Taru Kavya- Tree Poems

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAB394 |

| Author: | Various Authors |

| Publisher: | Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur |

| Language: | Sanskrit, Hindi and English |

| Edition: | 2016 |

| ISBN: | 9789381571811 |

| Pages: | 214 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 8.50 inches |

| Weight | 880 gm |

Book Description

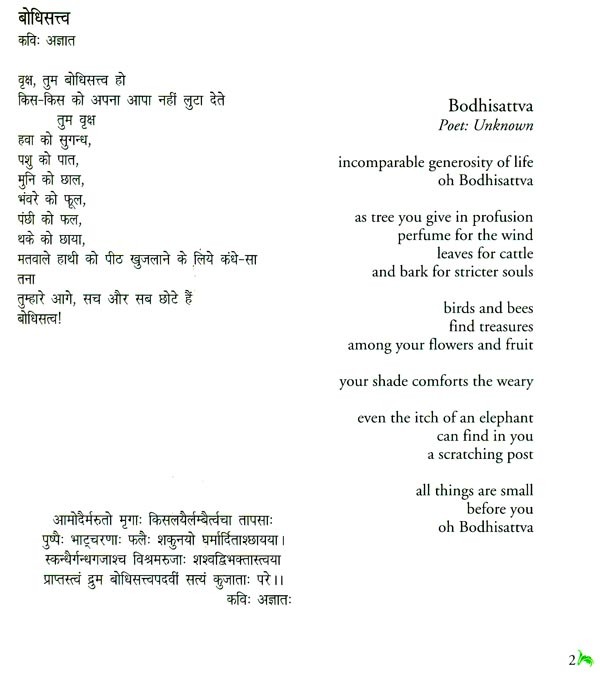

Taru Kavya (Tree Poems) is a reminder of the ecological roots of Indian Civilization - a civilization that Gurudev Tagore called Aranya sanskriti .

The poems ofTaru Kavya are the poetry from the soul of India . From the tree as Bodhisattva we learn unconditional love and unconditional giving. From the "Even dry leaves" we learn about the cycle of life, of the law of return, as leaves become humus and soil, protecting the Earth, recycling nutrition and water, recharging springs ,wells and streams .From Sardis’s poem we learn wisdom, from the diversity we learn democracy.

The forest also teaches us 'enoughness': as the principle of equity, enjoying the gifts of Nature without exploitation and accumulation. In The Religion of the Forest Tagore quotes from the ancient texts written in the forest: "Know all that moves in this moving world as enveloped by God; and find enjoyment through renunciation, not through greed of possession."

No species in a forest appropriates the share of another species. Every species sustains itself in cooperation with others.

This is Earth Democracy. These are the teachings from trees we receive through Taru Kavya.

In Tagore's writings, the forest was not just the source of knowledge and freedom: it was the source of beauty and joy, of art and aesthetics, of harmony and perfection. It symbolized the universe. In The Religion of the Forest, the poet says that our attitude of mind "guides our attempts to establish relations with the universe either by conquest or by union, either through the cultivation of power or through that of sympathy".

The forest teaches us union and compassion.

It is this 'unity in diversity' that is the basis of both ecological sustainability and democracy. Diversity without unity becomes the source of conflict and contest. Uniformity without diversity becomes the ground for external control. This is true of both Nature and culture. The forest is a unity in its diversity, and we are united with Nature through our relationship with the forest.

India has survived as a civilization because of the roots of its culture lie in Prakriti -in protection of the earth, the rivers, the forests, the trees.

Forests have always been central to Indian civilization. They have been worshipped as Aranyani, the Goddess of the Forest, the primary source of life and fertility, and the forest as a community has been viewed as a model for societal and civilization evolution. The diversity, harmony and self-sustaining nature of the forest formed the organizational principles guiding Indian civilization, the "aranya samskriti" (roughly translatable as "the culture of the forest" or "forest culture") was not a condition of primitiveness, but one of conscious choice. According to Rabindranath Tagore the distinctiveness of Indian culture consists of its having defined life in the forest as the highest form of cultural evolution. In his essay Tapovan, he writes:

Contemporary western civilization is built of brick and wood. It is rooted in the city. But Indian civilization has been distinctive in locating its source of regeneration, material and intellectual, in the forest, not the city. India's best ideas have come where man was in communion with trees and rivers and lakes, away from the crowds. The peace of the forest has helped the intellectual evolution of man. The culture of the forest has fuelled the culture of Indian society. The culture that has arisen from the forest has been influenced by the diverse processes of renewal of life which are always at play in the forest, varying from species to species, from season to season, in sight and sound and smell. The unifying principle of life in diversity, of democratic pluralism, thus became the principle of Indian civilization.

Not being caged in brick, wood and iron, Indian thinkers were surrounded by and linked to the life of the forest. The living forest was for them their shelter, their source of food. The intimate relationship between human life and living nature became the source of knowledge. Nature was not dead and inert in this knowledge system. The experience of life in the forest made it adequately clear that living nature was the source of light and air, of food and water.

As Tagore wrote in The Religion of the Forest," the ideal of perfection preached by the forest dwellers of ancient India runs through the heart of our classical literature and still influences our minds. The forests are sources of water and the storehouse of a biodiversity that can teach us the lessons of democracy; of leaving space for others whilst drawing sustenance from the common web of life.

My own biological life and ecological journey started in the forests of the Himalaya. Trees have been my teachers from birth to the present.

My father was a forest Conservator, and my mother chose to become a farmer after becoming a refugee in the tragic partition of India and Pakistan. It is from the Himalayan forests and ecosystems that most of my learning of ecology took place. The songs and. poems our mother composed for us were about trees, forests and India's Forest Civilization.

My involvement in the contemporary ecology movement began with "Chick", a non-violent peaceful response to the large-scale deforestation that was taking place. Chipko means "to hug", "to embrace". Women declared that they would hug the trees, and the loggers would have to kill them before they killed the trees. In the 1970's, peasant women from my region in the Garhwal Himalaya came out in defense of the forests. Logging had led to landslides and floods, and scarcity of water, fodder and fuel. Since women provide these basic needs, the scarcity meant longer walks for collecting water and firewood, and a heavier burden. Women knew that the real value of forests was not the timber from a dead tree, but the springs and streams, food for their cattle and fuel for their hearth. The folk songs of that period said- "These beautiful oaks and rhododendrons, They give us cool water Don't cut these trees We have to keep them alive" In 1973, I had gone to visit my favorite forests and swim in my favorite stream before leaving for Canada to do my Ph.D. But the forests were gone, and the stream was a trickle.

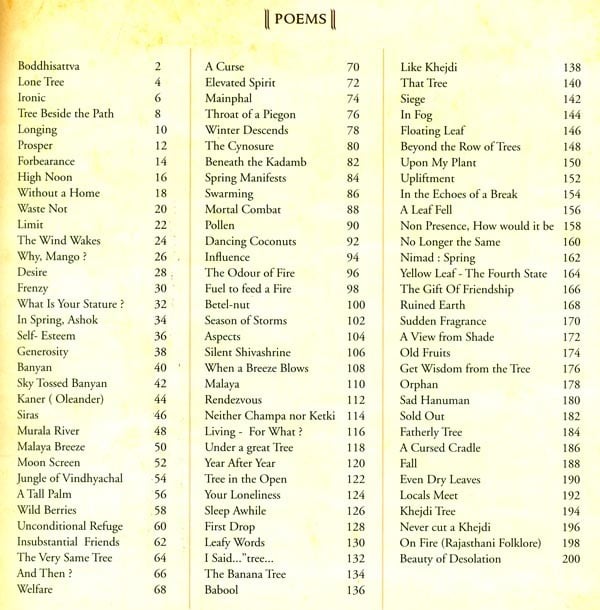

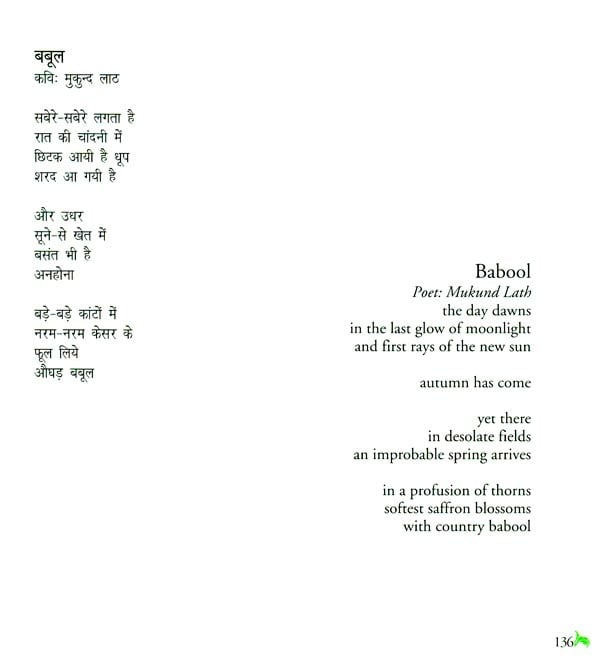

Book's Contents and Sample Pages