شاهی محمود -ی تاریخ: Tarikh-I-Mahmud Shahi- Persian Text (An Old And Rare Book)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAQ460 |

| Author: | S.C. Misra |

| Publisher: | The Mahraja Sayajirao University of Barodra |

| Language: | Persian |

| Edition: | 1988 |

| Pages: | 210 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 10.00 X 6.80 inch |

| Weight | 540 gm |

Book Description

The Tarikh's-Mahmad Shahr was edited by the late Professor S. C. Misra and the printing of its Persian text was completed in 1982. Professor Misra asked me to prepare its English index in August 1984, a few months after my joining him in the Department of History. He had planned to write an introduction to this work and, alongwith the index, the work was to have been finally released to the readers. It is sad that Professor Misra is no more when his work is coming out of the press. He died on 26 September, 1984.

I have appended a comprehensive index to the Persian text of the work as wished by Professor Misra. I have also written an introduction to complete the plan of publication of the volume.

I would like to record the help which Mr. A. A. Kazi rendered to Professor Misra in editing the Persian text and the Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi, for extending him financial assistance to undertake this project.

I would like to thank Professor V. K. Chavda, Head of the Department of History, M. S. University, Baroda, for extending me all possible help to enable me to fulfil my commitment to Professor Misra. I have also benefited from discussions with my colleague Dr. G. D. Sharma from time to time. Mr. Moosa Raza, L.A.S., kindly went through the type-script of the Introduction and gave me some valuable suggestions in organizing my material. I am extremely grateful to them. I am beholden to my father Mr.-S. Hasan Mahdi for taking pains in getting the title page caligraphed at Delhi. Lastly, my thanks are due to Shri P. N. Shrivastava, Manager of the M. S. University Press for printing the work.

Reader, Department of History M. S. University of Baroda

S. HASAN MAHMUD

Baroda

14 October 1985

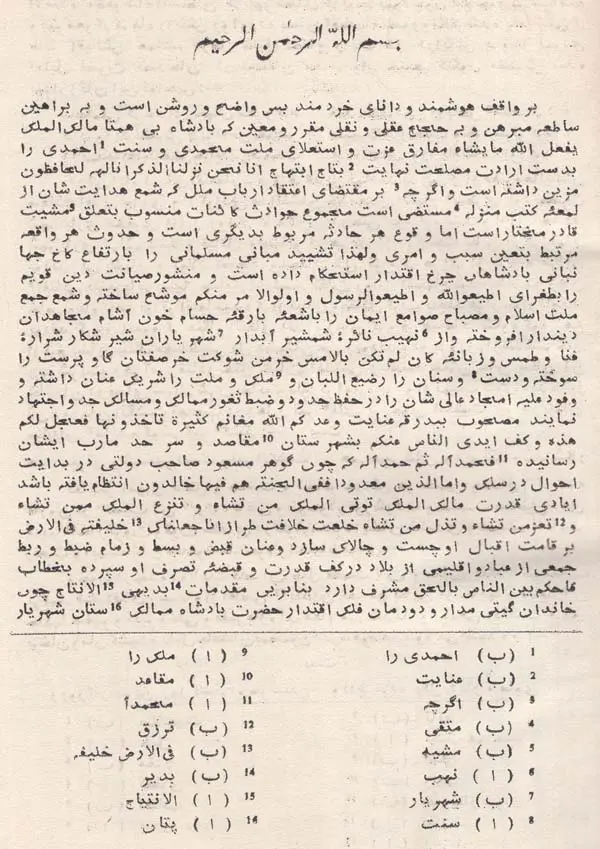

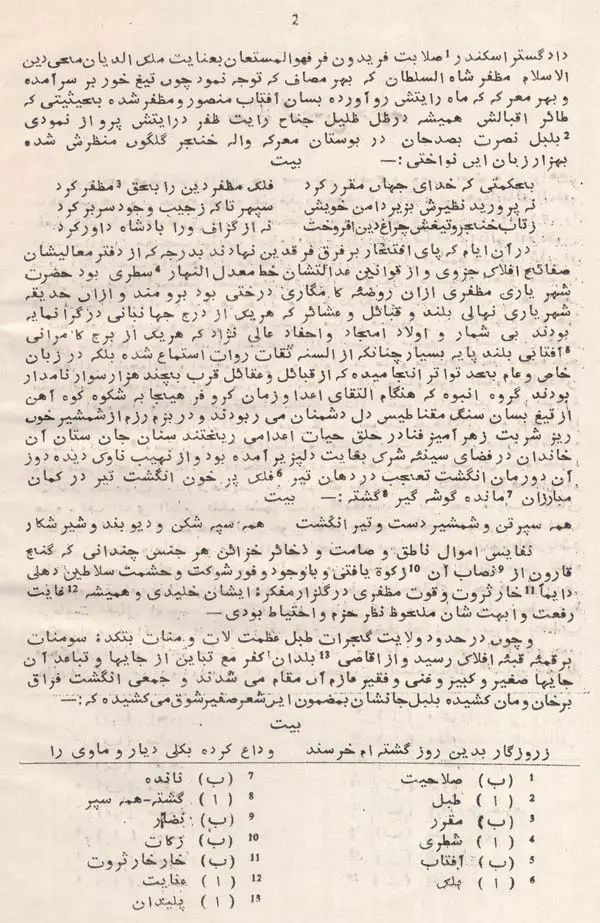

The Tarikhi-Mahmid Shahi belongs to the second half of the fifteenth century, written during the reign of Sultan Mahmad Shah, popularly known in Gujarat as Mahmud Begada, by far the greatest of the Sultans of Gujarat. It may, therefore, be appropriate to preface this introduction with a brief account of both the land and the age-the environment in which it was written.

The Land and the Milieu

Gujarat is the northern most region on the western sea board of India. Broadly, it is composed of three distinct sub-regions: the mainland, the peninsula of Saurashtra and the north-western region of Kacchh. Within Gujarat, these three regions have had a distinct identity, have developed advanced dialects and have a distinct history of their own.

The mainland is separated by an ill-defined belt which was once the extension of the sea-the gulf of Khambat. The northern plains formed the core of the earlier dynasties of the Sultanate. To the east was the piedmont region, relatively less accessible, which merged into the hilly regions both to the north and the east and south-east, which seperated Gujarat from Mewar, Malwa and the Deccan. The land was relatively arid upto Ahmedabad; between Ahmedabad and Bharuch it was better watered and thus formed the richest agrarian zone within the region. South of the river Narmada, where the hills closed in on the sea, and where it was cut by numerous rivers debouching into the sea, and the rainfall was high, the peneteration of the central authority of Gujarat was limited.

This region was watered by five major rivers, the Narmada, the Sabarmati, the Mahi, Vatrak and the Tapti. These rivers, however, were not of much use for irrigation, though in the north, they proved a deterent to the east-west traffic. They could be crossed only at a few fordable points and these strategic locations. on the Narmada in the south and the Mahi in the north, required particular attention of the central authority.

The rulers of the north Gujarat plains, the Chalukyas and following them the Sultans, were by all means, the most powerful not only within Gujarat, but also among the kingdoms in the neighbourhood. Nevertheless, it could not be possible for them to subjugate and assimilate into their system the local potentates and socio-political order. Both Saurashtra and Kacchh thus continued with their stays curbed, though it controlled by the Na The Sultans at best forced them to yield ground, created some focal points for their authority, but they could not sustain such an effort in the long run. The end result of all this was that it generated a perpetual tension.

The attempts of the Sultans to bring the zamindars of the mainland more firmly under their control met with only a limited success; it being confined to the more accessible regions They failed to have any success in this direction in the in accessible regions to the north, east and south-east, where the Rajpur kingdoms succeeded in maintaining themselves almost intact.

This syndrome of expansion and resistance explains much of the political history of the Sultanate of Gujarat. The relentless efforts of the Sultans to subjugate the local strongholds such as Champaner and Idar in the mainland and Jungadh in the peninsula have to be viewed in this context. This geo-political paradigm reflects, on a minor scale in Gujarat, the logic of much of the medieval Indian history.

A part of this internal logic was the compulsion, of what may be termed, in the context of the times, the external relations. Gujarat was by far the most powerful of the kingdoms that had sprung up in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, in the wake of the decline of the Sultanate of Delhi. Militarily, the Sultanate of Gujarat was far above those of Mewar, Marwar, Malwa, Khandesh and the Deccan. Yet it was not powerful enough to exterminate the internal base of these kingdoms and incorporate them into its own. Khandesh could be reduced to a sattelite status but an uneasy balance, always unstable and tension-ridden, existed so long as these kingdoms-Gujarat in the centre, Mewar and Marwar to its north. Malwa to its cast and the Bahmani kingdom, followed by its successor states, to its south continued to exist.

The failure of the Sultans to create a lasting local base for their power, referred to earlier, denied them the rich indigeneous base from which they could recruite their armed strength. Their nobility appears to be overwhelmigly composed of persons hailing from other parts of India-north India, the Deccan and elsewhere. Also, many of them were non-Indians: Afghans, Mughals, Arabs, Turks and so on. The bulk of the indigenous elements were the immigerant Muslims settled for long in Gujarat, like the Saiyids, and the convert Muslim groups mostly of Rajput origin. Only a few Hindu Rajput like Malik Gopi could penetrate into this priviledged order.