Brhat-Samhita of Varaha-Mihira(Set of Two Volumes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAE028 |

| Author: | N. Chidambaram lyer |

| Publisher: | Parimal Publication Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | (An Exhaustive Preface Sanskrit Text English Translation Important Notes & Index of Verse) |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9788171104215 |

| Pages: | 801 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 1.30 kg |

Book Description

Varahamihira is considered to be the foremost Hindu Astronomer and Astrologer. He was master of all the three sections of Astrology. The outstanding works of Varahamihira are— 1. Brhat Saffihita. 2. Brhad Jataka, 3. Laghu Jataka. 4. Brhad Yogayatra, 5. SamAsa Sathhita etc.

Brhat Sathhita is the most celebrated work of Varahamihira. The 106 chapters of the Brhat Sarhhita contain all the practical and useful knowledge of the astronomical aspects for the daily life of the people in general. The chapters of this book contain in depth information about Astronomy, Geography, Meteorology, Portents, Agriculture, Economics, Physiognomy, Botany, Zoology, Erotics, Gemology, Augurus. Calendar, Stellar lore etc.

The present edition of Brhat Saitihita is a compilation of two texts out of which one is in Sanskrit language edited by Prof. Hendrick Kern - a well-known German scholar and the other is the English translation of the Brhat Sathhita by N. Chidambaram Iyer again a well- known South-Indian scholar. Both the texts have been edited thoroughly by the present editor Dr. Shri Krishna ‘Jugnu’ and the outcome is the present edition of Brhat Samfihita which is the first and the most unique of its type. This edition not only includes complete Sanskrit Text and English Translation, but also important Notes at various places and an Index of Verses at the last.

The name of Varaha-mihira must be familiar to every Saiskrit scholar from the writings of Colebrooke, Davis, Sir William Jones, Weber. Lassen. and, not least, from the writings of Albiruni, brought to public notice by Reinaud. But, however well known the name of the Hindu astronomer and astrologer may be, his works are disproportionally less generally known, because with one exception they existed only in Manuscripts and were consequently accessible to comparatively few. It is with the desire of propounding that knowledge that I have undertaken the editing of the most celebrated of Varaha-mihira’s works, the Brhat-samhita

Varaha mihira was a native of Avanti and the son and pupil of Adityadasa likewise an astronomer. The statement of Utpala that he was Magadha Brahmin must most likely be understood in this sense that his family derived its origin from Magadha

No information is to be found in the works of our author about the year of his birth nor could we expect to find it but in his astronomical treatise Pancasiddantika which unhappily seems to be wrong beyond hope of recovery. There is every reason to believe that we should find the author’s date in that because it is the all but universal practice of the Scientific Hindu astronomers to give their own date. In one way or the other, the Hindu astronomers at Ujjayani must have had means to know the date of Varaha-mihira, for in a list furnished by them to Dr. Hunter and published by Colebrooke,1 the date assigned to him is the year 427 of the Saka-era, corresponding to 505 AD.

It is not clear that to what period of his life this date refers. The trustworthiness of the Ujjayani list is not only exemplified by the fact that others of its dates admit of verification, but also in a striking manner by the information we get from Albiruni. This Arabian astronomer gives precisely the same date1 as Dr. Hunter’s list eight centuries afterwards, from which it is evident that the records of the Hindu astronomers have remained unchanged during the lapse of more centuries than there had elapsed from Varaha-mihira to Albiruni. The latter adds, what is not stated distinctly in the (Ujjayani list, that 505 AD. refers to the author’s Paflcasidd hantika. This statement would, on ground of analogy, seem to be corroborated by Dr. Hunter’s list, for two other dates at least, those of Bhatra-Utpala and Bhaskara-acarya admit of being verified, and as they refer to some works of these authors, not to the year of their birth, it is but natural to suppose that the same holds good in reference to Varaha-mihira. There are, however, two facts that make the date assigned to the Pancasiddhantika not indeed incredible, but improbable. The first is the date of Varaha-mihira’s death, as ascertained by Dr. Bhau Daji, viz. 587 AD. The second difficulty is the fact that Varah-mihira quotes Aryabhaqa in a work which cannot have been any other but Pañcasiddhantika.3 Nox; as Aryabhaga was born in 476 AD., it is unlikely that 29 years after, in 505 A.D., a work of his would have become so celebrated as to induce Varaha-mihira to quote it as an authority. It is of course not impossible, but not probable, while on the other hand the error of AlbirunT in taking 505 A.D. for the date of the Pancasiddhantika while it really was the date of the author’s birth may be readly explained. The inferences from astronomical data although proving indisputably that Varamihira cannot have lived many years before 500 A.D. are not numerous enough nor precise enough to eliminate from one or two data the errors of observation and sometimes necessary to make suppositions in order to arrive at any conclusion at all for a discussion of these I refer the reader to colebrooke’s Algebra.

Although not able to fix the date of Varaha-mihira’s birth with precision we know with certainty that the most flourishing period of his life falls in the first half of the 6th century of our era. This point important in itself has the additional value that it serves to determine the age of other Hindu celebrities whom tradition represents as his contemporaties. The trustworthiness of the tradition will form a matter for discussion afterwards; let us assume at the outset that the tradition is right, then it will follow that his contemporaries were Vikramaditya, the poets and literati at the court of this king, especially Kalidasa and Amara Sinha, and it may be added from another source, the author of the Pancatantra. We shall begin with Vikramaditya, and since there are more princes than one who bore that name, or title, we shall have to enquire, which of them may have a claim to be considered the contemporary of Varhamihira.

It is generally assumed that the first Vikramaditya known in the history of India, was a king reigning in the century before the Christian era, and that he was the founder of the Indian era, generally denoted by Samvat. The objections that may be raised against this opinion are so many and formidable, that no critical man can adopt the fact without submitting the varying testimonies of Hindu authors to a severe scrutiny. This has been done by Prof. Lassen, more fully, so far as I know, than by any other. But not withstanding the care bestowed by that distinguished scholar on the subject,his conclusions seem to me utterly inadmissible; it is therefore my duty to state the reasons why I cannot adopt the received opinion.

Lassen, well aware that weighty testimonies place Vikramaditya, the conqueror of the akas or Scythians, after not before, our era, and that same testimonies make him the founder of the aka era, not of the Sainvar, examines more than once their worth. In a foot-note to p. 50, of Vol. II. Of his Indische Alterthumskunde,” he says

“The astronomer Varaha-mihira calls this era the time of the kings of the akas; see Colebrooke’s Misc. Ess. II. p. 475.” The commentator explains The time when the aka kings were conquered by Vikramaditya.” A later astronomer, Brahma gupta makes, in reference to this epoch, use of the expression “the end of the aka kings,” which passage is explained by a commentator of Bhaskara, a still more modern astronomer, in this way the end of the life or of the reign of Vikramaditya, the destroyer of the Mleccha tribe, called aka.” The commentator of Varahamihira, consequently, as Colebrooke remarks, considers the era used by him to be that of VikramAditya, which every where else (sic.) is called Samvat. Brahmagupta reckons from salivahana’s era, so that the commentator here also wrongly brings forward Vikramaditya. I cite this because it shows that in after times they confounded the two kings and their history. Of the two astronomers the former lived in the beginning of the century, the latter in the beginning of the 7th the name of the aka era clearly explains its origin, and in this sense the expression of Varahamihira will have to be taken.”

So far Lassen. The objections to the foregoing are many and obvious; leaving out less important points, my first remark refers to Colebrooke’s startling conclusion, that Utpala (for he is the commentator in view) uses the Samvat era because he, Utpala, considers Vikramaditya sakari to be contemporaneous with the beginning of the saka era. What kind of weight has to be attached to such a conclusion, will be clear from an example nearer home. Let us suppose that some European considers, however erroneously, that the beginning of the Emperor Augustus’ reign and the beginning of the Christian era are contemporaneous facts; would then the only possible conclusion be this, that the man thinks that he lives in the year of grace 1896, instead of 1865? It is imaginable, certainly, that one might make such a mistake, imaginable, although it would be an abuse of language to call it possible. But let it be possible, it is not the only possibility; the man may have forgotten the precise date of Augustus’ reign, a much more probable contingency. Thirdly, it is again, imaginable, that the man places the two not conemporaneous facts, wrongly supposed contemporaneous by him, in a time which is wrong for both, say at the time of Pericles. The first and third conclusions are, to use a mild term, so extremely improbable that only the second is left. Let us apply it to the case of Utpala; and we shall find that the only, not preposterous conclusion in that Utpala places vikramaditya 78 A.D. not 57 B.C. What is a priori the only admissible conclusion become a posteriori quite certain because happily Utpala gives us his own date and in so doing affords us the means of ascertaining what he means by the Saka era. At the end of his commentary on Varahamihira’s Brhat-jataka we read.

| Preface | ||

| Chapter 1 | Introductory | 1 |

| Chapter 2 | The jyotisa | 4 |

| Chapter 3 | The sun | 17 |

| Chapter 4 | The moon | 25 |

| Chapter 5 | Rahu | 32 |

| Chapter 6 | Mars | 57 |

| Chapter 7 | Mercury | 61 |

| Chapter 8 | Jupiter | 66 |

| Chapter 9 | Venus | 81 |

| Chapter 10 | Sturn | 91 |

| Chapter 11 | Comets and the like | 96 |

| Chapter 12 | Canopus | 110 |

| Chapter 13 | The constellation of Saptarsis | 117 |

| Chapter 14 | Kurma vibhaga | 120 |

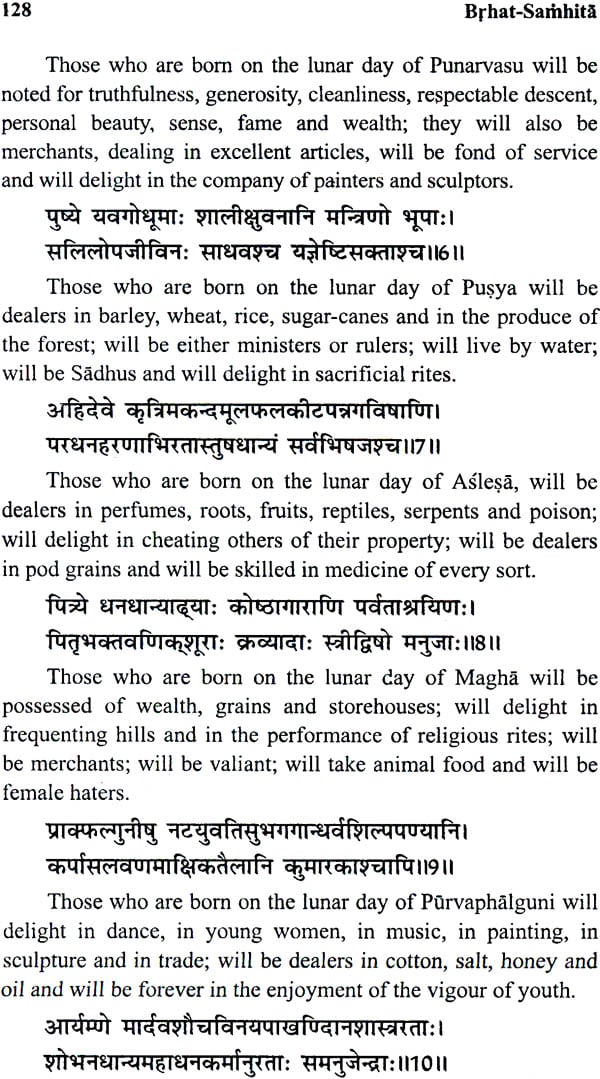

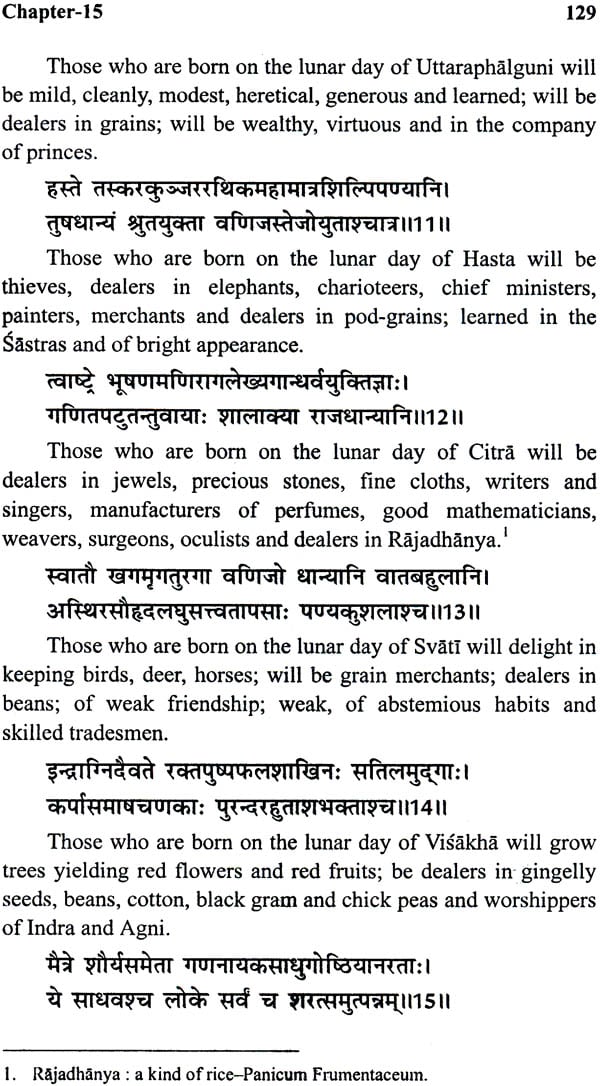

| Chapter 15 | The naksatras | 127 |

| Chapter 16 | The planets | 134 |

| Chapter 17 | Planetary conjunctions | 142 |

| Chapter 18 | Moon's Conjunction with the Planets | 149 |

| Chapter 19 | Planetary years | 151 |

| Chapter 20 | Planetary meetings | 158 |

| Chapter 21 | The rain clouds | 161 |

| Chapter 22 | Dharana or rain support days | 170 |

| Chapter 23 | Rain | 172 |

| Chapter 24 | Rohini yoga | 175 |

| Chapter 25 | Svati yoga | 184 |

| Chapter 26 | Asadhi yoga | 186 |

| Chapter 27 | The winds | 190 |

| Chapter 28 | Immediate rain | 193 |

| Chapter 29 | Flowers and plants | 199 |

| Chapter 30 | Twilight hours | 205 |

| Chapter 31 | Digdaha | 213 |

| Chapter 32 | Earthquakes | 215 |

| Chapter 33 | Ulkas or meteors | 222 |

| Chapter 34 | Halos | 228 |

| Chapter 35 | The rainbow | 233 |

| Chapter 36 | Singh of Aerial city | 235 |

| Chapter 37 | Mock suns | 237 |

| Chapter 38 | Dust storms | 238 |

| Chapter 39 | Thunderolts | 240 |

| Chapter 40 | Sasya jataka or Vegetable horoscopy | 242 |

| Chapter 41 | Commodities | 245 |

| Chapter 42 | The price of commodities | 248 |

| Chapter 43 | Indra dhvaja or indra's banner | 251 |

| Chapter 44 | Lustration ceremony | 265 |

| Chapter 45 | The wagtail | 271 |

| Chapter 46 | Portents | 275 |

| Chapter 47 | Motley miscellany | 295 |

| Chapter 48 | Royal bath | 1 |

| Chapter 49 | On Patta or crown plate | 17 |

| Chapter 50 | The sword | 19 |

| Chapter 51 | Angavidya | 25 |

| Chapter 52 | Pimples | 35 |

| Chapter 53 | House building | 38 |

| Chapter 54 | Under currents | 64 |

| Chapter 55 | Gardening | 88 |

| Chapter 56 | The building of Temples | 102 |

| Chapter 57 | Durable cement | 108 |

| Chapter 58 | Temple idols | 110 |

| Chapter 59 | Entry into the forest | 121 |

| Chapter 60 | The installation of the images in temples | 124 |

| Chapter 61 | The features of cows and oxen | 129 |

| Chapter 62 | The features fo the dog | 133 |

| Chapter 63 | The features of the cock | 134 |

| Chapter 64 | The features of the turtle | 135 |

| Chapter 65 | The features of the goat | 136 |

| Chapter 66 | The features of the horse | 139 |

| Chapter 67 | The features of the elephant | 141 |

| Chapter 68 | The features of men | 144 |

| Chapter 69 | Sighns of the five great men | 168 |

| Chapter 70 | The feauturs of women | 177 |

| Chapter 71 | Injuries to garments | 183 |

| Chapter 72 | Camara | 186 |

| Chapter 73 | Umbtellas | 188 |

| Chapter 74 | The Praise of women | 190 |

| Chapter 75 | Amianility | 195 |

| Chapter 76 | Spermatic drugs and medicines | 198 |

| Chapter 77 | Perfume mixtures | 204 |

| Chapter 78 | Sexual union | 219 |

| Chapter 79 | Cots and seats | 226 |

| Chapter 80 | Gems | 233 |

| Chapter 81 | Pearls | 237 |

| Chapter 82 | Rubles | 244 |

| Chapter 83 | Emeralds | 247 |

| Chapter 84 | Lamps | 248 |

| Chapter 85 | Tooth brush | 249 |

| Chapter 86 | Omens exhaustively treated | 252 |

| Chapter 87 | The circle off horizon | 269 |

| chapter 88 | Ominous cries | 279 |

| Chapter 89 | Omens connected with wild animals | 289 |

| Chapter 90 | The Cry of the jackal | 295 |

| Chapter 91 | Omens connected with wild animals | 298 |

| Chapter 92 | Omens connected with the cow | 299 |

| Chapter 93 | Omens connected with the horse | 300 |

| Chapter 94 | Omens connected with the elephant | 304 |

| Chapter 95 | The cawing of the crow | 307 |

| Chapter 96 | Supplementary to omens | 320 |

| Chapter 97 | Effective periods | 325 |

| Chapter 98 | The constellations | 329 |

| Chapter 99 | Lunar days and half lunar days | 334 |

| chapter 100 | Marriage lagnas and nakstras | 337 |

| Chapter 101 | The Naksatras | 338 |

| Chapter 102 | The division of the zodiac | 342 |

| Chapter 103 | Marriages | 344 |

| Chapter 104 | The efffects of planetary motions | 349 |

| Chapter 105 | The worship of the nakstras purusa | 367 |

| Chapter 106 | Conclusion | 371 |

| Index of verses | 373 |