Culture of Bengal Through the Ages- Some Aspects (An Old and Rare with pin hole Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAX512 |

| Author: | Bhaskar Chattopadhyay |

| Publisher: | The University of Burdwan |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1988 |

| Pages: | 444 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 770 gm |

Book Description

The history of the culture of Bengal may be traced from the pre- and proto-historic age. This is evident from the discovery of Paleolithic, microlithic, Neolithic and chalcolithic tools and implements in different parts of the country. While the Paleolithic men in Bengal, as in other parts of India, were at the stage of savagery, collecting food from jungles and leading a community life, the Neolithic men learnt the art of producing food, manufacturing potteries, igniting fire and cooking their meals and thus reached the stage of barbarism.

"Indian type of feudalism" that had its beginning in early medieval Bengal was consolidated under the Sultans of Bengal. Rural economy based on agriculture was the foundation upon which was set up the super-structure of Bengali culture. Agriculture, along with small industries, constituted the self-sufficiency of the village-economy. The extent of landholding determined the social status of the people. The position of poor peasants, the degraded sudras, was reduced to that of serfs. The Serfs and the women-folk were deprived of social and religious rights and privileges. Sri Chaitanya was the first man who started a movement with an objective to establish an equality of rights and privileges. "The Renaissance which we owe to English rule in the nineteenth century had a precursor- a faint glimmer of dawn no doubt two hundred and fifty years earlier" and that is `Chaitanya Renaissance'.

The 'Nineteenth Century Renaissance' in Bengal was infact, the creation of the English-educated middle class people. The cultural development centered in and around Calcutta and had the remotest link with the villages inhabited by the eighty percent of the population of Bengal. The renaissance, of course, reflected the intellectual attainment but failed to bring about any change in the society and economy. European mercantilism touched on the fringes of the society. The predominance of the village-based agrarian economy remained undisturbed. Neither the peasants and artisans in the villages, nor the labourers and small traders living in Calcutta itself, could participate in the cultural progress of nineteenth century Bengal. The regeneration in society and culture did not grow from the roots in the soil. The type of education that the English rulers had introduced in Bengal was for the privileged few. The vast mass of illiterate people wallowed in complete ignorance. In this background, socio-religious reforms or social legislations, engineered by the upper class in collaboration with the government, could hardly be appreciated by the majority of the people. The emancipation of women and Sudras, that was promised by the reformation movement of Chaitanya, was echoed in the speeches and writings of the nineteenth century Bengali intellectuals. Vivekananda's programme of upliftment of the poor and downtrodden and Rabindranath's experiments in rural reconstruction remain yet to be fulfilled. Tagore's efforts for the revival of rural economy by the application of modern science and technology and also for the regeneration of rural culture comprising folk art, dance, music and literature, with somewhat urban sophistication and refinement, indicate the trends in the twentyieth century Bengali culture.

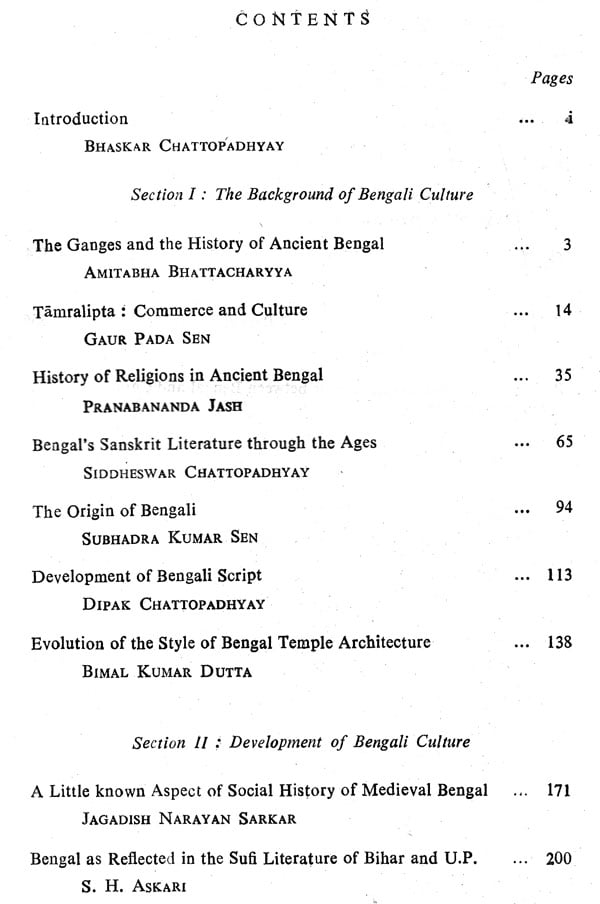

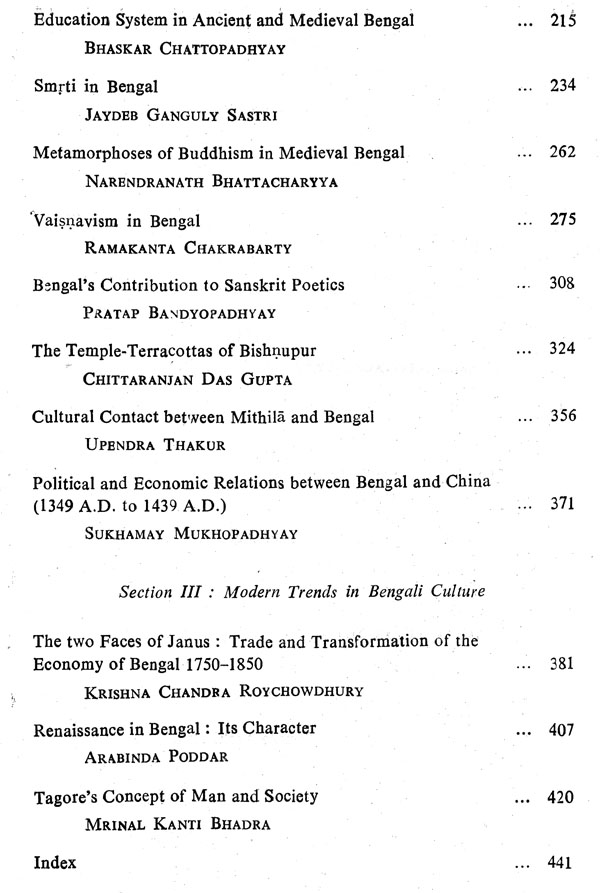

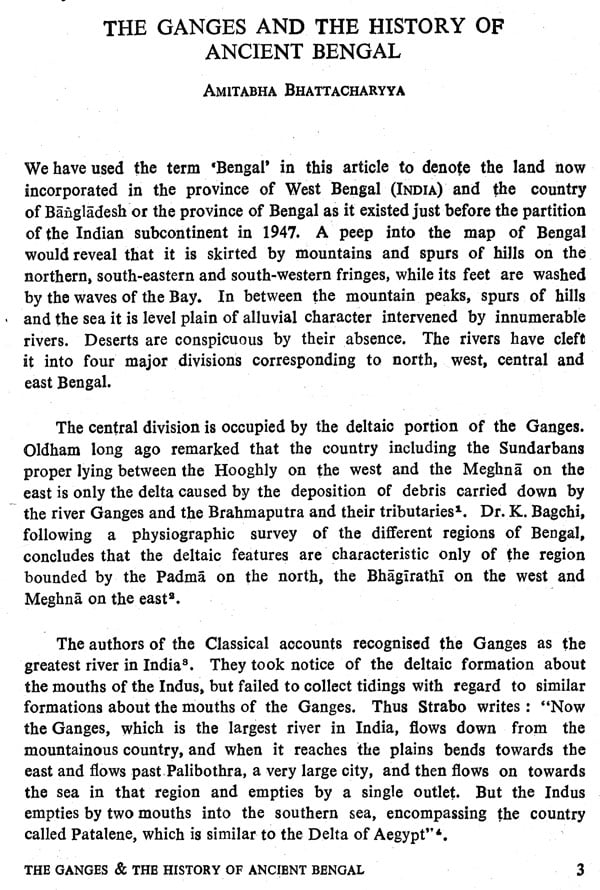

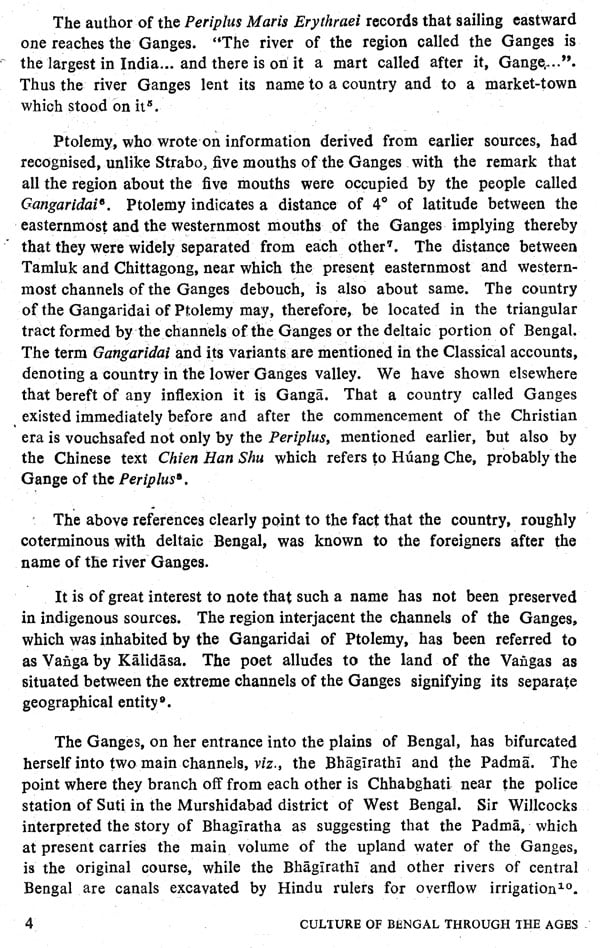

Book's Contents and Sample Pages