The Complex Heritage of Early India (Essaya in Memory of R. S. Sharma)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAM966 |

| Author: | D. N. Jha |

| Publisher: | Manohar Publishers and Distributors |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| ISBN: | 9789350980583 |

| Pages: | 718 (16 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 9.0 inch X 6.0 inch |

| Weight | 1 kg |

Book Description

Professor Ram Sharan Sharma (d. 20 August 2011) was a trailblazer in the field of Indian historical research and has the unique distinction of changing its direction in post-independence India He made sharp departures from both colonial and chauvinist historiography, exploded the myth of a stagnant Indian society, shifted the focus of history writing from the chronicle of kings and queens to the history of the common people, especially the underprivileged and the marginalized, took Indian history away from the realm of myths and legends, and radically demystified it. He analysed the past through the prism of the present, championed the cause of scientific history and did not seek to gill the lily. The present volume seeks to perpetuate his memory and celebrate his contribution from which the subsequent generation has immensely benefited.

The essays brought together here deal with diverse themes and cover a wide canvas. They range from Harappan civilization, the Rigvedic chronology, and early historical archaeology to the history of urbanization, level of monetization, nature of trade, and to issues arising out of early medieval land grants, and of the aspects of early Indian material culture. The anthology also contains articles of seminal importance on the nature and ideology of the caste and gender inequality and social dimensions of earl Indian art. It bears the unmistakable stamp of R.S. Sharma’s perspectives on India’s past.

D.N. Jha was Professor of History at the University of Delhi until his retirement in 2005. He is the author of Revenue System in Post-Maurya and Gupta Times; Ancient India in Historical Outline; Early India: A Concise History; Holy Cow: Beef in Indian Dietary Traditions reprinted as the Myth of the Holy Cow and Rethinking Hindu Identity. His edited volumes include The Feudal Order: State, Society and Ideology in Early Medieval India; The Many Careers of D.O. Kosambi and Contesting Symbols and Stereotypes: Essays on Indian History and Culture. He was General President, Indian History Congress in 2006.

The death of Professor Ram Sharan Sharma on 11 August 2011 at the age of ninety-one caused an irreparable loss to the Indian academic world. A large number of historians over the years benefited from his academic leadership as well as from his insightful and path-breaking researches. Not surprisingly, soon after his passing away many of his friends, admirers and former students came together with the idea of publishing a volume in his memory and asked me to edit it. Requests for contribution drew such an overwhelming response from scholars that the articles received far exceeded the number that could be accommodated in a single volume. These have therefore been divided into two independent volumes, one containing -papers on the early period, called The Complex Heritage of Early India, and the other incorporating those on medieval, modern and contemporary history of India titled The Evolution of a Nation: Pre-Colonial to Post- Colonial.

Throughout the preparation of the two commemoration volumes, running into over 1400 printed pages in all, I was sustained in my endeavour by the cooperation and constant emotional support of the contributors. In this context I would like to make a special mention of the late Barun De who honoured his commitment and sent his reminiscences even as he lay on his death-bed fighting the terminal illness which ultimately took him away from us. These volumes dedicated to the memory of Professor R.S. Sharma is therefore touched by a further sadness at the passing away of his younger friend and professional colleague, Barun, with whom many of us shared a common world-view.

The volumes have been prepared for the press with minimum editorial intervention. The referencing styles of individual authors have been retained without much change, though, keeping in mind their preferences, effort has been made to standardize the use of diacritical marks as far as possible. Professors Irfan Habib, Shireen Moosvi, Eugenia Vanina, K.M. Shrimali and Amar Farooqui offered valuable advice, especially on the volume-wise division and arrangement of articles dealing with diverse themes. Professor Anjani Kumar Sinha shared with me his memories of R.S. Sharma and made constructive comments on my paper which forms the introduction to these volumes. Mr. Siddharth Chowdhury extended indispensable editorial help and guidance and Mr. Ramesh Jain provided the much needed logistical support to our effort and thus facilitated the expeditious publication of the volumes. My wife, Rajrani, has always been there to help me in many silent ways. I am grateful to all of them.

Engaging with R.S. Sharma and His Historiography

D.N.JHA

Born on 1 September 1920, Professor Ram Sharan Sharma (d. 20 August 2011) had his schooling in his village, Barauni, and at Begusarai, then a sub divisional town of Bihar. He joined Patna College in 1937 where he completed his Master’s in history in 1943. After a brief stint at H.D. Jain College, Arrah and T.N.B. College, Bhagalpur, he became a lecturer in Patna College. In 1958 he took over as head of the department of history, Patna University, which position he held until 1972 when he became the founder Chairman of the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR), New Delhi. In the following year he moved to the University of Delhi which offered him professorship and headship of its history department. At both Patna and Delhi he played a significant role in giving a radical direction to history teaching. Already at Patna University he had organized a national workshop in 1965-perhaps the first of its kind in the country-to prepare a blueprint for the secularization, radicalization and decolonization of the history syllabi and had implemented many of his ideas there.’ Soon after joining the University of Delhi in 1973, he convinced his colleagues in the Department of History and the undergraduate colleges, that curriculum revision, being linked with the ever increasing corpus of historical literature, should be a continuous process and create space for new interpretations of the past. With their support and cooperation he introduced drastic changes in the courses of study, and, inspired his successors who undertook similar exercise from time to time, often in the face of bitter opposition from the obscurantist and status quoist elements in the academic establishment and outside.

As an institution builder R.S. Sharma has few parallels. Both a Patna and Delhi universities he succeeded in expanding the history faculty by creating positions in new areas of historical research and making it academically active and vibrant. As the founder-chairman of the ICHR he created its infrastructure, initiated many project which involved historians from different parts of the country and gave a truly national character to its activities. The projects relating to the publication of historical sources, translation of standard book and monographs in English into Indian languages, preparation of an epigraphic dictionary, historiographical surveys of the various areas of Indian history and the compilation of records on the national movement (known as the ‘Towards Freedom’ project as opposed to the ‘Transfer of Power’ by Nicholas Mansergh who viewed Indian freedom struggle from the British point of view), were all initiated during his chairmanship, and have, over the years, influenced research and teaching. The priority he accorded to the demystification of history and its reconstruction on secular and scientific lines, despite being occasionally eclipsed by the communal and retrograde government policies, has remained prominent in the ICHR’s agenda. As an important member of the National Commission of the History of Sciences in India and of the UNESCO Commission on the History of Central Asian Civilizations he participated in the organization of the volumes published under their auspices. It was also largely because of his efforts that the largest body of professional Indian historians, the Indian History Congress, of which he was the General President in 1975, and which honoured him with H.K. Barpujari Award in 1987 and Y.K. Rajwade National Award in 2002 for his life-long service and contribution to historical studies, has become the symbol of secular and scientific approach to history. In whatever capacity R.S. Sharma worked, his role bore the stamp of the academic vision and world view he developed early in life.

In his youth R.S. Sharma, popularly known as R.S. among his friends and Sharmaji among his pupils, came in contact with several prominent personalities. One of them was the famous journalist, lawyer and social reformer, Sachidanand Sinha, the first president of the Constituent Assembly, in consultation with whom he prepared a report on the boundary dispute between Bihar and Bengal. But his association with Rahul Sankrityayan, the progressive polyglot and polymath who commanded respect of his contemporaries as well as the younger generation, Karyanand Sharma, who began his political career with Non-Coperation movement in 1920 and later emerged as an important leader of the peasant movement and the Communist Party of India, and with Swami Sahjanand Saraswati who founded the Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha in 1929 and became the first president of the All India Kisan Sabha in 1936 had a much deeper influence on him. Sharmaji shared with them some of his personality traits like his spartan way of life, disarming humility and unpretentiousness, and an unstated, albeit perceptible, aversion to elitism, and, above all, his unquestionable personal and academic integrity which, throughout his professional career, presented a sharp contrast to those who plagiarize and prosper in the academic world.

His simplicity and clarity of expression, reminiscent of Rahul Sankrityayan, was best reflected in his classroom lectures and in his writings which were all free of jargon; he never allowed his erudition to be overshadowed by obfuscation in the name of nuanced scholarship.

With these qualities, he could easily reach out to people from different walks of life; it was not an unusual sight to see him sitting on the Delhi University lawns and discussing with non-teaching staff their problems and, negotiating on their behalf in a situation of confrontation with the authorities.

Through his association with persons like Rahul Sankrityayan and Karyanand Sharma as well as several freedom fighters he also enriched his own firsthand knowledge of the hard realities of rural life and its trials and tribulations and naturally moved to Marxist ideology and came close to the undivided Communist Party of India, whose leadership often sought his advice. Unlike the historians who turned to Marxism in the late 1950s and early 1960s only to disown it after gaining academic legitimacy, Professor Sharma remained a Marxist throughout his life without drumbeating on Karl Marx. Far from being doctrinaire, his Marxism was pragmatic and pervades all his research work; there was nothing formulaic about his choice, and treatment of themes he wrote on. His aversion to the mechanical application of the ideas of Marx to the Indian situation is evident from his assessment of S.A Dange’s India from Primitive Communism to Slavery (1949) as more schematic than scholarly.

Professor Sharma began his research career soon after he joined teaching. His early writings drew attention to the dharmasastric evidence which sought to equate women with property and sudras and highlighted their subservient position and exploitation, thus anticipating the questioning, nearly four decades later, of AS. Altekar’s idealistic perception of women’s status in ancient India which had become influential during the phase of nationalist struggle and continues to remain so, notwithstanding a plethora of research sponsored and inspired by the numerous feminist scholars, organizations and movements. He continued to express his interest in women’s history from time to time, but, in course of his professional career spanning over six decades, he focused his attention mainly on issues like caste and its inherent inequities, state formation and role of technology and its linkage with early Indian social formations, social context of ideology and so on, and produced avant gardist works on various aspects of Indian history. II

British and Indian scholars before him had written about Indian social structure, especially the caste system, the former denouncing the Indian society and the latter shying away from any discussion of its seamy side and adopting, by and large, a reformist approach. Some scholars influenced by Marxian ideas (e.g., AN. Bose 1942-4; B.N. Dutt 1944; G.F. Ilyin 1952, S.A. Dange 1949, D.O. Kosambi 1946) also studied ancient Indian social structure and debunked many ‘sedulously cherished myths of nationalist historiography’ but did not pay attention to the travails of the lower orders which attracted the attention of B.R. Ambedkar (1946, 1948). However, his flawed handling of the sources resulted in fallacious theories of the origin of sudras and untouchables. In a sense therefore R.S. Sharma was the first professional historian to make an in-depth analysis of sources stretching over a long period to trace the history of caste and delineate the vicissitudes of the lower social orders. His path breaking work 5udras in Ancient India, a doctoral dissertation completed at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, in 1956, was first published in 1958 and has had several editions ever since. Based on a rigorous scrutiny of a wide range of ancient Indian literary texts representing the brahmanical world-view, it examined the position of the sudras and untouchables up to the end of the Gupta period, captured the voices of the oppressed masses in them and anticipated the later subaltern historiography, though, of course, without sharing the anti-Marxism of its enthusiastic exponents. The main assumption of Sharma, unlike that of the British and other Western social scientists, notably Louis Dumont, was that the Indian social structure was far from being static and was ever changing. He asserted that the position of the lower orders, inextricably linked with their changing relations with the means of production, underwent changes over time. This view, however, may not be acceptable to scholars, who, being averse to materialist explanation of historical phenomena, assign centrality to ritual hierarchy or to ritual purity/ pollution in the formation and functioning of caste. Sharma’s views on slavery, like those on the sudras and other lower sections, also may not be acceptable to many. The number of slaves in the Vedic period, he rightly suggests, was not large and, they worked mostly as domestic servants, having nothing to do with productive activities. When their number grew in the age of the Buddha, and in the Maurya period, slavery, according to him, ‘played a very considerable role in agricultural production’ (emphasis added) but Sharma hesitates in describing the Mauryan society as ‘slave society’ and calls it a ‘slave-owning society instead. Similarly, Sharma adduces evidence to show that in post-Maurya and Gupta times the social fabric was supported mainly by the tax paying vaisyas and the toiling sudras and describes it as ‘vaisya-sudra society’ or ‘vaisya-sudra social formation’. These descriptive categories certainly indicate the changing nature of the early Indian social structure. But, being at variance with Marx’s nomenclature of modes of production, they may also imply the incomparability of Indian caste system with non-Indian societies and may be at odds with the universalism inherent in his Marxist method.

R.S. Sharma retained his interest in the study of ancient Indian social structure and its material basis throughout his professional career and, through his highly original and insightful writings, deepened our understanding of social changes in the early medieval period which, he was the first to show, witnessed the proliferation of castes including the untouchable ones. But, puzzling though it may seem, he did not explain why the phenomena of caste and untouchability developed only in India and not elsewhere.

| Preface | 9 | |

| Introduction: Engaging with R.S. Sharma and His Historiography | 11 | |

| 1 | Heritage, Archaeology and the Indus Civilization | 39 |

| 2 | Mitanni Indo-Aryan Mazda and the Date of the Rgveda | 73 |

| 3 | The Idea of the ‘South’ (Daksina) in Early India | 97 |

| 4 | Claudius Ptolemy and the Political Geography of Ancient India | 123 |

| 5 | Archaeology in Bihar: Trends and Prospects | 133 |

| 6 | Interpreting Historical Archaeology of Coastal Bengal: Possibilities and Limitations | 155 |

| 7 | Gold in Ancient Indian Material and Religious Culture | 181 |

| 8 | Urbanization at Early Historic Vaisali, c. 600 BCE-400 CE | 213 |

| 9 | Pali Literature and Urbanism | 243 |

| 10 | The Ethics of Consumption: Food Preferences and Dietary Practices in the Jatakas | 281 |

| 11 | Misunderstood Origins: How Buddhism Fooled Modern Scholarship and Itself | 307 |

| 12 | History and Literature: Unravelling Conversations in the Local Context of Buddhist Deccan | 327 |

| 13 | Trade Networks in North-West India and Bactria: The Material Record of Indo-Greek Contact | 347 |

| 14 | From the Oxus to the Indus: Religion and Politics of the Bactrian and Indo-Greek Rulers | 373 |

| 15 | The Influence of the Arthasastra on the Kamasutra | 391 |

| 16 | Women at Work and their Enemies: A Reappraisal of the Kamasutra V, 5. 5-10 | 413 |

| 17 | The Socio-Sexual World of the vesavasa and Antahpura: A Study in Contrast | 429 |

| 18 | Re-Constructing the Social Histories of the Puranas: Kings and Wives as Upholder of Propriety in the Matsyamahapurana | 447 |

| 19 | Alternatives Marginalized: Fluctuations in Brahmanical Paradigms on the Niyoga | 475 |

| 20 | Caste, Gender and Ideology in the Making of Traditional India | 513 |

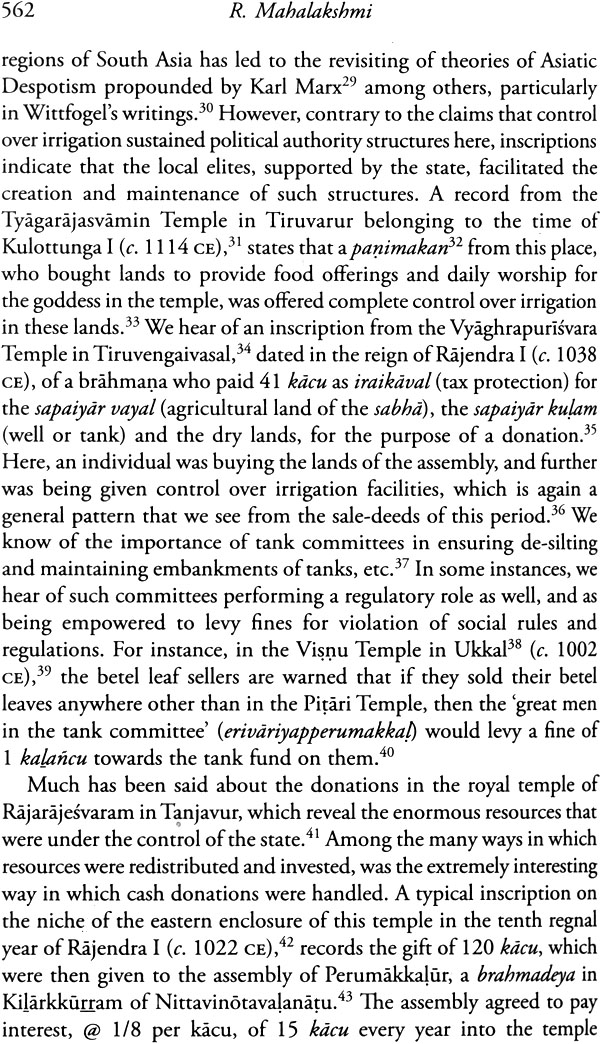

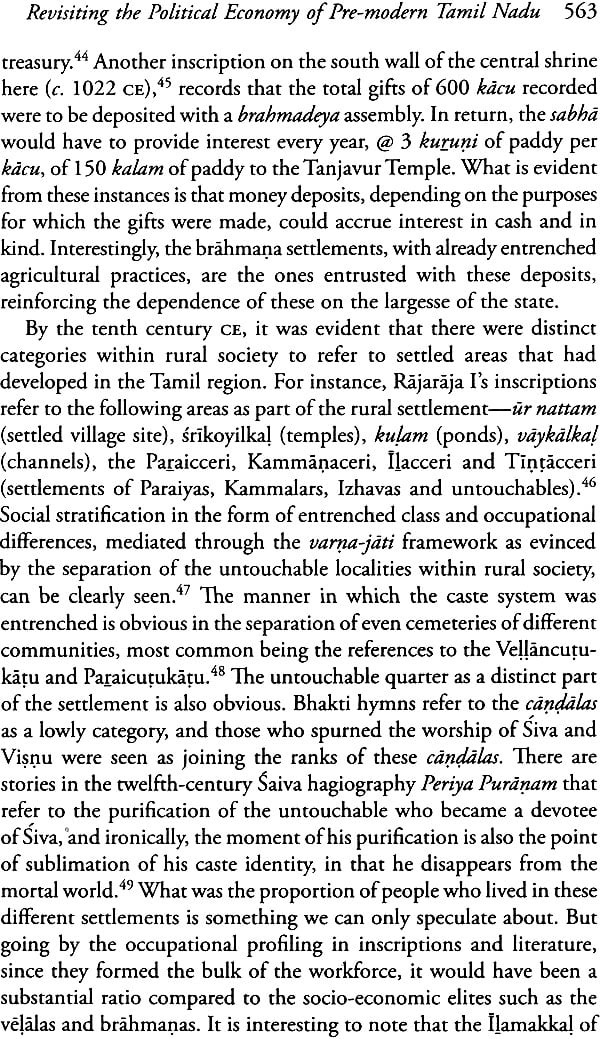

| 21 | Revisiting the Political Economy of Pre-modern Tamil Nadu | 555 |

| 22 | Monetary History of Bengal: ‘Issues and Non-Issues’ | 585 |

| 23 | A Tenth-century Brahmapura in Srihatta and Related Issues | 607 |

| 24 | Hunting for Food: Non-vegetarian India | 627 |

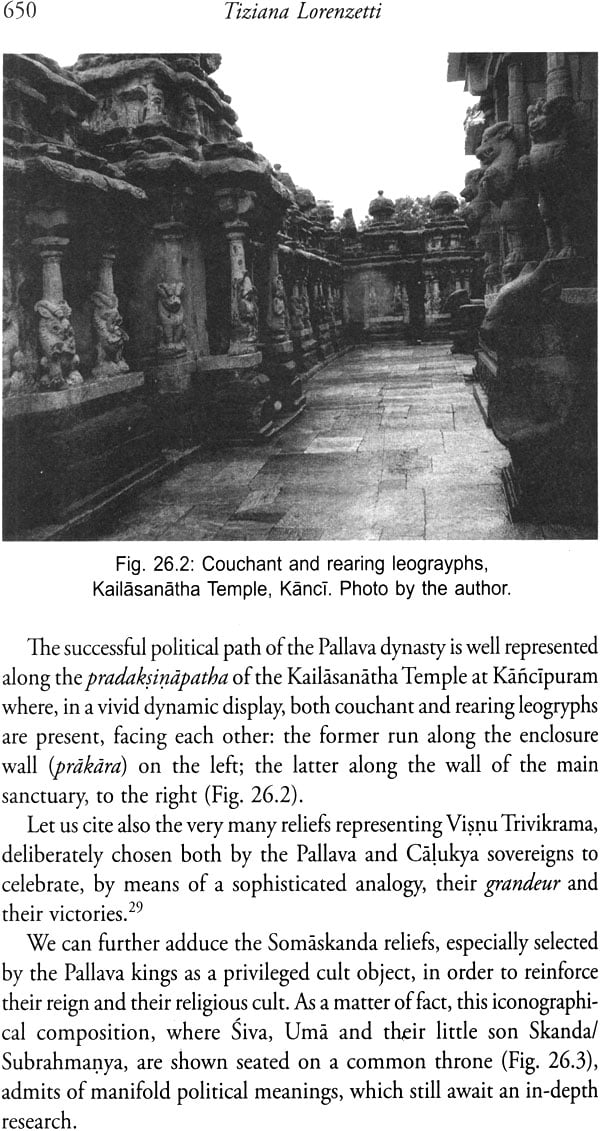

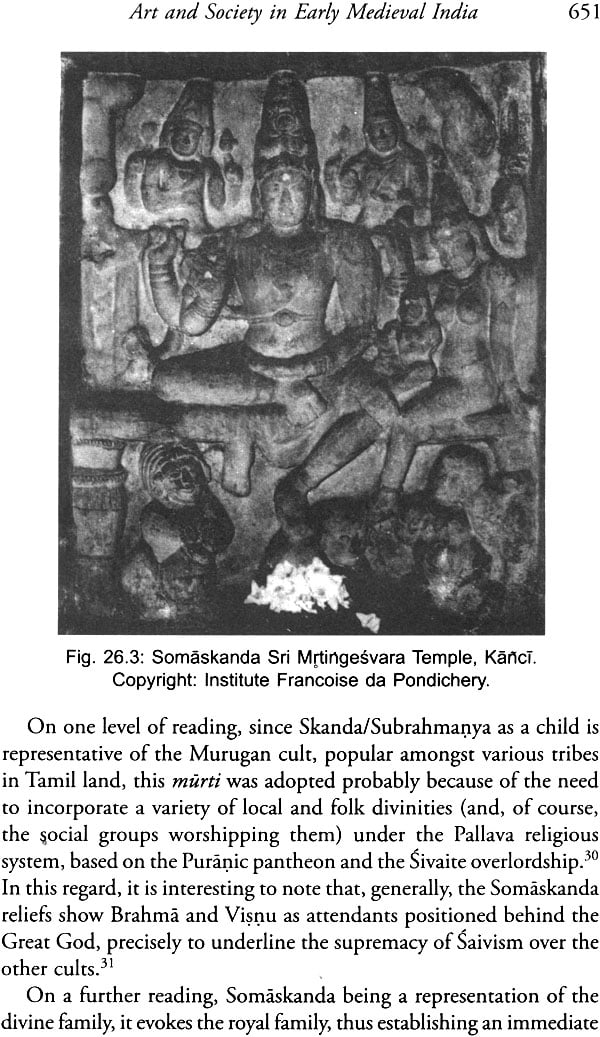

| 25 | Art and Society in Early Medieval India | 645 |

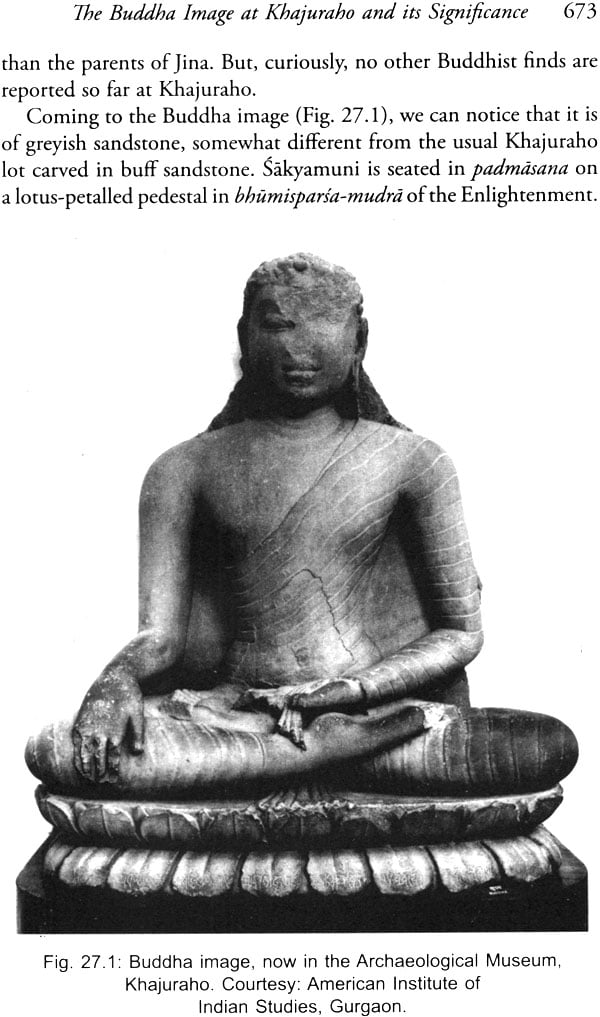

| 26 | The Buddha Image at Khajuraho and its Significance | 671 |

| 27 | Remembering Prof. R.S. Sharma | 683 |

| 28 | Professor R.S. Sharma: Some Early Memories | 689 |

| 29 | ‘Shudra Sharma: A Personal Tribute to Ram Sharan Sharma | 697 |

| 30 | Secular Historian | 699 |

| 31 | A Tribute: The People’s Historian | 705 |

| List of Contributors | 711 |