The Temple of Muktesvara at Caudadanapura (A Little-known 12th-13th Century Temple in Dharwar District, Karnataka) - An Old Book

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG560 |

| Author: | Vasundhara Filliozat |

| Publisher: | Indira Gandhi Natioal Centre for the Arts and Abhinav Publication |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1995 |

| ISBN: | 8170173272 |

| Pages: | 224 (Throughout Color and B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11 inch X 8.5 inch |

| Weight | 1.10 kg |

Book Description

About the Book

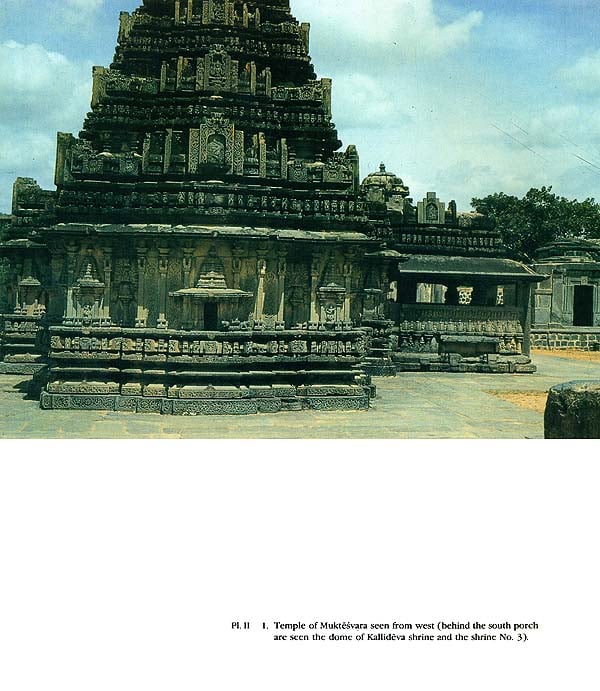

The northern part of Karnataka is one of the richest areas of India in monuments of great artistic value. It was subjected to the rule of several royal families, Calukyas of Kalyana, Kalacuris and Seunas in the 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th centuries A.D. which has been a period of great cultural refinement. It was the time of the greatest expansion of the Kalamukha-Lakulasaiva movements, and of the rise of Virasaivism. The temple of Muktesvara at Caudadanapura (Dharwar District) is a beautiful representative of the style and the high culture of that time. Its history is known to us thanks to a set of seven long inscriptions, composed in literary medieval Kannada, engraved with great care on large steles. They provide informations on the local rulers, kings of Guttala who claimed a Gupta ascendancy, on some constructions in the temple complex, on diverse donations to the deity, and very interesting details on a few prominent religious leaders. It introduces to us Muktajiyar, a Lakulasaiva saint, and Sivadeva, a Virasaiva saint, who entered the place on the 19th of August 1225 and led there a long life of renunciation, asceticism and spiritual elevation. The legacy of this age of intense Saivite faith is a jewel of architecture and sculpture. It is a single cella temple in what is popularly known as Jakkanacari style, sometimes called Kalyana-Calukyan style, which is not appropriate, as many temples of the same style have also been built under the patronage of Kalacuri or Seuna dynasties. The present study contains a historical introduction, the complete edition, translation and interpretation of the inscriptions, an architectural description, with a graphic survey, and an iconographical analysis.

About the Author

Vasundhara Filliozat, born in Haveri, Karnataka, holds a master's Degree from Karnataka University, Dharwar, and a Ph.D. from Sorbonne, Paris, France. From 1972 to 1984 she worked on many aspects of history of the Karnataka kings who ruled from Hampi-Vijayanagar. From 1985 onwards she works on the temples of Jakkanacari style in the Dharwar District of Karnataka. She is a free-lance historian and epigraphist. Her fields of interest extend upto dance, music, drama and literature. She has published a number of books and articles in Kannada, English and French on Hampi, history of Karnataka, Indian music and drama, Kannada and French literature.

Forword

"The Temple of Muktesvara at Caudadanapura", a monograph incorporating the studies undertaken by Vasundhara Filliozat at her own initiative, has been included in scheme of publications of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) under the Kalasamalocana series for its significant contents concentrating on regional structural and cultural idioms in the context of Karnataka. The IGNCA views the regional architectural tradition of India as the basic source of any artistic expression; and such an approach becomes highly relevant in regard to a particular shrine or group of shrines which have not been analyzed in the light of available evidence of Vastu and Agama texts. Thus, in this respect the Muktesvara temple at Caudadanapura (District Dharwar), which is associated with Virasaivism as a living shrine, makes an ideal choice.

IGNCA is aware of the importance of the cultural heritage of Karnataka and has already brought out Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat's 'Svayambhuvasutrasamgraha', a Saiva agamic text, and will be publishing soon a monograph by Adam Hardy on the Karnataka temples. Vasundhara Filliozat's monograph on Muktesvara temple, devoted to and inspired by Virasaivism, may offer a different regional perspective on the subject combining cultural ethos, artistic creativity and spiritual idealism.

Perhaps on account of its moderate proportions and, relatively, an unpretentious character, in comparison with structurally conspicuous shrines of Karnataka cast in northern, southern and blended styles, the Muktesvara temple at Caudadanapura could not receive much attention of well-known art-historians. Some references, no doubt, are available to the temple in the older publications, yet these do not cover all the necessary details. The inscriptions at the site, however, have been deciphered and studied but only limited attempts seem to have been made to analyze them in the context of the shrine under reference, without much relevance to the textual traditions. Built in the twelfth century A.D., the Muktesvara shrine at Caudadanapura is a living temple with Virasaiva affiliations and preserves a long standing tradition of rites and rituals.

We are thankful to Vasundhara Filliozat and Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat, reputed Indologists and Sanskritists, who have authored the present monograph, for undertaking integrated and detailed investigations on this little-known shrine covering the history, epigraphs, architecture, iconography and local religious (Virasaiva) traditions and agamic concepts. The monograph is intended to present, relatively, an integrated picture of various aspects of the Muktesvara temple in the light of the sources available including those connected with Virasaivism. The epigraphical material available throws interesting light on the Pasupata and Virasaiva traditions as also its interface with more crystallized and textually articulated agamic tradition.

It appears from an inscription (Inscription I, p. 27) that the Muktesvara temple was built under the influence of Pasupatas with possibly sabhasma dvijas (brahrnanas smearing ashes on various parts of their body) serving as priests under the Saiva yogins. While the brahmanas recited sacred hymns using seven notes like the Stimaveda and chanted the Gayatri hymn and the sacred Sadaksari (Siva) mantra (Om namah Sivaya) to .propitiate the Lord and offered tarpana as a part of daily puja to the God, rsis (sages=gurus) and the directions; the yogins (pasupatacaryas) were engaged in the practice of (Hatha) Yoga using diverse sitting poses like padmasana, vajrasana and svastikasana and followed different precepts like nadabheda, bindubheda, saktibheda and atmabheda as a part of some specific system, in their sadhana.

Initially, the temple under reference, although of Pasupata (Saiva) origin, recognized and accepted some elements of Brahmanical tradition in regard to certain rituals as evidenced by inscriptions and iconographic representations. Possibly the system underwent some modification, under a puritanical Virasaiva saint (siddha) Sivadeva who arrived at this site, i.e., Muktiksetra, around the middle of the year A.D. 1225 and introduced some amended or purified system of worship in the temple. According to the epigraphical references, he (Sivadeva) chased and dispersed the trembling bhutas (evil spirits) and pounded Bhairava (Inscription III, p. 49). He has also been mentioned as the one who destroyed the prestige of those who worshipped other (than Siva) gods, and that he carried nothing else but his overflowing weight of devotion to Siva (Inscription V, p. 74). Such expressions suggest that on account of his great devotion to Siva , with the knowledge of Siva-tattva, he might have prevented the priests to make offerings to various deities like bhutas and Bhairava, as a part of the vighnotsarana kriya and giving bali (offering) which is a normal item of Hindu puja tradition to make the ritual free from obstructions. Sivadeva appears to have rightly discarded the system with a spirit of total surrender to the Supreme Lord, i.e., Siva. It is not unlikely that the Saint might have even simplified the rituals as a staunch follower of the doctrines of Virasaivisrn.

The Muktesvara temple according to the local tradition symbolizes Kailasa, the eternal abode of Siva and his divine assembly. An inscription (III, p. 48), although Virasaiva in character, explains the concept beautifully: 'the excellent Tungabhadra is a divine river, the congregation of the brahmanas is the assembly of gods, the temple of Siva is Meru making thus the Muktiksetra like Kailasa on the earth.'

The linga installed inside this shrine is regarded to be a svayambhu-linga representing Siva with his own consciousness (creative power). The concept could be better understood in the light of a reference in Kriyasara of Saivacarya Nilakantha (circa 1400 A.D.), quoted by Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat, which reads as under:

Prthivyantargatah sambhurbijam vainadarupatah /

Sthavarankuravadbhumim-udbhidya vyakta eva sah //

[Translation: Sambhu inside the earth is like a seed in the form of nada, simulating an immobile germ, which bursts from the ground and becomes manifest.]

The Virasaivas of Karnataka do not seem to have totally discarded pre-Basava concepts and elements of the main stream of Hindu thought including the sacredness of the Vedas and Sastras and recognized even thirty gods of Vedic origin. It appears that there was a constant flow of ideas from one part of India to the other, and it is on this account that poet Banabhatta's invocatory verse from Harsacaritam (I.1), a non-religious text, reached Caudadanapura where it has been used as mangalacarana in four out of eight epigraphs perhaps for the reason that it preserved the concept of Siva as a cosmic column:

Namastungasirascumbi-candracamaracarave /

Trailokyanagararambhamulastambhaya sambhave //

Preface

A temple dedicated to a great Hindu God is the product, not only of a technical knowledge of building, but also of metaphysical and theological concepts, of artistic and literary culture and of characteristic religious practices and attitudes. We possess a revealing literary documentation on all these aspects. That which may be useful for the study of the temple of Muktesvara at Caudadanapura is naturally circumscribed in works of Saivite inspiration, as it is a monument dedicated to Siva, erected by individuals inspired by the ideals of this religion and belonging to communities who characterise themselves by the pursuit of these ideals. It belongs to a period of transition in the history of Saivism in Karnataka, i. e. the 12th and l3th century when the predominant Pasupata and Kalamukha movements were gradually integrated in what was to become the Virasaiva faith inspired by Basava. The prevalent Saiva literature of that time, in. that region, is the Saivasiddhanta school of Tantras and of course the first period of Virasaiva literature, which appears itself as deeply rooted in the Tantric and Puranic lore.

The Saivasiddhanta Tantras are-claimed as scriptural authorithy by the Saiva communities of that time in Karnataka The Vatulasuddhagama, a version of the last text in the consecrated list of twenty-eight Agamas has always been held in high reverence in this group. There are also Sanskrit Virasaiva compendia of Saiva concepts, tenets and practices, such as the Saivaratnakara of Jyotirnatha (c. 1100), the Viramahesvaracarasamgraha of Nilakantha Naganatha (c. l300), the Kriysssre of Nilakantha Sivacarya (c. 1400). They contain a host of quotations from the same Saivasiddhanta Agamas and from Puranas. References to Vedic scriptures come only in the latest of these works.

These diverse communities, their organized religious institutions, their pontiffs and heads, are known to us through allusions in inscriptions found in the precincts of the temples. These inscriptions contain also references to agamic sources, sometimes direct quotations. They express many facts of the religion, ideas about the deities, about the abodes offered to them on earth in the form of temples. The inscriptions and their tantric background are, indeed, the best source for the correct understanding of a Hindu temple.

The present study is based on the direct observation of the monument and remains on the site, on inquiry with all those who are to-day concerned with the life of the temple, descendants of the founder, villagers etc., on the examination of the inscriptions and on research in the literary sources. It aims at collecting and correlating informations of different sources. The section on history places the monument in its historical setting. The full text of the inscriptions is given and a translation is proposed. That appeared as an attempt to be done. These inscriptions provide the most authentic material about the temple. They are also refined literary pieces. And it appears necessary to correlate this poetic art with the plastic art of architecture and sculpture. Both, the inscribed chart and the monument, are objects of beauty, products of a same culture. The unity of this culture is based on philosophical and religious concepts, the origin of which we have searched in Sanskrit Tantric, Puranic and Virasaiva literature. The section on architecture includes an attempt to correlate the philosophical concepts of God and the world with the proper architectural forms and spaces. A brief description of particular features has been given, only to indicate the general structure of the monument. Features of style have not been studied as such. Any study of a temple style implies comparison of as many samples and items as possible. At the present stage it cannot be conducted satisfactorily, because the high number of later Calukyan temples has not yet been systematically surveyed and very little material is easily accessible. In spite of the pioneering work done by Cousens and others the survey is still at its initial stage. The section of iconography is also shortened for the same reason.

The sections on history, epigrapghy and iconography are authored by Vasundhara Fillic.zat; the architecture has been dealt with by Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat.

The period of construction of the temple of Muktesvara has been the thirteenth century, when a saintly figure, Sivadeva, inspired the religious life by his faith and his actions. His memory has been preserved in the inscriptions. The temple is still a testimony to the grandeur of the religion and art he inspired. His memory is also kept alive by a family in which are traditionally selected the heads of the local Virasaiva Matha and which claims Sivadeva himself as its most famous member. We had the good fortune to get our first acquaintance of this temple and of Sivadeva, through Sri Sadashiva Wodeyar, former Vice-Chancellor of Karnataka University, Dharwar, who not only gave us hospitality, informations, but also demonstrated to us the profound feeling that this holy place and monument raise in the heart of the Virasaivas. He invited us to work on the site in his family home, where his father, Shivadeva Wodeyar lived in retirement, like the saint of yore. They both helped us in many ways, with friendly services as well as with informations. We regret very much that Shri Shivadeva is no more in this world to see this book, which he wished so much to help. Like his predecessor Saint Sivadeva, our Ajja also left this world to enter that of Siva as a nonagenaire. We evoke his memory with reverence and nostalgy. We extend our most hearty thanks to Sri Sadashiva Wodeyar and to all those in his entourage who helped us and sympathised with our work. We have a special debt of gratitude to Professor K. Krisnamurthy who has explained us difficult poetical passages of inscriptions and thanks to whom our translation was greatly improved. Our special thanks are due to my guru, Dr. G. S. Dikshit, for his timely advices and suggestions.We have a thought for all those whom we consulted like Drs. M. M. Kalburgi, Raghunath Bhatt, Katti from Karnatak University, Dharwar, and who gave us willingly precious informations. Also we will not fail to remember the participation of Mr. Basavaraj and Mr. Hiremath, two students of architecture and our daughters Miss Manonmani and Bhamati at the initial stage of this work. We will no forget to evoke the precious advice given by Prof. K. R. Hayagreevachar and his better half Vanamala Achar; both,:being professors of English, went through the first draft of this text and gave us some valuble hints to improve our style of English. We also express heart felt gratitude to The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New-Delhi, for accepting to make our work available to the world of scholars and indologists.

We lack in words to express our heartfelt gratitude to Dr. (Mrs.) Kapila Vatsyayan, Academic Director of IGNCA, New Delhi, for accepting to publish this work. We thank also Mr. M.C. Joshi, Ex-Director General of ASI, now Member Secretary of IGNCA, for his valuable suggestions and finally Dr. Lalit Gujral of IGNCA for making our work available to the world of scholars and indologists in a short time.

Contents

| Preface | I | |

| Contents | V | |

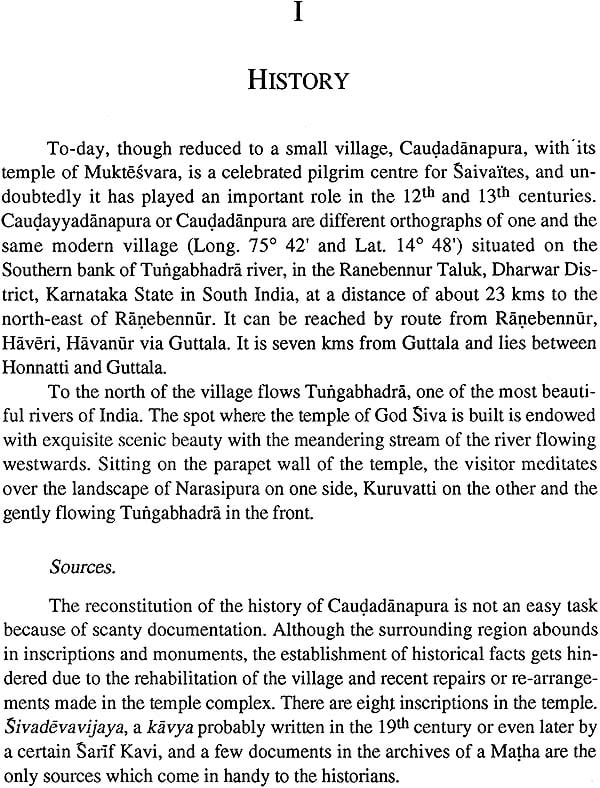

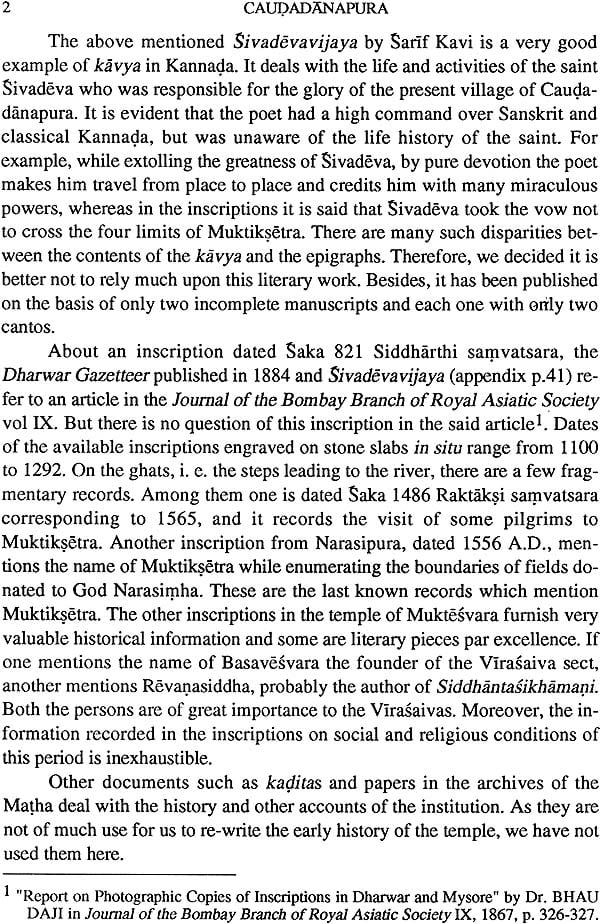

| I. | History | 1 |

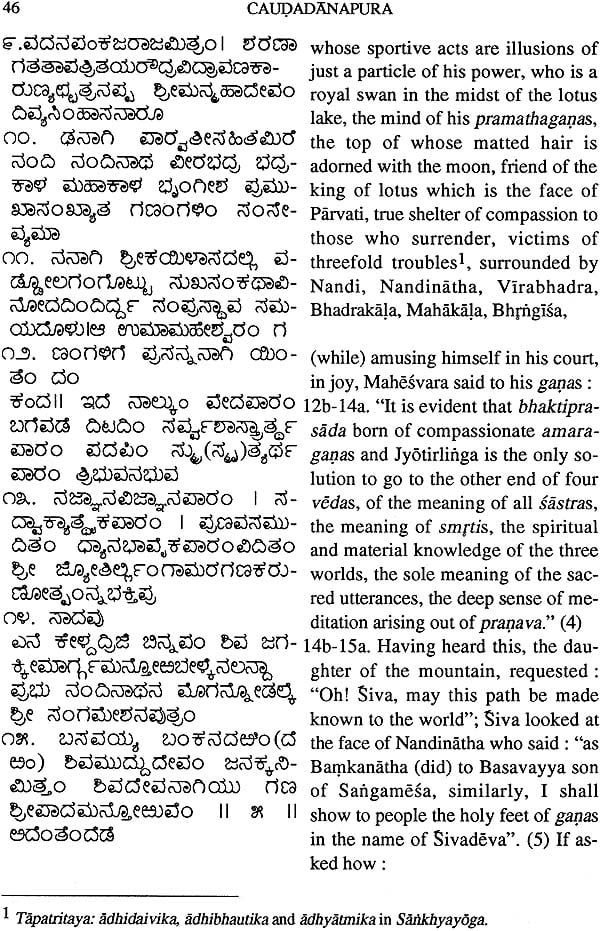

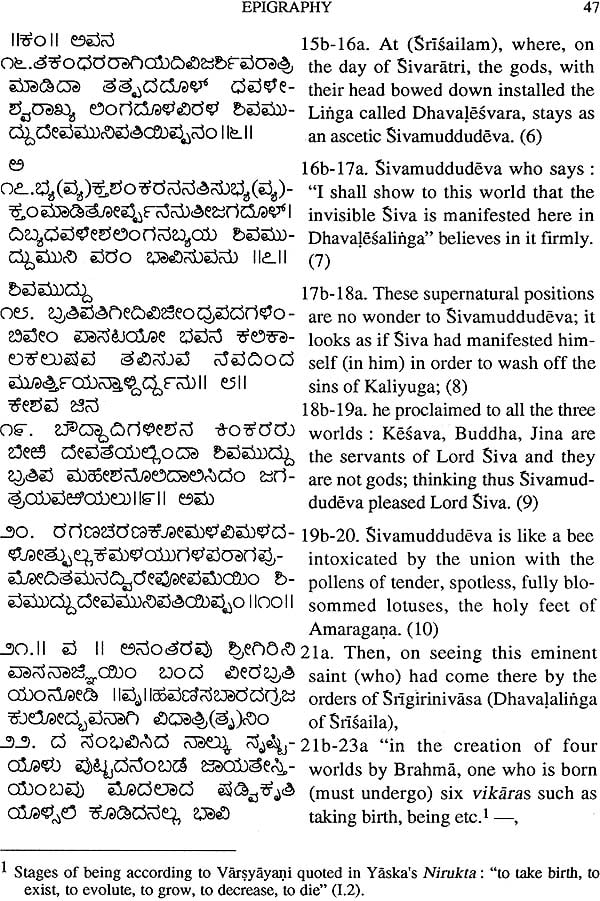

| II. | Epigraphy | 17 |

| Inscription No. I C. 1100-1120. | 18 | |

| Inscription No. II Saka 11 A.D. 1198. | 31 | |

| Inscription No. III | 43 | |

| Inscription No. IV | 56 | |

| Inscription No. V | 71 | |

| Inscription No. VI | 77 | |

| Inscription No. VII | 83 | |

| Inscription No. VIII | 87 | |

| Fragmentary Records | 90 | |

| III. | Architecture | 93 |

| General description | 93 | |

| A. | The minor structures | 96 |

| B. | The main monument | 98 |

| The theological concept | 98 | |

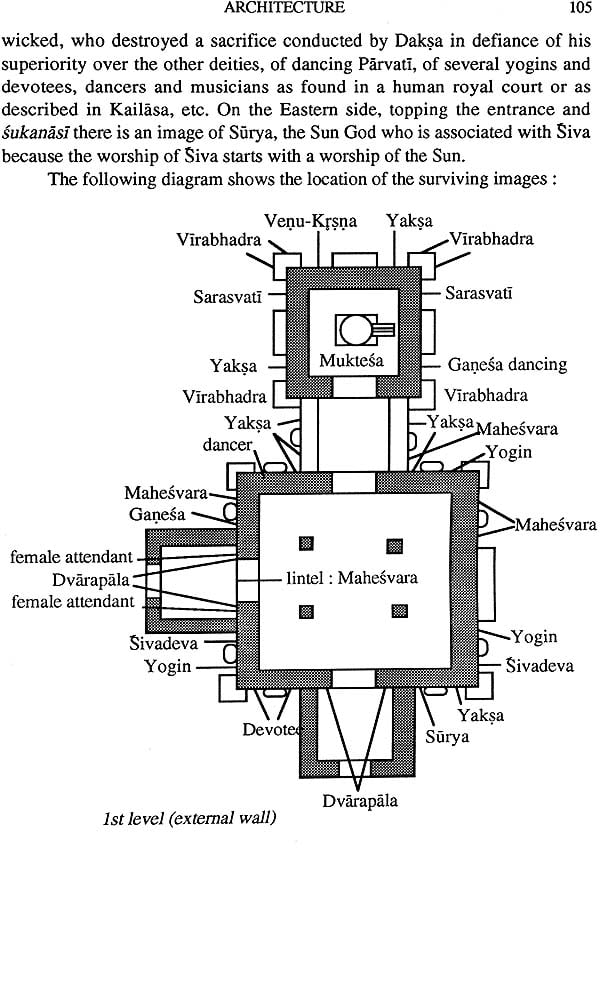

| The architectural concept | 104 | |

| 1) | The main structure (vimana) | 108 |

| a) | The base (upapitha) | 109 |

| b) | The wall (pada) | 110 |

| c) | The entablature and eave (prastara) | 111 |

| d) | The superstructure | 112 |

| e) | The dome-shaped roof | 113 |

| 2) | The antechamber (sukanasi) | 113 |

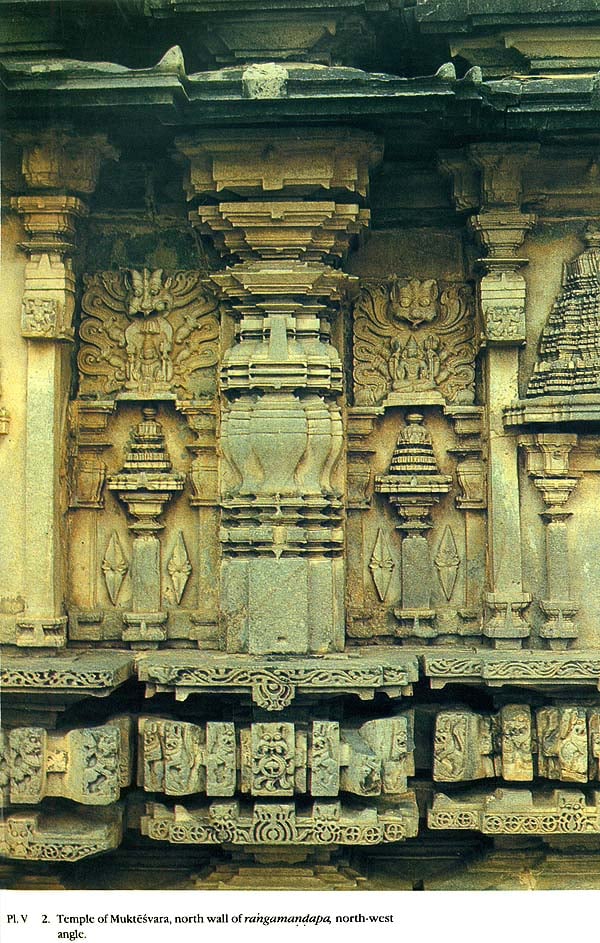

| 3) | The rangamandapa | 113 |

| 4) | The miniature secondary structures | 115 |

| 5) | Composition of the miniature secondary structures | 116 |

| IV. | Iconography | 119 |

| Inside the temple | 119 | |

| Outside the temple, walls and tower | 121 | |

| Appendix 1. Transliteration of inscriptions in nagari script | 127 | |

| Appendix 2. Transliteration of inscriptions in latin script | 151 | |

| Bibliography | 177 | |

| Genealogy | 179 | |

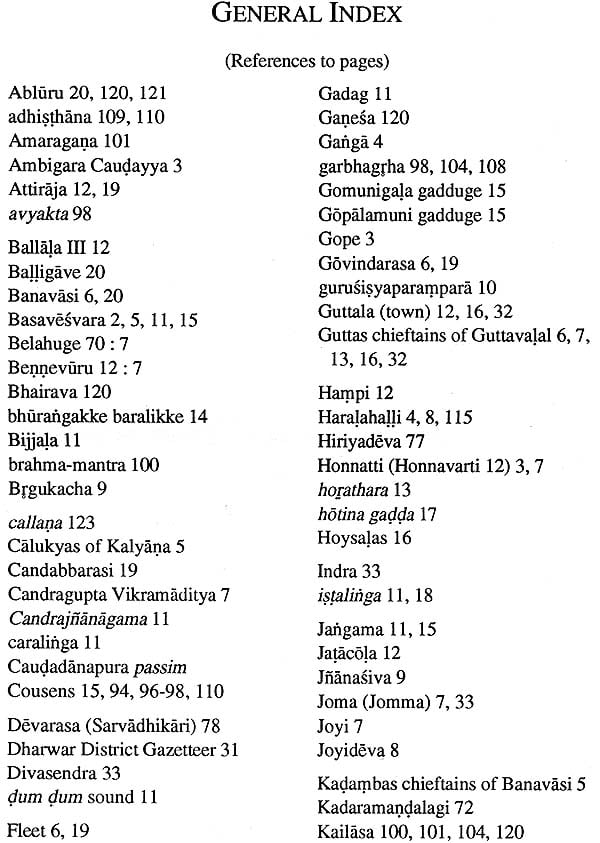

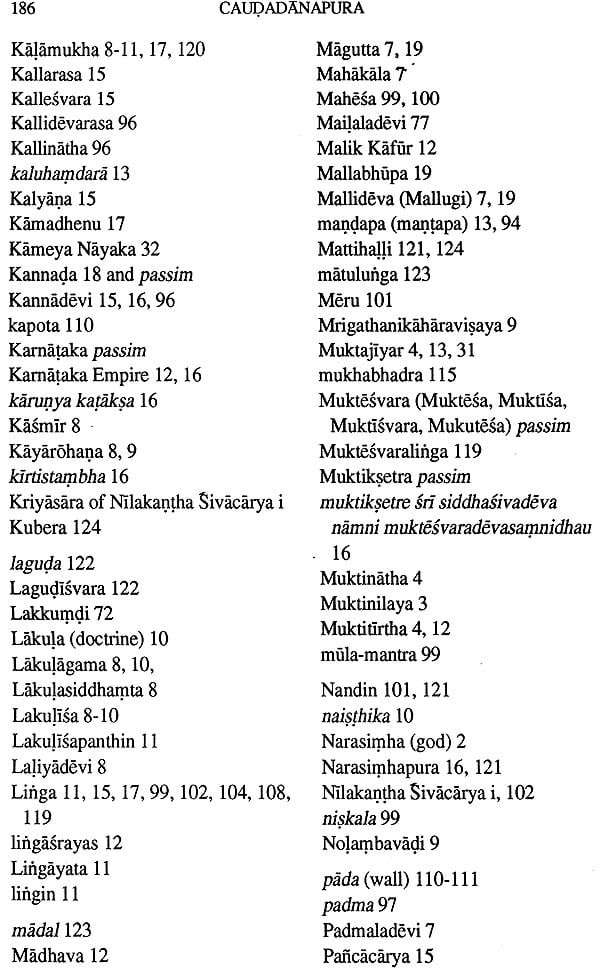

| Index to the inscriptions | 181 | |

| General index | 185 | |

| List of plates | 189 |