Albert Camus: Sense of The Sacred

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAT974 |

| Author: | Sharad Chandra |

| Publisher: | National Publishing House |

| Language: | ENGLISH |

| Edition: | 2016 |

| ISBN: | 9788121406625 |

| Pages: | 174 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 350 gm |

Book Description

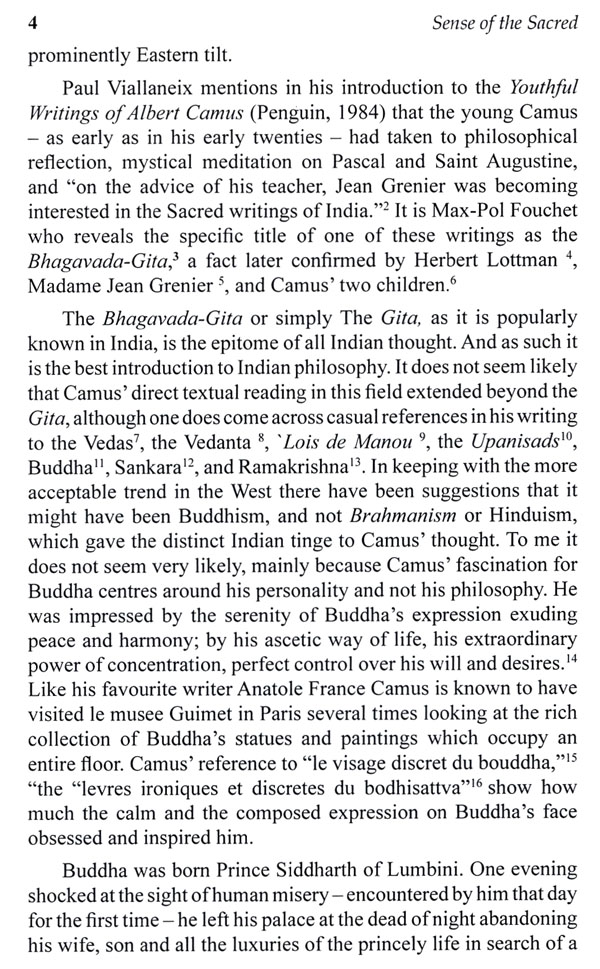

Asked by Jean-Claude Brisville to define what exactly he meant by "Secret of my universe: imagine God without the immortality of the soul' Camus explained, "I have a sense of the sacred and I don't believe in a future life, that's all." It is this sense of the sacred which closely affiliates him to the Indian thought and is the principal reason behind his continuing popularity in India. Camus condemned Christianity but was sacred at heart and had an incessant craving for unity. In this book distinguished by clarity and passion Shared Chandra first takes the readers to the core of the Indian thought and then to the source of this spiritual longing in Camus.

The theme of man's craving for truth, "le desir eperdu de clarte", "nostalgie", "hunger" for the absolute informs most of the writings of Camus. At barely twenty-three years of age he wrote, "Dieu a Dieu tel est son voyage". A few years later he pointed out inLe mythe de sisyphe that human life lacks meaning of "an appetite for clarity" and in 1947 he made an unequivocal statement in La peste that "man is made for totality" interestingly, expressing all along his serious doubts on the question of the existence and beneficence of God.

Undeniably an atheist, Camus has often being called a saint. He rejects the God he knew as being a hindrance to man's proper fulfillment in perfectly lucid self-consciousness. Shared Chandra amply illustrates in these pages how it is actually so and how Camus was a saint without religion, "a moralist of feeling", "conscience-keeper of his age", and how his attitude is not different from the Vedanta philosophy which bases itself on two simple propositions— that the human nature is divine, the jivatma and the paramatma are one and that the goal of human life is to realize this truth, since its non-realization is the root cause of human suffering.

Sharad Chandra is a Camus scholar and translator of his works into Hindi. She has written a number of books on Camus' proximity to the Indian thought some of the recent ones are, Albert Camus et L' Inde (editions indigene, France), Albert Camus and Indian Thought, Camus and India, The Higher Fidelity. Besides studies on Camus she has also published short fiction and poetry both, in English and in Hindi. Some of the recent titles are, Mutiny in the Ark, Concrete and Paper, Padari Mafi Mango, Ekanta mein Akele. Besides Camus she has also translated works by Atiq Rahimi, Amin Maalouf, Jean-Paul Sartre, Claude Simon, Michel Deon, Symbolist poets — Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Mallarme, Verlaine, and the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. A free-lance columnist she has been contributing regularly to Rencontre Avec L' Inde since 1988.

She is the recipient of a Grand Prix from L' academie francaise, Paris, Best Translator's Award from the Translators' Association, India, a Fellowship from the Harry Ransom Research Center, Texas, a couple of residencies at the CITL, Arles and at the Fundacion Gulbenkian, Lisbon.

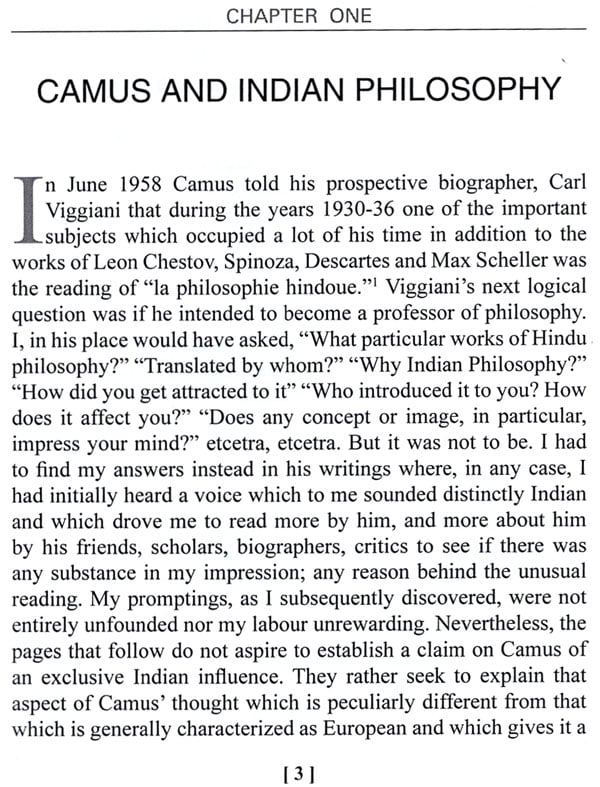

Vibrations of Indian thought in Camus' philosophy struck me many years back when I read L'Etranger or perhaps, an excerpt from it for the first time. I remember having taken up by it almost immediately. I read it again, looked for other writings by Camus, tried to learn about the environment in which he grew up, the books he had read, the people he had met making a note of those who had left an impressionable imprint on his mind—all, out of a simple, natural, literary curiosity not as part of a research project. But germination for a deeper, analytical study had sure set in. The affinity perceived by accident, with time kept getting deeper within me resulting eventually, in a number of books and academic papers on the subject.

In 1986 Aida Chevallier of Gallimard, visiting New Delhi for the World Book Fair nudged me over a cup of tea, "if you feel Camus' thought has that kind of proximity with the Indian philosophy why don't you translate him in Hindi?" That cast the die. Translating Camus brought me even closer. My first translation, Caligula appeared in 1987 and was steadily followed by most other works of Camus with the last one being the Hindi translation of Le Premier homme in 1996. Camus' plays are quite popular in India and keep getting staged regularly all over the country.

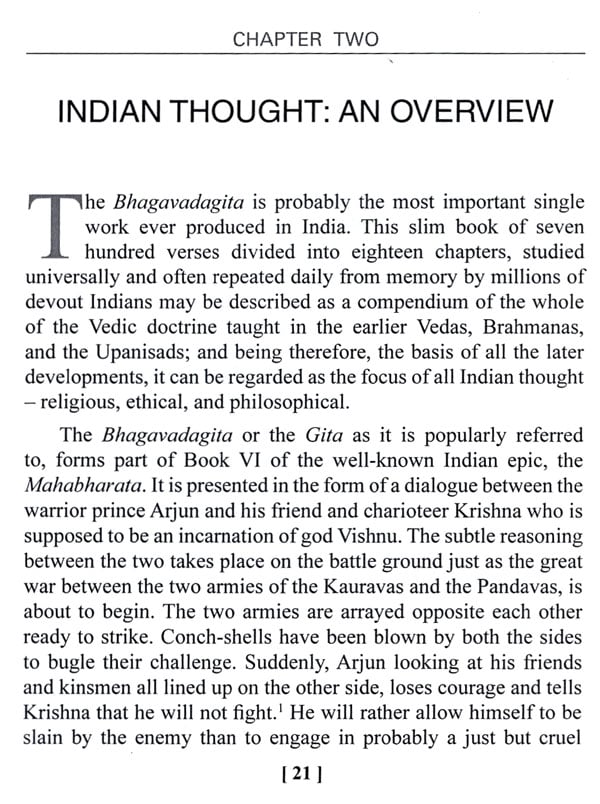

Three main ideas dominate Camus' thought—the absurdity of human condition, inevitability of death, and a constant, defiant search for happiness, first two notwithstanding. There is suffering, but "there are more things in men to admire than to despise". Camus' angle was always optimistic. He had an unflinching faith in man's ability "to create, all by himself, his own values". Life is absurd but revolt surpasses absurdity, and struggle leads to happiness. These concepts of absurdity, unintelligible suffering, death, as well as those of revolt and happiness are directly related to Indian thought. For, the Indian philosophy or Hinduism as it is popularly referred to in the West is not a historical religion like Christianity or Islam. It is a self-propelled, self-renovating, perennial system continuing forever the fundamental ideals conceived by the visionary thinkers out of their experience millions of years back.

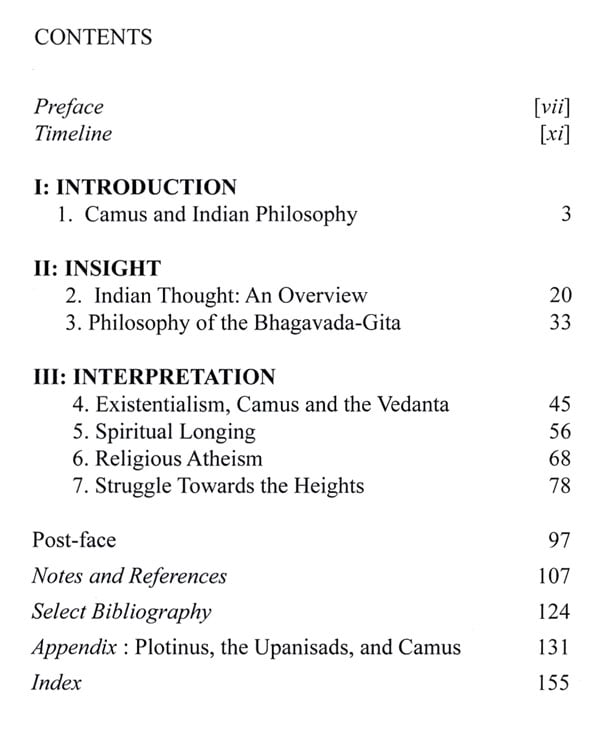

I have divided my book in three sections. Part one posits the subject; Part two provides an overview of the Indian philosophy spelling out briefly the basic concepts of its nine systems underlining the difference in their individual approaches. Part three systematically examines the premised analogy. They try to answer questions like, why was Camus' thinking so different from that of the other writers of his age, and at what juncture the Indian thought entered it—how, and to what extent.

Besides the ideological similarity between the Outsider and the Kathopanisad there are reiteration of ideas and concepts from the Gita in the Plague. Tarrou, the saint without God is a true `karmayogi' in the Gita terminology. He has a lucid mind and a compassionate heart. Camus' monk-like insistence on chastity, inner purity, a profound sense of the sacred, nostalgia for spiritual union, his reflections on truth, non-violence, religion and God ring a familiar bell in my mind. I have put my thoughts in the book. It is for the readers to judge how far I am correct.

Before concluding I would like to add that this study is not in the least a refutation, negation, or rebuttal of the views held by others. I have only tried to put forward the echoes of the Indian philosophy in Camus' writings as perceived by me. Right from his student days Camus was deeply concerned with the human condition and the closely related subject of human salvation. One can find strewn all over his work lyrical descriptions of the 'memory of the human soul' its destiny, man's desire, `nostalgie', for communion, totality with its source. This longing or quest is an essential aspect, rather the kernel of all Indian philosophy. This characteristic also features prominently in the Greek philosophy. Whether one borrowed from the other or if it was a parallel development is not my present concern. I have focussed primarily on the presence of this fact in Camus, and have given only a secondary thought to its possible source. It is the sacredness of Camus' outlook that first attracted me to him and continues to do so. The chapter, 'Plotinus, the Upanisads , and Camus' from one of my earlier books is annexed by way of providing supplementary information on the question of the Greek and the Indian philosophy in its relationship with Cams' thought. It is now generally established that there is an unmistakable trace of Indian philosophy in Cams' thought but its source, in the absence of the actual texts read by him, still remains inconclusive. My search continues.

**Contents and Sample Pages**