From Stone Quarry to Sculpturing Workshop- A Report on the Archaeological Investigations Around Chunar, Varanasi & Sarnath

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAO952 |

| Author: | Vidula Jayaswal |

| Publisher: | Agam Kala Prakashan, Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1998 |

| ISBN: | 8173200335 |

| Pages: | 317 (Throughout B/w Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 11.00 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 1.22 kg |

Book Description

The recognition of ancient stone quarries at Chunar hills with datable opigraphs was a startling discovery made by the author of this book, in the year 1990. The followup archaeological field investigations around Chunar and Varanasi, which were carried out between the years 1990 and 1994, have uncovered the entire process of stone carving which was prevalent during the historical period in the Ganga plains. Besides archaeological investigations, ethnological surveys were also carried out. As a result of which it has been possible to reconstruct the entire stone carving process, start from quarrying of stone blocks, their transportation to the centres of utility-carving of the sculptures, the finished products-nature of carving centres-interaction between the sculpturing centres and the main religious centres etc.

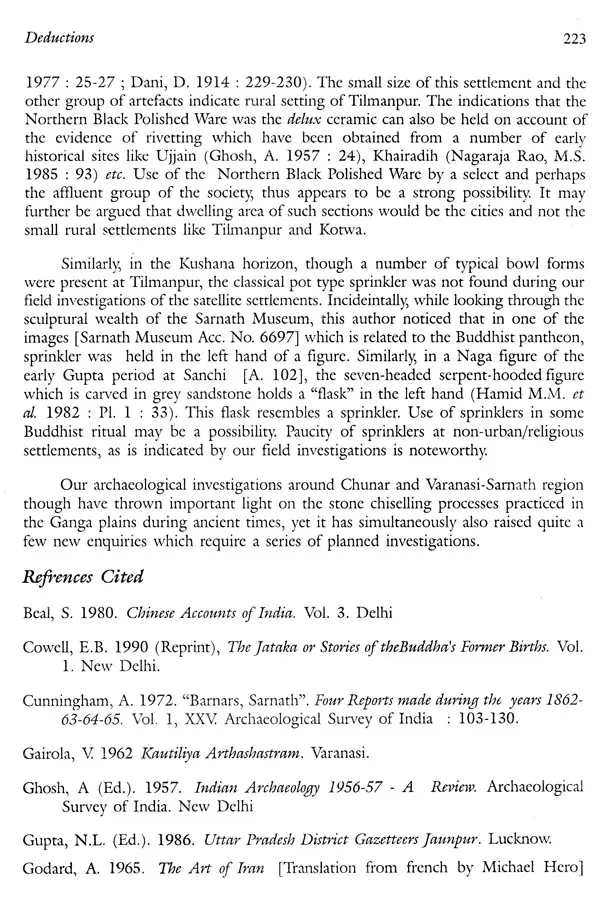

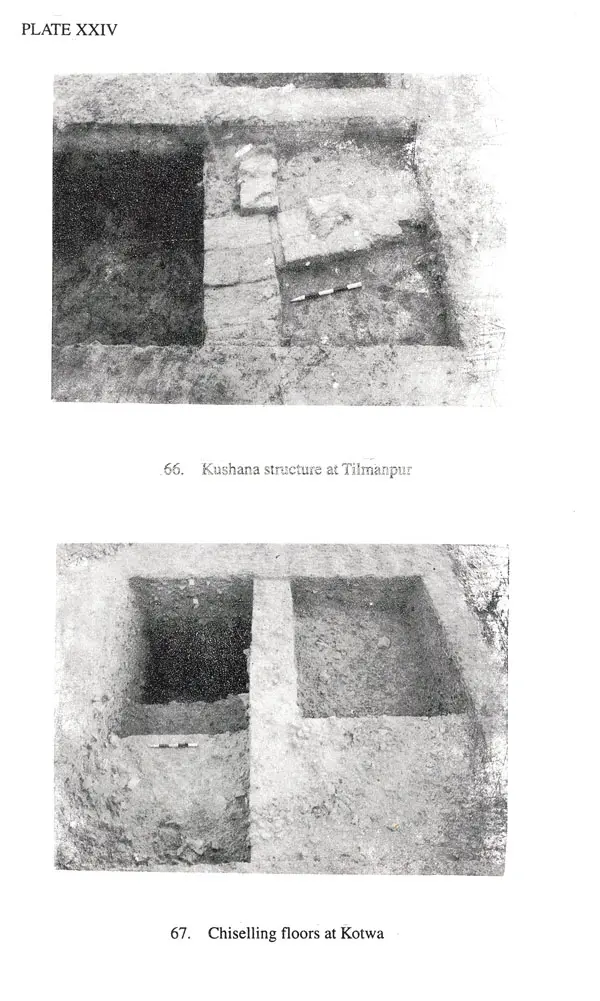

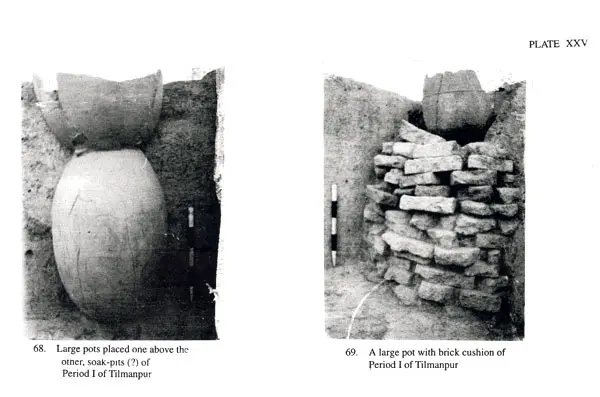

Some of the results of this study are very important, both for archaeologists and the art historians. For instance, it could be ascertained that, as is the case today. Chunar had been the principal lithic resource area during the ancient times. The epigraphs associated with the quarries provided firm grounds for dating quarrying operations in Chunar hills, between the Mauryan and modem times. The mode of transportation of the sandstone blocks which were quarried at Chunar, was by rolling down the hill slopes first and, then navigating these through the Ganga upto Varanasi. The discovery of a palaeo-channel joining Ganga with Samath, and the location of stone carving workshop sites along this route are the evidence which though are very significant are rarely preserved and found in the archaeological records. The present book, infact, incorporates reports of four set of field Investigations, that is-the quarry-area at Chunar, route of transportation i.e., the exploration around Varanasi region: excavated remains of Tilmanpur, a satellite settlement of Samath: Asapur-workshop cum-rural settlement; and, the workshop floors at Kotwa, where sculptures were actualy produced for use at Samath and Varanasi between the Second/First Century B.C. and the Medieval times. The discovery of more than hundred opigraphs and the multi-dimentional approach including scientific studies has added much value to this book.

Grand daughter of (Late) Dr K. P Jayaswal, Dr VIDULA JAYASWAL is presently teaching and guiding research in Ancient Indian History in general and Archaeology in particular at the Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi Dr Jayaswal was selected by the Government of India under the National Scholarship Scheme to study abroad and received specialized training in Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of California Berkeley, USA She also served the Archaeological survey of India Author of eight books, fire in English Palaeohistory of India, Chopper Chopping Component of Palaeolithic India, Kushana) Clay Art. An Ethno Archaeological View of Indian Terracottas and Paisra The Stone Settlement of Bhiar (last two in co-authoriship) and three text books in. Hindi-Bharatiya Itihas ke Adi Charan Ki Roop Rekha (Pura Prastar Yuga), Bharatiya Itihas Ka Madhya Prastar Yuga and Bharatiya Itihas Ka Nav Prastar Yuga She has also edited a proceeding of workshop which is published as Ancient Ceramics. Dr Jayaswal has to her credit more than fifty research papers, which have been published in the proceedings of International Symposia and various publications of repute. Her noteworthy field investigations are excavations of prehistoric sites at Lahariandih in Mirzapur and Paisra in Munger districts and excavation of historical settlement at Bhilari, and, surveys of pottery and terracotta producing centres of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar Her recent discovery of the Ancient Quarries of Asokan times and subsequent periods, near Chunar is a significant contribution to both Archaeology and History of Arts.

Significance of the discovery of ancient quarries at Chunar in the year 1990, was understood in a wider perspective, which included finding out answers to such histori cal enquiries, which were related, to the utilization of lithic medium. It was obvious from the published accounts that the Chunar sandstone was widely utilised throughout the Ganga plains for various kinds of carving activities such as making of icons, struc tures and other daily utility items. I was confronted with several questions at the very initial stage of this research project. Some of these are- what promoted Asoka, the Mauryan emperor, who is known to have initiated the use of stone for monumental activities, to select sandstone of Chunar hills when this stone is so abundantly available throughout the Vindhyan formations- what was the mode of transportation of large blocks of stone which were utilized at various ancient sites from the Mauryan period onwards what was the nature of lithic extraction and chiselling mechanism in this part of the country, etc. My studies revolved around some of these enquiries, as well as, understanding the entire mechanism of stone chiselling start from quarrying of stone blocks their transportation to the centres of utility carving processes of the sculptors, the finished products nature of carving centres interaction between the chiselling work shops and the main sculpture consuming centres etc. Both archaeological and ethno graphic studies formed part of this investigation, which was based on a well thought hypothesis.

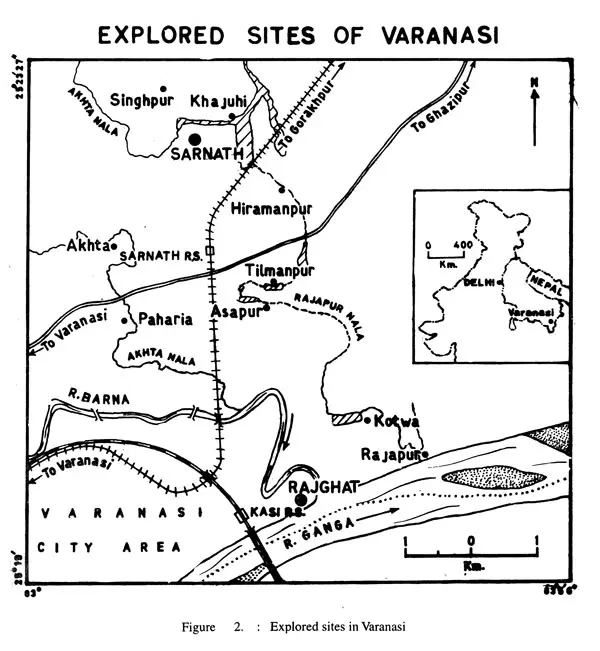

The four parametres of the proposed hypothesis were that the hilly part of Chunar was the main resource area for the supply of sandstone in the Ganga plains during ancient times the quarried stones were transported from the hills to the centres of utility through navigation Sarnath was one of the main lithic consuming settlements and, the lithic carving workshops catering to it's need were located by the side of the route of transportation of stone blocks. With a view to testing this hypothesis field investigations were carried out around Chunar, Varanasi and Sarnath between the years 1990 and 1994.

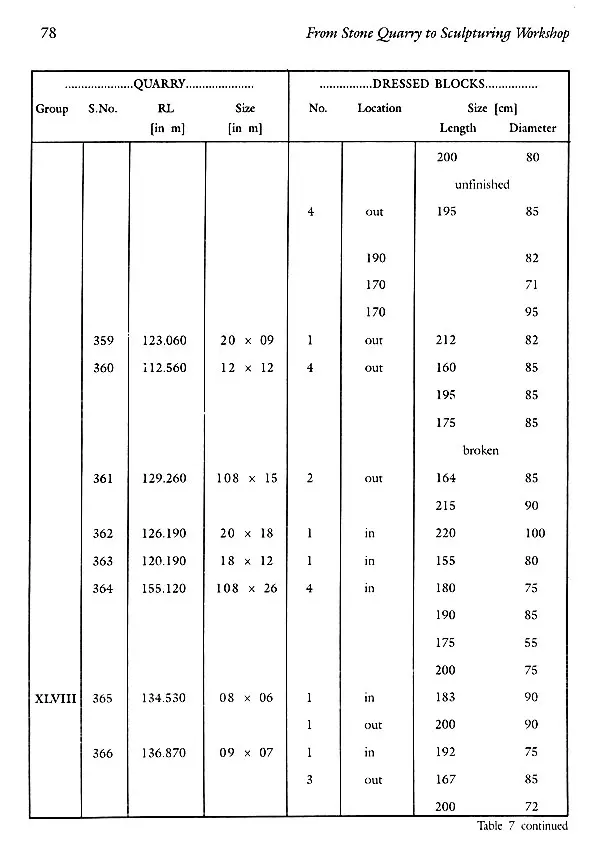

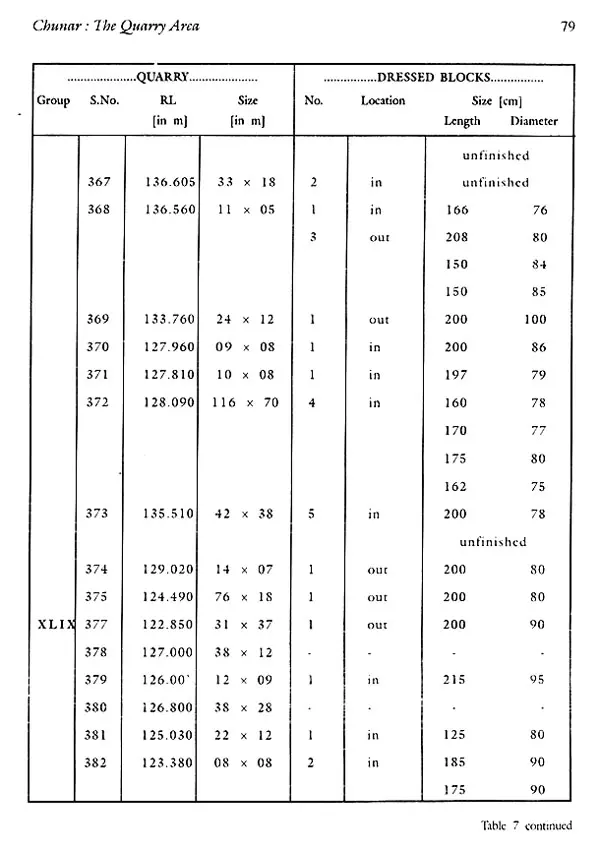

In view of the multi-dimensional nature of the project, application of different approaches was a necessity. For instance, the wide quarrying area of Chunar, with ap proximately fifteen square kilometres extension, had to be documented and surveyed intensively, and the inventories, which included details of quarries, dimension and loca tion of extracted blocks, location and nature of count-marks, location and nature of epigraphs etc., were recorded meticulously in a large site plan. Tabulation of statistical informations was deemed necessary for the production of this set of data [Chapter 2). Contrary to this, survey of the route of transportation [Chapter 3], was in the form of intensive exploration of water-channels and sites located in between the ancient city of Varanasi and the religious establishment of Sarnath. Section scrapings and small scale diggings, at satellite settlements of Tilmanpur, Asapur and Kotwa were aimed at un veiling the chronology and nature of these sites. Detailed report of the findings, alongwith analyses of artifacts obtained from these sites were compared with published remains of the urban and non-urban settlements of the neighourhood [Chapters, 4, 5 &6]. As a result of which rural bias of these feeding centres could be ascertained. The planning of the investigations and the research design of the present work [Chapter 1] included the posed historical enquiries, while the discussions on the findings provided plausible explanations to these and also help formulating deductions [Chapter 7], on some of the major issues of ancient crafts.

The entire exercise was very rewarding. For, the discoveries not only confirmed the prepositions by uncovering reliable sets of data, but, a number of other factors were also brought to light, which are important for understanding relationship of urban centres and their peripheral rural settlements of the historical period. For example, it could be ascertained that, as is the case to day, Chunar had been the principal lithic resource area since the Mauryan times. The epigraphs associated with quarries pro vided firm grounds for dating quarrying operations in Chunar hills, between the Mauryan and modern times. It was also ascertained that, right from the ancient period, the same method for extracting blocks of sandstone from the live bed-rocks was applied, which is in vogue to day. But, the mode or transportation of these blocks was different in the ancient period. As, contrary to the present day road transportation, the blocks were carved in cylindrical forms and were rolled down the hill slopes to the river Ganga, from where these were navigated upto Sarnath. Rajapur-nala, which is completely dried-up now, was the ancient drainage connecting Ganga with Sarnath. Location of small workshop sites like Kotwa and Asapur, further confirmed that this old-channel was the supporting route of transportation of the sandstone blocks from the river Ganga to Sarnath. Small rural settlements like Kotwa which were contemporary to ancient Varanasi and Sarnath having corresponding time-bracket of first/second century B.C.. to late Medieval periods were catering to the sculptural needs of the city and the reli gious establishment.

I would like to admit that with my own limitations it was not possible to do full justice to the multi-faceted nature of data which was encountered during the present study. I had to take help from a number of experts, whose contribution to this mono graph is significant. I wish to put to record my sincere appreciation and obligation to cach one of them.

Indeed it is with privilege that I write a Foreword to the archaeological report-From Stone Quarry to Sculpturing Workshop: A Report on the Archaeological Investigations around Chunar, Varanasi & Sarnath authored by Dr Ms Vidula Jayaswal of the Department of Ancient Indian History, Cul ture and Archaeology, Banaras Hindu University.

Varanasi for long has been known as the seat of culture/learning/religion. Varanasi being the oldest living city in the world has retained through ages the essence of Indian Culture. Archaeologists at Banaras Hindu University have substantially contributed in unveiling the history and culture of Varanasi depicted and described in our ancient texts as capital and cultural centre of the Kashi Janpada. Much more is indeed to be known about the history in this context and the present Mono graph of Dr Ms Vidula Jayaswal of Banaras Hindu University is yet another contribution which adds to our understanding of ancient Kashi Janpada vis-a-vis its capital. I complement her.

Archaeological studies ought to be based on logically formulated hypotheses. Dr Ms Jayaswal has demonstrated here that such an approach not only provided reliable base for the interpretation of ancient cultures, but it also brings to light such evidence as are rarely traced in archaeological context and often escape attention of investigators.

The discovery of ancient stone quarries at Chunar hills with datable epigraphs is indeed significant as it provides answers to a number of important questions about ancient Indian history. The followup archaeological field investigations around Chunar and Varanasi, which were carried out in the years 1990-1994, with a view to testing the hypothesis related to the ancient stone craft of this region unveils the entire process involved in stone chiselling operation. The discovery of palaeo-channel -the route of transportation of the big blocks of quarried stone from Ganga to Sarnath, and a chain of stone carving workshops lying between the ancient city of Varanasi and the religious centre at Sarnath are no less significant findings. This could be achieved through careful examination of archaeological remains by applying multi-dimensional approach, like-chemical examination of soil samples from the now dried up drainage around Sarnath, ethnographic studies of the present day image carving centres and intensive analysis of artefacts acquired from the excavations, etc.

One need not now speculate as to from where and how a block of sandstone was obtained? How was this heavy mass transported? Where the world famous Lion Capital of the Asokan times and other master pieces of sculptures housed at Sarnath were Carved ? Needless to mention that besides being a valuable documentation of the recent archaeological inventories this monograph would also give new directions to the study of ancient Indian arts and crafts.

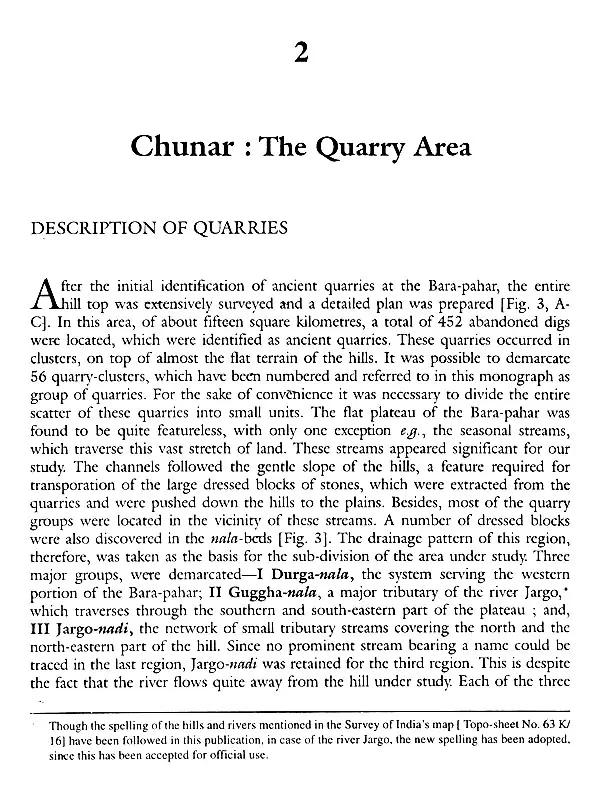

DISCOVERY OF ANCIENT QUARRIES

Ancient quarries in the Chunar hills were identified in the year 1990, when with a view to exposing Megalithic structures near Baragaon (Long.82 02 "E & Lat. 25° 04' N), a team of archaeologists of the Banaras Hindu University, led by PC. Pant and Vidula Jayaswal was conducting field inves tigations (Pant, PC. & V. Jayaswal. 1990). More than two decades ago, Pant had noticed a few large dressed cylindrical blocks of sandstone in this area, and was reminded of the Asokan columns. However, he could not pursue the matter further. Later, when he drew attention of this author to the dressed cylindrical blocks, she decided to find out what these blocks were. Even a cursory examination of the area revealed that these blocks were extracted from the sandstone beds and were dressed inside the dug rock-beds. There were a number of undressed and half-dressed blocks and heaps of debris in these quarries. The surface of each of the exposed stone was heavily patinated and bore ancient appearance. It was therefore, not difficult to identify these remains as abandoned quarries. The question, however, was whether these quarries were of any historical value.Enquiries from the local inhabitants of Baragaon, primarily a village of the stone cutters, revealed that these blocks were not modern and were lying in this region since time immemorial. Stone quarrying is being carried out in large scale in these hills, and we were informed that the modern stone cutters do not extract any slab from the old quarries, since according to them, continuous exposure is supposed to have converted the stones from these quarries so hard as to make these completely unusable. Incidentally, the term mara patthar [dead stone] is used for these blocks and jinda patthar for the blocks which are acquired from the fresh digs by the modern stone cutters of this region. Besides, the stone which is supplied from Chunar these days is in the form of flat slabs which are called Partia and cylidrical blocks are no longer being quarried. Encouraged by this information, an intensive search was made for further clues which proved to be very rewarding. Very soon short epigraphs on a few dressed blocks were discovered and one of this was identified at the very outset as kharoshti script of the Mauryan times (Pant, PC. & V. Jayaswal 1990-91:50). Besides, engravings in Brahmi script bearing Mauryan, Kushana and Gupta features and Nagari labels of the medieval period were also found, subsequently Discovery of these inscriptions not only provided definite evidence for dating these quarries, but also revealed that the ancient quarries of the Chunar hills were in use for a long period of time between circa third century B.C. and the medieval period.

The evidence from Chunar has unravelled complete picture of lithic ex ploitation and mode of transportation from the hills to the major settlements in the Ganga plains during the ancient period (Jayaswal, V. 1994). For example, the abandoned quarries suggest that suitable blocks were extracted from the sandstone beds lying usually on the top of the flat terrain of the hills. The blocks were thereafter chiselled in the quarry itself to give them cylindrical shape resulting generally in thick accumulation of chiselling debris. Some of the undressed and half-dressed blocks were also left unused. Besides, in each quarry, a flat rock with short lines numbering at times in hundreds was also recorded. These were identified as quarry records of the blocks made ready for transportation (Pant, P.C. & V. Jayaswal. 1990). Once these large blocks of sandstone, which on an average measured in length around two metres and in diameter around one metre had been dressed, these were ready for trans portation. It is apparent that the ancient stone workers had developed an ingenious method of transporting these unwieldy blocks to various centres where required. For instance, the blocks were just rolled down the hills to nearby valleys and from there to the banks of the Ganga; these were then loaded on suitable rafts for further transportation. Once loaded, these could easily be carried both up and down stream. The practice must have started during the Mauryan period and seems to have continued even in the subsequent periods because of the suitability of the method. It may be recalled that, as recent as the laying of the railway lines, navigation was the main mode of trans portation of the utility items in the Ganga plains (Johnston, J. 1933:32). In fact, even today large boats carry stone slabs from Chunar to various centres in the middle Ganga plains. Archaeological evidence for such a practice was obtained around Chunar in the form of a good number of cylidrical blocks of quarried sandstone. Which were not only found along the dried up wala descending from the hills, but also upto the banks of the Ganga around Chunar township, where some of them even now lie partly submerged in the river.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages