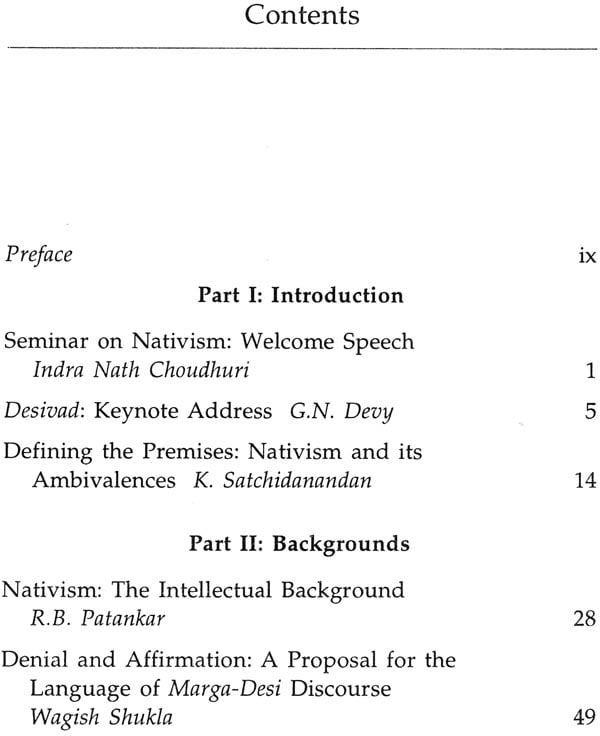

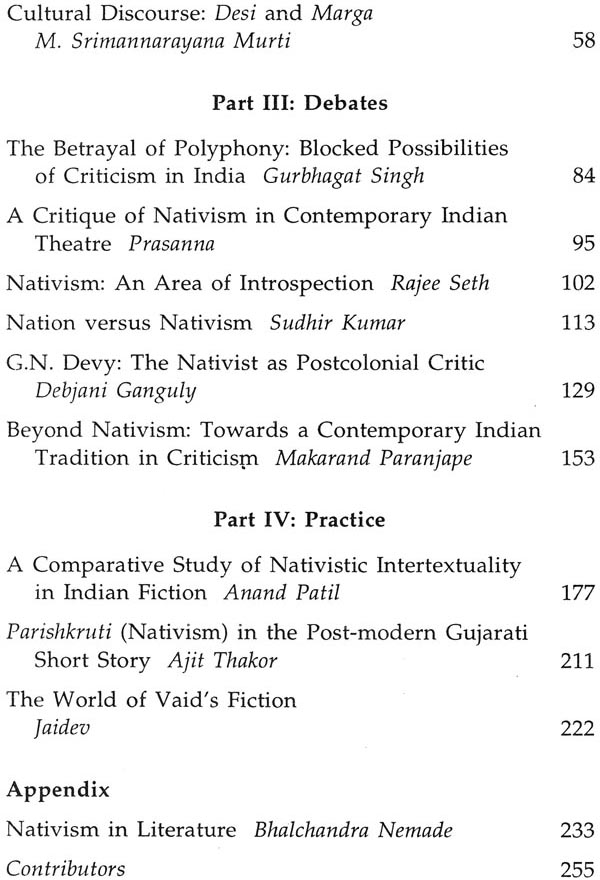

Nativism: Essays in Criticism

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAR299 |

| Author: | Makarand Paranjape |

| Publisher: | SAHITYA AKADEMI, DELHI |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2017 |

| ISBN: | 9788126001682 |

| Pages: | 270 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 360 gm |

Book Description

Emanating from the Bahujan Samaj – the majority of ordinary people who make up the plurality of Indian civilization – Nativism is a form of indigenous literary criticism whose agenda can be summed up as a cry for cultural self-respect and autonomy. In the welter of derived and derivative critical theories which confound contemporary Indian cultural studies, nativism is, perhaps, the only home-grown school of criticism to have emerged in post-Independence India.

In recent years, it has received greater attention because of the efforts of two bilingual critics, Bhalchandra Nemade and G.N. Devy. Based on a seminar on ‘The Concept of Desivad (Nativism) in Indian Literature," this book is the first collection of critical essays on the concept and its applications.

The fifteen essays included here introduce and define the concept, analyse its classical, medieval, and colonial back-grounds, trace its evolution into the contemporary critical field, debate its strengths and weaknesses and finally, attempt to put it into practice by applying it to cotemporary literary works. In addition, Bhalchandra Nemade’s original Marathi essay on nativism, published in 1983, which introduced the concept, is included here in its first, complete English translation.

All told, this book is a pioneering and timely intervention in the critical scene today. It poses a challenge to the dominant, market-driven, globalising, and totalising intellectual and cultural trends of our times which threaten to marginalize and subdue our native ways of life. What is more, it does so without uncritically yielding to imported technologies of subversion, whether Marxist, feminist, postmodernist, or otherwise. This book is an attempt to show that there are alternative possibilities of facing up to our present cultural crises.

Makarand Paranjape, Professor of English, Jawaharlal Nehru Univerisity, Delhi, is an English poet, novelist, and critic.

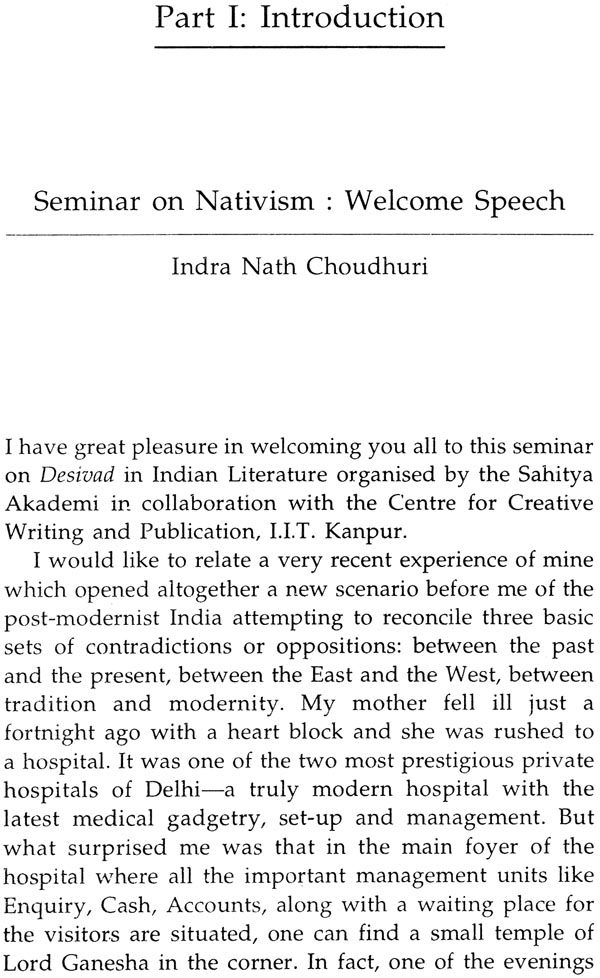

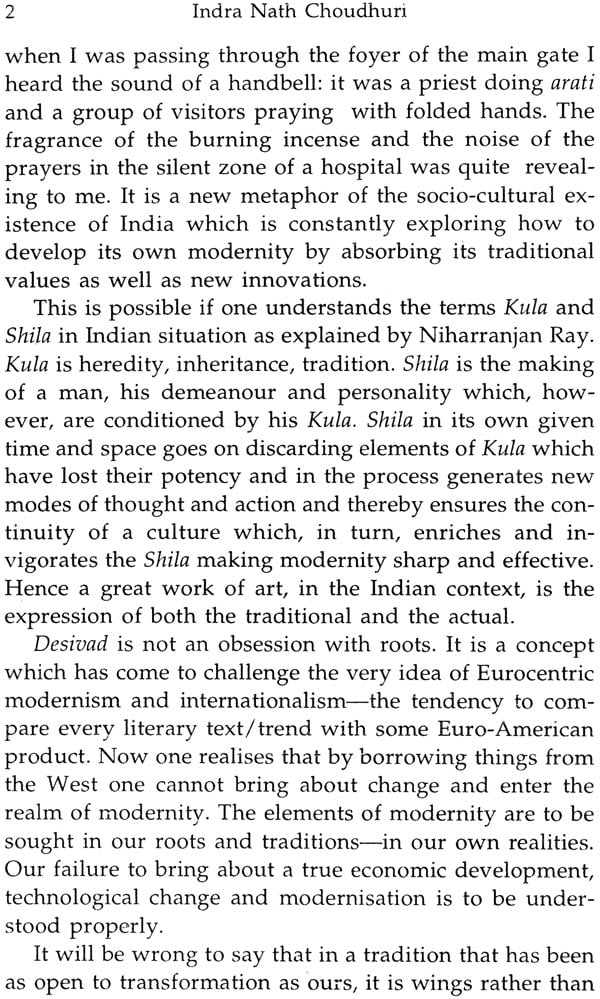

Most of these essays were originally written for and presented at the seminar on "Desivad in Indian Literature," sponsored by the Sahitya Akademi and the Centre for Creative Writing and Publication, Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, in January 1995. However, when I was asked to edit the proceedings of the seminar, I found that several alterations and additions would have to be made before a useful book on the subject could be com-piled. Some papers had to be left out and new ones commissioned. A few papers were revised before being sent for publication. Most of the useful and stimulating discussions that went on during the seminar, though they were recorded, had to be left out for reasons of space. I must mention that it was not possible to standardize the various and differing literary and research styles of these papers. That would have involved the kind and degree of labour which, even if desirable, would have delayed the book much beyond a permissible or reasonable interval after the holding of the seminar. Thus, on the whole, this book though it began with the "Desivad" seminar of 1995, actually differs from it considerably.

Among the major changes is the inclusion of two new papers--"Nation vs. Nativism" by Sudhir Kumar and "The Nativist as Post-colonial Critic" by Debjani Ganguly - and a book extract, "The World of Vaid's Fiction," from The Culture of Pastiche by Jaidev. I believe that these additions strengthen the volume by adding new dimensions to our understanding of nativism. Kumar's essay attempts to show that nativism is not necessarily and automatically opposed to nationalism as some contemporary critics of the nation imply. Ganguly's- lengthy discussion and evaluation of G. N. Devy's nativist criticism from a left-liberal point of view exposes the strengths and limitations of both nativism and her own cultural stance.

Jaidev's reading of Krishna Baldev Vaid's fiction is, in my opinion, a fine example of nativist criticism in practice. Jaidev shows precisely how Vaid succumbs to a sort of cultural inferiority complex, which leads him gradually to denigrate the native culture from which he springs. In addition to these three essays, I have included Bhal-chandra Nemade's original Marathi essay, "Sahityateel Deshiyata." First published in 1983, it not only gave Indian literary criticism the term nativism, but sparked off a lively debate. By translating and reprinting this essay, I believe that we are making available to a wider audience an important document of post-independence Indian criticism.

To many of us, both Bhalchandra Nemade and G. N. Devy are cultural heroes. They represent a very important and useful intervention in the evolving dynamics of Indian culture. Nemade, of course, is a leading Marathi novelist besides being a critic, poet, and Professor of Comparative Literature. Devy, also a Professor of English, is a translator, litretary historian, and bibliographer, be-sides being a lively and engaging critic. Both are provocative and opinionated, sometimes even given to extremes, but what is more important is that they are deeply rooted in our bhasha traditions and utterly dedicated to the cause of freeing Indian literary criticism from the shackles of Euro-American dominance. Both wish to make Indian criticism a more responsible, self-respecting, and Indo-centric activity. In that sense Nemade and Devy have brought the agenda of decolonization to Indian literary criticism.

What makes the anti-imperialism of these critics different from that of Western cultural critics or the latters' Indian followers, however, is their resistance to imported discourses of subversion and self-empowerment. Their work demonstrates not only the innate strength of native traditions and the capacity of such traditions to offer alternatives to received knowledge-systems, but also the awareness that a continuing dependence on Western modes of criticism and scholarship, even when apparently helpful in our struggle for selfhood, are ultimately self-defeating. Svaraj in ideas is possible only when we set our own agenda, when we stop succumbing to slavish and debilitating imitation of the latest intellecutal fads and fashions from the West, when we learn, in U. R. Anantha Murthy's famous phrase, to look in our own backyards" for our cultural resources.

Nemade and "Devy are different not only from Anglicised anti-imperialists, but also from Sanskritised ones. The hegemony of videshi ideas is not replaced by a counter-hegemony of Sanskirtic or Brahminical revivalism. Both critics are deeply aware of the oppressive nature of traditional Indian society, which had its own systems of suppressing the polyphony and polysemy of Indian society. Nativism, then, is a form of indigenism whose agenda can be summed up as a cry for cultural self-respect and autonomy emanating from the bahujan samaj--the majority of ordinary people who make up the plurality of Indian civilization.

What is more, nativism emphasizes the primacy of lan-guage in the production of culture. It favours and privileges the language and creativity of the masses over that of the elites, whether these are Anglicised or Sanskritised. In a sense, it represents the much under-rated and marginalized vernacularist position in the educational and cultural debates of early 19th century India. What most historians of culture emphasize is the victory of the Anglicists over the Orientalists (or Sanskritists); nativism reminds us that the more serious loss was the defeat of those who wanted education in the vernaculars or native languages of India. Vernaculars, etymologically, signify the languages of the slaves, thus of the common folk; this is what desi or bhasha means in the age-old marga-desi dialectic in Indian civilization, the language and culture of the common folk as opposed to that of the elites. Of course, language then assumes a wider significance as a cultural system which includes several of the defining and distinguishing traits of a com-munity or people. An interplay of the Great and Little traditions has always been a part of the Indian pluralism. If we add to this the more recent history of our struggle against colonialism and neo-colonialism, then we can more easily site nativism's aesthetic and political genealogy.

**Contents and Sample Pages**