Buddhist Paintings of Tun-Huang

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAJ978 |

| Author: | Lokesh Chandra |

| Publisher: | Niyogi Books |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9788192091235 |

| Pages: | 280 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 12.5 inch x 9.5 inch |

| Weight | 1.90 kg |

Book Description

About the Book

The Tun-huang caves are the sparkle of Buddhist art over the centuries, situated at the foot of the Mountain of Singing Sands, they are the brush of the Buddha, where an itinerant monk Yueh-ts’un watched the iridescent peaks in the sheen of blue satin, settled down to excavate the first cave in AD344, and to paint its walls with colours brought by birds as the folk legends has it. Speechless with joy, he had began a long journey of a thousand years of Buddhist meditation in the dazzling ecstasies of murals, scrolls and sculptures. This book reproduces and describes for the first time the paintings from Tun-huang in the National Museum, New Delhi. The 143 best scrolls have been narrated whose colours are still radiant images of the divine. The National Museum is one of the three major repositories of the Tun-huang paintings, the others being the British Museum London and the Musee Guimet, Paris. While the two latter collections have been published, this book fulfils a long-felt need and will cover a major lacuna of research in presenting the third large repository. The introduction traces the history of Tun-huang from the dreams of Chinese emperors to control the Deep Sands, the role of Yueh-chihs, the excavation of the first cave, the folk legends, the iconography of the murals from AD397-1368, etc. The Scrolls from Tun-huang are the charm of these caverns that once drew humans to their depths.

About the Author

Lokesh Chandra is an internationally renowned scholar of Tibetan, Mongolian and Sino-Japanese Buddhism. A prolific writer, he has to his credit 600 works, including critical editions of classical text in Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mangolian, Chinese and Old Javanese language. Among them are classics like the Tibetan Sanskrit Dictionary, Material for a History of Tibetan Literature, Buddhist Iconography of Tibet and the Dictionary of Buddhist Iconography in 15 volumes. Lokesh Chandra was nominated by the President of India to the Parliament in 1974-80, and again in 1980-86. He has been Vice President of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, and Chairman of the Indian Council for Historical Research. Presently he is Director, International Academy of Indian Culture.

Preface

Tun-huang is the dream child of the Avatamsaka tradition of contemplation as it unfolded in Bamiyan. Both are marvels and wonders of the mind in their intensity and clarity, in their furling and unfurling of meditation. They are the quiet and kind strength of the bright and blushing light of nirvana. Here ecstasies were born, flourished and vanished. The classical anthology of Vidyakara, a dignitary in the Buddhist monastery of Jagaddala, cites a poem by Krsnabhatta.

The galaxy and the atom

both are matter: both exist.

Tun-huang and Bamiyan are the twin soul, wherefrom beauty of being filters through the sieve of sculptures, scrolls, murals and sutras, They are the spiritual environment of trees, rivers, dunes and hills, all radiant in the beatitude of the Middle Path of the Buddha. They invite us to a reformation of our civilisation that will begin with reflection on time. They are images of the divinity of man, the barefoot light on the fountain of our whole Being.

The first cave at Tun-huang was dug by Yueh-ts'un who was on his way to the Western Regions. Coming to Tun-huang with his disciples he was mesmerised by a sparkling river, parasol trees, poplars and willows, aroma of melons and other fruits, the miraculous waters of the springs nearby and the irridescence of the peaks of the Sanwei mountains. His disciple who had gone to fetch the sacred waters did not return and had settled down to dig a cave, paint its walls and create sculptures in the crushing majesty of the landscape. The air rustling with invisible presences was now inhabited by mysterious beings in the metaphysic of murals. The master Yueh-ts'un decided to create a sangha in the mountain among Singing Sands and gave up his pilgrimage to the West. It was the consecration of the endlessly changing aspects of nature as the light of cosmical consciousness which unfolds spiritual awareness, a spring of dazzling light no human words can describe. The first cave was opened in AD 366. The name Chien-fo-tung "Thousand Buddha Caves" derives from the legend that a monk dreamt of a cloud with the Thousand Buddhas above the valley.

The choice of a place for meditation had to be a site of pure and pleasing water which yields flowers and fruits. Lotus ponds, parks, divine shrines, waterfalls, caitya halls, quiet places, and other sites of natural charm are mentioned in the Vairocanabhisambodhi-sutra as appropriate for meditation (Wayman 1992:116, 312). The transparent veil of universal mystery has to the locus of contemplation wherein unfathomable depths are born of subtle self-analysis as the embodiment of enlightened meditation. The surrounds of Tun-huang provided the idyllic and serene ambience to forget the samsara and sink into meditation. Thus Mo-kao-k'u "Grottoes of Immeasurable Height", or Chien- fo-tung "Caves of the Thousand Buddhas" became the glittering Sumeru from the strategic commandery of Tun-huang "The Blazing Beacon" of the Han period. Its hundreds of caves were and are a pageant of Buddhist paradises with a sparkling galaxy of divine images, symbolising metaphysical spheres of inner experiences in a journey along the spiritual path.

The Avatamsaka sutras are a collection of thirty nine texts. Individual texts as well as the complete corpus were translated into Chinese from AD 167 to AD 798. The Tathagat- acintya-guhya-nirdesa gives the arising of the Thousand Buddhas. It was translated by Dharmaraksa of Tun-huang in AD 280. Thus the Avatamsaka was known in Tun-huang 86 years before the first cave was dug. The cult of the Thousand Buddhas must have been popular at Tun-huang, whence the disciple of Yueh-ts'un saw them in the clouds as well as Maitreya who is the first future Buddha in the system of Thousand Buddhas, while Rocana is the last or thousandth. Cleary (1983:9) speaks of "a pure mind entering into all realms of knowledge, a clearly aware mind perceiving the adornments of the site of enlightenment". As soon as the first cave was dug out, its adornment in multiplicity of colours was the first step. The essence of thusness (tathata) or the pure mind is "luminous or completely illumined" and inherently pure. Two functions of this essence are "oceanic reflection" and the complete illumination of the realm of reality (Cleary 1983:147). The Chinese word hua-yen for Avatamsaka means "flower ornament". The Avatamsaka arose and developed in the Bamiyan region and in the Lamkan Valley. The word Lamkan is the famous city of Ramma or Rammaka in the Pali texts and Ramyaka in Sanskrit. Dipankara the Buddha of the Past was born in the Rammavati metropolis. The last sutra of the Avatamsaka corpus is called Rarnyaka-sutra and it was translated into Chinese by Aryasthira in AD 388-407. It is also termed Gandavyuha. Ganda at the beginning of a compound means 'best, excellent' (MW). So Gandavyuha means "The Excellent Array, The Outstanding Cosmos", parallel to Sukhavati-vyuha. It connotes the paradise of Rocana whose adjective is Abhyucca-deua or Colossal Deity (see details in Lokesh Chandra 1997: CHI 6.32-51). Rowland 1971:38 says: "It would be safer to consider the lesser colossus as a work of no earlier than the year 200". Its inhabitants were of hardy Tokharian stock (Carter 1986:117). The Tokharians were present in Xinjiang as early as the second millennium BC. Rowland sees the Larger 175 feet colossus in its painted niche as a universal AdiBuddha such as Vairocana (Carter 1986: 121). He is actually Rocana the last of the Thousand Buddhas of the Avatamsaka. The motifs and themes of the Ming-oi of Kizil bear close resemblance to those of Bamiyan. Rowland 1971:42: " ... the resemblance of the various styles and techniques of the paintings at Bamiyan and Kakrak to the wall paintings of Kizil and Murtuq demonstrates ... the role of Afghanistan in the diffusion of influences to Central Asia and the Far East". The natural surrounds of Tun-huang are paralled to the Bamiyan river, its chinar trees, the entire landscape of hills and sprawling plains: "are of the most dramatic panoramas of Asia" (Rowland 1966:95) Tun-huang follows the pattern of the Bamiyan cliff honeycombed with vat complexes of cave chapels, some of them connected by galleries within, and along the front of the precipice. The disciple of Yueh-ts'un had a vision of Maitreya whence he sat out to dig the first cave. The gigantic painting of the Sun God in his chariot on the soffit of the niche of the Smaller Colossus at the eastern end of Bamiyan identifies the colossus as Maitreya. Maitreya and Rocana are 'Twin Buddhas' of the Avatamsaka. The Maitreya envisioned by the disciple refers to the Avatarnsaka which was well known by the translation of the irdesa by Dharmaraksa of Tun-huang. Yueh-ts'un and his disciples could have heard of the natural charm and iconic grandeur of Bamiyan and could have been on their way to Bamiyan. At Tun-huang

they visualised the crucial iconography of Bamiyan in the radiant clouds reflecting the Ten Bodhisattvas from the mystic clouds of the Gandavyuha. They settled down at Tun- huang to create a veritable paradise of Rocana Buddha in the transcendent adornment of the caves so that they are the realm of hua-yen "flower ornament" or as Maitreya says: "they know that all things are like reflected images, but the Bodhisattvas do not despise any world"(Cleary 1983:8).

This work describes and contextualises 143 paintings out of 277 in the National Museum, New Delhi. Some scrolls have faded leaving faint traces of colour and these have not been included. The art of Tun-huang has been phased in three periods. The first period with a marked influence of Gandhara cover four dynastie from AD 397 to 581. The second period span the Sui and Tang dynasties, from AD 581 to 907 when it attained its climax of aesthetic excellence, sumptuous paradises, sutras unfolding various spiritual worlds. The two large Vajrapani guarding the entrance of cave 427 in the early 7th century were an innovation, representing Narayana and Mahesvara as guardians. They came to be known as 'Two Kings' or Ni-6 in Japan, and are colossal sculptures. The Northern Colossus of Maitreya in cave 96 dated to AD 695 and the Southern Colossus of Rocana in cave 130 is dated AD 721. The third and last period pertains to the Five Dynasties, Sung, Hsi-hsia and Yuan, covering over four centuries from AD 907 to 1368.

The Tibetans ruled Tun-huang from AD 781 to 847 and they donated a number of caves with new architectural features, new subjects and new pallete of colours. The 'Emperor of Tibet' is shown in the paining of cave 158, which is the largest as it has a gigantic figure of Lord Buddha in nirvana. A little lower than the Tibetan Emperor is the Chinese Emperor. Large-size royal portraits were an innovation that was followed later on by their successor rulers of the Ch'ang and Ts'ao families. The Ts'ao family which came to rule Tun-huang in AD 906 had close marital relations with Khotan. The Ch'ang family celebrated the return of Tun-huang to the Chinese by the heroic victory of Ch'ang I-ch'ao. They sanctified his hallowed memory by huge portraits in cave 98. The King of Khotan and the Uigur Queen too are depicted in larger than life portraits. The donor figures increased, in contrast to the earlier caves where no regal representations are seen. Tun-huang was the diaspora of the Khotanese royalty, nobility, monks and others escaping from the genocide and scorched earth aggression of Islamic Kashgar. Tun-huang survived these ravages of religious fanaticism and it is celebrated in Chinese poems written on the walls of the caves.

The Tiger Monk has eluded identification as an individual. He represents a generic type

of monks who were experts in the martial arts and escorted itinerant bhiksus across long distances. The warrior-trained monks were to guard the holy relics, the treasures of shrines, and teachers of Dharma from robbers (Tomio 1994: 194). Combatant monks are mentioned in the Sarvastivada-Vinaya (T24), Ekottaragama (T2), and Udanavarga (T4). The Asokavadana translated by Fa Ch'uan in AD 300 lists 32 sacred places at which Asoka built a stupa. These include the hall at which young Siddhartha studied the martial arts.

The mudras in the Tun-huang paintings and murals need to be studied in detail. Though in keeping with the traditional iconography, at times they represent regional variants or more sophisticated versions of the classical gestures. For example, Waley says that the Buddha in Stein 518 has the right hand in vitarka-rnudra near the chest and the left lies horizontal below it. It is a painting of Lord Buddha granting fearlessness from evil and the gesture of argumentation (vitarka) does not accord with its function. We have identified it as the abhaya-mudra in kataka with the elegant rondure Gzasalea 'ring') of the hands. The left is in the dhyana-mudra, The abhaya and varada-mudras of Lord Buddha had been identified as vitarka by Waley due to their nexus with the annularity of the kataka. The mudras have been re-interpreted to accord with their ritual function.

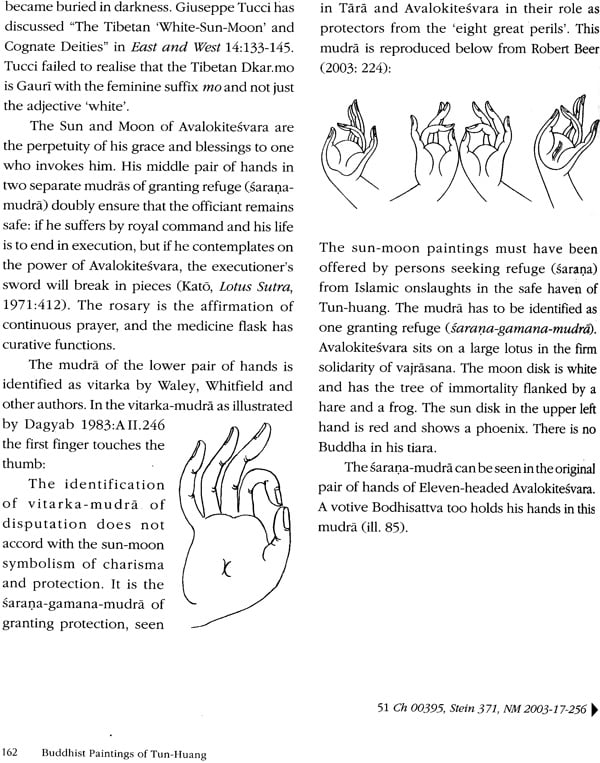

The mudra of the Sun-Moon Avalokitesvara is for granting refuge: it is the sarana-mudra. It has been identified anew from the mudra of Tara and Avalokitesvara in their role as protectors from the 'eight great perils' Casta- mahabhaya-trdna) .

We have spent glorious years on these scrolls of Tun-huang in their supernal appearances as a direct experience of a cosmic consciousness whose radiance fills centuries of Sino- Indian visions that sway, surge, throb, and hold rhythms of their own in the boundless wonder of impermanence. They are the wisdom that transcend? delusions, and the boundless mind that endures beyond the ups and downs of life's flow. From the visual domain they are the way to finer, subtler spheres of the arupa, an ascent from the world of space and time to the timeless omnipresence.

Contents

| Preface | 7 |

| TUN-HUANG OVER THE CENTURIES | |

| Terror of the terrain and quest of the beyond | 13 |

| The deep sands and imperial dreams | 13 |

| Permanent Chinese settlement in the Kansu Corridor | 15 |

| Yueh-chih introduced Buddhist Sutras | 16 |

| Yueh-chih Dharmaraksa (AD 230-308, active in 268-308) as the first great translator | 17 |

| The Sutra Route | 19 |

| Khotan as a source of jade and sutras | 19 |

| Tun-huang in a Niya document of AD 269 | 20 |

| TUN -HUAG: GALAXY OF DIVINE IMAGES | |

| Yueh-ts'un's disciple excavates the first cave in AD 366 | 21 |

| Avatamsaka and Tun-huang | 22 |

| Radiant memories in folk legends | 22 |

| Five-colour Maiden | 23 |

| Drops of amrta tipped off by Avalokitesvara in the river near Tun-huang | 24 |

| First period of the caves (AD 397-581) | 24 |

| Early Caves | 25 |

| Northern Wei (AD 439-534) | 25 |

| Sung-yun of Tun-huang | 26 |

| Western Wei (AD 535-556) | 26 |

| Northern Chou (AD 557-581) | 27 |

| Second period of the caves (AD 581-907) | 28 |

| Sui Dynasty (AD 581-618) | 29 |

| Early Tang (AD 618-704) | 31 |

| The Northern and Southern Colossi | 33 |

| Tun-huang as a strategic centre (AD 705-780) | 34 |

| Flourishing Tang (AD 705-780) | 34 |

| Middle Tang when Tibetans rule Tun-huang from AD 781 to 847 | 35 |

| Late Tang (AD 848-907) | 38 |

| Third period of the caves (AD 907-1368) | 39 |

| Tun-huang as the diaspora of Khotan after its Islamisation | 40 |

| Tiger Monk | 42 |

| Jade beauties to flying devis | 45 |

| Thousand Buddhas | 48 |

| TUN-HUANG PAINTINGS IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM | |

| Lord Buddha (ill. 1-10) | 51 |

| Famous Buddhist images (ill. 11) | 62 |

| Amitabha: Buddha of Infinite Light (ill. 12-21) | 82 |

| Bhaisajyaguru: the Buddha of Healing (ill. 22) | 99 |

| Maitreya Bodhisattva (ill. 23) | 106 |

| Avalokitesvara: the Supernal Compassion (ill. 24-35) | 108 |

| Eleven-headed Avalokitesvara (ill. 37-44) | 126 |

| Thousand-armed Avalokitesvara: Kinesis of the Measureless (ill. 45-51) | 138 |

| Sun-Moon Avalokitesvara (ill. 52-55) | 161 |

| Tiger Monk | 161 |

| Manjusri (ill. 57-59) | 170 |

| Ksitigarbha (ill. 60-63) | 174 |

| Five Transcendental Bodhisattvas (ill. 64-68) | 182 |

| Votive Bodhisattvas (ill. 69-130) | 190 |

| The Four Lokapalas (ill. 131-140) | 242 |

| Vajrapani Dharmapala (ill. 141-142) | 256 |

| Seven Treasures of the State (ill. 143) | 258 |

| LITERATURE CITED | 259 |

| CHRONOLOGICAL FOOTHOLDS | 264 |

| CHINESE DYNASTIES | 267 |

| CONCORDANCE OF CH., STEIN, NATIONAL MUSEUM AND BOOK NUNBERS | 268 |

| INDEX | 275 |