अद्वयवज्रसंग्रहः Advayavajrasamgraha

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAQ815 |

| Author: | Mahamahopadhyaya Haraprasad Shastri |

| Publisher: | Oriental Institute, Vadodara |

| Language: | Sanskrit Only |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| Pages: | 72 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.50 X 7.50 inch |

| Weight | 360 gm |

Book Description

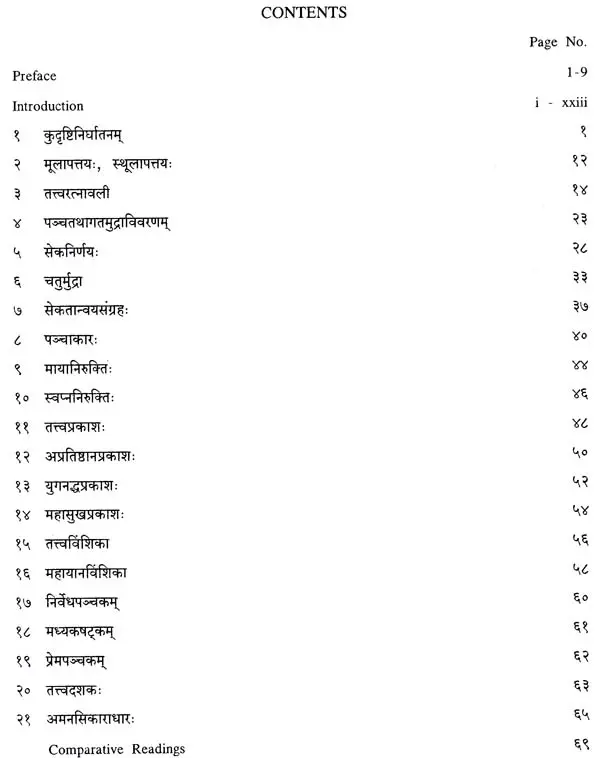

It gives me great pleasure to present to the world of scholars this reprinted book named Advayavajrasamgraha. It was edited by M M. Haraprasad Shastri and was first published as Gaekwad's Oriental Series Volume No. XL in 1927. It was out of stock and is still in great demand from the scholarly world. It is, therefore, reprinted with new computerized type-set. The work is a collection of twenty one small texts, composed by Advayavajra (C. 1100 A.D. or early 1200 A.D.), explaining important tenets of Buddhist Philosophy. The Oriental Institute has published many unique and important works of Buddhist Philosophy, during the earlier period, when Dr. B. Bhattacharya was General Editor of the Series. He himself was a veteran scholar of Buddhist Philosophy and edited also some of these works. Most of these works are now out of stock. The Tattvasangraha of Santarakṣita alongwith Commentary by Kamasila was reprinted in four volumes (two having Sanskrit text and two volumes containg the English translation). The work Sadhanamala Vol..I and II has been recently reprinted. I am sure that like all our previous publications, this book will also be warmly received by the scholarly world. I am thankful to the colleagues of the Institute for their co-operation in various ways for the reprinting of this book. I am also grateful the Shri P. N. Srivastava (OSD), Shri S. M. Pattni, I/c. Press Manager and his co- operative staff for quickly reprinting the book. I thank the University Authorities for releasing the necessary grant.

Bodhi-sattva Asvaghosa was the Guru of Kaniska, the Yueh-Chi Emperor, whose territories extended from the Vindhya to the Al-tai, and who flourished at the end of the first century A.D. and was perhaps the founder of the Saka Era which started from 78 A.D. Asvaghosa wrote a poem on the life of Buddha entitled the Buddha-Carita and another entitled Saundarananda embodying Buddha's teachings and giving the story of the conversion of his step-brother Nanda. At the end of this book Asvaghosa says that as physicians often prescribe bitter pills but for the benefit of the patients and have them sugar-coated, so he after writing many difficult and abstruse works on Buddhist philosophy wrote poems to make these abstruse ideas palatable. Asvaghosa wrote many philosophical works, one of which Mahayana-sraddhotpada-sutra though lost in Sanskrit is to be found in Chinese translation, and has been recently translated into English by a deeply read Japanese scholar named Dr. Sujuki. A perusal of that translation dispels the myth that Nagarjuna was the founder of the Mahayana system. It now appears that Asvaghosa was the first great writer of that system and that Nagarjuna preached it enthusiastically at a later time, but that it existed before these great men. Asvaghosa in his Buddha-Carita says that Buddha after his great renunciation went to two well-known scholars of the time for instruction, one Araḍa- kalama and the other Uddaka, son of Rama; both of them taught him the Sankhya system of Kapila with eight Prakrtis and sixteen Vikaras and Purusa. They taught him of the advance of the human soul from the lowest sentient beings through Kama dhatu, and Rupa-dhatu to Arupa-dhatu, that is, through the world of desires and world of forms to the world of no form, that is, of light.

Arada Kalama further taught that in the formless heaven there are two stages: Akasantyayatana the formless human soul as infinite as the sky, and Akincanyantyayatana or the formless human soul as infinite as consciousness. Uddaka Rama-putra taught him that there was another and a higher stage where the formless human soul is as infinite as Naiva-samjna-na-Samjna-nantayatana 'no holder of a name and no ame in infinity.' At the final stage the human soul so advancing becomes Kevali or absolute, without any relations, that is, beyond the world of relativity. Buddha was not satisfied. He said if the human soul exists it must exist in relation to something, it cannot be absolute, and so he left his Gurus and proceeded unaided, by study and meditation, to attain the highest position in bliss. He soon saw that the whole of the Sankhya is based on Sat-karya-vada, or the theory that the effects exist in a nascent form in the cause, that is, the cause and effect are both permanent and abiding. So Buddha discarded this theory of permanent effects and established what is known as Ksanaika vada, i.e., all things exist only for a moment and they are not permanent. The soul also was momentary and so the highest position is that there is no Samjna and no Samjni- no name and nothing to which a name may be attached. In this case there is no harm in the human soul (which is not permanent in his theory), being absolute without any relationship. Buddha thought the whole universe to be in a flux, both subjectively and objectively.

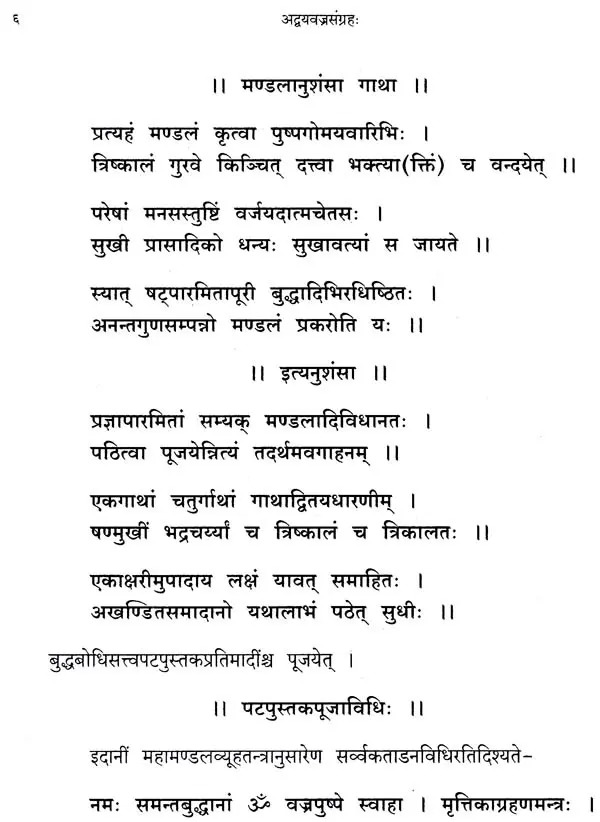

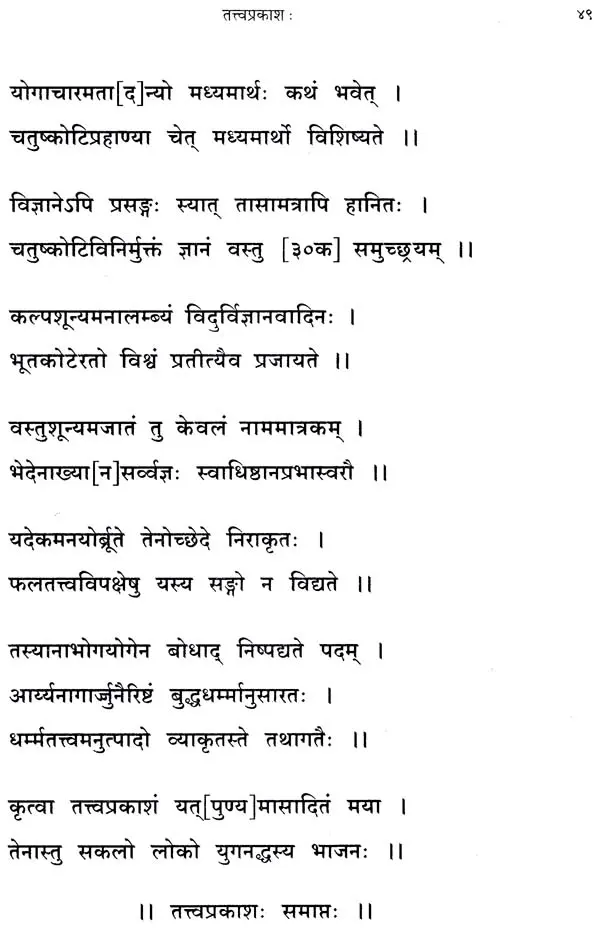

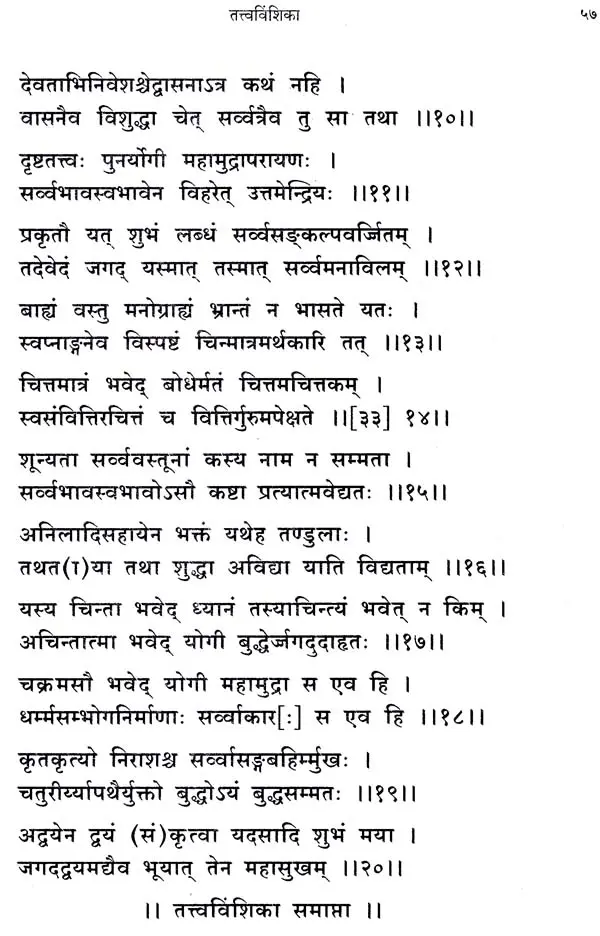

I went to Nepal for the purpose of examining MSS. in the Darbar Library in 1907 and I took notes of certain palm-leaf MSS. and paper MSS. in that Library. When editing these notes for the second volume of my Nepal Catalogue in 1915, I found that a MS. entered there as Tattva-dasaka was a collection of short works the last few leaves of which had that name. When I went again there in 1922, I examined the MS. carefully and found that it is a collection of 21 or 22 works mostly by Advayavajra on points relating to Buddhism almost chronologically arranged. The scope of the work ranged from the time of the rise of Mahayana to the time of Advayavajra in the eleventh or early twelfth century. The age of Advayavajra has been fixed by Dr. Benoytosh Bhattacharya in his Introduction to the Sadhanamala. So I need not dilate upon it. The 22 short works seemed to me to be very important for the history of Buddhism, because (1) they gave much information that was not found in the works on Buddhism written up to date from Indian, Tibetan, Chinese or other sources, (2) because they came from an Indian source, and (3) because they threw light on the period of Buddhism scarcely studied, namely, from the time when the Chinese ceased to come to almost the time of the fall of the Pala dynasty. I therefore took care to copy the MS.; I myself dictated the work to my son Kalitoṣa who wrote it from me. I compared his writing with the MS. several times and His Grace the Rajaguru Hemaraja had the two compared by his pupils who were students of Palaeography with me. Thus I thought the copy to be faithful and I was anxious to get it printed. His Highness the Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad lent me the hospitality of his now famous Series of Sanskrit publications and I presented the copy made by me to his Library of MSS.

But during the course of passing the MSS. through the press, I found that a collation with original MS. in the Darbar Library was absolutely necessary and I applied to His Highness the Maharaja Sir Chandra Samsher Jang Bahadur Rana to lend me the MS. for a short period and my request was most graciously granted. I have given a list of readings in which the copy differed from the MS. But still there are readings which are doubtful but I did not venture to make conjectural emendations as there were no Lamas with me to whom I might refer for collating with the Tibetan translation. I did not venture to give an English translation of the work for several reasons (1) because the readings are in many places so hopelessly corrupt that nothing can be made out of them; (2) the subjects are so unfamiliar that I can expect no help from any one in India; (3) the technical terms of Mantrayana and Vajrayana are still a mystery to Buddhist scholars; (4) the sentences are so elliptical that it is difficult to make a grammatical construction. Advayavajra himself says that he hated diffuseness and was a lover of brevity, and in making his works brief he has made them enigmatical, and brevity has often degenerated into obscurity. For all these reasons I have abstained from giving a translation. I give the work as it is and I hope my readers will look at me with indulgence, but I venture to think that the works will throw much light on obscure points of Buddhist History and Buddhism and that is an excuse for their publication.

**Contents and Sample Pages**