Adakatha The Story of Indian Advertising

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAU049 |

| Author: | Anand Halve and Anita Sarkar |

| Publisher: | Centrum Charitable Trust |

| Language: | ENGLISH |

| ISBN: | 9788192043210 |

| Pages: | 335 (Throughout Coloured Illustration) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 10.00 X 9.00 inch |

| Weight | 1.43 kg |

Book Description

It is an honour for me to write a foreword for this book on advertising and communications, a profession that has sold ideas and dreams to an evolving Indian consumer for decades.

My experience has principally been in commerce and the market, where millions of consumers have been persuaded to try out new products and ideas to improve their lives. Hence I will focus my foreword on the marketplace without which advertising would have neither a product nor a customer. As industry, marketing and the consumer have changed, so too have advertising methods. Such adaptation and flexibility have enhanced the consumer's unique experience of new offerings.

The century before Independence saw barely any growth in per capita income on the subcontinent. Population growth just about kept pace with the GDP. and the Indian market was an agglomeration of sub-markets. The movement of goods faced barriers of logistics, warehousing and local taxation. The word ‘consumption’ was not understood, let alone encouraged. And there were very few consumers to influence through advertising in spite of the large population. Often advertising merely meant informing a handful of the elite about the availability of a product.

During the 1930s, ghee consumers were persuaded to buy vanaspati, the most famous being Dalda. Former HLL chairman Prakash Tandon has described evocatively in his book, Punjabi Century, how the traditional wandering minstrels of Rajasthan were used to communicate the message of Dalda. A social anthropologist advised the use of pichwais to tell the Dalda story, wrapped into the Mahabharata or other epic stories. It marked the entry of sociologists and psychologists into marketing.

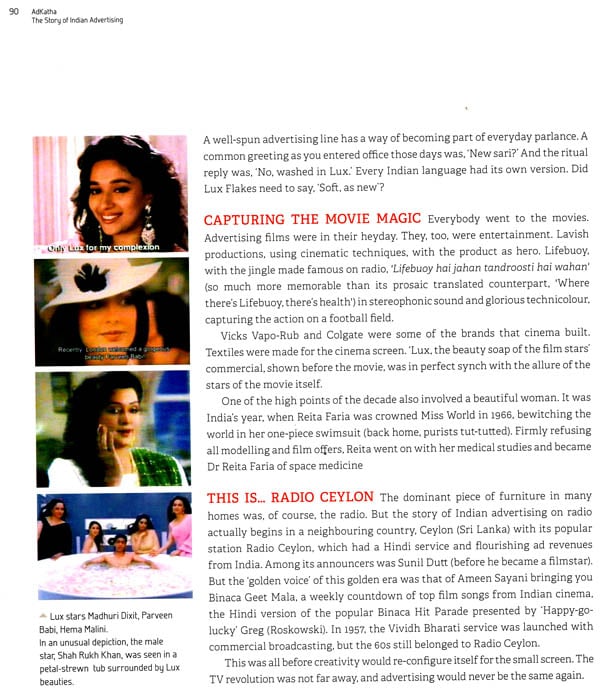

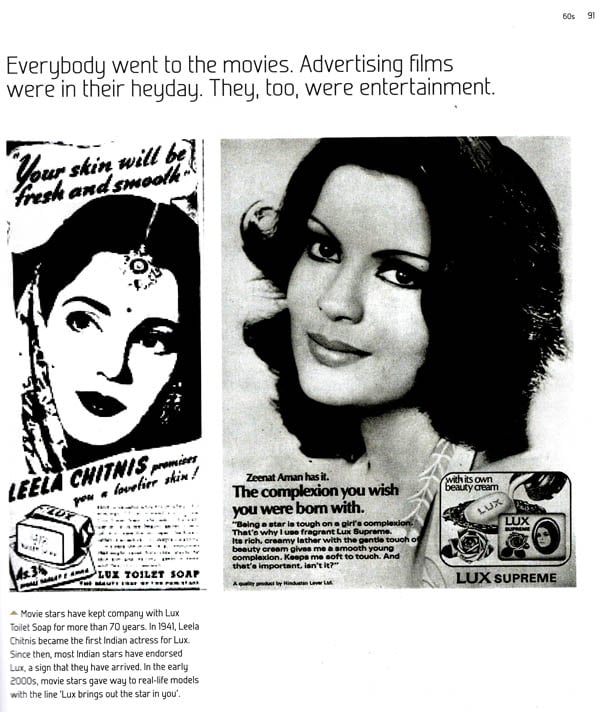

An early incident that influenced the Indian consumer was the appearance of Leela Chitnis as the first Indian model for Lux soap which, until 1941, had only featured JWT-contracted Hollywood models. The coy daughter of an English professor and wife of theatre personality Gajanand Chitnis, the young Leela would accompany her husband to the sets to earn a little by doing odd jobs. Her break came when the lead actress of Raja Harishchandra fell sick: Leela volunteered to do the role—and thus was born a star and the first Indian Lux model.

Indians are inveterate entrepreneurs, and have been so for centuries. Independence, however, dampened this entrepreneurial spirit rather than acting as a catalyst for it, thanks to a centrally planned economic orientation which promoted the distribution of what was already available over the manufacture of new products. Private enterprise was actively discouraged, although (luckily) not banned: Pandit Nehru openly stated that he did not like the word ‘profit’.

In 1951, the Nehru government banned the import of beauty aids in an effort to conserve valuable foreign" exchange. His distraught daughter, Indira, called Tata Director Kish Naoroji with the request that Tata consider manufacturing ladies’ cosmetics. The steel and electricity company was in a quandary, but only until Naval Tata saw, and was inspired by, a French opera by Delibes, Lakmé, set in British India, about the daughter of a Brahmin priest. Thus was born India's most famous indigenous cosmetics brand.

Packaging, transportation, warehousing, outdoor publicity, retail distribution, and cash collection methods constituted the fuel, fire, ladles and pans with which the advertising profession churned its convection currents within the pot. For example, until the 1950s, wooden boxes transported in railway wagons, were the standard for delivering soap and tea to markets. Progressively there occurred a huge innovation of using cardboard boxes and delivering through the nascent road system. This reduced costs and made handling much easier.

Marketers deployed sales and advertising vans that penetrated small towns and villages with products and feature films; they permitted the distributors a bank negotiation allowance to persuade a trader in a place with no bank to clear documents through a neighbouring area where there was one. Display and point of sale materials were used at a time when there were few mass media.

Business journalism was born in 1961 with the launch of The Economic Times, meant for a popular readership. Now both the Government and the newspaper frowned upon enterprise and wealth. Nobody in his right senses wanted to be counted among the wealthy. The public policy thrust on reaching out to the populace meant a rapid expansion of infrastructure -roads, post offices, banking services, electricity, transport- along with the ancillary superstructure of a nation in the making, such as newspapers, grocery shops, radio broadcasting and cinema theatres. However, although the per capita income of the average Indian grew in the 45 years after 1947, it grew very slowly, influenced by the ‘Hindu rate of economic growth’ and a gradual decline in population growth rate.

By the mid-1960s, a buoyant, independent India had ~ lost considerable self-confidence. It fought a bruising war with China. India was engaged with Pakistan in a second war in 1965. The Americans had stopped PL 480 wheat shipments, paving the way for Lal Bahadur Shastri's Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan, C Subramaniam’s green revolution, and Manoj Kumar’s film song, Mere desh ki dharti (Soil of My Land). The future looked uncertain, if not bleak. And I was ready to start my career. It is a middle class virtue to learn from adversity. And India started to learn.

In the mid-1960s, consumer goods companies were drafted to distribute a condom called Nirodh to shopkeepers who did not know what a condom was. In Tezpur, Assam, a young Hindustan Lever trainee tried to convince a trader to stock 10 cases by pointing to the market opportunity of the adjacent army station. The pragmatic trader replied with humour, "Bachhe, tumne tho mujhe moja de diya, magar yahan jootein kahan hain?" (You've given me socks, but where are the shoes?)

Consumer products were distributed by companies directly or through redistribution stockists. Sales people constantly ‘discovered’ new consumers in new village clusters requiring a cake of soap or a packet of tea. There was a highly visible press campaign by Brooke Bond in which chairman GVK Murthy addressed people as ‘bhai saheb’ and told them about the company’s unique distribution system, which ensured the freshness of Brooke Bond tea in the consumer's hands.