The Eye of The Serpent

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAI491 |

| Author: | S Theodore Baskaran |

| Publisher: | Tranquebar Press |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2013 |

| ISBN: | 9789383260744 |

| Pages: | 308 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8 inch X 5 inch |

| Weight | 250 gm |

Book Description

In almost ten decades of its evolution, Tamil cinema has grown to exert a dominant influence on the social and political life of Tamil Nadu in a manner that is unparalleled elsewhere in the world. This seminal volume is an analytical study of Tamil cinema both as an art form and as a socio-political force. Theodore Baskaran traces its history, and presents the achievements of many filmmakers with colourful insights. For the film buff as well as the serious student of film studies, The Eye of the Serpent is a handy reference book on several aspects of Tamil cinema –its character and evolution , the songs and songwriters, filmmakers and script writers, the beginnings of the unique nexus between cinema and politics in Tamil Nadu and much more.

THE IMMENSE POPULARITY OF FILM AS AN ENTERTAINMENT form and its emergence in Tamil Nadu as a major cultural preoccupation underscores the significance of the role of audiovisual communication in Tamil society. Over the years, films ––have become essential instruments for the conduct of any mass campaign that calls for manipulation of its target population. The quantum growth in television and video-viewing has further enhanced the influence of cinema as these media serve as virtual extensions of filmic exhibition. Obviously, such an important development in the cultural and communication environment-which has been under way for over twenty-five years now-merits examination and understanding.

Within three decades of its advent, Tamil cinema penetrated rural areas, piggybacking on the rural electrification programme, and began catering to predominantly illiterate masses. With its ability to reach vast audiences, its breadth of appeal widened. This appeal further increased, when the indigenous classical and folk traditions-sometimes called the "Great" and "Little" traditions respectively-were brought together and amalgamated in Tamil films. Today, Tamil films enjoy a very high exposure rate. There are 2,548 cinema houses, of which 213 are semi-permanent and 892 are "touring" cinemas. The last category operates in interior rural areas: Bulk of the films screened in Tamil Nadu are made in the state capital, Chennai.

Over the ninety-six years of its existence, Tamil cinema has become one of the most domineering influences in the cultural and political life of Tamil Nadu. As filmmakers treated the subject of human beings in different situations, their films inevitably touched upon social and political issues.

Various movements in Tamil Nadu, in turn, shaped the development of Tamil cinema. Even as it gave expression to the social comments and opinions of filmmakers, Tamil cinema also reflected the changing social concerns and moods of the period.

Popular films of any given period must try to satisfy the current desires and tastes of the masses to succeed; and the film industry, which is as vitally interested in profits as any commercial venture, adjusts itself as much as is possible and practicable, to the changes in the socio-political climate of society. Thus, cinema by its very nature mirrors the diverse strands of social thought and events during the various phases of a country's history. Many examples from the history of world cinema can be cited in support of this point of view; for instance the Great Depression and the Hollywood films of the 1930s. If Tamil cinema is studied as a socio- political force, then its dual role as a propagator of ideas and as a document of social mores will become evident.

Cinema is the only art form in Tamil Nadu, whose origin can be traced with some certainty. And this is the only secular art form, as distinct from traditional art forms which invariably have their basis in some modes of religious practice. Evolving in the context of a long and vigorous aural tradition, Tamil cinema developed some very interesting characteristics. The diverse currents and crosscurrents of thought that went into various social and political movements in Tamil Nadu can be traced through a study of Tamil cinema.

Therefore, it was this connection between Tamil cinema and these movements that gave rise to the phenomenon of the star-politician and the use of films for explicit political propaganda.

Yet, there have been very few studies on Tamil cinema. In attempting to understand the performing arts of Tamil Nadu, such as Carnatic music or Bharatanatyam, including their social dimensions, there are numerous works one can turn to. In the field of Tamil literature too, there are many books which serve to provide an introduction. But when it comes to cinema, which has had a much greater impact on Tamil society, there is very little material. This apathy towards the study of cinema has been discernible right from the early years, and has been one of the factors that shaped the character of Tamil cinema. Film criticism and film studies did not develop and even after nine decades of its existence, this apathy still continues. The intelligentsia, which refused to take any notice of this new medium when it first appeared on the social scene, now fulminates against it for being escapist and shallow, long after its metamorphosis as a formidable force has come to pass.

While this indifference to the serious study of cinema is common to many other countries, in India it was further compounded by the rigidity of social stratification. In Tamil Nadu, where caste barriers are strictly defined, with exclusive entertainment forms for different classes, the appearance of an entertainment form that cut across all sections of society was, in the first instance, a development that the elite were not prepared to reconcile with. Early Tamil cinema, with its commercial orientation and sensational content, quickly endeared itself to the heterogenous mass audience and, by the same process, alienated the elite. How could an entertainment form, so avidly patronized by the plebeian masses attract the elite also to its fold? A position had to be taken by them vis-a-vis cinema and they took a rigidly negative one. This negative stance, in the course of its expression had many ramifications and continues to do so even now.

In recent years, however, one notices a shift away from this stance. Since I wrote The Message Bearers more than thirty years ago, scholastic interest in Tamil cinema has grown considerably. Elsewhere in the world, the relevance of cinema to historiography is being recognized. The conference on 'Film and Historian' organized by the University College in London in 1968 marked the recognition of cinema as an area of study. Film studies as a discipline, is in the process of acquiring an academic tradition as scholars are gradually awakening to this exciting possibility. Many academics, in India and abroad, choose cinema-related topics for their study of Tamil Nadu. Yet, we have very few works that can serve as an introduction to this interesting area of study. And, there is no baseline data available. If one intends to understand anything of Tamil cinema, it is not enough merely to watch films or write about their aesthetics. We need to study cinema. It is this need which justifies efforts such as this book.

In choosing the fifty films which are treated in this book, I have tried to make a representative selection. The films I have chosen are not all classics nor were they all successful films. They are instead illustrative of specific genres of films which are important for one reason or another. The availability of a film for viewing was also a determining factor. Obviously, this may have resulted in some significant omissions which the reader might readily notice. I would liked to have included She Was Born to Live/Vazhapirandhaval (1953); but I could not locate a print. The list of filmmakers was also subject to a similar constraint. It was difficult to obtain authentic information on the works of many filmmakers. The questionnaire I sent out to many contemporary filmmakers evoked very little response. And on some, like R Padmanabhan, I could gather only the barest details.

| Acknowledgements | ix | |

| Introduction | xi | |

| Chapter One | The Early Days-Silent Movies | 1 |

| Chapter Two | And Then Came the Voices | 12 |

| Chapter Three | Era of the Dialogue writer and the Cinema of Dissent | 29 |

| Chapter Four | Songs in Tamil Cinema | 39 |

| Chapter Five | Dialogue in Tamil Films | 62 |

| Chapter Six | Satyamurthi-the Link that Snapped | 71 |

| Chapter Seven | The Films | 90 |

| Chapter Eight | The Filmmakers | 179 |

| Chapter Nine | The Songswriters | 221 |

| Milestones of Tamil Cinema | 235 | |

| Bibliography | 241 | |

| Articles | 245 | |

| Glossary | 247 | |

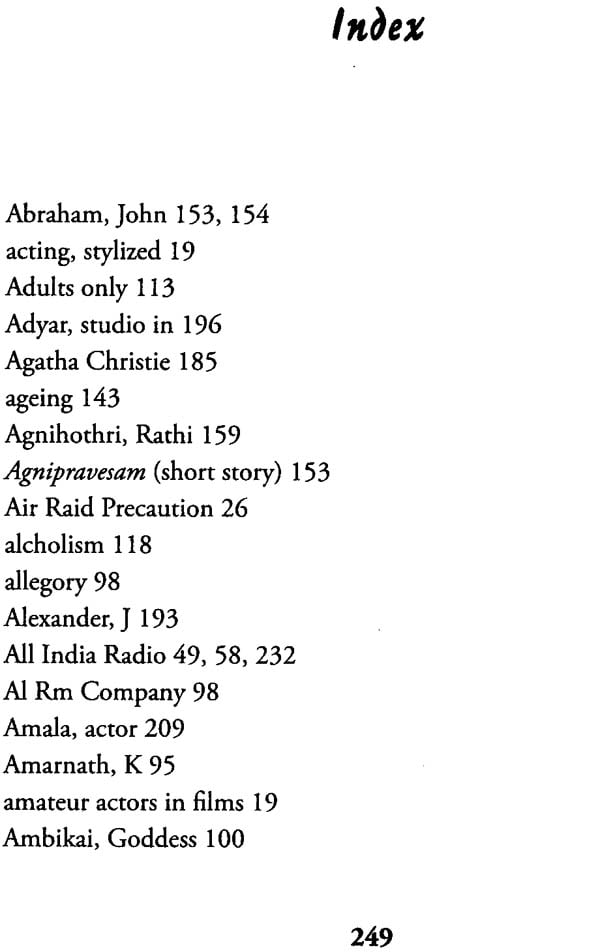

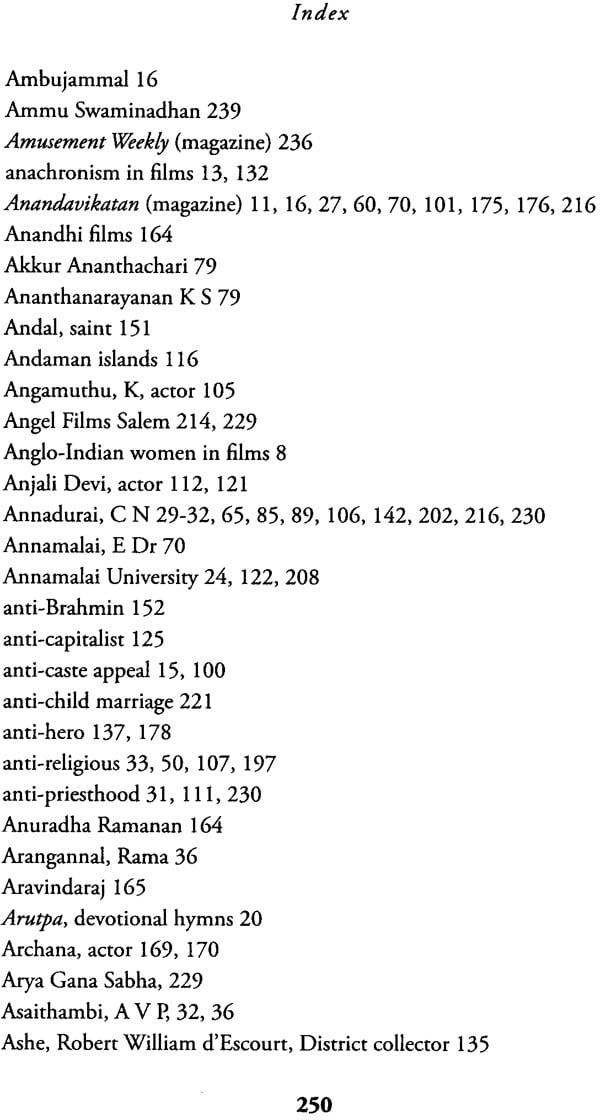

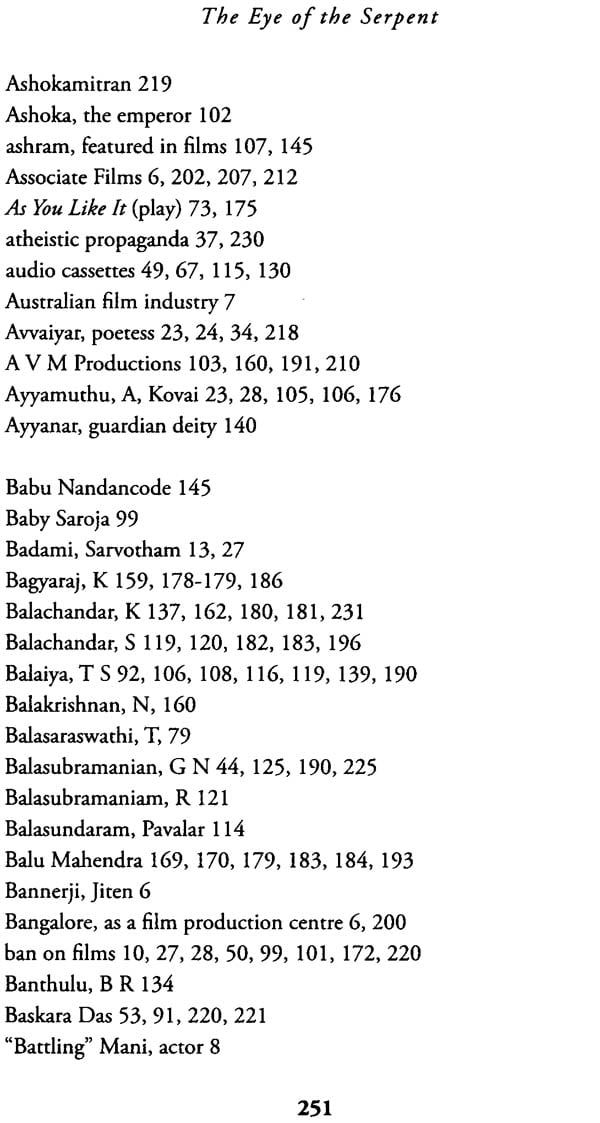

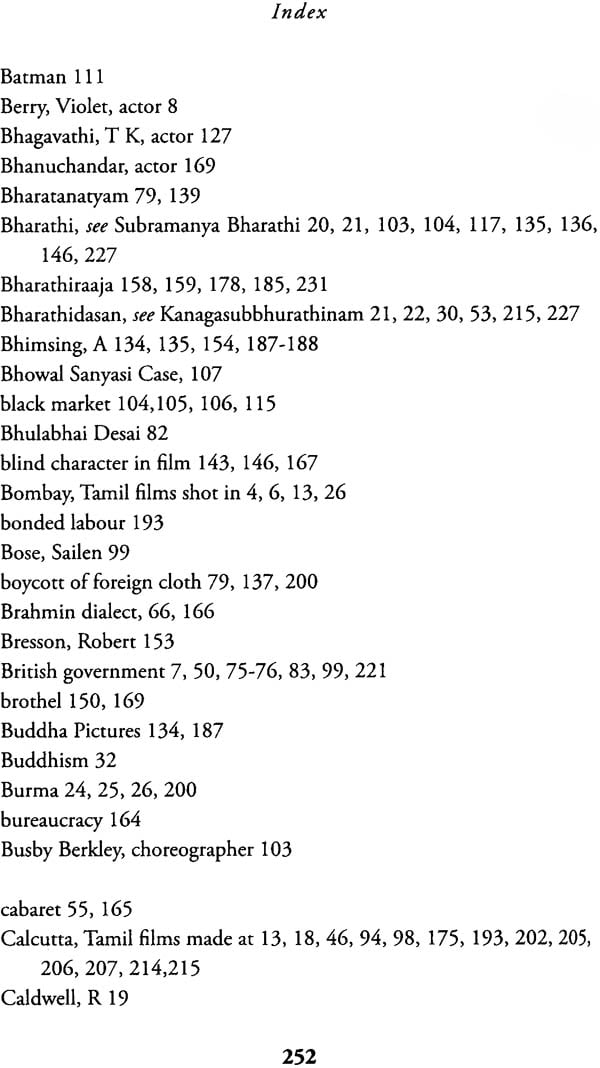

| Index | 249 | |

| Index to Film Titles | 278 |