Bagavather His Life and Times

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAP819 |

| Author: | Suresh Balakrishnan |

| Publisher: | A Birth Centenary Release |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2010 |

| Pages: | 704 (Throughout B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 800 gm |

Book Description

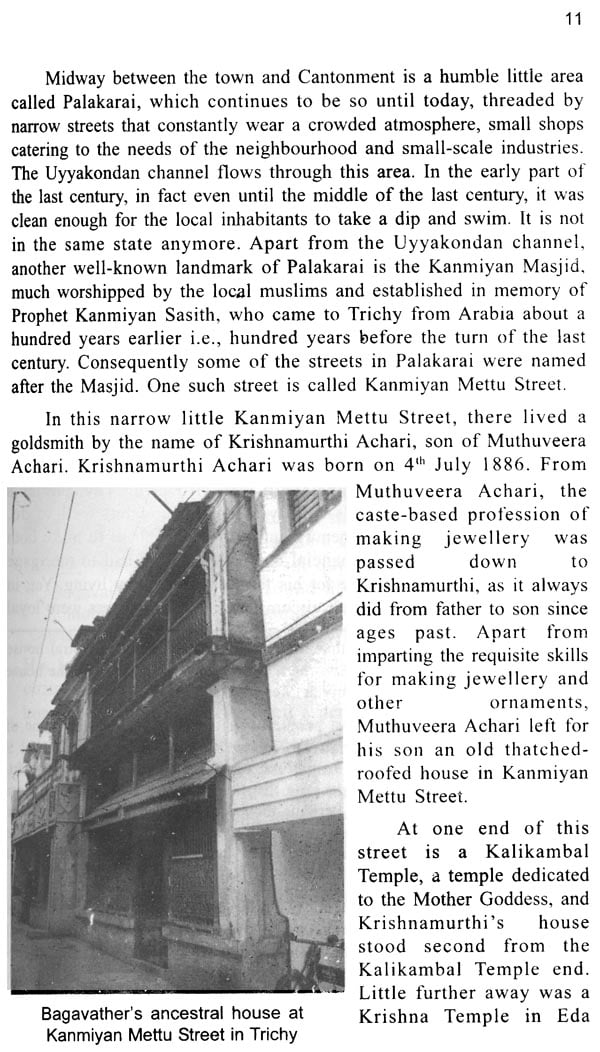

It has been said that every man is a volume, if you know how to read him. To encapsulate the life of a personality in a volume is at least the initial spur to writing a biography. The story of M K Thyagaraja Bagavather is the story of the rise and fall of the son of a poor goldsmith from Trichy. It is the story of a young boy who ran away from home because his father would not let him get carried away by music and drama. He was later found and grew up to become the biggeststar in Tamil cinema in his times. The story has much intrigue. Extraordinary singing ability combines with ascent from a humble social status to dazzling wealth, glamour, charisma, a charming personality and gifted voice and participation in multiple dimensions of art (including production of movies). Yet there is an unanticipated and abrupt fall from stardom and the slow decline of a man who had already become a cult- icon in his lifetime. The sad co-existence of fame and tragedy is such that a mention of his name invariably provokes the remark, "The way he lived and the way he lived". A broad outline of his life may be known to many already. "The result is that", as Somerset Maugham said in his Ten Novels And Their Authors about Tolstoy's War and Peace, "the quality of surprise, which makes you turn the pages of a book eager to know what is to happen next, is lacking; and, notwithstanding the tragic, dramatic and pathetic incidents which Tolstoy relates, you read with a certain impatience." Yet there is much in this book that, I can say with a fair amount of certainty, have not been compiled within two wrappers. And even the familiar elements lay scattered in various places. And this is the first book on him in English. I have striven hard to make my research as comprehensive as possible with reference to the material available in the many libraries I went. I have presented his life in a chronological sequence.

The entire exercise of writing this book consisted, for the most part, of putting together fragments of information that I managed to gather from multifarious sources in the course of my research. Consolidation and arrangement of the bits and pieces of information lying here and there had been the key task. And nuggets of information lay hidden in the most unexpected places.

There is sufficient material about his public life but very little that throws light on him as a son, husband, father and brother, the roles he played in his private life. The scarcity of information about M K T's personal life hinders light on how he acted in grief, anger, moments of vexation, exhaustion and so on. The only source about his personal life is his relatives but they have invested him in their memory with solemnity and sacredness. At this length of time there is little else I could do in trying to find more about his tempers or moods, his frailties and foibles as perceived in the personal sphere, in his roles as a member of his family and amongst his intimate circle of friends. I have not found any of his personal letters except perhaps one. His relatives say that he spent most of his time on his public activities and was hardly seen at home. The magazines I went through only substantiate that claim. A coherent and continuous narration of events from his personal life has not been possihle. But this book, I hope, presents him in all his dimensions as an artiste in much more detail than has ever been presented hitherto and through a coherent and chronological narration of events.

I hope I have used veracity and balance in the selection of material and have not concealed from the reader the criticisms and negative comments which magazines made about him at different times. "The ideal biographer should be a perfectly impartial man", wrote Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in his absorbing non-fiction' Through The Magic Door', "with a sympathetic mind, but a stem determination to tell the absolute truth". A biographer admires the personality whose life he writes and the element of hero-worship could tend to project the hero in brilliant glimpse and flawless and stainless perfection. But a biographer does a bad job if he does not use proportion and balance. But during the course of writing this book, I was constantly aware that my admiration for him might make me glorify him disproportionately. I hope I have done my best, despite the sympathy and adulation, to guard myself against exaggeration and lack of proportion in writing about him as an actor or singer or about his personal characteristics.

The efflux of time has caused the one problem that every belated attempt to record long gone times faces. Many of those who knew him personally, acted with him on stage and cinema, heard his concerts in his best years, some of his family members and relatives, and particularly those who knew him in his childhood and teenage days are dead. Had a book like this been attempted three or four decades back, much that is sorely needed today would have been easily available. Papanasam Sivan, for instance, would have given us a wealth of information, enough to form the subject matter of an entire book by itself, both about Bagavathar's film songs and concerts. Sivan and Alathur Brothers would have been the best sources to provide the finer details about M K T's command in camatic music. M K Govindaraja Bagavathar would have been the best source to recount his childhood and formative years. But that kind of extensive research was not done by anyone in those days and what is lost can never be found now.

In the name of writing not only on his life but also on the 'Times' in which he lived my first thoughts were to paint on a much larger canvas. But I later discovered that should I take that route, the research and writing would have to increase manifold and the book would not be ready by 2010, in which year his hundredth birthday falls on 1 st March. I have therefore confined the digressions, which are material not directly related to him, to sort of creating a 'period ambience' and sometimes to set the right backdrop before narrating certain events. I hope the material relating to the 'times' help create a broader picture and provide an evocative account of the past.

On the banks of the river of Time, the sad procession of human generations is marching slowly to the grave; in the quiet country of the Past, the march is ended, the tired wanderers rest, and all their weeping is hushed.

"The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there" said L P Hartley". Many years ago, there was the Madras Presidency and it was a different place. What today is one big Madras city, the capital of the south in those days, slowly grew to its present shape after the British started to get portions of it from different previous owners. The city of Madras was no more than a collection of small villages and there must have been a few hints here and there that would have helped a present day native of Chennai recognize his own city. Madras, as it was as far back as before the turn of the last century, would reveal to him one astonishing scene after the other. It would begin with the sudden flattening of the fabric of the city's landscape. All the tall buildings of today vanish and the roads suddenly appear broader, cleaner and quieter. People go about their lives in a rather unassuming sort of fashion. Between Mylapore and Mambalam, the psychological distance is much longer than it is today. The roads 'get pitch dark and scary in the nights and some of the densely crowded areas of today, are quiet and eerie, hardly inhabited by people, and thickly covered by a dense growth of trees and bushes. Some of the best-known and long-standing institutions and landmarks of today do not even exist as an idea. "The beach of Madras! What a splendid place it is!", observed B Rajam lyer while writing in The Prabudha Bharata, 1896-98, a collection of articles that were to be later published as the immensely popular Rambles In Vedanta, "The abode of cool and refreshing sea-breeze, commanding a prospect of vast illimitable ocean on the one side and the best and the most picturesque row of buildings which Madras can boast of on On History, Article contributed to The Independent Review, July 1904, the other side, together with as picturesque a part called Marina, the beach serves at once to fill a man with ecstasy who is fortunate enough to take a walk in the morning over it." The silence in the streets is only infrequently broken by the loud rumbling of the wheels and the galloping sound of the horse-driven carriages. Horses heaving their flanks, the driver bringing his whip down on them so that some Mylapore lawyer may not be late to Court, the animals rearing and slithering etc., must have been a common sight, so common that people would have walked alongside hardly noticing it. There were 'Madras Coach' and 'Bombay Coach', Phaeton, Landau, Landaulet and Dakart, besides the 'Velur Jutkas' and 'Rekla'. In Victorian Madras, there was also strict dress etiquette for riding out.

The last decade of the 19th century was important for the arrival of new inventions on the scene. In the year, 1894, there was an exhibition in Mount Road of a new vehicle, an amusing little contraption that could run without being pulled by a horse, which would become familiar to later generations as the motor car. A couple of decades later, the motor car would become increasingly preferred to the old broughams and phaetons. It is interesting to note how every time a new invention appears on the scene and shows the exit door to its predecessor, much annoyance is caused to people who are used to the old fashioned method and found it well suited to their predilections. To them, the new invention is nothing more than a disturbing intruder into the settled order of things. In one of his articles in Ananda Vikatan, in 1941, the well-known S V V recalls with fondness the "two-horse carriage days" and likens the ubiquitous "ugly" motor cars in 1941 to "piglets" running incessantly up and down the roads. "Where we used to hear the sweet sound of the horses' gallop", he writes, "our ears are deafened by the conch-like honking of the motor car shorn." But the derision does not stop there. He loathed this new vehicle so much that he reminds the reader, with his characteristic humour, that there is only one occasion, according to hindu rituals, when a person goes in a vehicle accompanied by the sound of a conch-shell! In 1894, the tram, which has now long been obsolete and outdated as a mode of transportation but still remains a fond memory among those who have seen it before it was discontinued in 1953, was yet to begin running. The tram would become the most popular form of transport, carrying people from all sections of the society.

**Contents and Sample Pages**