Vajrayana Images of the Bao-xiang Lou (Pao-hsiang Lou) (In Three Volumes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDC023 |

| Author: | Fredrick W. Bunce |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Edition: | 2009 |

| ISBN: | 9788124604809 |

| Pages: | 1088 (Illustrated Throughout In B/W) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.9" X 11.9" |

| Weight | 10.10 kg |

Book Description

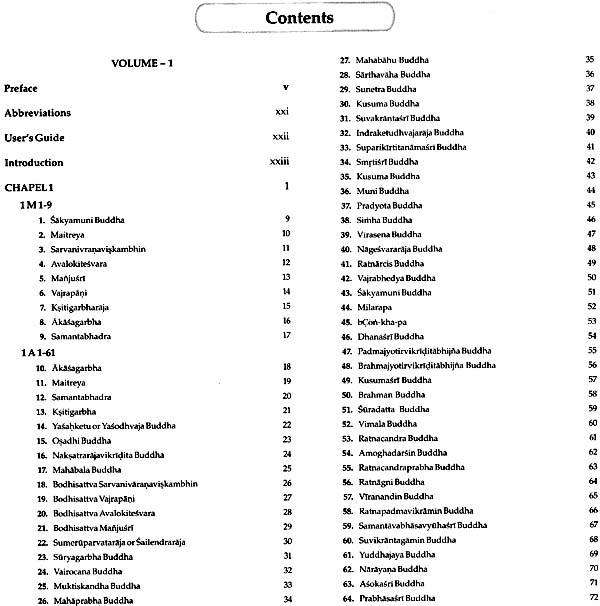

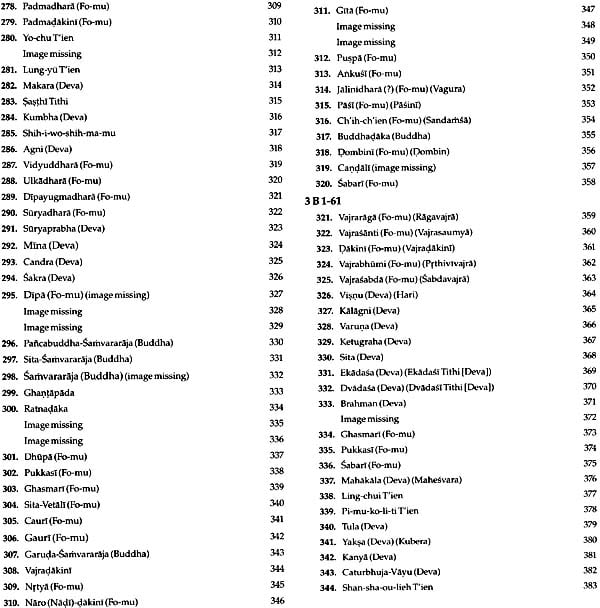

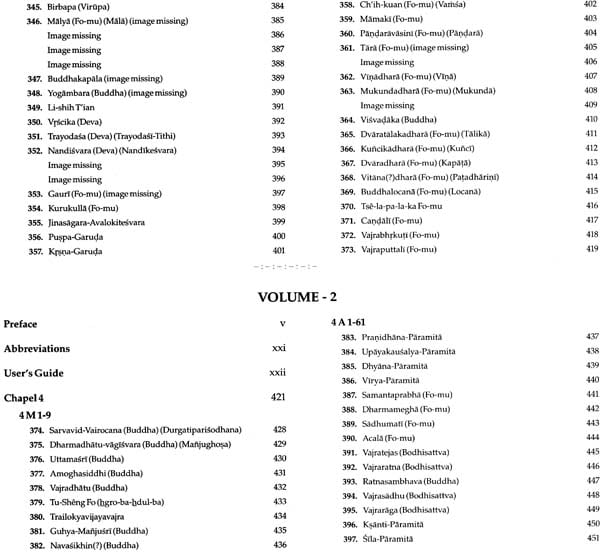

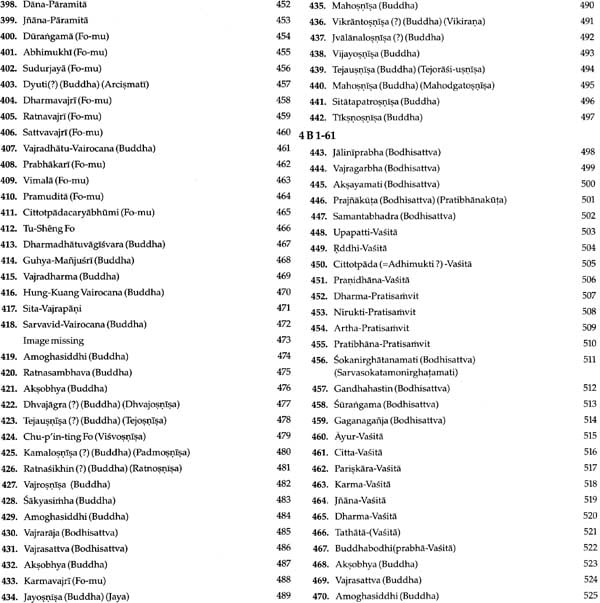

The Three volumes contain an iconographic analysis and compilation of the over 760 images from the six chapels of the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) in the garden of the Tzu-ning Kung (Palace of Kindness and Tranquillity) in the Forbidden City, Beijing. The pavilion Pao-hsiang Lou, a two-storied simple structure with seven chapels on each floor, holds hundreds of Tibetan Buddhist images of remarkable quality. The volumes present the entire set of images, each reproduced and explained with great clarity. There are details of each image with regard to the physical description of the figure portrayed and its various iconographical and stylistic features and associated images. Each entry contains the name of the deity with the Sanskrit, Tibetan and Chinese transliterations of the name. The very interesting and useful introduction discusses deities of mandalas, placement of deities within a single chapel, images of the Pao-hsiang Lou pantheon compared to the Chu Fo P u-sa Sheng Hsiang Tsan pantheon, variations in depiction of images with regard to their hair, crown and other parts and associated ornaments, and the asanas of the images. The scholarly volumes are a result of the painstaking research by the author by referring to noted experts on the subject.

The volumes will interest all students and scholars of Buddhist art and iconography.

Fredrick W. Bunce, a PhD a cultural historian of international eminence, is a authority on ancient iconography and Buddhist arts. He has been honoured with prestigious awards/ commendations and is listed in Who's Who in American Art and the International Biographical Dictionary, 1980. He is currently Professor Emeritus of Art, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, Indiana. He has authored the following books all published by D.K. Printworld.

· Buddhist Textile of Laos, Lan Na and the Isan - The Iconography of Design Elements.

· A Dictionary of Buddhist and Hindu Iconography.

· An Encyclopaedia of Buddhist Deities, Demigods. Godlings, Saints and Demons (2 vols.).

· An Encyclopaedia of Buddhist Deities, Demigods. Godlings, Demons and Heroes (3 vols.).

· The Iconography of Architectural Plans A Study of the Influence of Buddhism and Hinduism on Plans of South and South-east Asia.

· Islamic Tombs in India The Iconographical and Genesis of their Design.

· Monuments of India and the Indianized States.

· The Mosques of the Indian Subcontinent Their Development and Iconography.

· Mudras in Buddhist and Hindu Practices An Iconography.

· Numbers Their Iconographic Consideration in Buddhist and Hindu Practices.

· Royal Palaces, Residences and Pavilions of India An Iconographic Considerations.

· The Sacred Dichotomy: Thoughts and Comments on the Duality Female and Male Iconography in South Asia and the Mediterranean.

· The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and Deities A Unique Pantheon.

· The Yantra of Deities and their Numerological Foundations An Iconographic Consideration.

In 1986, after a trip to Nepal and the purchase of the first of many thangkha, I was present with a book from my friend and colleague, Professor of Anthropology, Dr. Hildegard Pang, Indiana State University. This publication was to become important to me in so many different ways! It, of course, was the 1965 reprint of Walter Eugene Clark's Two Lamaistic Pantheons. It represented a gold mine of Indo-Tibetan-Sino deities i.e. 766 reproduced images and/or bases from the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) and 360 illustrations from the Chu Fo P'u-sa Sheng Hsiang Tsan (Zhu Fo Pu-sa Sheng Xiang Zan). In addition Clark including: a "Sanskrit Index," a "Tibetan Index," and a "Chinese Index" (Wade-Giles transliteration).

I made extensive use of this publication in the compilation of: An Encyclopaedia of Buddhist Deities, Demigods, Godlings, Saints and Demons: With Special Focus on Iconographic Attributes. However there were certain problems involved. My main interest was, and still is: iconography. Unfortunately the illustrations, both of the three-dimensional images and the two-dimensional wood cuts (xylographs), were quite small and the identification of certain objects was virtually impossible at times. This, in part, was due to the quality of printing, at the time of the 1965 reprint, as well as the size of the individual illustrations. I scoured available visual and written (English, primarily) sources so as to ascertain and/or identify a particular image in the hand of a particular deity. However, attempting to identity certain objects through cross-checking with other pantheons and/or references, both verbal and visual, was likewise, unproductive. In addition, an iconic object held by a certain deity may vary from pantheon to pantheon, and/or from image to image. There ended up numerous iconographic forms that simply could not be identified visually.

Then, on trip to India in 2001, I met with Dr. Lokesh Chandra, after having corresponded with him. During that afternoon's conversation, he mentioned that he had in his possession a set of negatives were of the Chu Fo P'u-sa Sheng Hsiang Tsan (Zhu Fo Pu-sa Sheng Xiang Zan). At that time he produced a large, photographic positive of one of the icons. It was, of course, far clearer than the same illustration in Clark's important volume (mine being the 1965 half-tone reprint of the 1937 edition). The objects held in the deity's hand were relatively clear and easily identifiable. He then suggested that it might be of value to reissue this unique pantheon in a large format and with accompanying icono-graphic delineation. Hence: Lokesh Chandra and Fredrick W. Bunce. The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and other Deities: A Unique Pantheon.

In the intervening years, my interest in iconography has primarily been directed toward architectural plans i.e. The Iconography of Plans: A Study of the Influence of Buddhism and Hinduism on Architectural Plans of South and South-East Asia (2002); Islamic Tombs in India: The Iconography and Genesis of Their Design (2004); and forthcoming Royal Places, Residences and Pavilions of India 13th through 18th Centuries An Iconography Consideration (2004); and the article: "Kalakalpa": Journal f the Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts, "Maha-Vihara dharmapala: Its Descendents" (2004). However, partially via a correspondence with my publisher and another conversation with Dr Lokesh Chandra, my interest in the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) was rekindled, maybe even refocused.

Dr Lokesh Chandra suggested that we collected again, this time on the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) Pantheon reproduced in Clark. Unfortunately, unlike the Chu Fo P'u-sa Sheng Hsiang Tsan, he was not in possession of a set of negatives of the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) Pantheon. The images in WEC, we agreed, were not clear, and at best, confusing in their half-tone printing. He then showed me his copy of the 1937 edition which he owned. There, the printing process i.e. photogravure produced far superior definition to the images and their symbols. Soon after, he kindly loaned his 1937 edition to the publisher, D.K. Printworld, to be computer scanned. The results were quite acceptable when enlarged.

As often times happens, scholars make notes in the margins of the books in their possession. Dr. Lokesh Chandra's 1937 edition was rife with pencilled notations e.g. NSP designations and numerous re-identifications. In that respect, it was a gold mine.

I then, in the spring of 2004, began preliminary work on an iconographic analysis and compilation of the 766 images from the six chapels of the second store of the Pao-hsiang (Bao-xiang Lou) as my contribution. Unfortunately, Dr Lokesh Chandra found it necessary to withdraw from the collaboration. Nonetheless, his knowledge and input is of a passive nature as I made extensive in the re-identification of a number of images.

Also, at that time, I contacted the Harvard-Yenching Institute at Cambridge, Massachusetts, to ascertain whether they had either negatives or photographic positives of this pantheon. This I did with the objects of obtaining either negatives or positives and permission to reissue these illustrations in a larger, more readable format. The object was to present work in which the photographed images of the Bao-xiang Lou were again reproduced, but in a larger format-i.e. one image per page.

My approach to the work at hand is basically visual. My early training was in the fine Arts-i.e. painting and sculpture. In this, I had developed a trained eye to discern differences, as well as similarities and comparisons. This has stood me in good stead when I entered my years as a PhD candidate. I found that my visual acuity of analysis "dovetailed" with the academic/scholarly approach that my degree in Comparative Arts required. Arts required. At that time, my interest was in Western iconography, specifically French; hence my dissertation: The Parallel Forms of Erotic Painting and Poetry in the Sixteenth Century French court.

Little did I realize that a sabbatical in Asia would completely refocus my interests and direct them towards the iconography of the East! Assembling a compendium of major Buddhist and Hindu iconographic objects was instituted for my own use after the above-mentioned purchase of three, especially fine thangkhas by the Tibeto-Nepali artist Karma Thupten (aka Karma Lama) in Kathmandu. Isolated volumes were scoured to glean the necessary information regarding the myriad objects. I had to immerse myself into the basis of Theravada and Mahayana including Vajrayana and/or Mantrayana Buddhist philosophy and practice. It became an all-consuming quest!

It would have been beneficial, to a point, had a reading knowledge of Sanskrit and/or Tibetan and/or Chinese, or all three. But, alas, I did not. I certainly do not denigrate the scholarly approach which focuses upon the literature. However, my approach, quite naturally, was visual, and time to learn these important languages was not a luxury I possessed. At the time, I realized that if I were to continue, my focus had to be visual, primarily, and, so it has been! Nonetheless, my immersion in this area has afforded me a very rudimentary knowledge, or a least, acquaintance with Sanskrit and Tibetan through transliteral equivalents.

There are three major reasons why such a reissue is important. First, the presentation of the images in a format which makes their detail visually readable. Second, the presentation of accompanying analysis and/or listing of the individual iconographic elements which, sadly, was lacking in the original publication(s). Third, even though a part of this important pantheon was first published in 1937 and reprinted in 1965, it felt this study may refocus attention on these images and renew interest in them. Finally, I hope that this, publication will provide keys for other researchers to unlock doors and give us all-important glimpses into the rich culture from which these images grew. This, then, in addition, to create an interest in the large numbers yet to be seen by the public at large of the lower chapters of the lower chapels of the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) as well as all the images of the Chi-yun Lou (Ji-yun Lou).

The names that were employed by Clark appear as the headword entry for each image (deity). These are immediately followed by the numeric position that the image holds within Clark's work within parentheses. It is to be noted that the presiding deity, as Clark saw, appears out of sequence. He is given a full page at the beginning of each chapel section. Then three transliterations, if known: Sanskrit, Tibetan and Chinese. If there are variations of the names, these will be noted here e.g. for the Suvakrantasri Buddha, Tib.: Sin-tu-rnam-par-gnon-pa or rGyal-ba Sin-tu-rnam-par-gnon-pa. If there is a re-identification, this also will be noted here in parentheses e.g. Ind.: Dandadhara Yo-mu (yamadandi). The Wade-Giles is the transliteration Clark used, and that appears first followed by parentheses in which the Pinyin transliteration appears e.g. Chi.: Hung-yen Ti-ch'uang-wang Fo (Hong-yan Di-chuang-wang Fo). And, lastly, the Clark location designation will appear e.g. 2B7.

The forbidden City (Gu-gong), Beijing, is undeniably one of the most remarkable palace complexes in the world. Vast, labyrinthine, forbidding, elegant and luxurious are but meagre adjective attached to this palace ensemble. In sheer scale it is peerless. it mirrors the incredible resources that the Chinese Emperors had at their disposal, especially during the periods that the capital was in Beijing.

The Forbidden City possesses great halls of incomparable elegance, magnificent vistas to startle the eye, massive squares to awe the common man, avenues, alleys, gardens tucked away, smaller palaces of quiet beauty, numerous attendant structures in abundance, meandering streams and placid lotus ponds (seen Plate 1). For all its individual parts, it, nonetheless, presents a cohesiveness and singleness of mind.

Bao-xiang Lou and Environs

Hidden away in this maze of byways and courts on the west side of the Forbidden City is the Tzu-ning Kung (Ci-ning-Gong) (Palace of Kindness and Tranquillity) and its attendant temple garden the Tz u-ning Yung (Ci-ning Yung) (Garden of Kindness and Tranquillity) (seen Figure 1). This "smaller" palace is said to have been the residence of the Dowager Empress Hsiao-sheng, wife of the Emperor Yung-cheng (young-sheng) and the mother of Hung-li (Hong-li) who became Gao Zong Zhun Dai Shang Huang Fa, or the Emperor Ch'ien-lung (Quian-lung). She was a devout Buddhist and received numerous gifts from her son during her long life, particularly on her decade birthdays i.e. 50th, 60th, 70th and 80th. The image reproduced in W.E. Clark are part of the Emperor's gifts to his mother, the Dowager Empress. The partial list of the Emperor's gifts is impressive, indeed. In 1751, for her sixtieth birthday she was gifted with "one set of Buddhas, and a complete set of Amitayur Buddhas." Her seventieth birthday, a birthday which for the Chinese is particularly auspicious as it is the result of the sacred seven multiplied by the complete ten, saw an impressive array of gifts i.e." nine sets of Amitayur Buddhas totaling 900 status, nine sets of the same totaling 9000 statues, nine Buddhas, nine Amitayur Buddhas, nine bodhisattvas, nine fo-mu, eighteen lo-han, and nine Buddhas." Nine is also particularly important and auspicious as it is considered to be a magnification of the sacred three as well as a number of good fortune and the numeral ten, as in the ten sets, indicates completeness. The list for her eightieth birthday has not been found, but it may have included the images found in the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang) since they are not mentioned or part of the gifts for her sixtieth or seventieth birthdays.

The "garden" of theTz'u-ning Kung (Ci-ning Gong) (Palace of Kindness and Tranquillity) to the south contains "a building known as the Hsien-jo Kuan (Xian-ruo Guan)," a temple flanked by two buildings, important for their contents but architecturally quite unremarkable i.e. the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) to the west and the Chi-yun Lou (Ji-yun) to the east. The Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) and its twin is a two storied, simple structure with seven rooms or chapels on each floor (see Figure 2). It was stated that this pavilion i.e. the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) held literally hundreds of Tibetan Buddhasimages of remarkable quality on both floors. This "temple" was arranged with seven room of the second story held a large image of the Mahaguru Tsongkhapa (Tib.: bCon-kha-pa) also known as rje Rin-po-che ("The Precious Lord of Teaching") the founder of the dGe-lugs-pa sect. In addition, the other structure i.e. the Chi-yun Lou (Ji-yun Lou) is said to be "filled from top to bottom with Tibetan Buddhas." Further, each chapel was so arranged as to contain a central altar with nine images, a "cabinet" to the right (to the left of the deities on the altar) with sixty-one images, apparently contained in "boxes." Another similar cabinet was set to the viewer's left (to the right of the deities on the altar) with the same number of "boxes".

Photographing the Bao-xiang Lou

The renowned Baron A. von Stael-Holstein having received permission from palace authorities to photograph the images within these two pavilions, undertook his important work between December of 1926 and February of 1927. The photographs were taken under the supervision of Benjamin Marsh. The Documenting and photographing of the image within the seven rooms or chapels of the upper story of the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) von Stael-HoIstein successfully oversaw and completed (see Figure 2). However, permission for any further photography was unilaterally and inexplicably withdrawn. The Baron von Stael-Holstein was, forthwith, invited to withdraw his photographic equipment and assistants for the Forbidden City. Unfortunately, the vast majority of Buddhas images seen by Lou (Ji-yun Lou) were, and still are, undocumented, un-photographed and/or unavailable to scholars and the public at large.

Later, in 1928, von Stael-Holstein magnanimously donated, among other items the photographic images of the upper floor of the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) to the Harvard Library. To date, scholars and students of Tibetan Buddhism who have not had the good fortune to visit the Forbidden City, much less the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) and/or the Chi-yun Lou (Ji-yun Lou) have only the partial photographic evidence of von Stael-Holstein's 1926-27 photographs to rely upon, and those either at Harvard University or within the volume of W.E. Clark.

Bao-xiang Lou Chapels

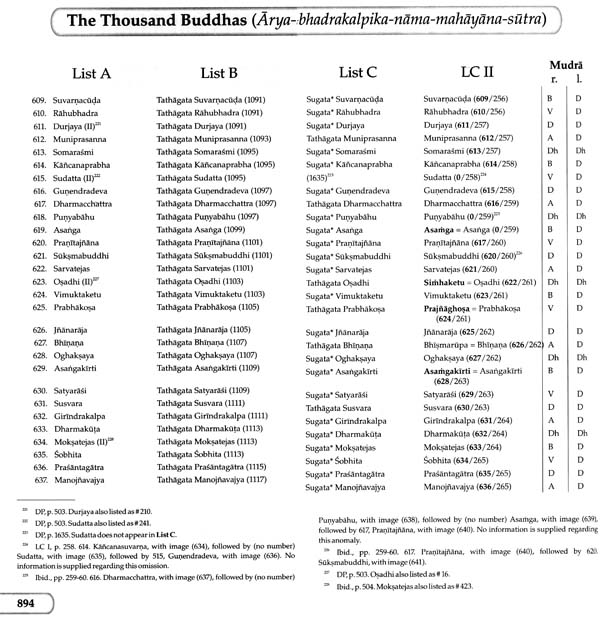

Seven interior spaces are designated by Clark as "chapels" within the upper storey of the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou). These seven open towards the east and the altars are against the western interior wall (see Figure 3). Against this west wall the images arrayed in three groups: 1) a central group, designated by WEC as "M," which possessed a central deity, the presiding deity of the chapel, and flanked by four deities to the right and four to the left or a total of nine images altogether in this ensemble; (2) a large group of sixty-one images to the central deity's right (the designation "right" refers to the right of the central group [M] as one faces as one faces the east), and (3) a group of sixty-one images to the central deity's left (the designation "left" refers to the left of the central group [M] as one faces the east). In this case, WEC rightly assigns the deities of groups A and B to the right and left of the central deity, respectively, based upon the alignment of the presiding deity i.e. facing east.

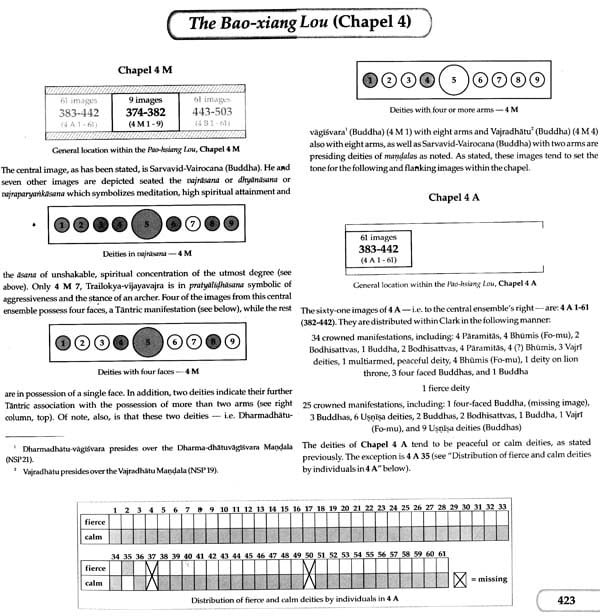

Frequently, those deities within the central ensemble i.e. 1 M, 2 M, 3 M, 4 M, 5 M, and 6 M are presiding deities within the NSP mandalas (see Appendix C), but not exclusively. In many cases the flanking deities of the central ensembles do not seem to appear in any of the NSP mandalas. The reason for this laudatory placement is yet to be explained. One interesting central ensemble is to be seen in 4 M. There Sarvavid-Vairocana (Buddha) (Durgatiparisodhana) (4 M 5) is the presiding deity for the Durgatiparisidhana Mandala (NSP 22.1). Dharma-dhatuvagisvara (Buddha) (Manjughosa) (4 M 1) is the presiding deity for the Dharmadhatu-vagisvara Mandala (NSP 21.1); and Vajradhatu (Bhuddha) (4M 4) is the presiding deity for the Vajradhatu Mandala (NSP 19.1). The deities Utamasri (Buddha) (4 M 2), Amonghasiddhi (Buddha) (4 M 3), Tu-Sheng Fo (hgro-ba-hdul-ba) (4 M 6), Guhya-Manjusri (Buddha) (4 M 8), and Navasikhin (Buddha) (4 M 9) are all peaceful, seated deities. The one singular exception is Trailokyavijayavajra (4 M 7) who is a fierce, standing deity.

Further, one would suspect that those deities to the right of the central ensemble would also have pride of place. However, in numerous chapels, attendant deities for a mandala are to be found to both the right and left of the central group.

The placement of the deities within a single chapel must have had some significance. It is possible that they may been inadvertently rearranged over the period of time since their original installation. Certainly the missing image seem to imply that the chapel were not sealed, or off limits, or not immune to the vagaries of time. These missing images do present many problems (see Figure 4).

Variations

When dealing with the two-dimensional images of the Chu Fo P'u-sa Sheng Hsiang Tsan (Zhu Fo Pu-sa Sheng Xiang) pantheon, it was surmised and noted that the woodcuts (xylographs) were product of more than one artisan. The three-dimensional images of the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) tend, upon initial examination, to be alike, and, indeed, in many aspects they are. However, after dealing with these images over a period of time, it became evident that there were subtle differences.

Variations-Bases

The two pantheons illustrated within Clark's Two Lamaistic Pantheons have a number of elements in common, as one would expects. As always, it is the dissimilarities that tend to me most interesting. Besides the obvious difference that exists between the three-dimensional and the two-dimensional representation, there is one variance that must be noted. In the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) pantheon, the images sit upon a single lotus throne (see Figure 5). However in the Chu Fo P'u-sa Sheng Hsiang Tsan (Zhu Fo Pu-sa Sheng Xiang Zan) pantheon i.e. the second illustrated Clark all the figures sit upon a double lotus throne (see Figure 6).

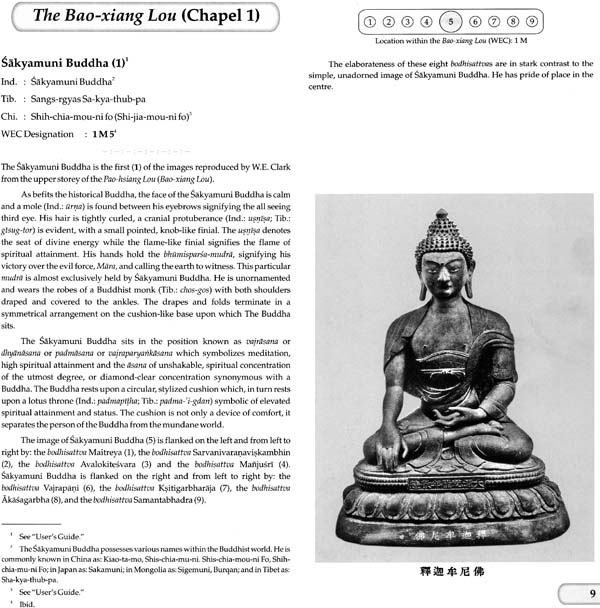

Technically, there is no difference between the two when either one or the other is utilized within a single pantheon. However, if within a given ensemble all but one were placed upon a single lotus throne and one image sat on a double lotus throne, this would give emphasis and elevate the importance of that figure. Let us say, for example, that in the middle ensemble of Chapel 1 (1 M 1-9) in which all the images are on a single lotus throne, but the central image in this case: Sakyamuni Buddha (1 M 5) was placed upon a double lotus throne this would obviously elevate the importance of this image. On the other hand, the fact that the numerous images within the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) pantheon, with obvious exceptions, all are placed upon single lotus thrones is but a choice of the artisan. Of only passing interest is the fact that these images, commissioned by the Emperor for his honoured mother were not placed upon a double lotus throne.

Of further interest is the rather elaborately banded plinth or extension that is to be seen protruding from the top of the single lotus throne employed for the Pao-hsiang Lou (Bao-xiang Lou) images (see Figure 7). This plinth or extension is cushion-like. Such an "extension" is also used, albeit in a different from. For the image depicted in the Chu Fo P'u-sa Sheng Hsiang Tsan (Zhu Fo Pu-sa Sheng Xiang Zan) pantheon. It may also be that this "elaborate" plinth is either a moon (Ind.: candra; Tib.: zla-ba) or a sun (Ind.: surya; Tib.:nyi-ma) disc that is often referred to as a device upon which a deity sits or stands. Indeed these symbols important to the Hindu are equally important to Vajrayana Buddhism. Virtually all temples and/or Vajrayana stupa (Tib.: mchod-rten) display a combined form as a finial (see Figure 8).

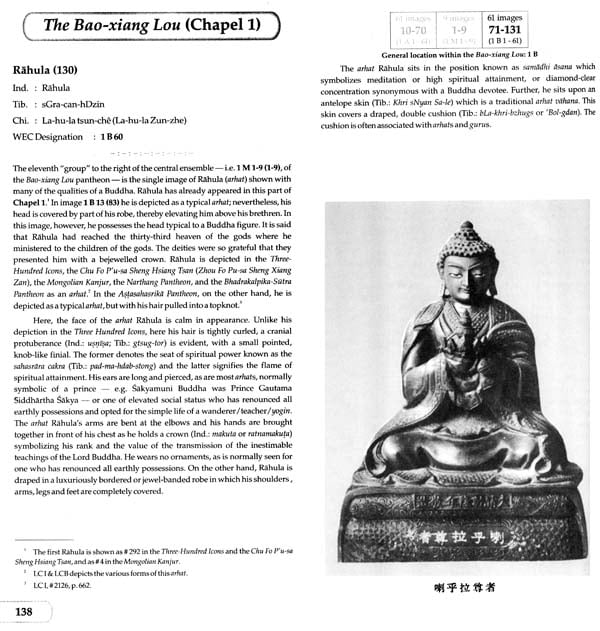

Finally, Milaraspa (1 A 35) is unusual as he sits upon a throne usually reserved for mahasiddhas. This throne consists of a double cushion over which hangs the skin of an antelope (see Figure 9 [simplified]). The erhat's throne is similar, but without the antelope skin i.e. simple double cushion as seen in 1 B 15.

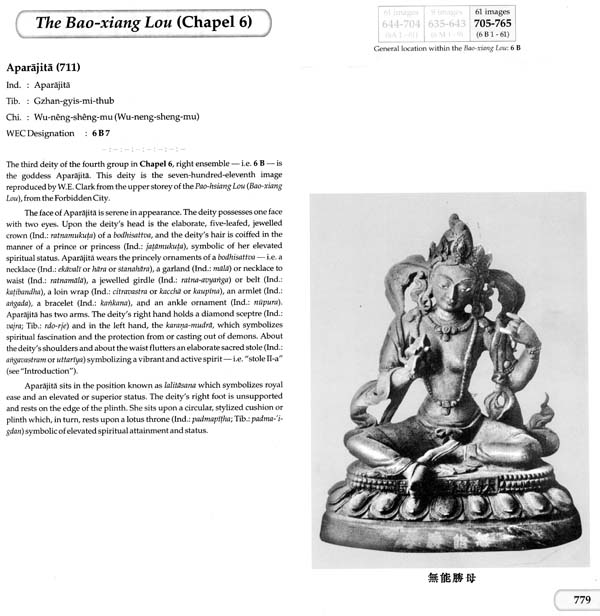

Variations Stole

Difference were first noted in the treatment of the sacred stole (Ind.: angavastram or uttarya). The difference was clearly noted in the images: Makara (Deva) (3 A 16), Sasthi Tithi (3 A 18), Suryaprabha Deva) (3 Z 26), Mina (Deva) (3 A 27), Kumbha (Deva) (3 A 19), Shih-I-wo-shih-ma-mu (3 A 20) and Qavalokitesvara (Bodhisattva (1 A 11). Here the first two deities' i.e. Makara (Deva) and Sasthi Tithi stole draped about their shoulders, fell to the base, and the tips "Fluttered" up somewhat (hereafter referred to as: stole I-a") (see Figure 10). There is a variation no "stole I-a" as seen in Suryaprabha (Deva) 3 A 26 and Mina (Deva) 3 A 27 among others. Here the ends of the stole do not turn upwards as seen in "stoleI-a," but hang over the edge of the base and lotus throne (hereafter refereed to as: "stole I-b) (see Figure 10). On the other hand, the second two deities' i.e. Kumbha (Deva) and Shih-I-wo-shih-ma-mu stole did not drape about their shoulders, but are arched or fluttered outward dramatically, forming two distinct forms or lobes that are completely different from the first two (hereafter referred to as: stole II-a") (see Figure 10). In Chapel 1 a variation is found on "stole II-a" i.e. Avalokitesvara (Boddhisttva). Here the stole flutters about the deity's shoulder, but the ends drape over the edge of the vahana (hereafter referred to as: "stole II-b") (see Figure 10). Examples of "stole II-a" are generally encountered in the images of fierce deities, while "stole I-a," "stole I-b" and "stole II-b" are almost never seen in conjunction with fierce deities.

Chapel 4 is an even more telling example. There, but for a couple of images, all are peaceful seated deities. The majority are shown with "stole I-a or b," the angavastram resting on their shoulders, to be precise, eighty-three images, while forty-two are depicted with high arching, agitated stole, "stole II." Further, when analysing the images of Chapel 1 M and comparing them with the first few similar attired deities of Chapel 1 A, another factor 4 and 1 M 6-9 all had similar "stole II" types. However, 1 A 1-4 had "stole II" types, but, they were far more pronounced, more dramatic. The 1 M images' stoles were more compact, whereas the "stole Ii" types of 1 A 1-4 flared out more dramatically and displayed pronounced lobes along the outer edge. 1 M 1-4 and 1 M 6-9 are, therefore, identified as "stole II-s" and 1 A 1-4 as "stole II-b" types (see Figure 11).

Variations Head

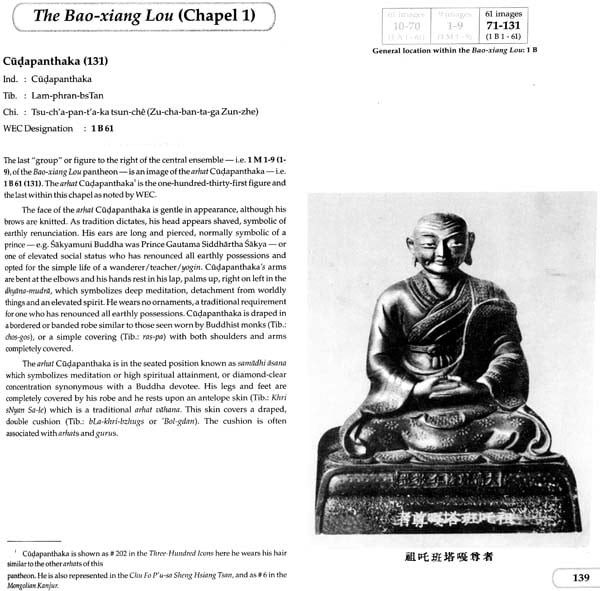

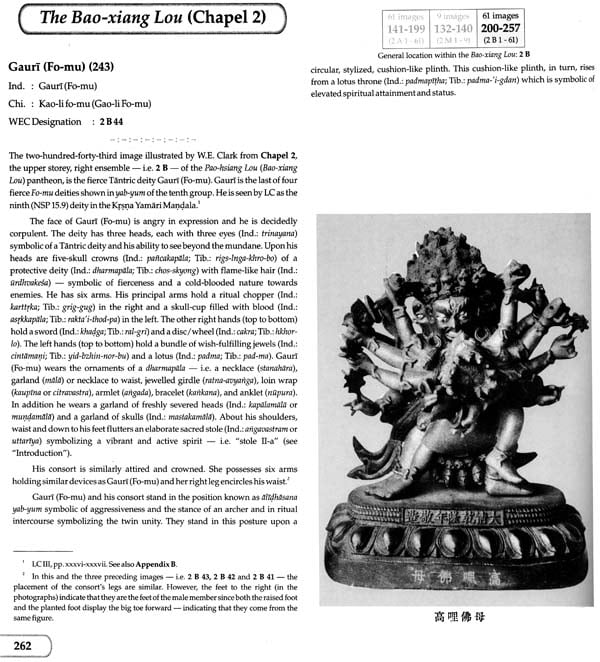

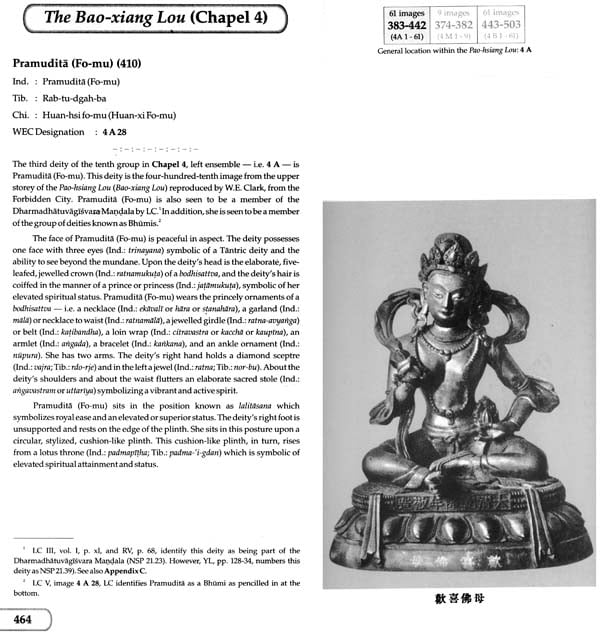

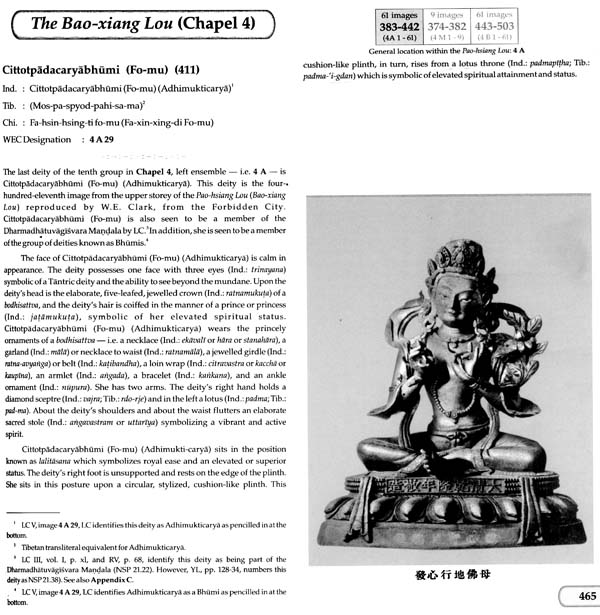

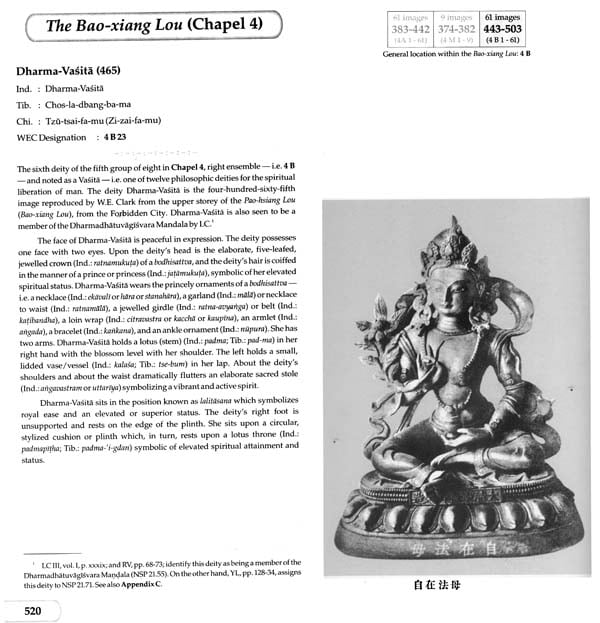

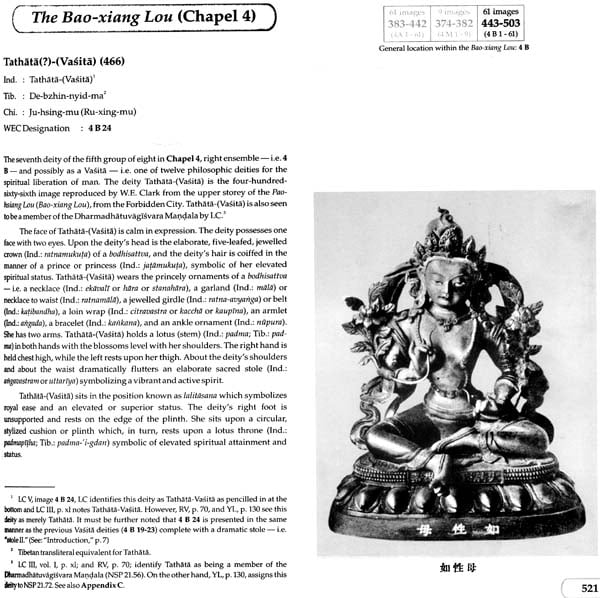

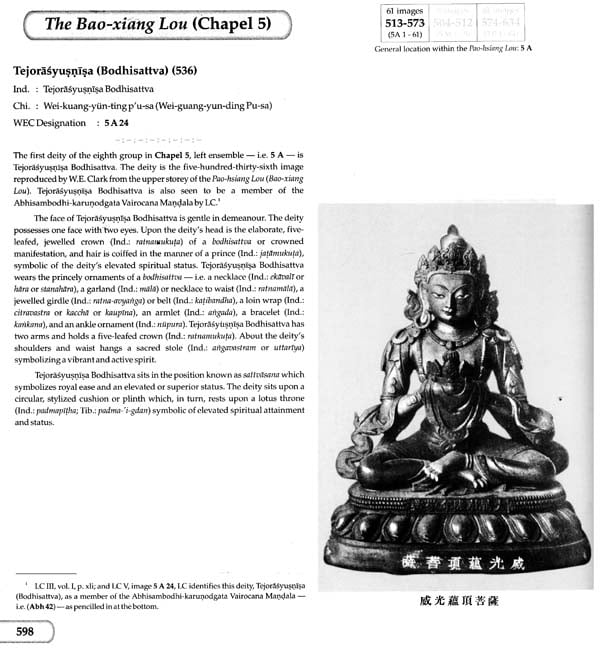

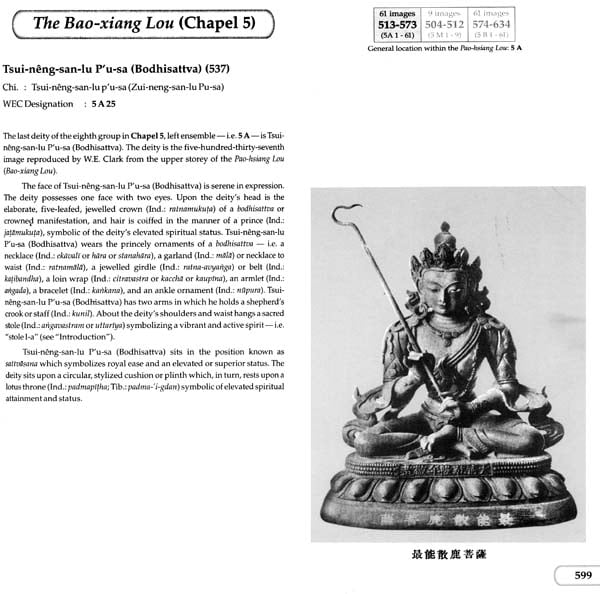

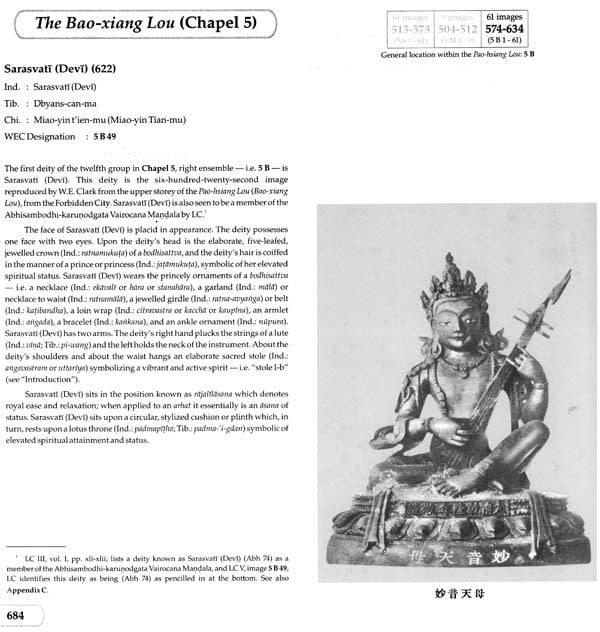

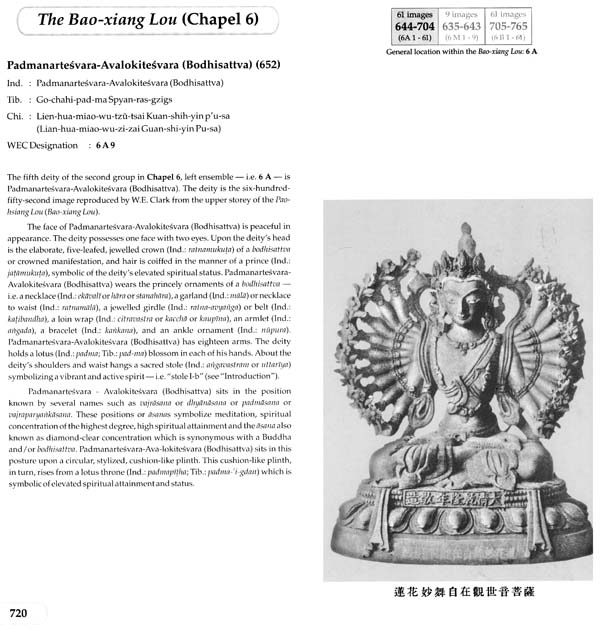

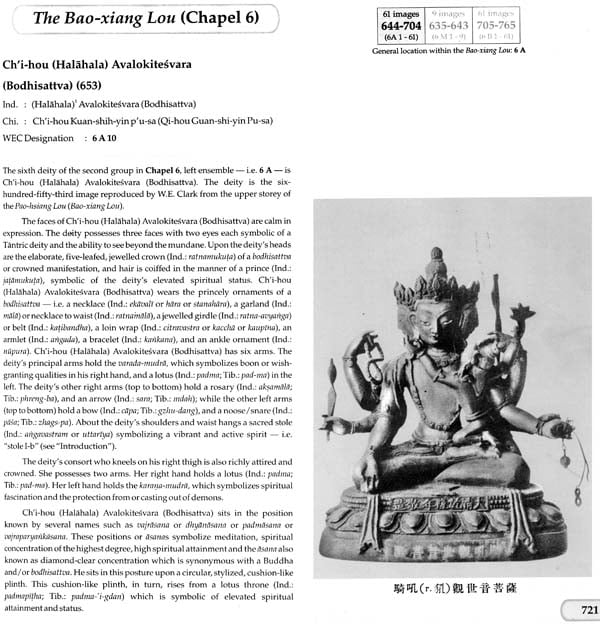

The proportions of the images, particularly the head and face, follows set standards, a canon. In Tibet this revolves around the depiction of the Lord Buddha and is often referred to as the characteristics of physical harmony and beauty (Ind.: laksana; Tib.: mTshan-bzang) (seen Figure 12). Although not strictly immutable, they are assiduously adhered to when depicting a sacred image. Within the Bao-xiang Lou images, slight variations are observed. This observation of differences is further underlined by the treatment of various features and details. In the following: Chapel 4 is used as an example (see Figure 16-19). First, there is a variation in the manner in which the hair is coiffed. The stylistic difference may be seen in the hair style between 4 M 1 as well as 4 A 22 and 4 A 4. The hair of 4 M 1 and 4 M 22 is narrower, tightly formed, while that of 4 A 4 is fuller, similar to the kumbha or jatamukuta style. This cannot be attributed solely to the status of the deity as both 4 A 4 and 4 A 22 are of the same rank i.e. Fo-mu. The tightly coiffed style is referred to as "hair A" (see Figure 13) while the fuller style is referred to as "hair B." Second, is the difference in the crowns of the deities. The crown of 3 M 5, the presiding deity, sets an archetype.