gradually to a participation in the activities of life it was for the spiritual sustenance of those who had gathered around him.

The same applies also to his study of philosophy. He did not need the mind’s confirmation of the resplendent Reality in which he was established, only his followers required explanations. It began with Palaniswami, a Malayali attendant who had access to books of spiritual philosophy only in Tamil. He had great difficulty in reading Tamil, so the Maharshi read the books for him and expounded their essential meaning Similarly he read other books for other devotees and became erudite without seeking or valuing erudition.

There was no change or development in his philosophy during the more than half a century of his teaching. There could be none, since he had not worked out any philosophy but merely recognized the expositions of transcendental truth in theory, myth, and symbol when he read them. what he taught was the ultimate doctrine of non-duality, or advaita, in which all other doctrines are finally absorbed: that Being is One and is manifested in the universe and in all creatures without ever changing from its eternal, unmanifest Self, much as, in a dream, the mind creates all the people and events a man sees, without losing anything by their creation or gaining anything by their re-absorption, without ceasing to be itself.

Some found this hard to believe, taking it to imply that the world was unreal, but the Maharshi explained to them that the world was only unreal as world, that is to say as a separate, self-subsistent thing, but was real as a manifestation of the Self, just as the events one sees on a cinema screen are unreal as actual life but real as a shadow-show. Some feared that it denied the existence of a personal god to whom they could pray, but it transcends this doctrine without denying it, for ultimately the worshipper is absorbed back into union with the worshipped. The man who prays, the prayer, and the God to whom he prays all have reality only as manifestations of the Self.

Just as the Maharshi realized the Self with no previous theoretical instruction, so he attached little importance to theory in training his disciples. The theory expounded in the following works is all turned to the practical purpose of helping the reader towards Self-knowledge-by which is not meant any psychological study but knowing and being the Self which exists behind the ego or mind. Questions that were asked for mere gratification of curiosity he would brush aside. If asked about the posthumous state of man he might answer: “Why do you want to know what you will be when you die before you know what you are now? First find out what you are now.” Thus he was turning the questioner from mental curiosity to the spiritual quest. Similarly he would parry questions about Samadhi or about the state of the jnani (the Self-realized man): “Why do you want to know about the jnani before you know about yourself? First find out who you are.” But when questions bore upon the task of self-discovery he had enormous patience in explaining it.

The method of enquiry into oneself that he taught goes beyond philosophy and beyond psychology, for it is not the qualities of the ego that are sought, but the Self standing resplendent without qualities when the ego ceases to function. What the mind has to do is not to suggest a reply, but to remain quiet so that the true reply can arise. “It is not right to make an incantation of ‘Who am i?’. Put the question only once and then concentrate on finding the source of the ego and preventing the occurrence of thoughts.” ‘Finding the source of the ego,’ implies concentration on the spiritual centre in the body, the Heart on the right side, as explained by the Maharshi. And, so concentrating, ‘to prevent the occurrence of thought’. “Suggestive replies to the enquiry, such as ‘I am Siva’, are not to be given to the mind during meditation. The true answer will come of itself. No answer the ego can give can be right. These affirmations or auto suggestions may be of help to those who follow other methods but not in this method of enquiry. If you keep on asking the reply will come.” The reply comes as a current of awareness in the Heart, fitful at first and only achieved by intense effort, but gradually increasing in power and constancy, becoming more spontaneous, acting as a check on thoughts and actions, undermining the ego, until finally the ego disappears and the certitude of pure Consciousness remains.

As taught by the Maharshi, Self-enquiry embraces karma marga as well as jnana marga, the path of action as well as that of Knowledge, for it is to be used not only as a meditation but in the events of life, assailing the manifestations of egoism by asking to whom is good or bad fortune, triumph or disaster. In this way, the circumstances of life, far from being an obstacle to sadhana, are made an instrument of sadhana. Therefore those who asked whether they should renounce the life of the world were always discouraged from doing so. Instead they were enjoined to perform their duties in life without self-interest.

It embraces the path of love and devotion also. The Maharshi said: “There are two ways: either ask yourself, ‘Who am I?’ or submit.” On another occasion he said: “Submit to me and I will strike down the mind.” There were many who followed, through love, this path of submission to him. It led to the same goal. He said: “God, Guru, and Self are not really different but the same.” Those who followed the path of Self-enquiry were seeking the Self inwardly, whereas those who strove through love were submitting to the Guru manifested outwardly. But the two were the same. That is more than ever clear to his devotees now that the Maharshi has left the body and become the inner Guru in the Heart of each one of them.

It was thus a new and integral path that the Maharshi opened to those who turn to him. The ancient path of Self-enquiry was pure jnana marga to be followed in silent meditation by the hermit and had, moreover, been considered by the sages unsuited to this kaliyuga, this spiritually dark age in which we live. What Bhagavan did was not so much to restore the old path as to create a new one adapted to the conditions of our age, a path that can be followed in city or household no les than in forest or hermitage, with a period of meditation each day and constant remembering throughout the day’s activities, with or without the support of outer observances.

The Maharshi wrote very little. He taught mainly through the tremendous power of spiritual silence. That did not mean that he was unwilling to answer questions when asked. So long as he felt that they were asked with a sincere motive and not out of idle curiosity, he answered fully whether in speech or writing. However, it was the silent influence upon the Heart that was the essential teaching.

Nearly everything that he wrote was in response to some request, to meet the specific needs of some devotee, and therefore a short note is given at the beginning of the various items explaining their genesis. This is for the interest of the reader, but the particular need that evoked them does not in any way impair the universality of their scope.

It is to be noted that the verse items are not arranged in chronological order. They were arranged in order by Bhagavan himself, for a devotee who kept a private collection of them, and therefore the same order has been retained here.

A new work, Spiritual Instruction, published during Bhagavan’s time but not included in the first two editions, has now been included. A few small additions have also been made in the case of one or two works. They are found in the original Tamil versions published during Bhagavan’s time. They do not alter the sense of these works.

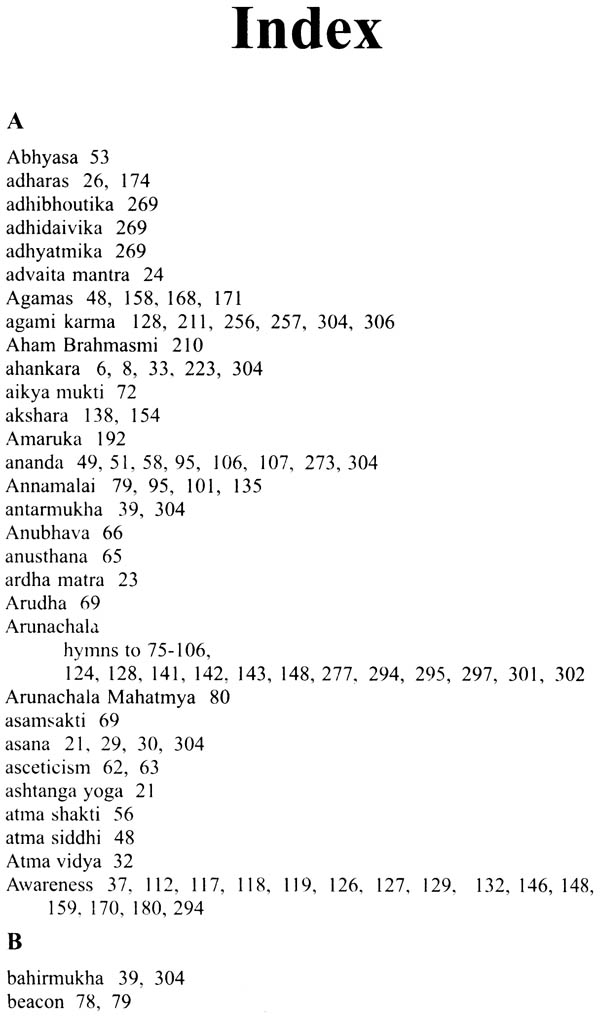

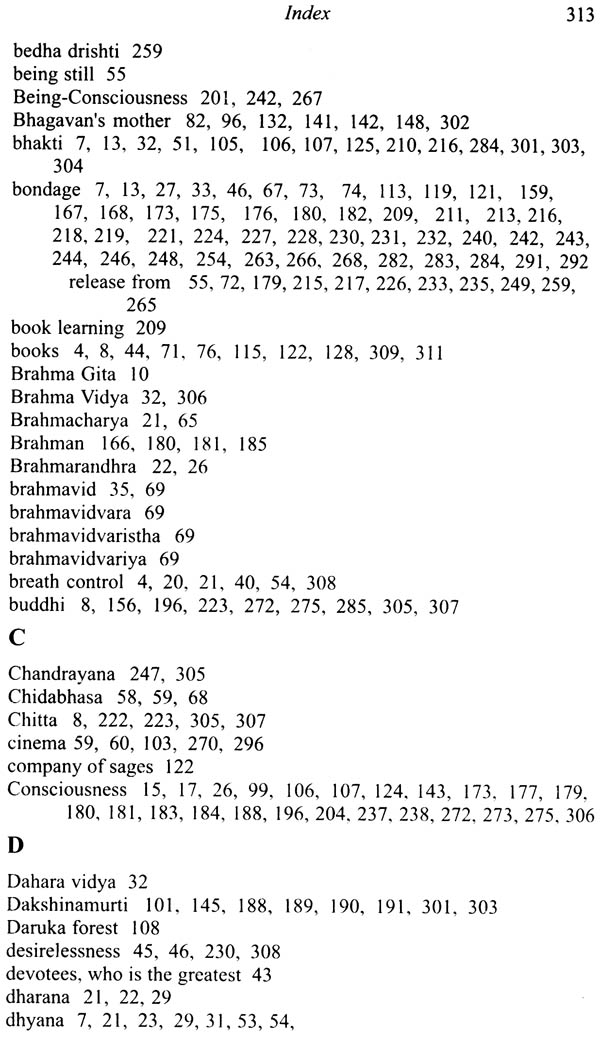

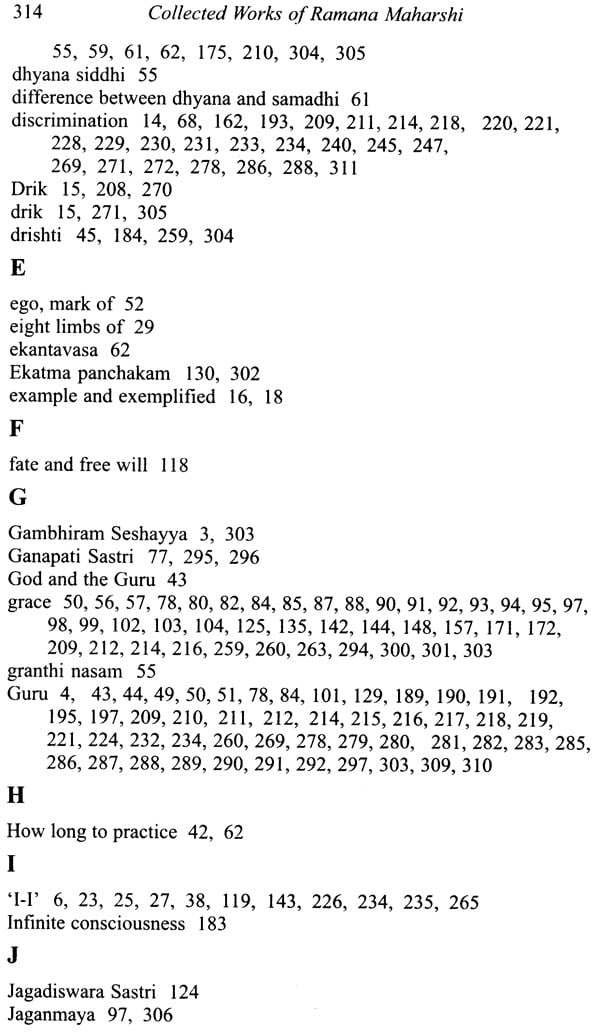

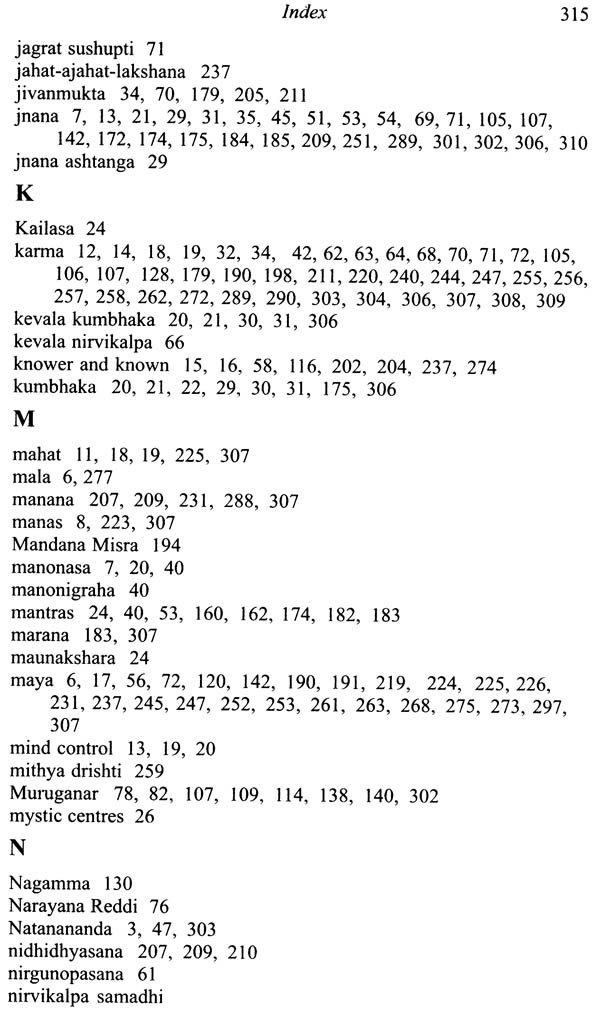

| Preface | ix | |

| PROSE | ||

| 1 | Self-enquiry | 3 |

| 2 | Who Am I? | 36 |

| 3 | Spiritual Instruction | 47 |

| | ||

| 4 | Five Hymns to Arunachala | 75 |

| Sri Arunachala Mahatmyam | 80 | |

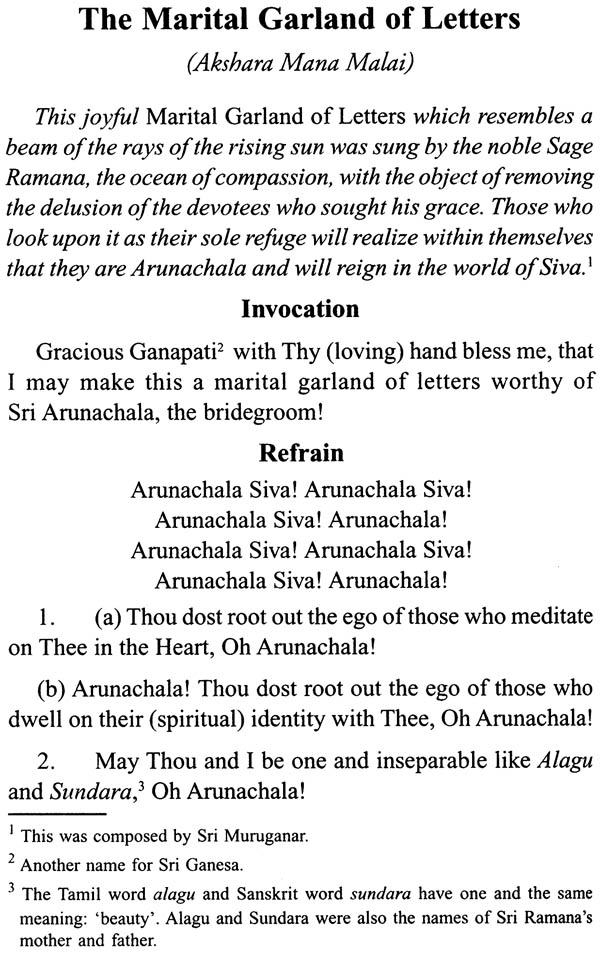

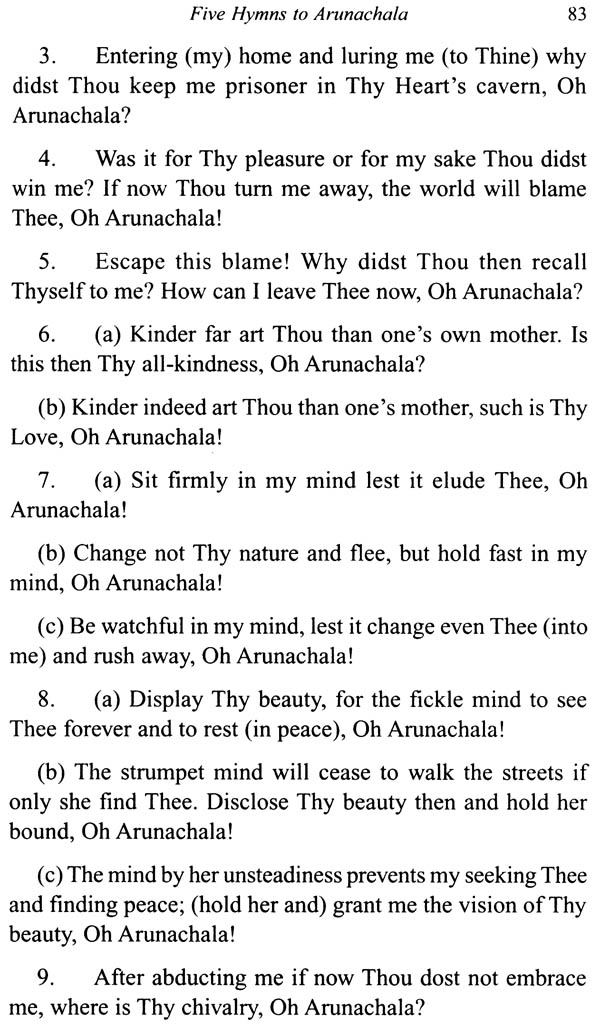

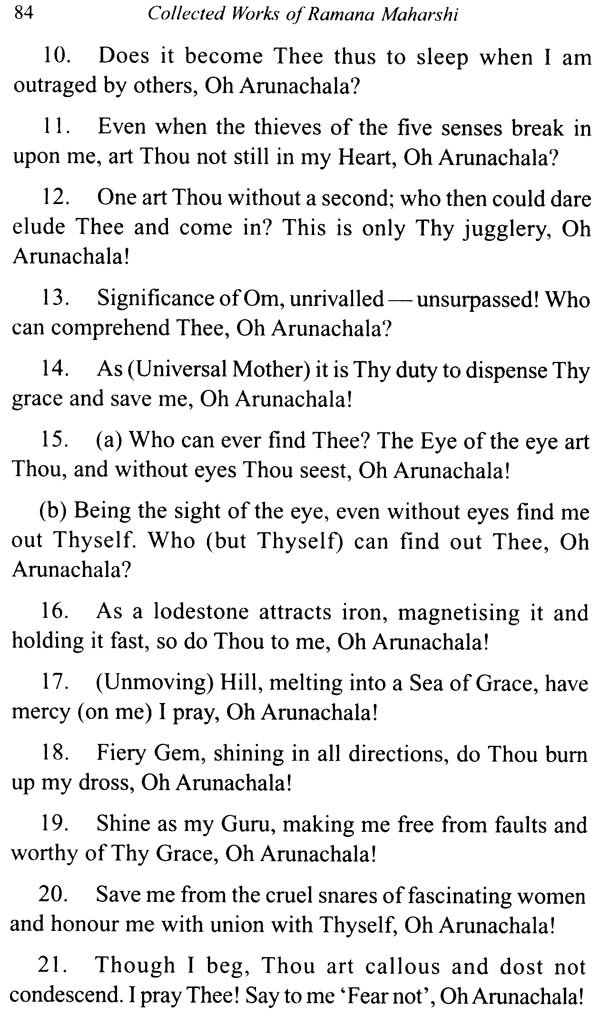

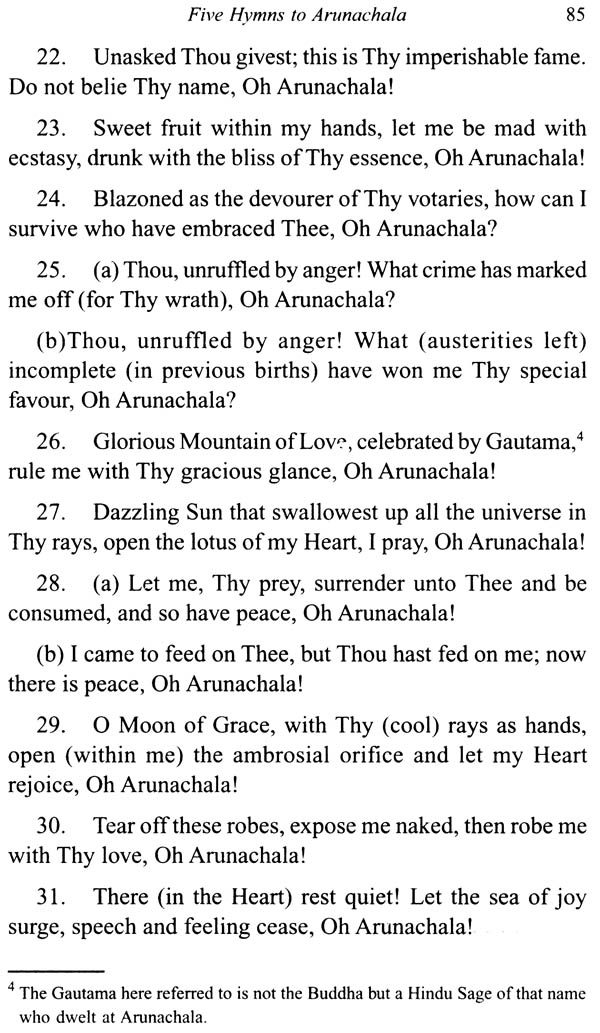

| The Marital Garland of Letters | 82 | |

| The Necklet of Nine Gems | 95 | |

| Eleven Verses to Sri Arunachala | 98 | |

| Eight Stanzas to Sri Arunachala | 101 | |

| Five Stanzas to Sri Arunachala | 104 | |

| 5 | The Essence of Instruction | 108 |

| 6 | Reality in Forty Verses | 114 |

| Reality in Forty Verses: Supplement | 122 | |

| 7 | Five Verses on the Self | 130 |

| 8 | Miscellaneous Verses | |

| The Song of the Poppadum | 132 | |

| Self-Knowledge | 134 | |

| Verses on the Celebration of Bhagavan’s Birthday | 136 | |

| Complaint of the Stomach | 137 | |

| Nine Stray Verses | 138 | |

| Apology to Hornets | 140 | |

| Reply to the Mother | 141 | |

| For the Mother’s Recovery | 142 | |

| Arunachala Ramana | 143 | |

| The Self in the Heart | 143 | |

| 9 | Occasional Verses | |

| Tiruchuzhi | 144 | |

| Hara and Uma | 144 | |

| Hometown and Parents | 145 | |

| Marks of Muruga | 145 | |

| On Subrahmanya | 146 | |

| Virupaksha Cave | 146 | |

| The Cow Lakshmi | 146 | |

| Ganesa | 147 | |

| Vishnu | 147 | |

| Dipavali | 147 | |

| Miracle of Dakshinamurti | 148 | |

| The Self | 148 | |

| Liberation | 148 | |

| Silence | 149 | |

| One Letter | 149 | |

| Sleep while Awake | 149 | |

| A Jnani and His Body | 149 | |

| | ||

| 10 | The Song Celestial | 153 |

| 11 | Translations from the Agamas | 158 |

| Atma Sakshatkara | 159 | |

| Devikalottara | 171 | |

| 12 | Translations from Shankaracharya | 187 |

| Dakshinamurti Stotra | 188 | |

| Guru Stuti | 192 | |

| Hastamalaka Stotra | 195 | |

| Atma Bodha | 198 | |

| Vivekachudamani | 208 | |

| Drik Drisya Viveka | 270 | |

| 13 | Other Translations | |

| Vichara Mani Mala | 277 | |

| From the Srimad Bhagavatam and Rama Gita | 293 | |

| He Who is Hara | 293 | |

| Ramana Ashtottara Satanamastotra | 294 | |

| Heart and the Brain | 295 | |

| Na Karmana | 297 | |

| Appendix | 299 | |

| Glossary | 304 | |

| Index | 312 | |

| Notes on Pronunciation | 319 |