About the Book RETHINKING EARLY MEDIEVAL INDIA This book changes the way we look at the history of early medieval India (c. 600-1300 CE). Raising questions about per iodization, it highlights the complex and multilinker nature of historical processes in the subcontinent. Apart from analysing the theoretical debates, the nature of political systems, and urban and rural economy and society, the volume also discusses gender, religion, art, language and ideas, thereby expanding the lens through which we view the history of pre-Sultanate and non-Sultanate early medieval India.

The thought-provoking essays, along with the incisive and critical Introduction, will interest students and teachers of ancient and medieval Indian history.

Preface This book emerged out of my long engagement with early medieval India, both as a historian and as a teacher. I began my innings in his-topical research with an epigraphic study of the rural economy of early medieval Bengal and Bihar for my MPhil, went on to study the inscriptions of Orissa for my PhD, and continued to engage with this exciting period in the course of my subsequent research and teaching at the undergraduate and postgraduate level. And yet, many years ago, when I was first approached by the Oxford University Press (OUP) to produce an edited volume on early medieval India, I confess that my initial reaction was not one of great enthusiasm. The reason was that in the course of my teaching, I had found that the history of early medieval India had in effect become a history of the his-choreography of the period. I did not want to produce yet another work which focused on the debate over whether early medieval India was feudal or not. In retrospect, I think that this is the reason why I delayed working on the book for many years. At some point, I realized that a volume on early medieval India could actually be a challenging venture if it sought to critically discuss the debate as well as the many important issues that lie beyond it. Once this was clear to me, selecting the essays and excerpts and writing the Introduction proved to be enjoyable tasks. During the course of working on this book, I benefitted greatly from discussions with many of my colleagues in the History Department of the University of Delhi-Seema Alavi, Sunil Kumar, Farhat Hasan, Raziuddin Aquila, Caravan Veluthat, Bhairabi P. Sahu, and Parul Pandya Dhar. I am especially grateful to Parul for helping out with glosses on technical terms related to art and dance. My friend Rukun Advani stepped in with very helpful advice at a critical juncture. K.P. Shankaran of the Philosophy Department of St Stephen's College was, as always, a source of thought-provoking ideas. My husband Vijay Tankha, as usual, pitched in with advice on many points, especially on stylistic issues. I would like to thank them all. I would especially like to thank the editorial team of the academic division, OUP, for their suggestions, support, trademark efficiency, and strict adherence to schedules, qualities I truly admire and appreciate. I am also grateful to the anonymous readers of the proposal at OUP for their useful comments and suggestions. A few words on the cover image: Parul Pandya Dhar introduced me to Chedha Tingsanchali's photograph of this sculpture of Ravana lifting mount Kailaga in the mandapa of the Virapaksa temple at Pattadakal, Karnataka. I owe thanks to Dr Gautama Sengupta, Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India; Mr Halakatti, Superintending Archaeologist, Archaeological Survey of India, Dharwad Circle; and to the photographer Some for making available a beautiful photograph of this sculpture. Aditya Arya, friend and photographic adviser, played an important role in ensuring the high quality of the photograph that was finally used. For me, the sculpture in question is much more than something that provides a striking visual for the cover of this book. Conceptualized and executed centuries ago by a brilliant anonymous sculptor, it is a symbol of the cultural creativity and vitality of the early medieval period.

Introduction A striking aspect of the history of the Indian subcontinent between c. 600 CE and 1300 CE, often referred to as the early medieval period, is that regardless of the theoretical framework invoked, regional and pan-Indian historical processes emerge with greater vividness and detail than in earlier centuries. Perspectives on this period are linked to larger issues such as the per iodization of India's past and the nature of Indian culture and civilization. They are also connected with how historians view the two major political events within which the early medieval is framed-the decline of the Gupta empire at one end and the consolidation of the Delhi Sultanate at the other. Periods between empires tend to be especially prone to neglect and portrayal as periods of decline.' The early medieval period was rescued from neglect many decades ago and became the subject of intense debate among historians, managing to shake off some of its image as a dark age along the way. And yet, it presents a classic case of historiography overwhelming history. At the end of a half century of debate, it is time to rethink the way we think about early medieval India.

The tripartite division of India's past into the Hindu, Muslim (or Mahtomedi/Mohammedan) and British periods is often seen as the invention and legacy of James Mill's History of British India (1817), but it was part of a much more pervasive perception among nineteenth century European scholars about India's past and present, one in which religion merged with other categories such as ethnicity, race, community and culture. The significant shift in the basis of the labels-from `Hindu' and 'Muslim' to 'British'-reflected an evolutionary perspective in which British rule marked a break that was qualitatively different from earlier ones, when centuries of backwardness and despotic rule, inextricably intertwined with religion, made way for enlightened governance. In this scheme of things, c. 600-1300, sliced through by the Ghaznavid invasions included the later part of the Hindu and the early part of the Muslim period. There were some more calibrated variations on the theme. For instance, writing in the early twentieth century, Vincent Smith divided India's past into five phases-the ancient period, Hindu period, the period of the medieval Hindu kingdoms, the Muslim period, and the British period, confidently asserting that these were self-evident divisions, not susceptible to any questioning.'

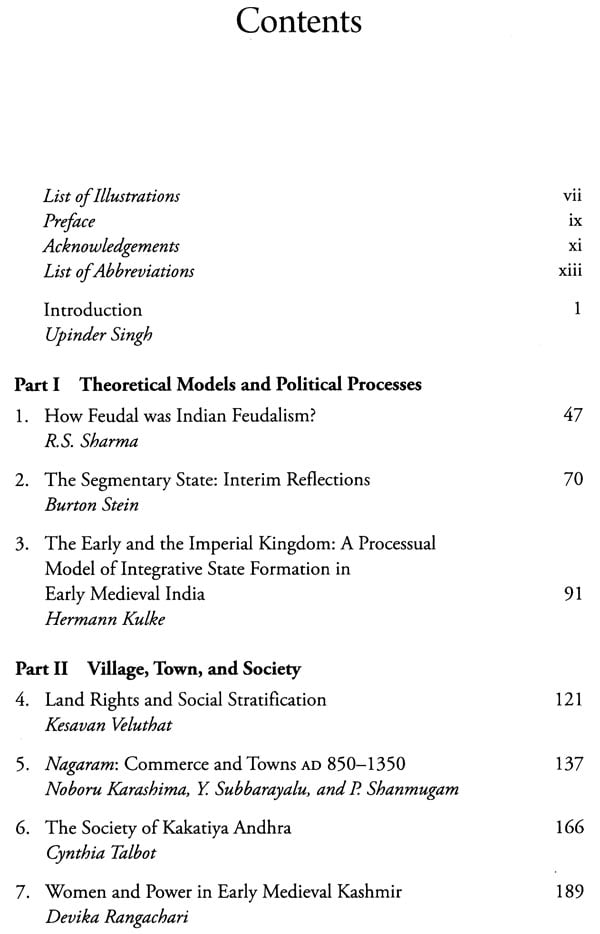

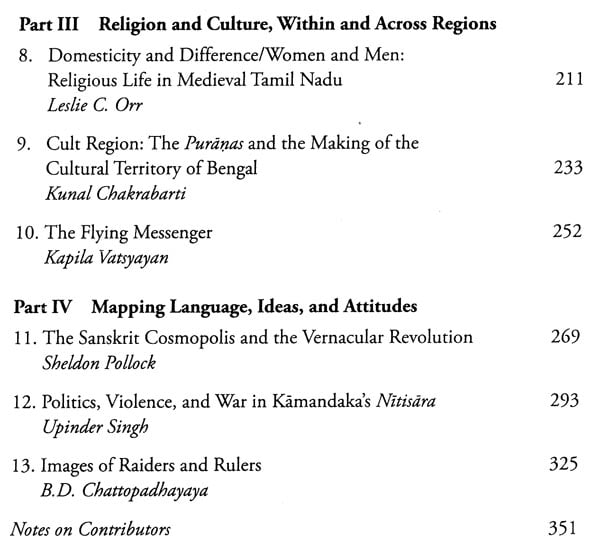

Book's Contents and Sample Pages