Kena Upanisad

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAH437 |

| Author: | Swami Muni Narayana Prasad |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | Sanskrit text with Transliteration and English Translation |

| Edition: | 2011 |

| ISBN: | 9788124605837 |

| Pages: | 144 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 220 gm |

Book Description

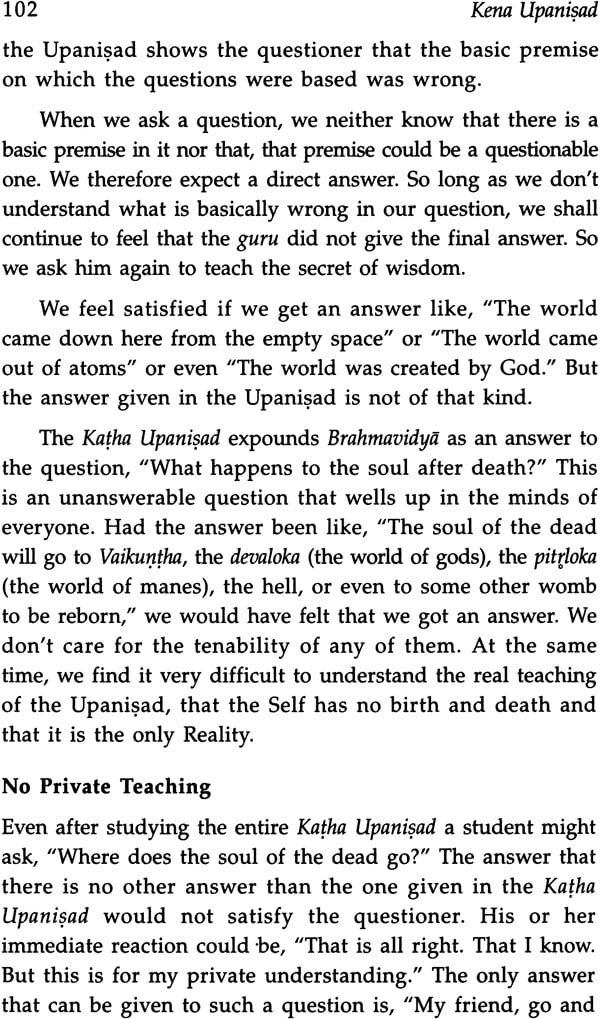

Kenopanisad is one if the major Upanisads containing the quintessence of the teaching of the ancient Indian seers. It represents their spiritual quest to apprehend the nature of the Ultimate Being and comprises the yearning for the wisdom that explains the relation of human life to the world and the reality. The beauty of this Upanisad is greatly enhanced by the dialogue between the disciple and the preceptor, through which it continues its quest.

Swami Muni Narayana Prasad, the renowned scholar on the Upanisadic tradition, renders a superbly novel analysis of this difficult text in the light of the modern man's need for value and spiritual security making a strikingly beautiful synthesis between the ancient and the modern. Presenting the teaching of Kenopanisad in the backdrop of the recent developments in the area of physics, chemistry, biology and psychology is no mean task and constitutes the exclusiveness of this book. The disciplines of science in the pursuit of the basic truth stumble at some invisible and unconceptualisable Reality, which may be another name for mysticism. Through very cogent arguments the another has successfully vindicated that mysticism is a corollary to scientific investigation and not opposed to it.

The author's prolonged association with the Upanisadic thought along with the insight he received from the works of his preceptors, Narayana Guru and Nataraja Guru, makes the commentaries of this text stimulating and unique. The original Sanskrit text along with the Roman transliteration and English paraphrasing enhance the value of this monumental commentary.

Swami Muni Narayana Prasad is presently the Head of the Narayana Gurukula, a Guru-Disciple foundation founded by Nataraja Guru, the disciple-successor of Narayana Guru. He has spent three years in Fiji teaching Indian philosophy and has travelled round the world giving classes. Become a disciple of Nataraja Guru in 1960 and was initiated as a renunciate in 1984. His published works in English include, Karma and Reincarnation – The Vedantic Perspective; Basic Lesson on India's Wisdom; Vedanta Sutras of Narayana Guru; Commentaries on the Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Taittiriya and Aitareya Upanisads.

The most interesting item of the daily routine of life in the Gurukula, ever since I became an inmate of it, had been the early morning recitation of the selected portions of the Upanisads. Eventually I began to explain the meaning of them to the kids in a simple way. Finally when I decided to lead the life of a renunciate, the special direction given by my Guru, Nataraja Guru, was that my sannyasa-life should be centred round the Upanisads and their tradition.

My main interest has always been on the philosophy of Narayana Guru who had attained final samadhi before I was born. My acquaintance with him was only through his highly philosophical poems as interpreted by Nataraja Guru based on the dialectical way of approach, which had been known to the ancient rsis of India as yoga-buddhi, as is evident from the Bhagavad-Gita. Swami Aryabhatan, one of the well-known orators in the Malayalam language on spiritual matters, once told me that Narayana Guru once asked him to give lectures expounding the Upanisads in his own way. The Guru gave this direction when he met Swami Aryabhatan in his younger days as a talented orator. This gave me the courage to interpret the Upanisads in my own way. Narayana Guru's philosophy gave me an insight into many of the puzzling passages in the Upanisads.

I took up the Katha Upanisad for giving a free interpretation, and my intention was not of writing a publishable book. My aspiration was to delve deep into the philosophy of the Upanisad as I was convinced that there was no other way of doing it. It was well received by readers on serializing in the Malayalam philosophical monthly, The Gurukulam. Then Guru Nitya Chaitanya Yati and self together resolved to write commentaries on all the ten major Upanisads, the Brhadara1Jyaka and Chandogya to be done by him and the rest by me. But he had already written his commentary on the Isa and Mandukya Upanisads by then. I therefore actually had to do only the remaining six. That is how this series originated.

I wrote the commentaries originally in Malayalam, my mother tongue. My interpretation of the Katha Upanisad was translated to English and was serialised in the Gurukulam Quarterly published from the United States. When I found that it was well received, I dared to make the English version of the others too.

Excepting the Katha Upanisad and the Mundaka Upanisad all were originally written as a result of the collective thinking of a group of research scholars who were residing with me at the Gurukula. I am indebted to all of them. I made the English version of the Kena Upanisad, while I was living in Fiji, a small island country in South Pacific, where I had enough spare time to concentrate on such works.

The trustees of the Gita Ashram in Fiji were also much helpful. Dr Peter Oppenheimer of the USA took all the trouble to go through the entire text carefully and to edit it. I am grateful to all of them. I am also thankful to M/s D.K. Printworld for including my commentaries in their series "Rediscovering Indian Literary Classics."

With prostrations at the feet of both Narayana Guru and Nataraja Guru as well as the unknown rsis of yore, I offer this commentary on the Kena Upanisad as a forerunner to a new tradition of freely interpreting the scriptures of India, while adhering strictly to the essence of their comprehensive yet unitive philosophical vision.

Every Upanisad is appended to a Veda forming the last part of it. So the Upanisads used to be called Vedantas, meaning the end of the Vedas. The Kena Upanisad is a part of Talavakara Brahmana which comes under the Sama Veda. It is called so because it begins with the word kena. Moreover, the main problem raised and answered in this Upanisad is also indicated by the word kena which means, "by whom?" The question raised in this Upanisad is "By whom are all the faculties in us willed and directed?"

In another sense also the Upanisads could be called Vedanta. Veda means knowledge and anta, end or conclusion. Thus Vedanta means the final conclusion of knowledge. This does not mean that it enables one to know everything knowable. Such a knowledge is impossible, and does not give us the satisfaction we seek. But there is yet another awareness, attaining which all the desires to know further ceases. That awareness makes evident to us the meaninglessness of all the knowledge that we were trying to accumulate. That awareness of self-fulfilment is the end of our search for knowledge. In that sense it could be called Vedanta. That awareness is the theme of all the Upanisads, and is an experience of the non-difference of our personal existence from the totality of existence. Thus we realise the ultimate meaning of our life which is one with the life of the whole. This realisation makes our life a continuity of the flow of contentment, the ultimate aim of all philosophies and also of the Upanisads.

The Sanskrit word for philosophy is darsana. Darsana means a vision. It is a vision of the oneness of the ends and means of life, where there is no room for the differentiation of the knower, the object of knowledge and the act of knowing. Each Upanisad leads us to this vision using a specific question as an instrument. The Kena Upanisad raises the question, "What is that principle which urges our mind, vitality, word and senses, to function?"

Being faithful to the traditional convention of starting a serious study with a prayerful attitude, this Upanisad also begins with an invocation for peace, which is called santi patha:

aum apyayantu mamangani vak pranas caksuh srotram atho

balam indriyani ca sarvani I sarvam brahmaupanisadam ma 'ham

brahma nirakuryam ma ma brahma nirakarod anirakaranama

astu anirakaranama me 'stu I tad atmani nirate ya upanisatsu

dharmas te mayi santu te mayi santu II

aum santih santih santih II

May my limbs, speech, vital breath, eyes, ears, as also my strength and all the senses grow vigorous. All this is the Absolute (Brahman) referred to in the Upanisads, May I never negate the Absolute. May the Absolute never negate me. May there be no negating. May there be non-negating in me. Let those basic tenets enunciated in the Upanisads, rest in the Self. Let them be in me. Aum Peace! Peace! Peace!

One yearns to know the meaning of life when it is felt that one's own existence is losing its meaning. When one's existence is fully stabilised in oneself it is called svasthata in Sanskrit, which in common usage means, a healthy condition. The feeling of instability is called asvasthata. This state could be caused by an unexpected unfavourable reaction from a beloved person. Taking away from us what has been considered the most valuable or dearest may also cause the same state. A sudden attack from other beings, including germs, rendering one helpless, may also happen to be the reason. All these are sufferings caused by other beings. Such sufferings effected by other beings are called adhibhautika dukhas in Sanskrit.

Our expectations in life are many. We always toil to fulfil them. Sometimes something untoward happens, which makes all our efforts and expectations meaningless. But had one been able to do whatever is normal with a responsible person, without any expectation about its result, this unexpected turning of events would not have caused misery. Such sufferings are thus caused by our own expectations. These self-caused sufferings are called adhyatmika duhkhas. These can happen in different fields and levels of our life, ranging from the troubles one makes for oneself because of one's foolish fancifulness, to the internal agony one feels when one has a genuine thirst for wisdom, but finds no way to quench it.

Sometimes unexpected tragedies happen to us by the decision of Providence, as it were. At that moment we may feel as if we were thrown into the abyss of a black hole. Sometimes an entire family disappears from our midst, when met with a tragic accident. By chance an infant child of the family could be seen lying safely at a distance, innocent of all the vicissitudes of life. At that moment even the smile of the child would be taken by us as part of a pathetic scene. Such sufferings, caused not by the fault of anyone, are termed adhidaivika dukhas.

| Preface | v |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Section One | 7 |

| Section Two | 37 |

| Section Three | 65 |

| Section Four | 87 |

| Glossary | 111 |

| Bibliography | 121 |

| Index | 125 |