British Military Policy in India, 1900-1945 (Colonial Constraints and Declining Power)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAZ917 |

| Author: | Anirudh Deshpande |

| Publisher: | Manohar Publishers and Distributors |

| Language: | ENGLISH |

| Edition: | 2005 |

| ISBN: | 9788173045837 |

| Pages: | 224 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 350 gm |

Book Description

The decline of British imperialism had far-reaching colonial and post-colonial consequences. British policy and Indian history, for obvious reasons, unfolded in the foreground of this decline from 1900 onwards. This volume contextualizes crucial aspects of modern India's military past. It contends that British imperialism, like all empires, declined due to its inherent contradictions. Managing the military affairs of the British Raj comprised a crucial element of these contradictions.

While mentioning the challenges posed by India's military system to British policy this volume highlights the tension between the imperatives of reform and the compulsions of economy and traditions felt both by the British and Indians involved in managing colonial military affairs. Between 1900 and 1939 the colonial Indian war machine could be refurbished only up to a point primarily because of the very system which had produced it. The significance of military reform and decolonization was first underscored by the Great War (1914-18) and subsequently even more by the Second World War (1939-45).

This socio-political history of the colonial Indian military organization investigates why reform remained largely theoretical even as the British used Indian resources to defend a weakening empire through two World Wars. Ultimately World War II transformed the Indian armed forces but eventually, as this book asserts, this transformation worked against the British.

Anirudh Deshpande is a former UGC and ICHR Fellow, and is presently a Fellow at the Centre for Contemporary Studies, Nehru Memorial Museum & Library (NMML), researching visual history in modern India. He has co-edited with the late Professor Partha Sarathi Gupta The British Raj and its Indian Armed Forces, 1857-1939 (2002). He has published papers, commentaries, reviews, and articles regularly since 1987 in various journals and newspapers. In the year 2000, he wrote a scientific paper on opium production in India and its regulation by the colonial and post-colonial Indian state as a national consultant historian for the United Nations Drug Control Programme (UNDCP). His recent publications include an NMML Monograph The Stigma of Defeat: Indian Military History in Comparative Perspective and a paper titled `Interpretative Possibilities of Historical Fiction: A Perspective on Kiran Nagarkar's Cuckold', in Yasmeen Lukmani (ed.), The Shifting Worlds of Kiran Nagarkar's Fiction (2004).

This book examines the implications of British military policy in India in a period marked by declining British power. British military doctrine had evolved into a set of seemingly inflexible principles at the beginning of the twentieth century. Between the late eighteenth and the closing decades of the nineteenth century, Britain's naval mastery on the high seas inculcated a belief in British military invincibility in British imperial ruling circles. In the second half of the nineteenth-century weaknesses in Britain's military position surfaced and led to the policy of appeasement. Appeasement stayed with Britain till 1939 and was symptomatic of the undercurrents of the changing British military position between 1850 and 1950. British military policy was located in a context in which war became increasingly unprofitable.

Between the Crimean and the Great War technological developments transformed the meaning of strategy and sea power. Trains meant growing land power. The motorization and timely concentration of divisions rendered a seaborne invasion of the continent obsolete. Land power was demonstrated in the wars of German unification. Following this, in the twentieth century, airpower became equally, if not more, important. British responses to these developments were late. The Great War demonstrated the hiatus between Britain's strategic interests and her economic and ideological capacity to attain them. Above all, modern warfare meant that fleets had to develop in consonance with land and air power. This required the support of a vigorous, versatile, and innovative industry which the British colonial empire did not possess.

Between the two World Wars Britain's military planning was governed by the Ten Year Rule and the so-called 'peace hypothesis'. In the 1930s Britain fell back on treaties aimed at limiting the arms race and gaining time. But diplomacy is rarely a substitute for power. In these circumstances, the Indian armed forces felt the effects of British military policy. But British policy was not merely a product of official attempts to grapple with imperial decline. It was conditioned by the economic, social, and political factors peculiar to colonial India. Increasingly, and against their will, the British contended with Indian opinion in military matters. This was a prelude to their experiencing the consequences of changing Indian social realities during the Second World War.

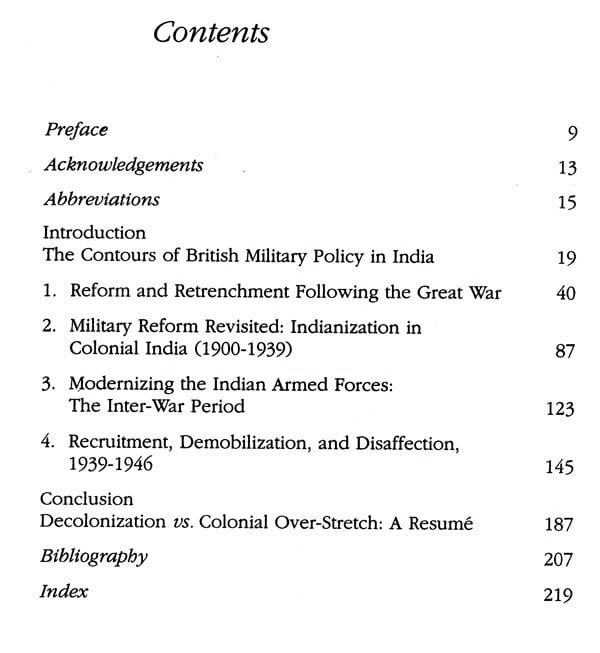

The British and Indian perspectives on military reform, the inter-War retrenchment, the issues of Indianization and modernization, the change in recruitment due to the demands of war, and finally the harsh realities of demobilization are the salient features of Indian military history studied in this hook. The first three chapters-preceded by a comprehensive introduction to British policy, strategy, and colonial over-stretch in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries-analyze the reform process, retrenchment, Indianization, and modernization affecting the Indian armed forces in detail. Chapter 4 examines military recruitment in India. It focuses on recruitment changes and their consequences during the Second World War. It also compares the process of demobilization after the Great War with what happened after the Second World War. The Conclusion criticizes `decolonization' and reiterates the central problem of imperial systems: all empires decline sooner or later because the costs of maintaining them ultimately exceed the material and mental resources they generate.

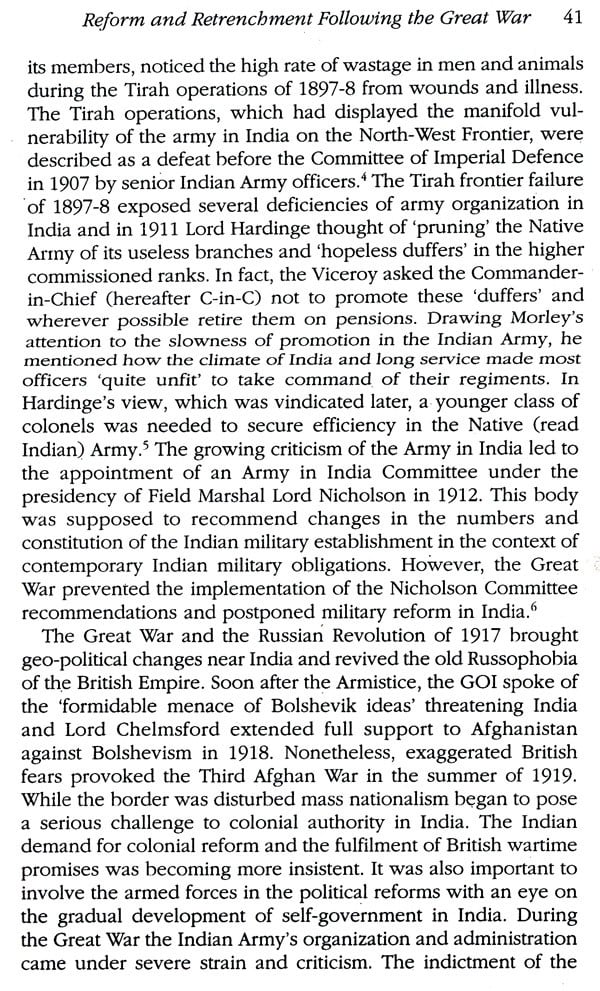

The modern Indian Army dates back to the nineteenth century. The three Presidency Armies of the eighteenth century changed during the course of the nineteenth century. The greatest transformation occurred in the Bengal Army. The Indian Army was later reorganized into nine divisional commands and its regiments were renumbered under the leadership of Lord Kitchener. Earlier the Mutiny proved to be a watershed event in Indian military history. It led to the exclusion of Indians from the artillery, the construction of cantonments to segregate the Army from the bazaar, and greater racial distance between the European and Indian components of the Army in India. From the 1880s onwards and till the Second World War the martial races theory governed the recruitment of Indians in general. This was done to keep the Indian Army manageable and loyal.

India assumed a new geopolitical significance for the British imperial interests between the two World Wars. The consolidation of the USSR in the 1920s and the growing Axis threat of the 1930s gave India new importance in British imperial strategy. However, this was rarely expressed in policy affecting the Indian services. In sum, even a certain appreciation of India's position in the Empire after the Great War did not bring about large increases or modernization in the Indian armed forces. The reforms contemplated after 1918 were predicated upon the experience of the Great War and the changing international position of the British Empire after it. But the economic limitations of the Raj put paid to them.

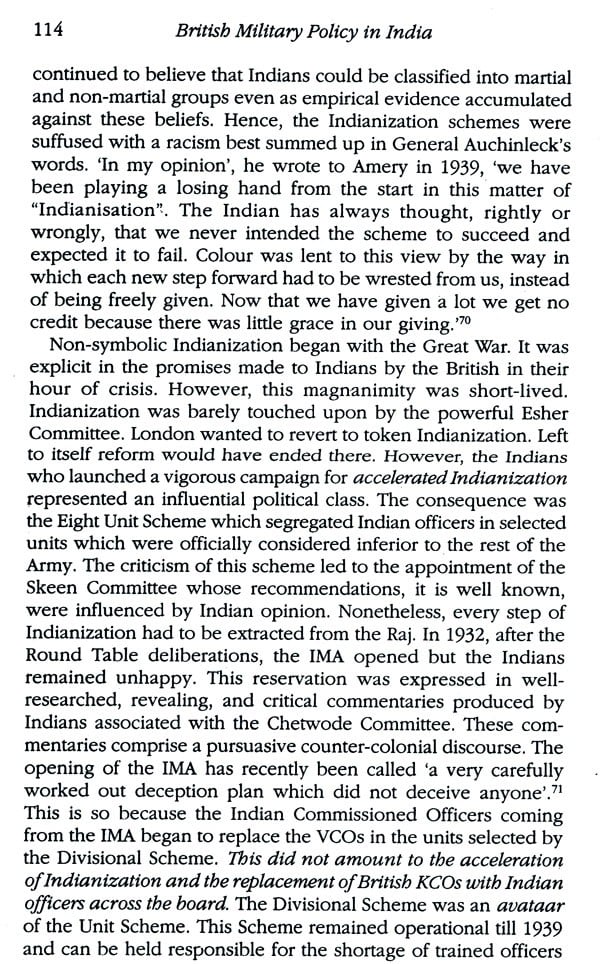

The Esher recommendations, with their limitations, were destined to be wasted in the 1920s. After all, the Victorian discourse which corsetted the Indian services contradicted the demands of modern warfare. The modernization of the colonial military establishment between 1900 and 1945 was also related to the social reform of the armed forces. At the heart of all this lay the matter of economies and Indianization. While the Esher recommendations bypassed practicable Indianization, the colonial state betrayed the wartime promises made to Indians. This led to an interesting contest of identities between the Indians and the colonial state on the Indianization question in the 1920s and 1930s. In the 1930s, besides Indianization, the military policy had to confront the problem of technological modernization. Here, once again, the economic legacy of the 1920s played a crucial role in deciding budgets and technological change. Consequently, when the policymakers tried to modernize the Indian services on the eve of the Second World War they ran into the chronic problems of the Raj in India. This is not to say that their perspectives, as late as 1938, were free of colonial prejudices inimical to Indian cooperation in the impending War. Following this, the Indian armed forces remained unprepared for a major war in 1939. In the event, the Second World War imposed fresh imperatives on the Indian military establishment while signaling the end of British colonialism in India. Our study of recruitment, demobilization, and discontent in this volume attempts a more nuanced understanding of this process.

**Contents and Sample Pages**