Manda Oral Literature

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAX332 |

| Author: | B. Ramakrishna Reddy |

| Publisher: | Central Institute Of Indian Languages, Mysore |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2009 |

| ISBN: | 8173421830 |

| Pages: | 220 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 260 gm |

Book Description

The Kondhs constitute a homogeneous tribal group in Orissa that speak the Kui Kuvi, Pengo, Manda and Indi-Awe languages. The languages of the Kondhs have become endangered under the impact and influence of the regional major languages and their dominance in the visual electronic media. Manda Oral Literature presents the myths, festivals, rituals, life cycles and stories of the Manda-Kondhs, reflecting the socio-cultural conventions prevalent in the community, its traditional wisdom, practical knowledge, relationship with nature, worldview and philosophy of life. The documentation is a step towards . preservation of the tribal socio-cultural and linguistic heritage for posterity that in turn provides a unique identity to the community. The tribal lore collected in. the Manda Oral Literature will be immensely valuable to the Manda-Kondhs and general readers as well as to scholars of linguistics, literature, anthropology, narratology, folklore, sociology, oral history and education.

B. Ramakrishna Reddy is a distinguished linguist, with specialisation in tribal languages and literature. He has conducted extensive linguistic Fieldwork on the tribes of central and southern India including the speakers of Kuvi, Manda, Indi-Awe, Gadaba, Irula, Parengi (Gorum), Kharia, Adivasi Oriya and Banjara (Lambadi) languages. He has held academic positions at Annamalai University, Central Institute of Indian Languages, Central Institute of Hindi, Osmania University, PS. Telugu University and Dravidian University. He has been associated with the Adivasi Academy, Tejgadh since its inception.

Prof. Reddy's publications include Kuvi Phonetic Reader (1974), Localist studies in Telugu Syntax (1986), Kuvi-Oriya-English Dictionary (1995), Kuvi Folk Literature with Oriya and English Translation (2000) and Tribal Lore of South India (2004). te has also edited Studies in Dravidian and General Linguistics (1992), Dravidian Folk and Tribal Lore (2001), Agreement in Dravidian Languages (2003), Word Structure in Dravidian (2003) and The Tribal and Minor Dravidian Languages: An International Bibliography (2005).

During the last academic year, the Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) had offered a substantial grant to Bhasha Research Centre for a set of four books, which are now ready to be published. These are - :

- Tribal Literature of Gujarat by Nishaant Choksi

- Manda Oral Literature by B. Ramakrishna Reddy

- Manda-English Dictionary by B. Ramakrishna Reddy

- Indigenous Peoples: Responding to Human Ecology by Lachman M. Khubchandani

Although the Government of India and especially the Ministry of HRD can create an academic environment conducive to application-oriented research, it cannot force its agenda on the research academies and bodies, sincere and dedicated professionals. Many of them want to help the smaller communities solve their problems in the sectors of health, education, preservation and promotion of cultural heritage and related social problems. The materials produced have to be sensitive to the legitimate needs of the individuals and communities with which they work. This is exactly what is being done by Bhasha, Baroda. Earlier, CIIL collaborated with them in bringing out pictorial glossaries and other materials in a large number of Bhili dialects.

Among the books being published, the importance of a dictionary is undeniable. With the advent of literature, words acquired new meanings as well as usage. To help readers to have an entry into the world of unknown words, the publication of dictionaries is essential. Since many tribal regional languages have started producing literature these days, an introduction to all of them from Gujarat is very useful. Similarly, orality keeps the debate on in literary circles, and to that extent the work on Manda oral literature is particularly welcome. The last of these is a treatise by Professor Khubchandani, who has been at the forefront of tribal studies for the last fifty years, and is an untiring crusader for the tribal cause. In that respect, his work on Human Ecology is extremely important.

What are the challenges for a Tribal Languages researcher in India? In many cases, the tribal habitats are inaccessible and almost one-third of them still live below the poverty line. Consequently, hunger and prolonged fight with day-to-day adversities take precedence over education as effects of development are either lacking or are sub-standard. Abject poverty of these people compounds the problem. And yet, they are creative and culturally sensitive, and may even turn out to be more civilised than the so-called civil society. The situation has vastly improved after ‘Tribal Affairs’ received a special focus and a special ministry was set up and the sectoral programmes, such as health, education, poverty alleviation, women & child development etc., are looked after by the concerned Central Ministry that continues to administer its programmes.

CIIL has always been active in the field of tribal and border languages, and is engaged in endangered languages research these days. This is not something that can be achieved by one institution alone, no matter what its funding for such activities would be. The main dearth is in the human resource that is in plenty with organisations such as Bhasha. This is what makes the collaboration worthwhile. I am sure that research scholars, faculty, government officials as well as common readers would like these books, and will send us their feedback to improve upon these texts in later editions. More importantly, these books are going to be acceptable by all those who are members of these communities. That will give us all a great satisfaction.

Central India is the homeland of many tribal communities whose native languages belong to the Dravidian, Austro-Asiatic or Indo-Aryan family. The Kondh is one such prominent tribe living in parts of Orissa and Andhra Pradesh and speaking a group of Dravidian languages. They are also found, though in fewer numbers as migrant labourers in Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, West Bengal and Assam.

The name of the tribe under study is written with different spellings such as Kondh, Khond, Khondh, Kandha, Kond or Kondo. Here, the form Kondh is adapted as a representative term. These labels for the tribe are said to be derived from the Telugu (Dravidian) word konda which means ‘mountain’ or hill’. Kandhamal, that is a district in Orissa can be interpreted as a combination of Telugu konda and Proto-Dravidian malat ‘mountain’, providing the meaning ‘hilly region’ and hence ‘hill dwellers or hill tribe’.

Many of the tribal communities in Orissa and adjoining areas are referred to as Parjas, ‘the people’. Accordingly, the Kondhs are known as Kondh Parjas on par with other tribal communities like Pengo Parja, Bondo Parja, Parenga Parja and so on. In the complex multilingual context of India, many ethnic communities may speak a single language as their home language. But in the case of the Kondhs the situation is quite unique for ‘Kondh’ is a generic term standing for a single tribal community that is divided into five linguistic groups depending upon the home language or mother tongue of a particular section. Thus, there are five Kondh languages distributed chiefly, if not exclusively, across the area given here as under:

- Kui — Phulbani (Kandhamal), Boudh and Ganjam districts of Orissa

- Kuvi — Koraput and Rayagada districts of Orissa; Visakhapatnam, Vizianagaram and Srikakulam districts of Andhra Pradesh

- Pengo -— Nowrangpur (Nabarangpur) and partly Kalahandi district of Orissa

- Manda — Kalahandi district of Orissa

- Indi-Awe — Rayagada district of Orissa

These linguistic groups are also called Kui-Kondh, Kuvi- Kondh, Pengo-Kondh, Manda-Kondh by the native speakers whereas the outsiders refer to them collectively as Kondh Parjas.

Manda and other Kondh languages belong to the South- Central sub-group of Dravidian family. The Manda Kondhs live in the highlands of Thuamal Rampur Block in Kalahandi district of Orissa. There are about sixty villages inhabited by the Manda community; the population of each village ranges anywhere from 25 to 300 persons. The total number of Manda speakers as estimated during our visits is between 4,000 to 5,000. The Census of India with effect from 1971 does not record any language that has less than 10,000 mother tongue speakers. Consequently, Manda is not mentioned in the government records. The community is currently living in isolated highlands and retains its distinct mother tongue. But the language has become endangered due to the impact of Oriya, the major inter-group medium of communication. The Manda speakers are bilingual and are fluent in both their home ‘language as well as Oriya.

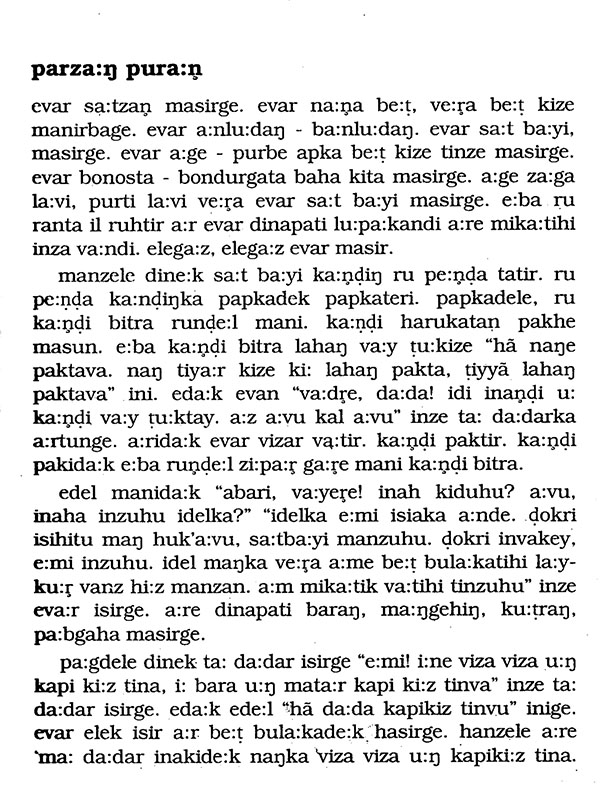

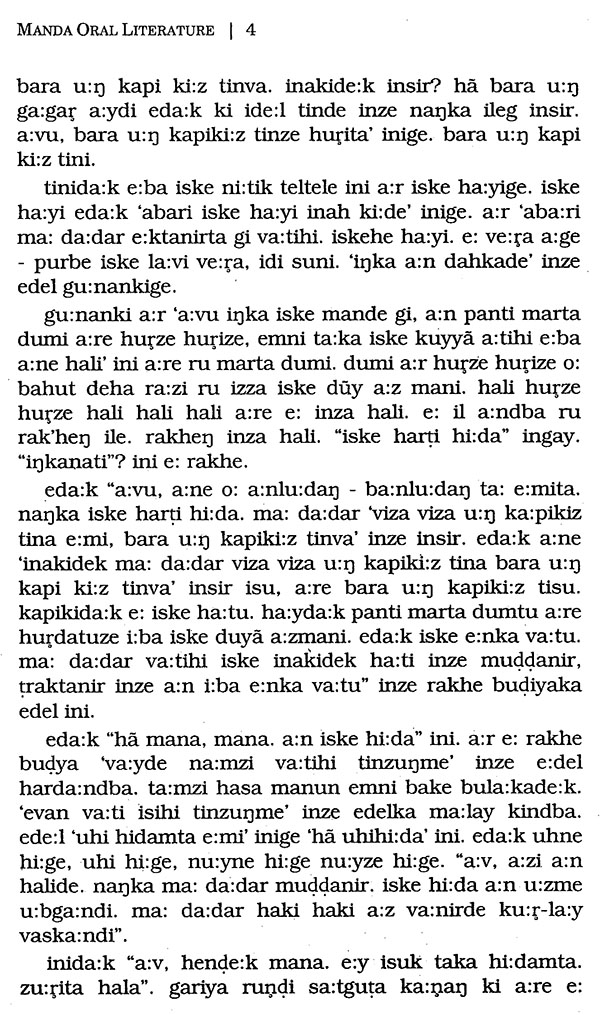

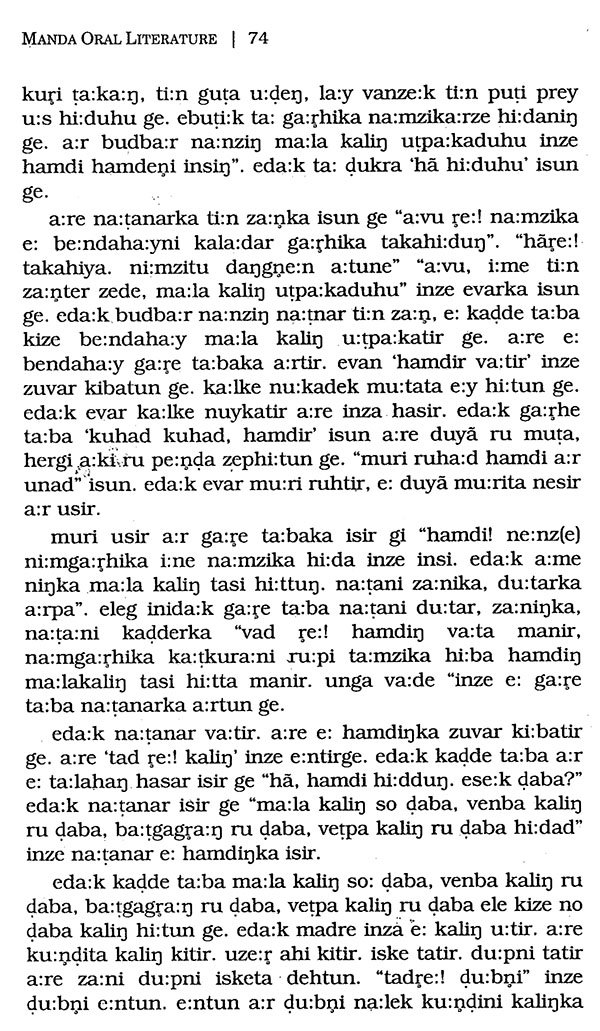

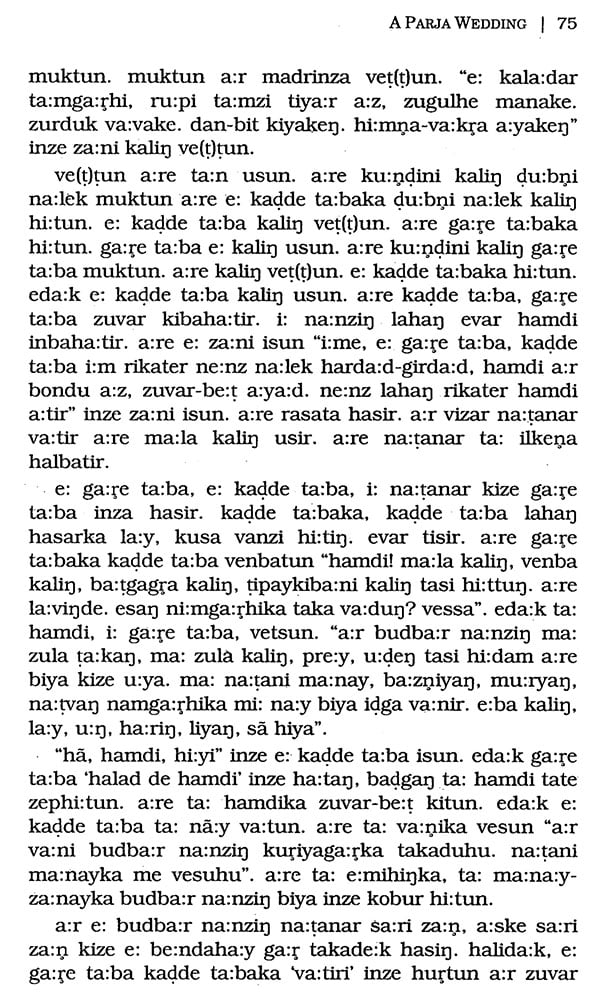

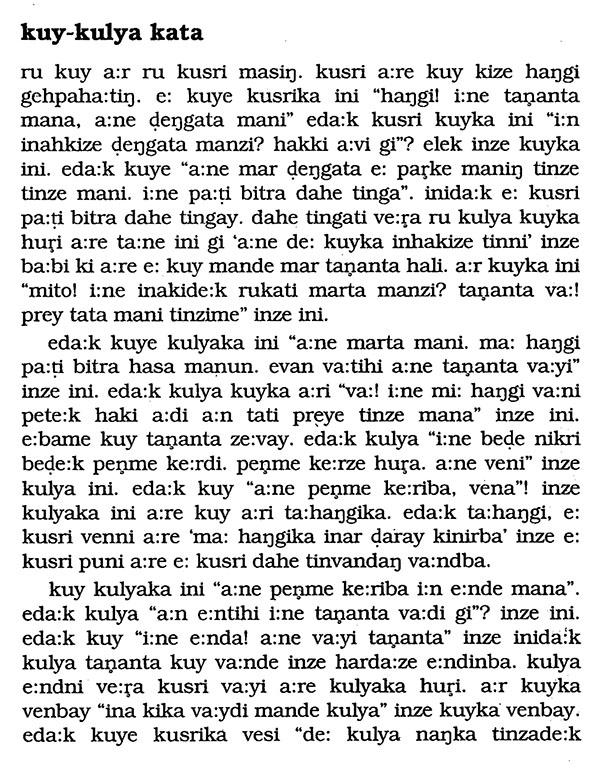

The Manda oral literature in this volume was dictated by our principal informant Jabya Sanatan Majhi (Sanatan hereafter). He hails from Katkura village, situated at a distance of five kilometers south of Thuamal Rampur. Sanatan is educated up to eighth standard in Oriya medium and has also worked as a teacher in a tribal welfare school. As chief of his community he is highly respected. He has fluency in both Manda and Oriya languages. The oral literature as dictated by Sanatan was documented by me in notebooks though some of the materials was also recorded on audio tapes with a cassette recorder. The transcribed data was thoroughly checked by the informant and the documented literature was read out to several groups of Manda speakers who have: approved it. The translation was undertaken in the initial stages, with the help of the interpreter, Konda Dora who knows both Oriya and Telugu. The process involved the following stages: 1) I read out the written Manda text from my notes; 2) Sanatan translated it into Oriya; 3) Dora interpreted it into Telugu, which I noted down and finally, 4) I translated the materials into English. Many complexities have crept in due to the several layers of translation, each contributing certain hurdles. Through intensive interaction with the Manda Kondhs, I attained a near native comprehension of the language and carried out my English translation by checking against the original Manda texts. However, it has not always been possible to find semantic equivalents in English for Manda socio-cultural practices recorded in the literature.

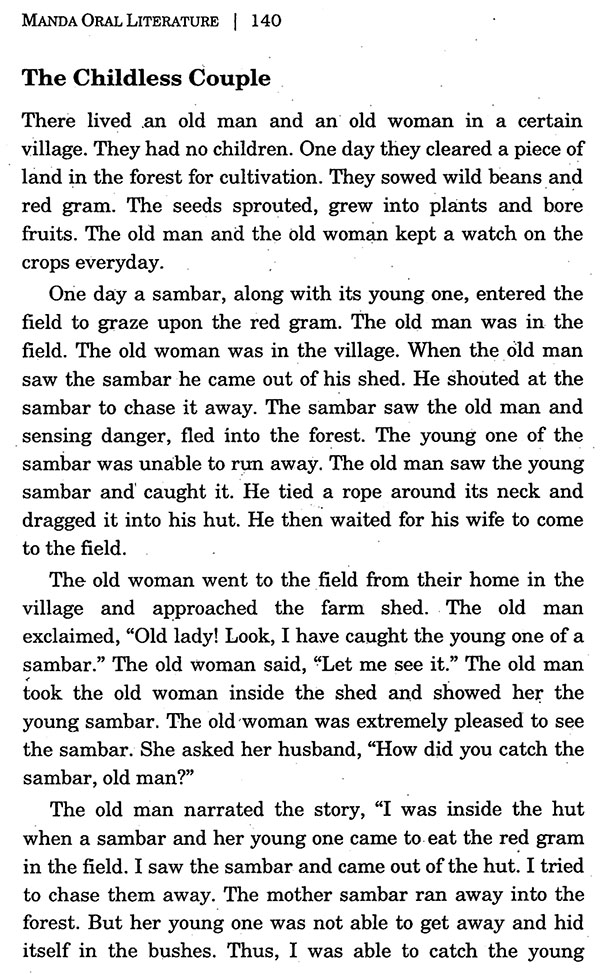

The oral literature assembled here reflects various dimensions of the Manda-Kondh community. This literature is a treasured depository of the tribal way of life and presents the community’s cultural heritage, world view, traditional wisdom, practical knowledge and philosophical life. Each narration represents various cultural aspects of the tribe, both material as well as spiritual. The mythology of creation deals with the origin of the earth, various deities, the Kondh people and their rituals and the duties of the sacred guardians in conducting the worship. There is a hierarchy of gods as well as rituals that have to be respected and followed strictly.

The Kondh community used to indulge in mariah, the human sacrifice made to the mother earth with a belief that the sacrifice would bring prosperity. But this practise was suppressed by the British officials in the middle of the 19% century and the sacrificial object was replaced by animals like buffalo, goat or ram. The festival is now known as Tuuki perbe and is celebrated in the month of puh or December-January. The ritual is portrayed in the narration. The festival of dulkun is a thanks giving ceremony to mother earth for bestowing people with a new harvest and is annually celebrated in November and December. The interaction between a poor boy and a celestial nymph forms the theme of another narration, depicting the tribe’s links with supernatural Bheema gods. Similarly, the life cycles of marriage, family life, interaction between man and animal, satire on the current judicial system and finally the apologues - all of these form an integral part of the oral literature of the Manda community.