Ancient India (Bulletin of the Archaeological Survey of India)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAL727 |

| Publisher: | Good Earth Publications, New Delhi |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2011 |

| Pages: | 420 (Throughout Color and B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.0 inch x 9.0 inch |

| Weight | 1.50 kg |

Book Description

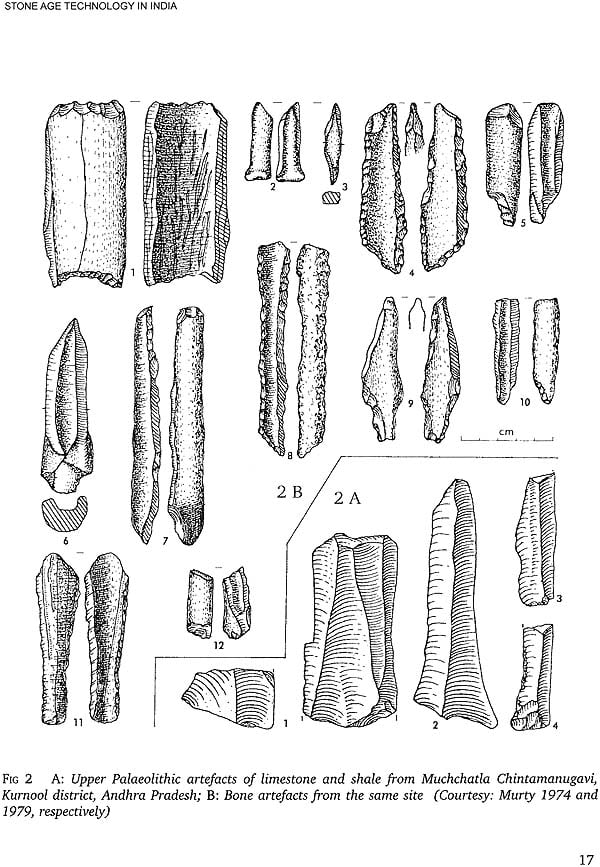

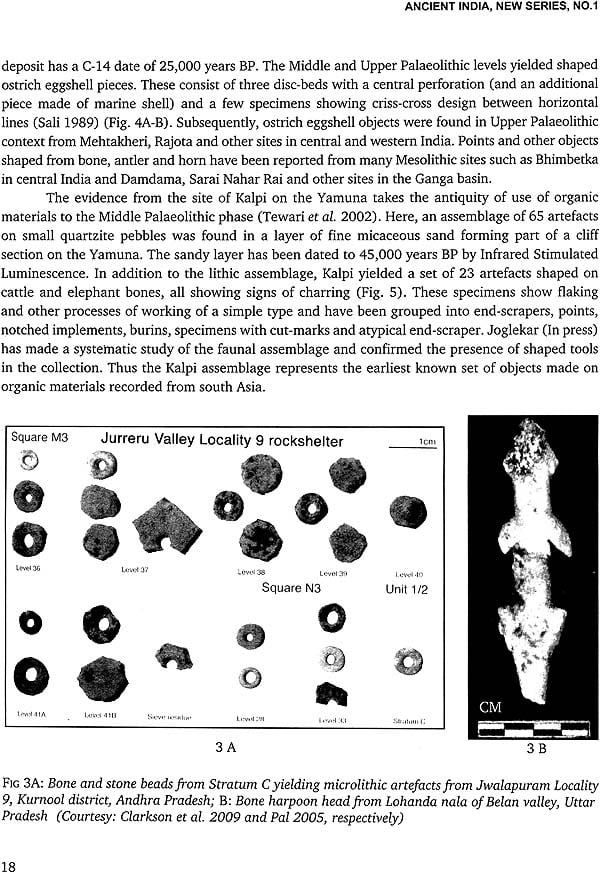

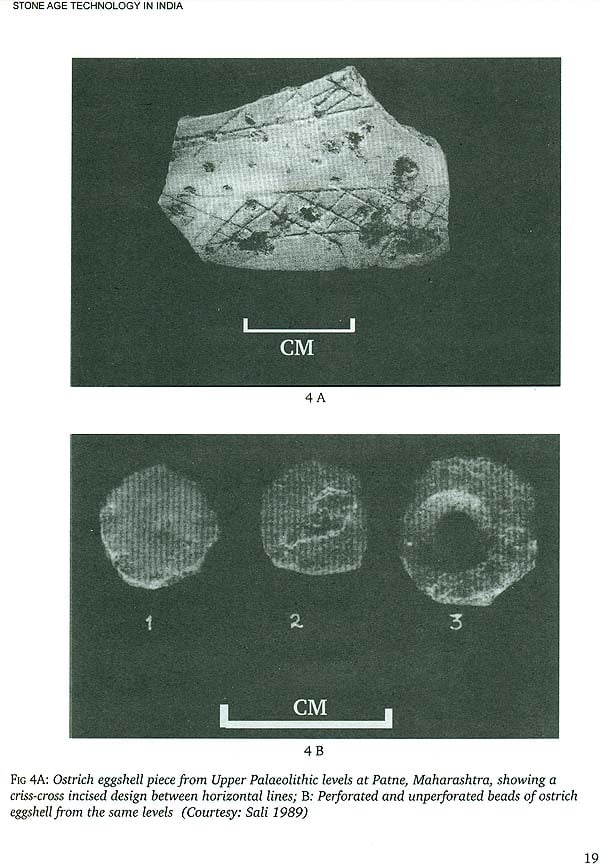

In this paper I propose to present a review of the evidence bearing upon certain aspects of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic technology in India. This topic was first dealt with by H. D. Sankalia more than forty years ago in his two well-known books titled Stone Age Tools: Their Techniques, Names and Probable Functions (1964) and Some Aspects of Prehistoric Technology in India (1970). These publications provided an excellent account of manufacturing techniques and types of stone implements of hunter-gatherer societies. In the present review, we will try to go one step further and attempt to relate technology to the functioning and evolution of Prehistoric societies. We are dealing with more than one- million-year-long pre-literate stage in which man led a nomadic and hunting-gathering way of life. The overwhelming body of evidence for reconstructing this long formative stage of the human story is formed by stone artefacts and, to a limited extent, by objects made of organic materials like wood, bone and antler. Let us start with one or two general remarks.

In the year 2006-2007, the birth centenaries of two students par excellence of India's ancient past were celebrated in the country - D. D. Kosambi and H. D. Sankalia. While they differed vastly in their overall approaches and methods, both Kosambi and Sankalia recognized the unique features of the country's heritage, its relevance to the present, and use of the present as a method to approach the past.

In the mid-60s of the last century they published their major books which are still widely used by scholars and students alike. Sankalia's book Prehistory and Protohistory in India and Pakistan appeared in 1963 (second edition in 1974). Two years later Kosambi's book The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline (1965) was published. Although as fresh students we were initially somewhat befuddled by the differing contents and approaches of these two books, we recognized that, far from being faced with the need to prefer one to exclusion of the other, both were indispensable sources to a meaningful understanding of our past. We soon realized to our pleasant surprise that while Sankalia's book was rich in carefully acquired and assorted data which is basic to all empirical sciences', Kosambi's work was replete with many carefully drawn lower and higher order inferences about the trajectory of the country's past. We grasped too the truth in the famous German philosopher Kant's statement that 'Thoughts without content are empty; intuitions (sense data) without thoughts are blind'.

The writings of D. D. Kosambi provide a good starting point for our review. As he has himself confessed, Kosambi lacked formal academic training in Indological studies and indeed arrived there from the 'roof. In fact, this was his advantage and we need several more 'roof- breakers'. Kosambi possessed an uncanny ability to recognize the woods among trees and made some very pertinent observations about the methods of Indological research and about Prehistoric life in general which no student of Indian prehistory can afford to ignore. Among these, I consider the following as the most important observations (Kosambi 1965: Ch. 2):

a) Ice Age was neither so harsh nor as extensive as in Europe, such that food-gathering, apart from hunting and fishing, was a much easier task and covered a wide range of edible items.

b) Culture is to be understood in the sense of ethnography; it refers to- the essential way of life of the people.

c) Food supplies are an essential basis of human cultures and are dependent on the means (techniques and instruments) adopted for procurement.

d) Any important advance in the means of production leads to population rise and alterations in relations of production.

e) Temporal variability exists in regional cultural development.

f) 'Living prehistory' or ethnography is an important component of the methodology of Prehistoric research.

Before relating these propositions to the available archaeological record of hunter-gatherer societies, let us briefly note the main stages in the development of Stone Age research in the country.

| Notes | 7 |

| Stone Age Technology in India | 9 |

| Palaeolithic India and Human Dispersal | 69 |

| From Stone Tools to Satellites: Recent Research | 87 |

| into the Prehistory of Tamil Nadu | |

| Prehistoric Rock Art Imagery of the Vindhyas, | 101 |

| Uttar Pradesh, India | |

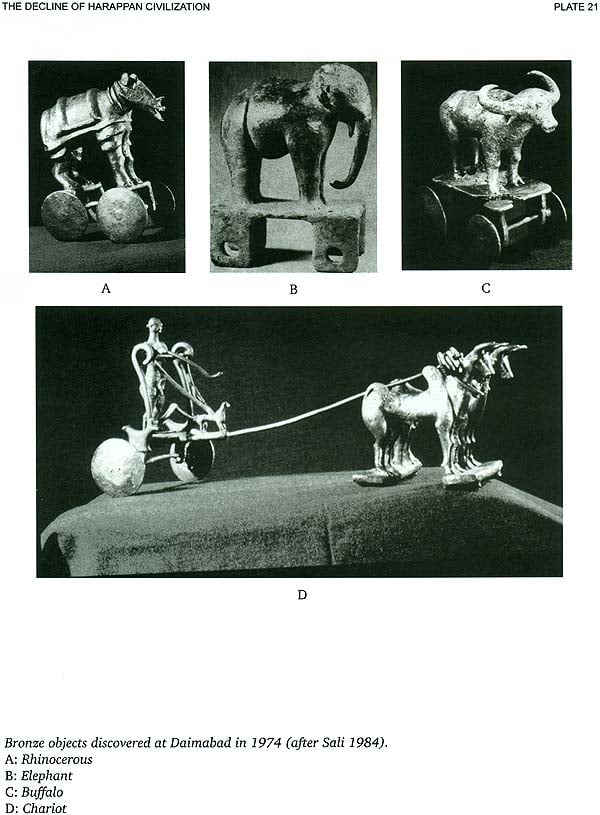

| The Decline of Harappan Civilization | 125 |

| Excavations at Karsola Kheda, Jind District, | 179 |

| Haryana, 2010-11 | |

| Excavations at Lathiya | 213 |

| (Ghazipur District, Uttar Pradesh): 2009-10 | |

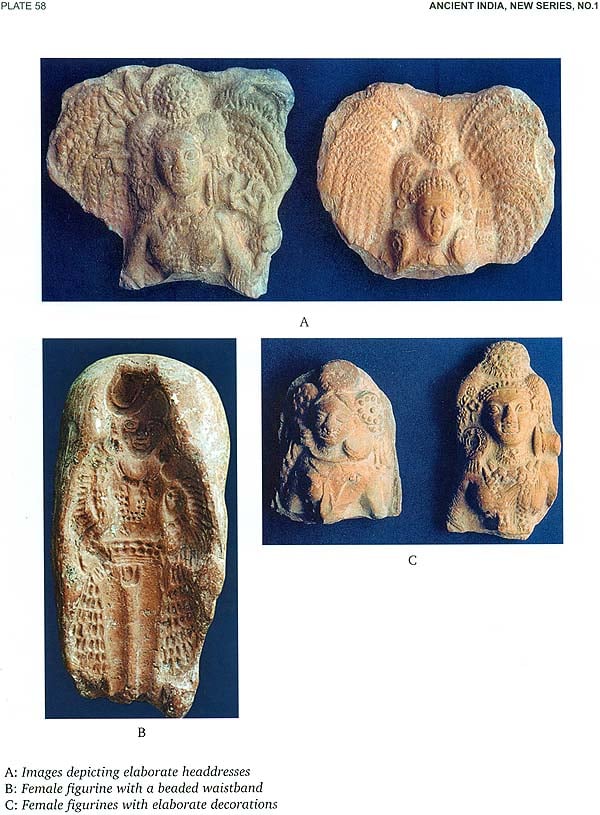

| Evolution of Terracotta Female Forms from Ropar | 233 |

| (from c. 200 Be to AD 600) | |

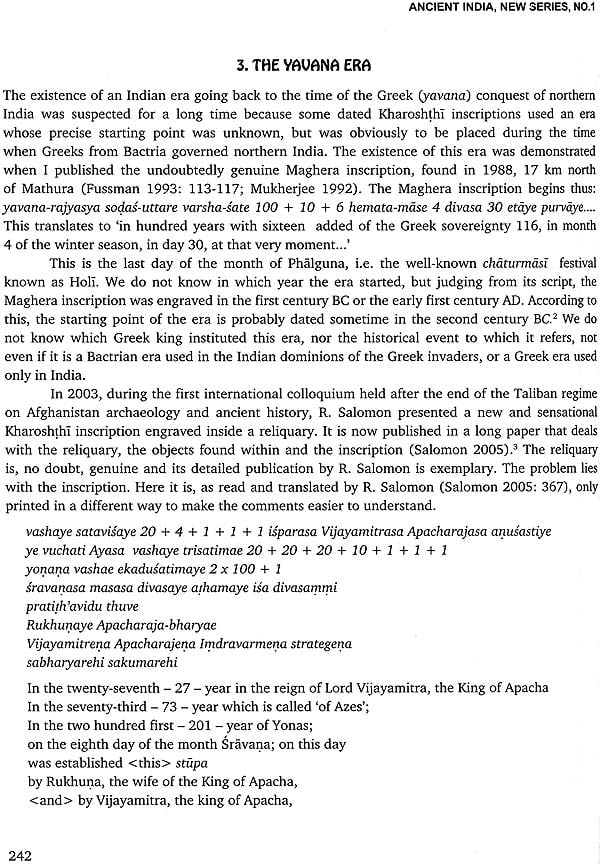

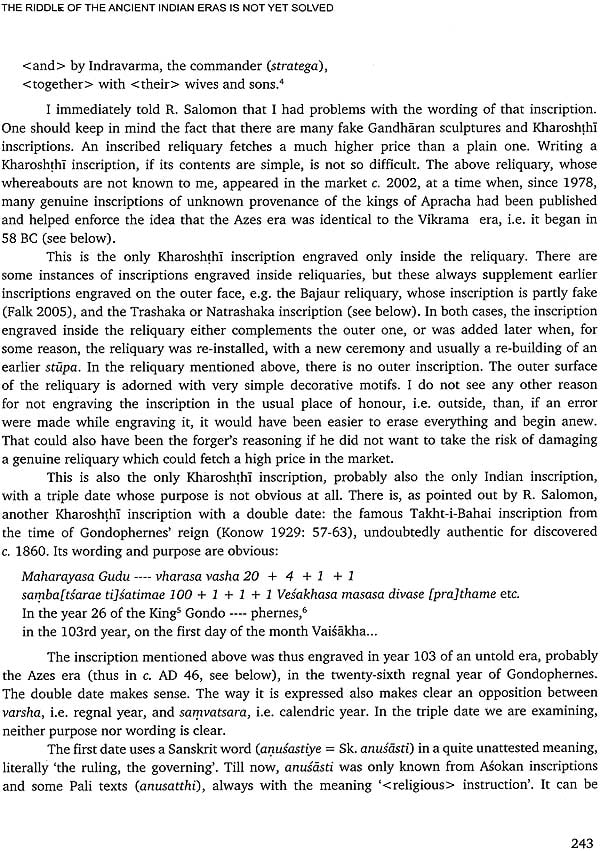

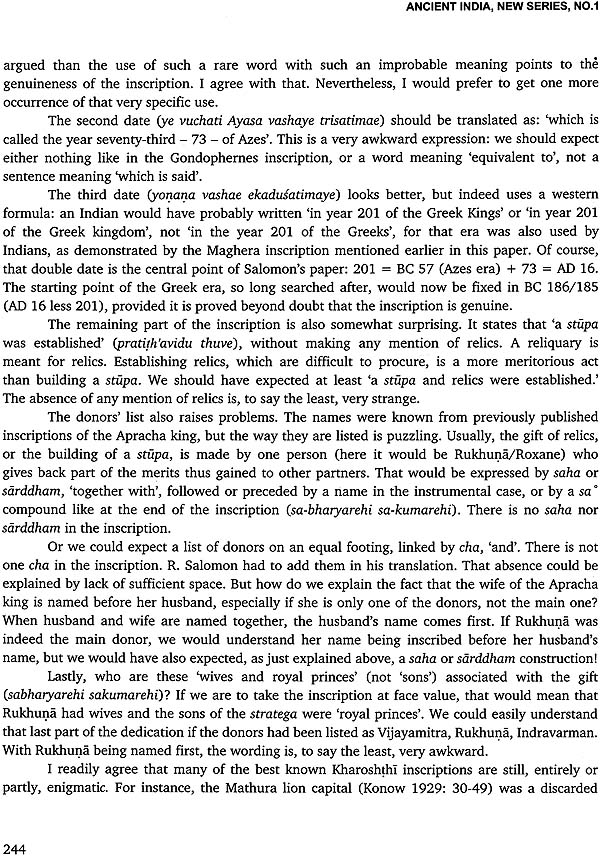

| The Riddle of the Ancient Indian Eras is Not Yet Solved | 239 |

| Six Decades of Indian Epigraphy (1950-2010): | 261 |

| Sanskrit and Dravidian Inscriptions | |

| Arabic and Persian Epigraphs: Recent Discoveries | 293 |

| Architecture and Society | 317 |

| Tribe, Tribal, and Indian Numismatics vis-a-vis | 337 |

| Neoevolutionary Paradigm | |

| Archaeology in North-East India: | 353 |

| The Post-Independence Scenario | |

| Museums in India: A Review | 369 |

| Royal Attributes of the Nirmanakaya Sakyamuni | 399 |

| and the Dharmakaya Buddhas | |

| Article Index | 411 |

| About the Authors | 415 |

| List of Plates | 418 |