Alberuni's India

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAP550 |

| Author: | Dr. Edward C. Sachau |

| Publisher: | Rupa Publication Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9788171676408 |

| Pages: | 880 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 810 gm |

Book Description

In 1017 AD, at the behest of Sultan Muhmud of Persia, Alberani, aka Al-Birfini, travelled to India to learn about the Hindus, and discuss with them questions of religion, science, literature, and the very basis of their civilisation. He remained in India for thirteen years, studying and exploring these subjects. Alberfini's scholarly work has not been given the due recognition it deserves. Not for nearly eight hundred years would any other writer match Alberani's profound understanding of several aspects of Indian life.

About the Author

Dr Edward C. Sachau was a professor at the Royal University of Berlin, the principal of the Seminary for Oriental Languages, member of the Royal Academy of Berlin, corresponding member of the Imperial Academy of Vienna, honorary member of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and of the American Oriental Society, Cambridge, USA.

Preface

The literary history of the East represents the court of King Mahmtld at Ghazna, the leading monarch of Asiatic history between A.D. 997-1030, as having been a centre of literature, and of poetry in particular. There were four hundred poets chanting in his halls and gardens, at their head famous Unsuri, invested with the recently created dignity of a poet-laureate, who by his verdict opened the way to royal favour for rising talents; there was grand Firdausi composing his heroic epos by the special orders of the king, with many more kindred spirits. Unfortunately history knows very little of all this, save the fact that Persian poets flocked together in Ghazna, trying their kasidas on the king, his ministers and generals. History paints Mahmtld as a successful warrior, but ignores him as a Maecenas. With the sole exception of the lucubrations of bombastic Utbi, all contemporary records, the Makaincit of Abtl- Nasr Mishkani, the Tabakeit of his secretary Baihaki, the chronicles of Mulla Muhammad Qhaznavi, Mahrruld A, arrak, and others, have perished, or not yet come to light, and attempts at a literary history dating from a time 300-400 years ater, the so-called Tadhkiras, weigh very light in the scale of arter-of-fact examination, failing almost invariably whenever are applied to for information on some detail of ancient

Persian literature. However this may be, Unsure, the panegyrist, does not seem to have missed the sun of royal favour, whilst Firdausi, immortal Firdausi, had to fly in disguise to evade the doom of being trampled to death by elephants. Attracted by the rising fortune of the young emperor, he seems to have repaired to his court only a year after his enthronisation, i.e. A.D. 998. But when he had finished his Sheihntima, and found himself disappointed in his hopes for reward, he flung at him his famous satire, and fled into peace less exile (A.D. 1010)) In the case of the king versus the poet the king has lost. As long as Firdausi retains the place of honour accorded to him in the history of the world's mental achievements, the stigma will cling to the name of Mahmud, that he who hoarded up perhaps more worldly treasures than were ever hoarded up, did not know how to honour a poet destined for immortality.

And how did the author of this work, as remarkable among the prose compositions of the East as the Sheihncima in poetry, fare with the royal Maecenas of Ghazna? Alberuni, or, as his compatriots called him, Abu Raiban, was born A.D. 973, in the territory of modern Khiva, then called Khwarizm, or Chorasmia in antiquity.2 Early distinguishing himself in science and literature, he played a political part as councilor of the ruling prince of his native country of the Ma'muni family. The counsels he gave do not seem always to have suited the plans of King Mabmild at Ghazna, who was looking out for a pretext for interfering in the affairs of independent Khiva, although its rulers were his own near relatives. This pretext was furnished by a military emeute. Mabmild marched into the country, not without some fighting, established there one of his generals as provincial governor, and soon returned to Ghazna with much booty and a great part of the Khiva troops, together with the princes of the deposed family of Ma'miln and the leading men of the country as prisoners of war or as hostages. Among the last was Abil-Raihan Muhammad Ibu Ahmad Alberuni.

This happened in the spring and summer of A.D. 1017. The Chorasmian princes were sent to distant fortresses as prisoners of state, the Chorasmian soldiers were incorporated in Mahamild's Indian army; and Alberuni—what treatment did he experience at Ghazna? From the very outset it is not likely that both the king and his chancellor, Ahmad lbn Hasan Maimandi, should have accorded special favours to a man whom they knew to have been their political antagonist for years. The latter, the same man who had been the cause of the tragic catastrophe in the life of Firdausi, was in office under Mahmild from A.D. 1007-1025, and a second time under his son and successor, Mas'ild, from 1030-1033. There is nothing to tell us that Alberuni was ever in the service of the state or court in Ghazna. A friend of his and companion of his exile, the Christian philosopher and physician from Bagdad, Abulkhair Alkhammar, seems to have practised in Ghazna his medical profession. Alberuni probably enjoyed the reputation of a great munallim, i.e. astrologer-astronomer, and perhaps it was in this quality that he had relations to the court and its head, as Tycho de Brahe to the Emperor Rudolf. When writing the `IvStica, thirteen years after his involuntary immigration to Afghanistan, he was a master of astrology, both according to the Greek and the Hindu system, and indeed Eastern writers of later centuries seem to consider him as having been the court astrologer of King \lahmud. In a book written five hundred years later (v. Chrestomathie Persane, &c., par Ch. Schefer, Paris, 1883, i.p. 107 Df the Persian text), there is a story of a practical joke which Mahmfid played on Alberuni as an astrologer. Whether this be historic truth or a late invention, anyhow the story does not throw much light on the author's situation in a period of his life which is the most interesting to us , that one, namely, when he dommeneced to study India, Sanskrit and Sanskrit literature.

Table of contents

| Preface i | XI |

| Part i | |

| Preface | IV |

| On the hindus in general, as an introduction to our account of them. | 1 |

| On the belief of the hindus in god. | 11 |

| On the hindu belief as to created things, both "intelligibilia" and "sensibilia | 17 |

| From what cause action originates, and how the soul is connected with matter | 30 |

| On the state of the souls, and their migrations through the world in the metempsychosis | 35 |

| On the different worlds, and on the places of retribution in paradise and hell | 43 |

| On the nature of liberation from the world, and on the path leading thereto | 52 |

| On the different classes of created beings, and on their names | 73 |

| On the castes, called "colours" (yarn), and on the classes below them. | 83 |

| On the source of their religious and civil law, on prophets, and on the question whether single laws can be abrogated or not | 89 |

| About the beginning of idol-worship, and a description 95 of the individual idols. | 95 |

| On the veda, the puranas and other kinds of their national literature. | 109 |

| Their grammatical and metrical literature. | 120 |

| Hindu literature in the other sciences-astronomy, astrology, etc. | 138 |

| Notes on hindu metrology, intended to facilitate the understanding of all kinds of measurements which occur in this book. | 146 |

| Notes on the writing of the hindus, on their arithmetic and related subjects, and on certain strange manners and customs of theirs. | 157 |

| On hindu sciences which prey on the ignorance of people | 175 |

| Various notes on their country, their rivers, and their ocean -itinerabies of the distances between their several kingdoms and between the boundaries of their country | 184 |

| On the names of the planets, the signs of the zodiac, the lunar stations, and related subjects | 201 |

| On the brahmanda | 210 |

| Description on earth and heaven according to the religious views of the hindus, based upon their traditional literature | 217 |

| Traditions relating to the pole | 230 |

| On mount meru according to the belief of the authorsof the puranas and of others | 234 |

| Traditions of the puranas regarding each of the seven dvipas | 242 |

| On the rivers of india, their sources and courses | 248 |

| On the shape of heaven and earth according to the hindu astronomers | 255 |

| On the first two motions of the universe (that from east to west according to ancient astronomers, and the precession of the equinoxes) both according to the hindu astronomers and the authors of the puranas | 270 |

| On the definition of the ten directions | 281 |

| Definition of the inhabitable earth according to the hindus | 286 |

| On lanka, or the cupola of the earth | 297 |

| On that difference of various places which we call the 302 difference of longitude | 302 |

| On the notions of duration and time in general, and on 310 the creation of the world and its destruction. | 310 |

| On the various kinds of the day or nychthemeron, and on day and night in particular. | 318 |

| On the division of the nychthemeron into minor particles of time. | 325 |

| On the different kinds of months and years | 337 |

| On the four measures of time called mana | 345 |

| On the parts of the month and the year | 348 |

| On the various measures of time composed of davs, the life of brahman included. | 352 |

| On measures of time which are larger than the life of brahman. | 352 |

| On the samdhi, the interval between two periods of time, forming the connecting link between them. | 358 |

| Definition of the terms "kalpa" and "chaturyuga," and &n explication of the one by the other' | 362 |

| On the division of the chaturyuga into yugas, and the different opinions regarding the latter. | 366 |

| A description of the four yugas, and of all that is ejected to take place at the end of the fourth yuga. | 372 |

| On the manvantaras. | 380 |

| On the constellation of the great bear. | 383 |

| On narayana, his appearance at different times, and his names. | 390 |

| On vasudeva and the wars of the bharata. | 395 |

| An explanation of the measure of an akshauhini | 401 |

| Part ii | |

| A summary description of the eras | 403 |

| How many star-cycles there are both in a "kalpa" and in a "chaturyuga | 418 |

| An explanation of the terms "adhimasa," "unaratra, and the "aharganas," as representing different sums of days. | 424 |

| On the calculation of "ahargana" in general, that is, the resolution of years and months into days, and, vice versa, the composition of years and months out of days | 432 |

| On the ahargana, or the resolution of years into months, according to special rules which are adopted in the calendars for certain dates or moments of time. | 451 |

| On the computations of the mean places of the planets | 462 |

| on the order of the planets, their distances and sizes | 467 |

| On the stations of the moon | 486 |

| On the heliacal risings of the stars, and on the ceremonies and rites which the hindus practise at such a moment | 496 |

| How ebb and flow follow each other in the ocean | 507 |

| On the solar and lunar eclipse | 513 |

| On the parvan | 521 |

| On the dominants of the different measures of time in both religious and astronomical relations, and on connected subjects | 525 |

| On the sixty years-samvatsara, also called "shashtyabda." | 531 |

| On that which especially concerns the brahmans, and what they are obliged to do during their whole life | 539 |

| On the rites and customs which the other castes, besides the brahmans, practise during their lifetime. | 545 |

| On the sacrifices. | 548 |

| On pilgrimage and the visiting of sacred places. | 551 |

| On alms and how a man must spend what he earns | 557 |

| On what is allowed and forbidden in eating and drinking. | 559 |

| On matrimony, the menstrual courses, embryos, and childbed. | 562 |

| On lawsuits | 567 |

| On punishments and expiations | 570 |

| On inheritance, and what claim the deceased person has on it. | 573 |

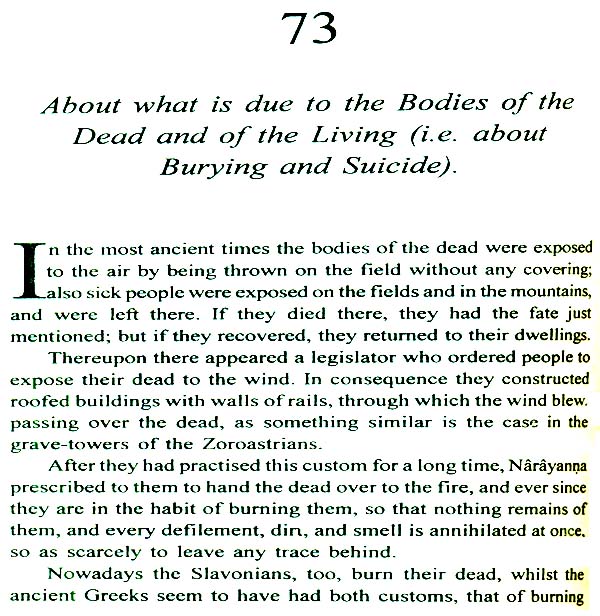

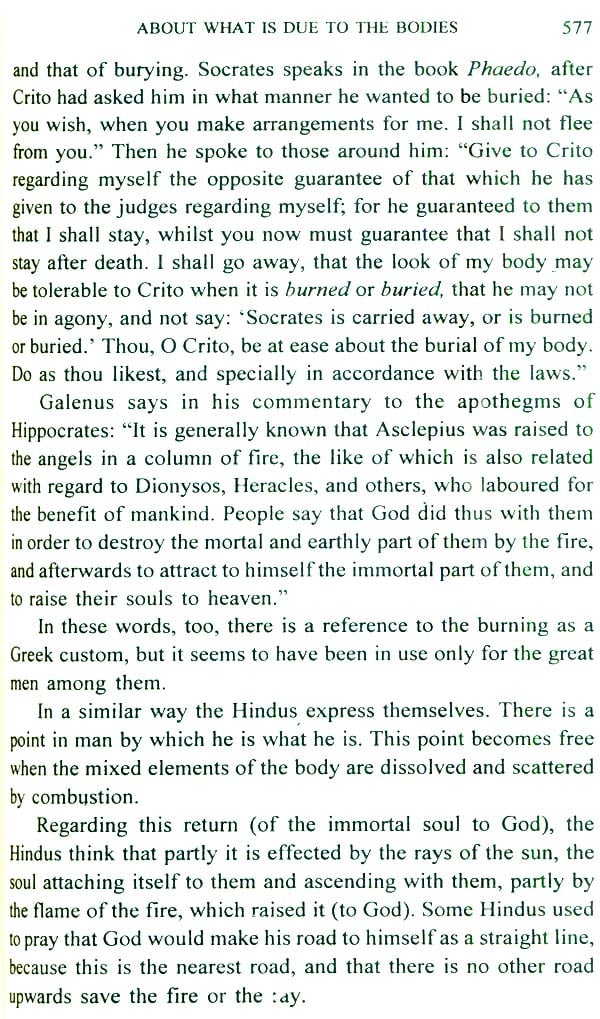

| About what is due to the bodies of the dead and of the living (that is, about burying and suicide) | 576 |

| On fasting, and the various kinds of it | 581 |

| On the determination of the fast-days | 584 |

| On the festivals and festive days | 588 |

| On days which are held in special veneration, on lucky and unlucky times, and on such times as are particularly favourable for acquiring in them bliss in heaven | 596 |

| On the karanas | 606 |

| On the yogas | 617 |

| On the introductory principles of hindu astrology, with a short description of their methods of astrological calculations | 625 |

| Annotations | 665 |

Sample Pages