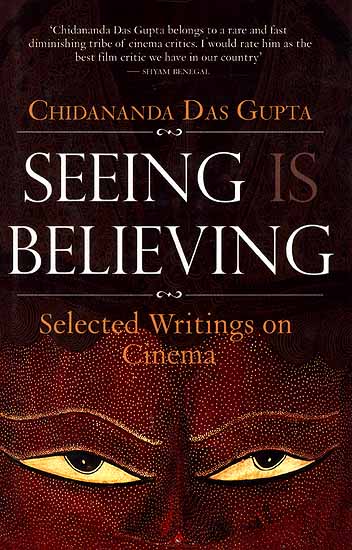

Seeing Believing (Selected Writings on Cinema)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDC345 |

| Author: | Chidananda Das Gupta |

| Publisher: | Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd. |

| Edition: | 2008 |

| ISBN: | 9780670082063 |

| Pages: | 304 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| a50_books | |

| Other Details | 8.9” X 5.8” |

Book Description

Seeing Is Believing brings together some of Chidananda Das Gupta’s finest writings on the subject of cinema over the last sixty years. In these highly informed and thought-provoking essays he addresses diverse themes like the origins and history of the parallel cinema in our country; the national film awards; the unique interface between politics and film in India; the portrayal of women, sex and violence in our films; and the quintessentially Indian contribution to movies – the song. The collection to includes definitive studies of the work of five of the nation’s finest film-makers – Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Adoor Gopalakrishnan ad Shyam Benegal.

Consistently erudite and engaging, Seeing Is Believing windows to the journey of Indian cinema over the last six decades.

An authority on cinema, Chidananda Das Gupta has spoken on the subject at diverse forums and has written articles in various celebrated journals, including Cinemaya, Iconics and the British Films Institute’s Sight and Sound. He has been editor of the Indian Film Review and the Indian Film culture. He is the author of Talking about Films, The Painted Face: Studies in India’s Popular Cinema and The Cinema of Satyajit Ray and other books. He directed the acclaimed feature film Bilet Pherat (1972) and a number of documentaries, including Portrait of a City (1961) and The Dance of Shiva (1968). He was honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Osian Film Festival, 2004.

Chidananda Das Gupta lives in Calcutta.

My own writing was inevitably coloured by these predilections. Cinema had been born in the industrialized West, I argued, and had achieved its heights there. The course of Indian cinema would be linked to industrialization in what was now predominantly an agricultural economy. The form Indian popular cinema had acquired was a distortion. It would correct itself as the country industrialized itself. For formal growth, we should look to the West, and for understanding the working of popular Indian cinema of the time we would have to take recourse to sociology.

By and large India’s art cinema has derived its inspiration from the west – America storytelling, Russian revolutionary innovations, Italian neorealism, French New Wave, and so on.

For a hundred years Bollywood has expressed, experimented with and explored social concerns affecting a country caught in the throes of change. This perception is far removed from the equation of popular cinema with pure entertainment. This book brings together many of my writings of this nature. Thus the chapter on cinema and politics (‘Cinema Takes Over the State’) analyses the unique way, unparalleled in the world, politicians have used cinema consciously and deliberately in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. It explains how this experience is deferent from that of Ronald Reagan in the United States. Social concerns have also paralleled the political throughout India. These are amply reflected in ‘Cinema Takes Over the State’, ‘Seeing Is Believing’, Why the Films Sing, and other chapters. Some of the films are so involved with social problems that it is hardly possible to describe them as entertainment. No wonder sociologists have been increasingly drawn into discussions on popular cinema. Indeed, their deliberations on social concerns of this cinema have been singularly unrelated to their artistic aspirations. It is odd to find that the so-called art cinema should wear social problems on its sleeve while pure entertainment should conceal its social concerns in a secret chamber of its heart.

Sixty years is a long time, and an active scribe can turn out a considerable amount of writing during this period. The problem is often one of making a representative selection. I am immensely grateful to Kalyan Ray for helping me in this task. Like many commentators on cinema Kalyan is a professor of English literature (I myself began life that way). I am no less indebted to Diya Kar Hazra of Penguin Books for steady interest in bringing this effort to fruition.

| Introduction | vii | |

| 1. | Of Margi and Desi: The Traditional Divide | 1 |

| 2. | Seeing Is Believing | 24 |

| 3. | Why The Films Sing | 33 |

| 4. | Cinema: The Realist Imperative | 44 |

| 5. | Woman, Non-Violence and Indian Cinema | 57 |

| 6. | Precursors of Unpopular Cinema: A Parallel View of Indian Film History | 73 |

| 7. | A Word on Awards | 98 |

| 8. | Film As Visual Anthropology | 107 |

| 9. | The Crisis in Film Studies | 117 |

| 10. | How Indian is Indian Cinema? | 132 |

| 11. | Cinema Takes Over The State | 145 |

| Notes on Five Directors | ||

| 12. | Satyajit Ray: I. The First Ten Years | 193 |

| II. Modernism and Mythicality | 205 | |

| 13. | Ritwik Ghatak: Cinema, Marxism and the Mother Goddess | 220 |

| 14. | Adoor Gopalakrishnan: The Kerala Coconut | 241 |

| 15. | Mrinal Sen: Loose Cannon | 250 |

| 16. | Shyam Benegal: Official Biographies, Personal Cinema | 266 |

| Notes | 280 | |

| copyright Acknowledgements | 285 | |

| Index | 286 |