K.R. Srinivasa Iyengar

Book Specification

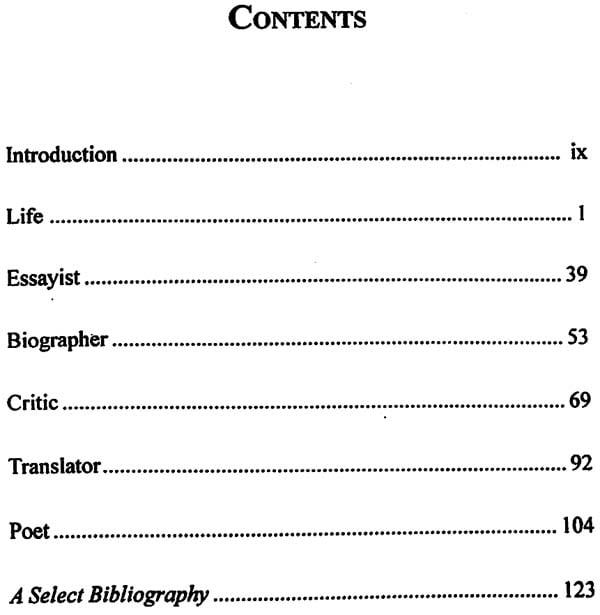

| Item Code: | NAQ499 |

| Author: | Prema Nandakumar |

| Publisher: | SAHITYA AKADEMI, DELHI |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2008 |

| ISBN: | 9788126026456 |

| Pages: | 135 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 100 gm |

Book Description

K.R. Srinivasa lyengar (1908-1991) was an Acharya in the great Indian tradition. After teaching in Valvettiturai (Sri Lanka), Belgaum and Bagalkot, he moved to Andhra University, Waltair, Andhra Pradesh in 1947 as Professor of English, and was Vice-Chancellor during 1966-68. Elected Vice-President, Sahitya Akademi in 1969, he retired as Acting President in 1978. Recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Award, the B.C. Roy Award and the Kalidas Nag Award, he was elected Fellow of the Sahitya Akademi in 1985. Widely traveled in India and abroad, he was Visiting Professor of English at the University of Leeds in 1959, and received the Doctor of Letters, honoris causa, from the Sri Venkateswara and the Andhra Universities.

Dr. lyengar was a scholar and a prolific writer. His works include the standard biographies of Sri Aurobindo, and the Mother of Sri Aurobindo Ashram and critical studies of Lytton Strachey, G.M. Hopkins, Shakespeare and Francois -Mauriac. Some of his learned articles have been collected in The Adventure of Criticism, Mainly Academic, Dawn to Greater Dawn and Two Cheers for the Commonwealth. His authoritative and comprehensive Indian Writing in English reveals his strivings as the founder of a new discipline in Indian letters. He made his mark as a translator too and has rendered into English Basaveswara, Tiruvalluvar and Tirumoolar. His translation of Sundara Kanda has been published as The Epic Beautiful.

It was in the seventies that Prof. lyengar turned to writing serious poetry. Apart from anthologies of short poems like Tryst with the Divine, he also wrote the epics Sitayana, Sall Sapthakam and the Bhagavata-inspired Krishna Geetam.

Preina Nandakumar (b. 1939) obtained her Ph.D for her study of Sri Aurobindo's Savitri. A creative writer, critic and translator, she writes both in Tamil and English. Her recent publication is an English translation of the ancient Tamil ethical text, Eladi.

I am grateful to the Sahitya Akademi for giving me this opportunity to write a monograph about my father, K.R. Srinivasa Iyengar. Being a daughter and disciple to him was a unique adventure, and I learnt what was really meant by the term "gurukulavasa" in our Vedic heritage. There was love which went along with stern discipline; laughter that laced a high seriousness in conversation and the learning process. Also the terror and ecstasy of discovering the riches in the Acharya's "Sree-Kosa" (library). Above all, I learnt simply by being a listener during our long walks. If it was not literature, history or politics, it was classical Carnatic music, for lie was also my music teacher.

Though my marriage took me away from the natal home, we corresponded regularly and my parents spent all their holidays with us. My studies and writing were shaped by father in every way. I never failed to marvel at the manner in which he worked long hours, writing, typing, and correcting. He was the Ideal Scholar and role model for my brother Ambirajan and me. For us, as indeed for almost everyone who came in close contact with him, he contained continents. He was a great letter-writer too and corresponded with some of the famous names of the twentieth century.

I hope the present monograph will give the reader an idea of the large body of his literary work, and its particular significance to life and letters. There are other areas in which he excelled too: as a teacher, educationist, editor and commentator. All this and more will have to wait for space in a publication with larger scope.

I may mention here that my mother used to help with the proofs for my father's publications and was herself a writer and translator. It gives me some satisfaction that she read the earlier chapters before passing away in May 2007 and was happy that I was engaged in this task.

My thanks are due to my daughters Ahana and Bhuvana and son Raja who went through the entire manuscript and suggested improvements. My grateful thanks are also due to my husband Nandakumar and sister-in-law Prabha Ambirajan for the love and care they brought to my parents. Dr. Ila Rao (my father's student and my teacher) and other members of my extended family have been very enthusiastic about this publication. To all of them, my thanks.

Indian literature is unequalled in its vast, constantly expanding parameters. No one has been able to correctly assess its age, either. Like the sub-continent, Indian literature remains the oldest and yet the youngest, thanks to the constant renewal that has been its good fortune since time immemorial. For the nation never closed its doors on external inspirations. The ancient Vedic singers compared it to a rich nest of free-moving birds:<> The loving sage beholds that Mysterious Existence

wherein the universe comes to have one home:

Therein unites and therefrom issues the whole:

The Lord is warp and woof in created beings.'

Yatra viswam bhavati eka needam! The Vedic canon seems to be the oldest among the surviving literatures of India and presents the basal structure for all that has followed. After the Vedic Age, we held on to Sanskrit as a single strand up to the concluding centuries of the first millennium. It was a rich and opulent age for Indian literature with the roll call of honour including brilliances as Bhasa, Kalidasa and Bhavabhuti.

Even here, we have Pali and Ardhamagadhi literatures. During the last one thousand years, there has been a growth of several regional literatures in the Indian clime, broadly docketed to about twenty languages as officially recognized ones. Actually, there are more than two hundred languages and may be not less than six hundred dialects in the Indian sub-continent.

So many literatures! How are they Indian then? Are they but `Marathi literature in India' or 'Malayalam literature in India'? The problem exercised K.R.Srinivasa lyengar's mind deeply throughout his life. He did not want to be numbed into inactivity ) by the variety and vastness of works produced in India. Nor was he prepared to be dogmatic and say India's culture was one and indivisible and undisturbed since the Vedas. India was no Babel of Tongues. It was not a monolith that admitted nothing new into its structure either. More than half a century ago. He compared Indian literature to a rich garden:

"Nature, man, the march of history, the play of chance, all have taken a hand in the making of this garden. One marks the individual trees, one is attracted by the flowers here, the fruit there; but one takes in no less the garden as a whole, admiring its relations and proportions, and inferring its unifying and harmonizing soul. However dazzling in its richness or baffling in its complexity, modern Indian literature is but the outcome of a long, long process of evolution and growth."

Every moment of lyengar's life was spent with a rare concentration in this marvellous orchard, and hence reading and writing became his life-long yoga. He was conversant with the writings from the Vedic times to his own day. English was his major instrument. However, he knew Sanskrit and Tamil well and this enriched his English style in a big way. Also, he constantly kept widening his parameters by reading translations from other languages. Nor did he confine himself to creative literature alone. He was equally at home in other disciplines like philosophy, history, science and mathematics.

While all this reading went on along with journalism, short fiction, translation, research papers and exegesis, lyengar was always crystallizing his thoughts on what he read. Quite early in his life he noticed that if there could be a different élan for Hindi or Bengali literature within the confines of India, a like novelty may be traced in English writing by Indians. This did not seem to him an extension of English literature like Australian or Canadian literature. He found that when the Indian wrote in English, the author came carrying a rich tradition from Vedic times onwards that gave the work a distinctive flavour not to be had in other English writings. This thought led him to posit such writing as Indo-Anglian or Indian Writing in English. During the last half a century it has stabilized its place as an individual entity among Indian literatures. Iyengar himself has thus become the Father of Indian Writing in English!

His work was not done at one stroke. He undertook a painstaking search for English publications and avidly wrote out full-fledged notes when he could not buy a book. But it was exciting and educative to discover so many writers wielding the foreign language almost to perfection even from the eighteenth century onwards. In the process, lie was able to place writers like Sri Aurobindo in the map of world literature. Sri Aurobindo's Savitri was the greatest inspiration in his life. He was astonished that so early in its history, Indian Writing in English could produce a full-fledged epic poem. After several decades engaged in the "other harmony of prose" to write his critical and biographical works, came the day in the evening of his life, when he began writing serious narrative poems enriching the new discipline with three gems: Sitayana: the Epic of the Earth-born, Saga of Seven Mothers: Sati Sapthakam and Krishna-Geetam. Altogether, a true creative historian and artist of the Indian clime.