Credit, Rural Debt and The Punjab Peasantry (1849-1947)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAZ893 |

| Author: | Sukhdev Singh Sohal |

| Publisher: | Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| ISBN: | 9788177701739 |

| Pages: | 210 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 330 gm |

Book Description

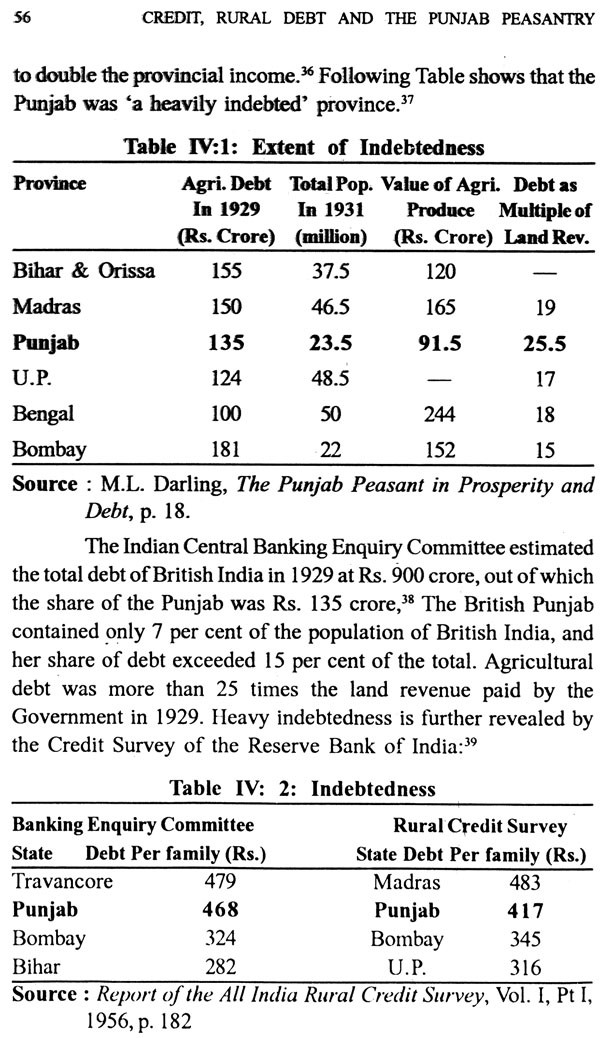

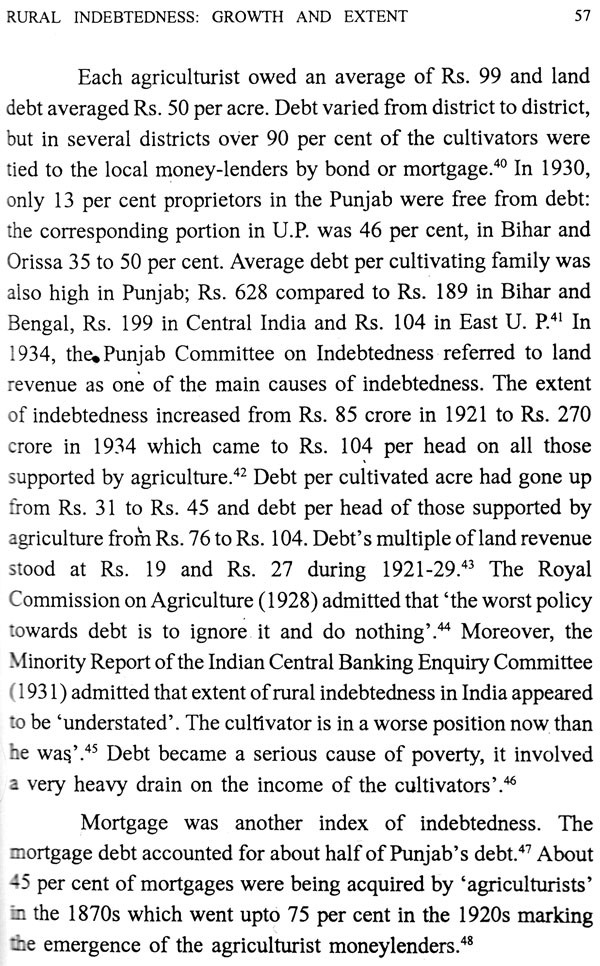

Debt perpetuates economic inequalities. The colonial administrators took it as a corollary of prosperity which could be in the case of landlords and surplus producing peasants. A considerably higher proportion of those households in debt sere tenants and marginal farmers, a fact, the colonial administrators underestimated. Moreover, the Punjab Committee on Indebtedness (1934) referred land revenue as one of the main causes of indebtedness in the Punjab. The British Punjab contained only seven per cent of the population of India and her share of debt exceeded sixteen per cent of the total, thus, making the Punjab 'a heavily indebted province. The problems of Punjab peasantry manifested in the form of non- availability of credit at lower interest rates, rural indebtedness, litigation and alienation of land from producers to non-producers. The main objective of the colonial state was to perpetuate imperial hold and further the process of extraction and exploitation.

Peasant life is full of adventure, adversity and aspirations. Close to nature, the peasant, mixing a seed with soil turns magician as the plant he nurtures bears fruit. He toils endlessly and purposively and has been doing since the human beings have moved beyond food-gathering stage. Peasantry has reached at the cross-road. A paradox is unfolding upon the peasantry as a profession: Produce and perish. My interest in the peasant studies corresponds to my social existence. Belonging to a peasant family, I watched closely agrarian processes: tilling, sowing, nurturing, harvesting and marketing. As a child, I could humbly contribute to the joint family by tending cattle, picking chilies, cutting fodder and serving food and water to the workers. Each function deserved devotion and dedication. Before the coming of the Green Revolution, by the mid-1960s, I could feel fears of uncertainty of crop and fury of nature. This instinct of survival, I still cherish especially amidst adversities. Then followed the march of food production during the Green Revolution. Mechenisation and monetisation of peasant economy followed. The scale mattered most. My joint family could spare me to move forward. In a way, this is my debt to all the peasants.

**Contents and Sample Pages**