Tibetan Sacred Dance (A Journey into The Religious and Folk Traditions)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAO970 |

| Author: | Ellen Pearlman |

| Publisher: | Inner Traditions, Vermont |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2002 |

| ISBN: | 9780892819188 |

| Pages: | 200 (Throughout Color and B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 10.0 inch X 8.0 inch |

| Weight | 770 gm |

Book Description

Tibetan Sacred Dance explores the significance and symbolism of the sacred and ritual dances of Tibetan Buddhism. Since Buddhism entered the mythical land of the snows, Tibetans have expressed their spiritual devotion and celebrated their culture through dance. Only since the tragic diaspora of the Tibetan people have outsiders been privileged to witness these performances. To many, they still remain mysterious and enigmatic. Ellen Pearlman, who studied with Lobsang Samten, the ritual dance master of the Dalai Lama's Namgyal Monastery in India, set out to discover the meaning behind these mysterious dances. She found the story of the indigenous shamanistic Bon religion being superseded by and woven into Buddhism—a story full of complex liaisons, secret teachings, brilliant visions, and unrevealed yogic practices.

Pearlman explores the mystical beginnings and complex practices of sacred Cham—the secret ritual dances of Tibet's Buddhist monks—and Achi Lhamo, the storytelling folk dances and operas. She describes the mental and physical process of preparing for these dances, the meaning of the iconography of the costumes and masks, the spectrum of accompanying music, and the actual dance steps as recorded in a book of choreography dating back to the Fifth Dalai Lama in 1647. Beautiful color photographs from the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts and Pearlman's own images of touring monastic troupes complement the rare historic black-and-white photos from the collections of Sir Charles Bell, chief of the British Mission in Tibet during the life of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. From the week-long sacred Kalachakra initiation to the folk opera performances, Pearlman reveals the beauty, drama, and compelling nature of these dances and rituals and shows how Tibetan dance is an essential part of the rich history of Tibet and the survival of that culture.

ELLEN PEARLMAN has been a Buddhist practitioner for thirty years under Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and has studied with Buddhist teachers in the Far East and the Americas. She traveled to England, Germany, India, and Russia in preparation for this book. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

When I first journeyed to Dharamsala, India, home of the Dalai Lama in exile, I had been practicing Buddhism for only a few years. Following the traditional first step on the path—taking refuge in the Buddha, dharma (teachings), and sangha (community of practitioners)—I went and took refuge under a Tibetan lama, Kalu Rinpoche, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1974.

Inspired to get closer to the source of Tibetan Buddhism, in 1977 I traveled to Dharamsala, where the exotic Tibetan culture-in-exile transplanted to India both baffled and magnetized me. I had no idea just how lucky I was to meander unimpeded around Namgyal Monastery, the monastic compound of His Holiness, the Dalai Lama watching in awe as monks in rough crimson robes—studying for their degree of Geshe, or Ph.D. in philosophy—smacked their malas (rosaries) together as they made a particularly invigorating point in their logic debates.

One overcast and soft gray afternoon I noticed Tibetans hanging around the complex speaking excitedly. Out of the corner of my eye I saw a group of dancers whoosh by in colorful and ornamented brocade costumes. Fortunately, I happened to be carrying a crude box camera and instinctively reached for it, clicking as they rushed by on their way to perform a sacred ceremony. Intrigued, I followed. Although I wasn't allowed to enter the shrine room, I was able to watch through the open door.

Monks pursed their lips and blew through enormous long horns, followed by blasts from other monks playing shorter trumpets. The hair on my arms stood on end and I felt something no music had ever stirred in me before, a sense of coming back into myself. Dancing slowly and deliberately, in measured synchronized steps, the dancers turned while the cymbals clashed and a bass drum beat out a slow, continuous rhythm.

I don't remember how long this went on but I do remember that my mind, literally, stopped. All concepts drained away and I could focus only on the spectacle in front of me. I didn't know then that I was experiencing bod-hicitta, a basic unobscured state of clarity and emptiness. I didn't understand what I was seeing, nor did I know what it meant. I was clueless about what the monks were practicing—a special kind of meditation that used body, speech, and mind. I just knew I felt at peace, and returned to an inner tranquility I knew was there but didn't know how to find.

The profound impact of my first encounter with Tibetan sacred dance led me to undertake a long search to understand what I had seen and experienced. That journey led me deep into Tibetan culture, history, and spiritual practices, and into the story of one religion, Buddhism, taking precedence over another, the ancient, shamanistic Bon religion that existed when Buddhism was first introduced into Tibet. I've had wonderful teachers, friends, and guides along the way to explain the legends and symbols, the meanings and functions, of both kinds of Tibetan dance—the Cham, or "lama," dance performed by monks and Achi Lhamo, or folk dance. I learned that Cham (Tibetan for "a dance") serves a ritualized, sacred purpose, while Achi Lhamo (Tibetan for "sister goddess") is performed for entertainment, to retell historical legends, and for general merriment.

I invite you to share my journey through the wonders and mysteries of Tibetan dance in the pages that follow.

Contents

| Prologue | 1 | |

| 1 | Cham: Sacred Monastic Dance | 7 |

| Entering the World of Cham | 13 | |

| Vajrakilaya, the Dance of the Three-Sided Ritual Dagger | 17 | |

| Cham and the Development of Tibetan Religion | 28 | |

| Representative Chams | 35 | |

| Skeleton Dance | 35 | |

| Deer Dance | 38 | |

| Black Hat Dance | 41 | |

| Old White Man from Mongolia | 44 | |

| Mongolian and Other Chams | 46 | |

| Kalachakra, the Wheel of Time | 48 | |

| Cham Gar | 54 | |

| Essential Elements of Cham | 55 | |

| Preparation and Initiation | 55 | |

| Three Main Phases of Cham Performance | 67 | |

| Mandala and Mantra | 60 | |

| Dance Steps and Mudras | 63 | |

| Costumes | 69 | |

| Masks | 74 | |

| Characters | 77 | |

| Music | 84 | |

| Musical Instruments | 90 | |

| Festivals | 97 | |

| Purpose and Interpretation | 100 | |

| 2 | Achi Lhamo: Folk Dance and Operatic Traditions | 109 |

| Origins and Development of Achi Lhamo | 114 | |

| Early Origins | 114 | |

| Thangtong Gyalpo | 115 | |

| Development of Achi Lhamo | 119 | |

| Major Operas | 161 | |

| Drowa Sangmo | 123 | |

| Gyalsa Bhelsa | 125 | |

| King Gesar of Ling | 126 | |

| Pema Woebar | 131 | |

| Rechung U Pheb (Rechungs Travels to Central Tibet with Milarepa) | 135 | |

| Sukyi Nyima | 136 | |

| Thepa Tenpa | 139 | |

| Chungpo Dhonyoe Dhondup | 140 | |

| Nangsa Woebum (Obum) | 140 | |

| Essential Elements of Achi Lhamo | 143 | |

| Phases of Achi Lhamo Performance | 143 | |

| Types of Performers | 148 | |

| Singing | 149 | |

| Music and Instruments | 154 | |

| Folk Dance Styles | 158 | |

| Lhamo Gar | 163 | |

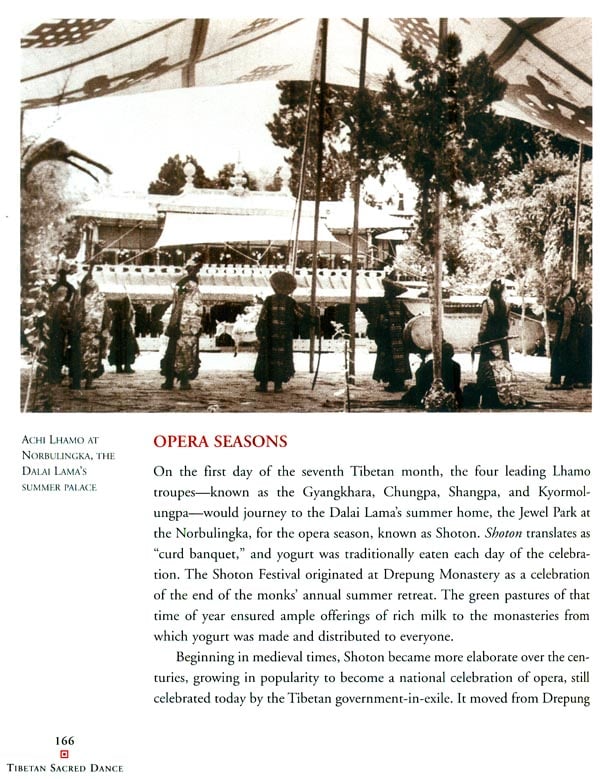

| Opera Seasons | 166 | |

| Epilogue | 173 | |

| The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts | 174 | |

| New Forms | 178 | |

| Cham Today | 180 | |

| Notes | 183 | |

| Bibliography | 189 | |

| Index | 190 |