Vaisesika Sutra of Kanada (Sanskrit Text with Transliteration and English Translation)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAF255 |

| Author: | Debasish Chakrabarty |

| Publisher: | D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | Sanskrit Text with Transliteration and English Translation |

| Edition: | 2022 |

| ISBN: | 9788124602294 |

| Pages: | 128 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 200 gm |

Book Description

Kanadas Vaisesika Sutra,the textual basis for the Nyaya- Vaisesika system and the later Nyaya- Nyaya system, may be termed the earliest exposition on physics in Indian philosophy.It presented one of the earliest discussion on the idea of atomicity and on the true nature of knowledge as comprising the categories of dracya (substance), guna(attribute), karma (action),samanaya (generality),visesa (paricularity0 samaavaya (inherence ) and abhave (non-existence). This book presents the original Sanskrit text of the Vaisesika Sutra along with its Roman transliteration and a translation in the English language . The lucid transliteration is a scholarly attempt to retain the feel of the original sutras while conveying the intended meaning accurately words are added in the translated text for the benefit if syntax but they are placed in parenthesis. The translated text has sub- titles that aid in simplifying the arguments by grouping the sutras. Besides, foot note are provided to explain technical terms and concepts in the original Sanskrit.

The book, published under the shastra Group of centre of Linguistic and English at Jawaharlal Nehru University which had earlier brought out the Yogasutra of Patanjali, will prove useful to all researchers and students of ancient Indian Philosophy.

Debasish Chakrabarty coordinates the Science and Liberal Arts Department at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad. He is pursuing his doctoral research in Semiotics from the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

PHILOSOPHICAL enquiry, in India, began in the days of the earliest Upanisads. The Upanisads mark the epistemic shift from the Vedas and the Brahmanas in their focus on the notion of liberation of the soul.' The shift from the ritualistic to the more metaphysical form of enquiry found its takers in the various schools of philosophy that flourished around this period. The Upanisadic form of knowledge shifted its focus from the acceptance of the Vedas as revealed and controlled by rituals to knowledge as derivable from intuition, observation and analysis. The Upanisads were explorations in the search for enlightenment of the human condition and release from its bonds. Moving away from the mantra (verse) tradition, the Upanisads adopted the dialogue as their new form. The Upanisadic doctrines were concerned with the conceptualization of the other worlds, explorations of which would systematize the knowledge of the mundane world. It is in this milieu that the two classes of Indian philosophy, the theistic and the atheistic, came into being. While the atheists, namely the Buddhists, Jainas and Caravakas (materialists), sought to establish their own authority, the theists.' considered the Vedas as their infallible authority.

The earliest texts of these theistic philosophies were essentially cogent, classified and arranged records of the Vaise$ika-Satra of Kanada viewpoints of a particular system collated from oral discussions and speculations of the progenitors of these systems, assembled by them or their disciples. The texts were probably intended for people who were well versed in the oral tradition and thus could easily follow the import of the suggestive phrases, aphorisms and allusions to the view of rival schools and their refutations. According to Surendranath Dasgupta:

The fact that each system had to contend with other rival systems in order to hold its own has left its permanent mark upon all the philosophic literatures of India which are always written in the form of disputes .... At each step he [the author] supposes certain objections put forth against him, which he answers, and points out the defects of the objector or shows that the objection itself is ill founded.... Most often the objections of the rival schools are referred to in so brief a manner that those only who know the views can catch them."

Kanada's Vaisesika Sutra, our present concern, can be classified as a theistic text which does not believe in the existence of God and deals with physics and metaphysics. Tradition has it that major systems always look up to the basic text for the cardinal principles. The Yaiseeika Sutra happens to be one such text that forms the basis of the syncretic Nyaya-Vaisesika system that followed. To be accorded the status of a full-scale philosophical system, the concerns of the system ought to span a whole range: metaphysics, epistemology, ethics and theory of value, logic and philosophical method." Though the Vaise$ika Sutra provides the realist ontology, only when it is seen syncretically with the theistic, God-believing, Nyaya school (which provides the realist epistemology) can it be deemed a philosophical system. A philosophical system is also expected to develop its own metalanguage and reference mechanism whereby a tradition of commentary and expansion of its frontiers of knowledge are enabled. The syncretism Nyaya-Vaisesika system deals with each of these areas extensively. In the Yaisesika Sutra, Kanada develops a theory of atomicity, argues for a theory of sound and adapts an empiricist view of causality very much in the spirit of modern scientific enquiry.

A brief glimpse of the basic concepts of the Vaise$ika Sutra would enable the reader to gauge for herself the parameters within which this philosophical system functions.

The Vaisesika Sutra compartmentalises knowledge into seven (6+1) categories: dravya (substance), gUna (attribute), karma (action), samanya (generality), visesa (particularity), samavaya (inherence) and the late addition, abhava (non- existence).

A substance is the substratum of attributes and actions but is different from both. There are nine substances. Of these the first five, namely air, water, fire, earth, and ether are called the physical elements and all except ether, are composed of four kinds of atoms: air, water, fire, and earth. These atoms are indivisible and indestructible particles of matter and have the specific attributes of odour, taste, colour, touch and sound. The atoms are the indivisible part of a substance and are eternal and uncreated. According to Kanada, atoms are too small to be perceived but must be inferred from their effects. He goes on to say that they may be without attributes, albeit temporarily. Later writers have likened atoms to extension less mathematical points. Kanada seems to have thought that the eternal nature of atoms depended upon their imperceptibility, since perceptible entities are destructible. Ether, direction, and time are imperceptible substances, which are eternal and all pervasive. The mind is an eternal substance but is as small as an atom - the internal sense directly or indirectly concerned with all physical functions of the body like cognition, feeling, etc. The self is an eternal and all- pervading substance, which is the substratum of the phenomenon of consciousness. The individual self is perceived internally by the mind of the individual. The world is created of atoms, the composition and decomposition of which explain the origin and destruction of the composed objects of the world. Atoms cannot move by themselves, the source of their motion being unseen forces, which operate according to the law of action.

Attribute is that which exists in a substance and has no attribute or action in itself. It can exist only in a substance. There is no action in attributes. Action, like attribute, belongs to substance and is of five kinds."

A universal is the eternal essence common to all the individuals of a class. Particularity is the ground of ultimate differences of things. Ordinarily, we distinguish one thing from another by the peculiarities of its parts. Particularity stands for the individuality of the eternal entities of the world.

Inherence is a permanent or eternal relation by which a whole is in its parts, an attribute or an action is in a substance, the universal in the particulars and so on. The permanent relation between the universal and its individuals, and between attributes and actions and their substances is known as inherence. Finally, non-existence stands for all negative facts and is of four kinds."

Whether the Vaisesika Satra stands up to the scrutiny of 'a complete philosophical system', on its own, is debatable. Many scholars agree with Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan that,

The defect of the Vaisesika is that it does not piece together its results into a single coherently articulated structure. It is not a philosophy in the sense implied by the famous saying of the Republic that he who sees things together is the true dialectician or the philosopher. A catalogue of items is not a systematic philosophy. The many-sided context of human life is ignored by the V aisesika, and its physical philosophy and moral and religious values are not worked into a unified interpretation."

However, other scholars hold that the syncretic Nyaya- Vaisesika is 'a full-scale system' of Indian philosophy. Its contribution to all areas of philosophy is 'extensive' and is of 'fundamental importance'." In fact, the Navya-Nyaya or the Nee-logical school, founded by Cangesa Upadhyaya (about AD 1225) with his famous treatise, Taitoaciniamani, rose out of the ashes of the syncretic Nyaya-Vaisesika school. About these later developments, Dr. Radhakrishnan says,

The brief sutras (of Gautama and Kanada) set forth only the general and basic principles, epistemological and ontological, about things consistent with the viewpoint of the systems concerned. The other writers formulated their own views regarding the interpretation of the sutras and other questions without violating their allegiance to the sutras?

As regards the metaphysics of the system, Potter is of the opinion that the 'Nyaya- Vaisesika offers one of the most vigorous efforts at the construction of a substantialist, realist ontology that the world has ever seen'. The Vaisesika ontology admits repeatable properties and is realistic in nature, that is, it conceptualises the world as created from timeless entities, spatial points and temporal events. The epistemological debates on the idealist critique of the substance between the Nyaya-Vaisesika schools and the Buddhists are perhaps one of the most important confrontations in the history of Indian Philosophy. The Nyaya-Vaisesika system does not engage the disputations on ethical theory per se as it was not the primary focus of the system, yet the system does present arguments regarding issues such as belief in transmigration, karma and the possibilities of liberation. Though Vaisesika argues in accordance with the tenets of the system of logic, the torchbearer of the theory of philosophical debate in the Indian tradition is the Nyaya system. In fact, the system grew as one that specifically studied the theory of argumentation. It needs to be understood here that there was a peculiar system of division of labor that the ancient Indian seers formulated. Accordingly, the domains of inquiry of one school did not always overlap with the concerns of the others. So while the Mimamsakas dealt with ethical systems, logic and argumentation was the forte of the Naiyayikas. The question of philosophical method has been of interest to philosophers (Western and Eastern} for ages. The 'linguistic turn' has been hailed as a unique phenomenon in the history of philosophy." The concern with the theories of meaning, syntax, semantics and pragmatics has been a preoccupation with the Indian thinkers since long. Maybe that is the reason why the Vaiyakaranas (grammarians) are considered a philosophical school in themselves. The Nyaya system too looks critically at the empirical theories of validity and truth. The syncretism system opposes the uncritical use of intuition and appeals to revelation.

The Nyaya-Vaisesika theory of the world, through its atomic theory attempts to explain only the composite objects of the world that arenon-eternal. It certainly is one of the earliest theories in philosophy to look at the concept of atomicity, yet the Vaisesika Sutra certainly would not stand the scrutiny of the modern empirical understanding of atomic theory or atomic structure. Speaking pointedly about the atomic theory of the syncretic Nyaya~Vaise~ika system, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan says,

In its attempt to explain the origin and destruction of the world, it reduces all composite objects to the four kinds of atoms of earth, water, fire and air. So it is called the atomic theory of the world. But it is not a mechanistic or materialistic theory like atomism of Western science and philosophy. It does not ignore the moral and spiritual principles govern- ing the processes of composition and decomposition of atoms."

Date of the Vaisesika Sutra

The date of such an ancient text cannot be fixed with any certainty, though scholars are perfectly certain that the Vaisesika Sutra was written before Caraka's Suirasthana (AD 80). Scholars contend that the Yaisesiku Suira was written before the Nyiiya Sutra, which was known to Kautilya in some form of commentary in 300 Be. Certain scholars like Vidyabhusana think that Gautama (author of the Nyiiya Satra) flourished at around 555 BC, which would then place Kanada at around 600 Bc. Some Chinese scholars like Chi- Tsan date the Vaisesika Sutra at about 800 years before Buddha. In any case, scholars think that there is ample evidence to prove that the Vaise$ika Suira is pre-Buddhist and can be dated approximately between 600 BC to 200 Be.

The Text and the Author

Vaisesika, the name of the system, has been interpreted in two ways. One explanation is derived from the fifth category, uisesa, used in the sense of 'particularity'. Another view is that the name of the system is derived from the category oisesa, on which the conception of the atomic theory is based. In the latter case uisesa is interpreted as 'special'. Whatever be the point of view, tnsesa as a category is diametrically opposed to the category of siimiinya (universal). Vise$a is that underived peculiarity that explains the differences of partless eternal substances like space, time,Souls, minds and atoms of similar kind. Udayana, in Kiranavali, IS of the opinion that visesa is as imperceptible as the atom.

The founder of this school, probably a fictitious person, is popularly known as Kanada, the eater of lamas. The word kana, according to Sridhara, means grain, Kanada supposedly lived on grains picked up from the roadside. Or more appropriately, the word kana may mean atom; Kanada would then be an atom-eater, and that as the nickname of the founder of the system, would suggest his association with the atomic theory. According to the tradition preserved in the Buddhist writings, the name of the founder of the Vaisesika system was Uluka, and the system has also been known as Aulukya. It has been speculated that the name, Uluka or owl, was given to him because he worked during the day and scoured for his food at night. The Hindu philosophical tradition associates Kanad with Benaras and Gautama or Aksapada ('eyes in his feet ), the author of the Nyiiya Sutras, with Mithila. Both these places were influential seats of learning and many of the later torchbearers of the system hailed from these two centers.

| Acknowledgements | vii | |

| The Sastra Group at Jawaharlal nehru University -An Introduction | ix | |

| Prefatory Essay - Six Indian Philosophical Systems and Kanada's Vaisesikasutra | 1 | |

| Introduction | 21 | |

| General Overview | 21 | |

| Date of Vaisesika Sutra | 27 | |

| The Text and the Author | 27 | |

| Structure of the text | 28 | |

| Syncretism: The Vaisesika and Nyaya Philosophies | 29 | |

| Visesika and Purva-Mimamsa: Relations | 33 | |

| Nyaya-Vaisesika literature | 36 | |

| Vaisekia Sutra | ||

| 1 | First Chapter | 39 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

| 2 | Second Chapter | |

| First Ahnika | 49 | |

| Second Ahnika | ||

| 3 | Third Chapter | 61 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

| 4 | Fourth Chapter | 69 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

| 5 | Fifth Chapter | 74 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

| 6 | Sixth Chapter | 82 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

| 7 | Seventh Chapter | 88 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

| 8 | Eight Chapter | 97 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

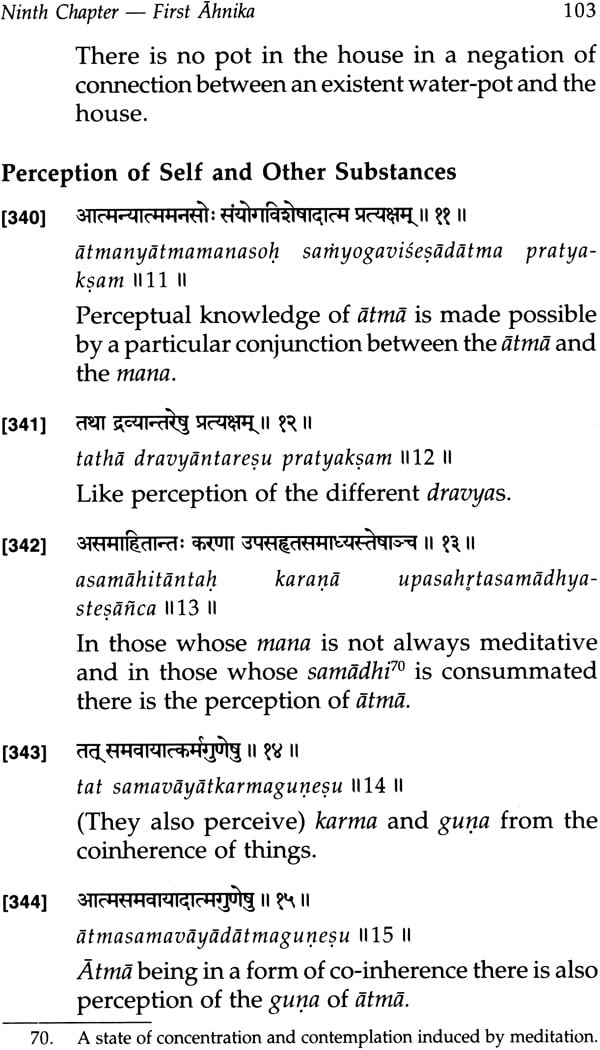

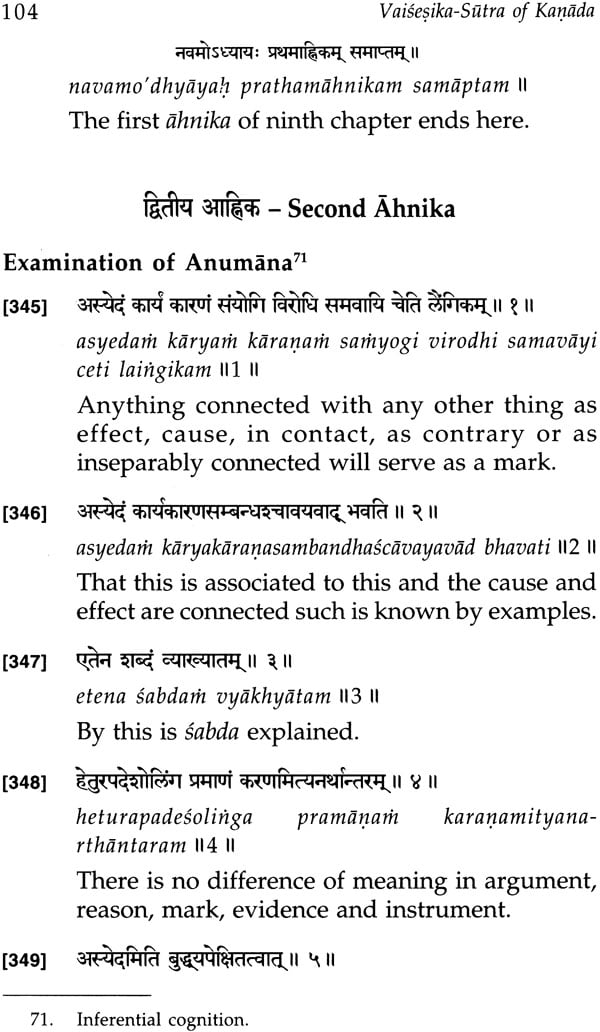

| 9 | Ninth Chapter | 101 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

| 10 | Tenth Chapter | 107 |

| First Ahnika | ||

| Second Ahnika | ||

| Bibilliography | 111 | |

| Index | 113 |