Buddhist Iconography in The National Museums of Tokyo And Kyoto

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG111 |

| Author: | A.K. Bhattacharyya |

| Publisher: | Indian Museum, Kolkata |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2006 |

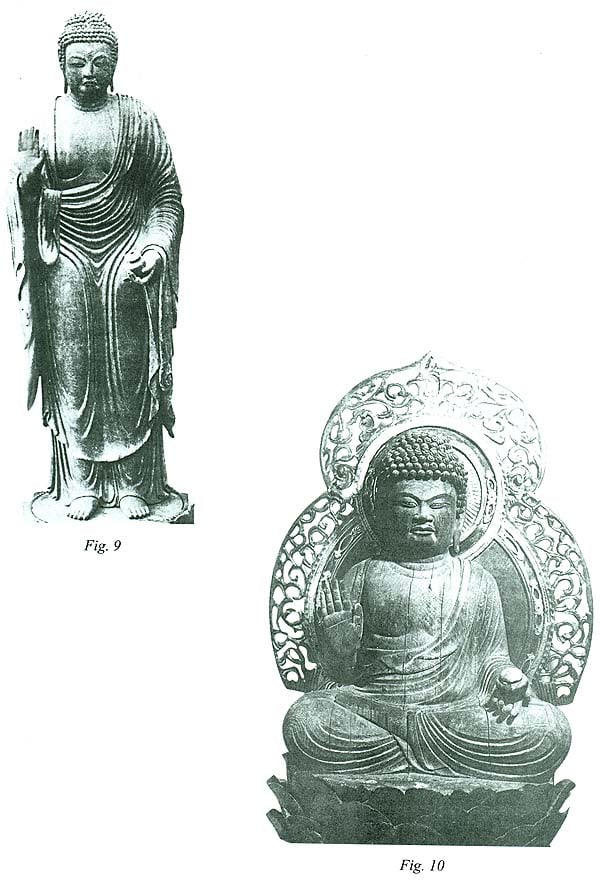

| Pages: | 72 (25 B/W and 30 Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.0 inch X 8.5 inch |

Book Description

Illustrations of Buddhist iconography are available in almost all published works on the collection of museums in countries professing Buddhism. These materials are important for study and research by scholars not only in those lands themselves but by others throughout the world. In these days of global intercommunication this has become more apparent. Yet the relevant collections are not easily available except by personal visit which, again, is not easy to undertake. Trade and commerce have grown globally, but exchange of scholars for obvious reasons have remained limited. In order to obviate difficulties such as these, one other way is to interchange publications on the necessary collections.

The present publication is a sincere effort in this direction specially on the category of objects relating to Buddhist iconography in the two major museums in Japan, the National Museums of Tokyo and Kyoto.

The specimens included here in both the cases cover not only those of Buddhist iconographical interest in the countries concerned but those from other parts of the world, as are collected and stored or exhibited in these institutions.

The treatment has been item with no order of chronology or any restriction to any medium of execution.

Professor A. K. Bhattacharyya, well-known for his accredited research publications in most fields of Indian and Trans –Indian art for the last more than fifty years, is the recipient of honours in his own country and abroad. He was awarded PRS of the Calcutta University, a Bengal Govt. Fellowship, a Fellowship from the Pacific Cultural Foundation and a Fellowship from the Japan Foundation, the Govt. of West Germany and Govt of Royal Thailand also awarding him Research Grants. Academically brilliant, he is an M.A. in Sanskrit and in Islamic History and Culture, both with a First Class, in the latter securing the first position.

Professionally qualified with a Diploma in Museology in London he served the two National Museums of India, the National Museum in New Delhi and the Indian Museum, Calcutta, the latter as its Director for more than a decade. Concurrently he was appointed Honorary Lecturer in Buddhist Iconography to teach in the Post-Graduate Department of Sanskrit at the Calcutta University.

His crowning glory was the award to him of the Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship for his distinctive contribution to the study and researches in art.

Professor Bhattacharyya is the author of more than twenty-two books, and contributed innumerable articles and Papers to Journals and International Conferences in which, in many cases, he was elected Sectional President.

In Japan, of the few National Museums, the Tokyo National Museum and the Kyoto National Museum stand out as containing the most important material relating to Buddhist iconography. Primarily because of this and secondly not to make the treatise unwieldy, it has been thought wise to deal with the material of the kind in a book of this character and dimension. The importance of such a treatment also lies in the fact that some of the specimens maintained in these museums, belong to temples distributed in different areas. In dealing with the collections in the museums, therefore, we will be dealing with some important items in the temples to which access is generally a hardship.

In discussing the material in these museums, it was thought useful to bring into consideration items elsewhere, often in distant source-lands, as comparison or as proto-types or even as varieties specially in mudras or hand-poses. The treatment has thus been akin to a research discussion more than a mere listing, with illustrations, of the museum-pieces.

Another important aspect of the endeavour such as this, is that the examples in the two National Museums are brought within the reach of researchers as well as the mere casual readers. This is particularly so when the country concerned is very far and not-so-easy-to-reach such as the islands of Japan.

It was during my several visits to Japan, in 1968,1973, 1976-77 and in 1980, that I had the rare opportunity of studying first-hand the sculptures and the paintings, and objects in other media, largely photographing these myself.

All the above considerations taken together, I set upon myself this project so that by inspiration collections on Buddhist iconography in all the important museums over the world may be known and studied by scholars in other parts in handy publications, without being brought over. In other words, this may serve as a mechanism of cultural exchange in a definite field not involving any hazards of transportation. I lay before the museums this proposition for active implementation wherever possible.

The collections in the two National museums include quite a number of examples that, while conforming to the prescriptions of the Sadhanas that form the basic for Mahayana, assimilated traits either from India or China, often revealing Japanese folk elements. The result has been a presentation of mixed types individually considered. Of the very important and interesting examples in various media, only those that are based on stone, drawings on silk, and embroidered on textiles, are selected here leaving out the others, the non-Buddhist art-objects, or those that have no iconographic features

I record here my hearth and obligatory thanks and acknowledgements to the authorities of the two National Museums of Japan, wherefrom the materials are here discussed, for the ungrudging facility offered to me to study their precious holdings reproducing them in the treatise.

I am glad to note here the over-all help rendered by my daughter, Smt. Chitra Bhattacharyya, M.A., in making the ms. Press-ready.

It is my great pleasure in recording my thanks for the overwhelming enthusiasm with which the present Director of the Indian Museum, Dr. Shaktikali Basu, agreed to include this treatise in the museum’s Monograph series. My hearty thanks are also due to Dr. Jaya Bhattacharya, Deputy Director of the Museum, who most devotedly and meticulously has seen the publication through the Press. Last but not the least, I greatly appreciate the care and promptness with which the Pritonia carried out the printing of the work, in which Sri Pinaki Datta, proprietor, put an exemplary effort. Sri Datta deserves my hearty thanks.

Buddhist iconography in Japan is almost co-eval with the introduction of Buddhism in that country. One of the earliest Buddha images in Japan belongs to the Asuka period, c. 600 A.D., the official introduction of Buddhism, according to accepted tradition, being in 538 A.D. The iconic forms were dictated from two sources, from China in the examples in the Wei period there, on the one hand and Greco-Roman proto-types from India on the other. Towards the last phase of Hinayana Buddhism in Japan, when all Buddhist worship centred round the Buddha, a terracotta wall-relief excavated at the ruins of the Golden Hall, Yamada dera, Yamada, Nara Prefecture, datable 2nd half of 7th century, shows the Buddha seated in dhyana mudra on a large petalled lotus in a pose that recalls figures of Amitabha, the Dhyani Buddha, in meditation. It represents, in all respects, the Indian character of Buddha figures of the Gupta idiom. The inter-communication between India and China continued in the following centuries, and in the eighth century, a great scholar-priest from India, made a perilous journey to China during the T’ang period-the period of her highest pitch of glory. He was Bodhisena Bharadvaja who later crossed over to Japan. While coming to Japan, he was accompanied by a Chinese priest and another from Vietnam. This visit is datable in the 13th December, in the year 18th of K’ai Yuan era within the T’ang period. His erudition and rare ability to recite the Hua-yen i.e., Gandavyuha Sutra were greatly appreciated in Japan, and his epitaph wishing to set up Buddha images, was religiously followed after his death. Bodhisena received singular honour from Emperor Shomu of Japan and he was made the Chief Priest in the inaugural ceremony of the installation of Daibutsu Birushana (The Great Buddha Vairocana).

Between 804 A.D. another Indian monk-scholar, Prajna, was present in China under whom the famous Japanese Saint-monk, Kukai (774-835 A.D.), better known by his posthumous honorific, Kobo Daishi, studied Sanskrit while he was on visit for study in that country. About two centuries later, in the 10th century A.D. there is evidence in a lithic record of the visit of a Chinese Priest, Chih-yi, to Bodh-Gaya and donating 3000,000 Scrolls of the Maitreya Sutra, praying to be re-born in the Paradise of Maitreya. He got a sculpture of Seven Mortal Buddhas and Maitreya Bodhisattva, made for installation at Bodh-Gaya. The sculpture bearing the record is now in the collection of the Indian Museum, Calcutta.

However, the first official contact of Buddhist with the Japanese Court can be traced much earlier, in 552 A.D., through South-West Korea when a Paekche king of that region sent some gifts to the contemporary Japanese monarch, Kimmei (540-571 A.D.). The Korean gifts consisted of Buddhist articles presumably some being of iconographic interest. Though this early Korean, or rather Buddhist, contact apparently did not touch the Japanese life of the common people, the official recognition by the royalty embracing the religion greatly paved the way as when Yomei, a succeeding Emperor of the Island Kingdom converted himself to that faith. Even at this, Buddhism did not take a firm root in Japan. In the meantime, for a period, there was clannish conflict between the two powerful groups, the Buddhist Soga and the anti-Buddhist Mononobe. The result of this conflict saw, however, victory for the Soga to which Yomei belonged. The Soga being now in the ascendance and a clan supporting Buddhism, had in the succession line of the clan, a Prince, Prince Shotoku, who was appointed Vice-regent and Heir-apparent. Prince Shotoku, a Jogu, allied himself with the Soga. Determined to put Buddhism on a strong footing, Shotoku penetrated into a non-Buddhist territory, Naniwa, and built the first temple there, the Shitenno-ji (Lit. the Four-good Temple). Of the numerous temples attributed to Shotoku, at least three deserve mention, namely, Koryu-ji in Kyoto, Horyu-Ji in Ikaraga and Tachibanadera in Asuka.

Even after its imperial patronage, Buddhism continued to be the central issue in clan rivalry. With humane approach and application, Buddhism remained a winning force; its doctrine of brotherhood through the establishment of Sangha had a wide acceptance with the masses and its principle of compassion shown towards the amelioration of the dreadful facts of human existence appealed to the afflicted with no reservations. Thus while Shinto totally turned its face against death, disease and disability, Buddhism stretched its hand out to ameliorate these sufferings with its chants, by having resource to the theory of karma and by holding out that death is nothing but a gateway to moksa or liberation from worldly bondage. In fact, Buddhism tried to convince man about the root of all these miseries and the ways to cut off them all in this life itself. The approach of Buddhisms was pragmatic and realistic, while Shintoism only pointed to ‘medical gods’ or ‘Spirits’ for a rescue. Historically, the early Buddhist monks brought with them the Chinese system of medicines to Japan which, thus, looked at the immediate and not the ultimate. While the Shinto method relied more on incantations and exorcism, the Buddhist were steeped in the spiritual doctrines of compassion, with a spiritual way for a total eradication of the sufferings. The result was that the Buddha, the personified compassion, appeared under these circumstances, as a great healer. He has been conceived as Bhaisajyaguru (Yakushi in Japan) with a bowl of medicine in hand. This satisfied both the longing to visualize a physician and the spiritual teacher to teach the ultimate way for healing all sufferings. Buddhism was thus accepted as the best form to adopt as a religion, for mainly being spiritually sound and formally most visible. The latter aspect was presented quite effectively by the Mahayana form of Buddhism that had already gained ground in India and China wherefrom Japan drew the inspiration.

| Introduction | 1-2 |

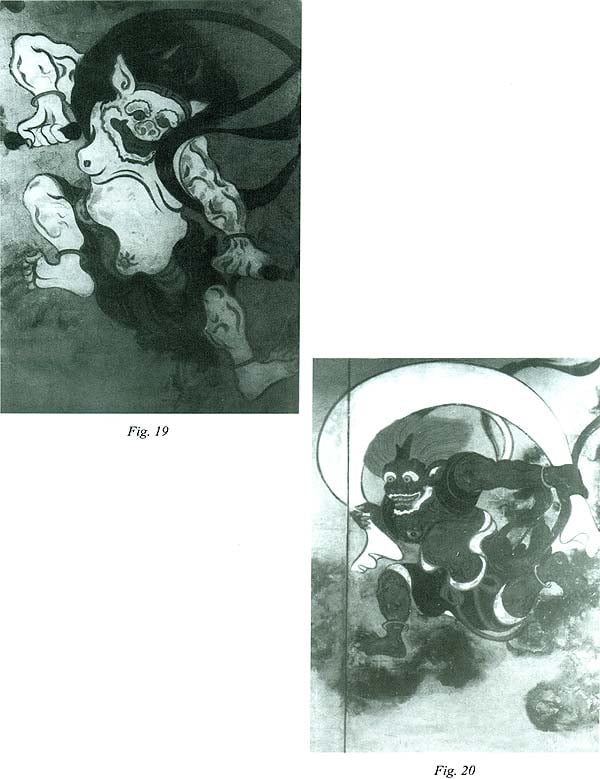

| Tokyo Museum | 3-19 |

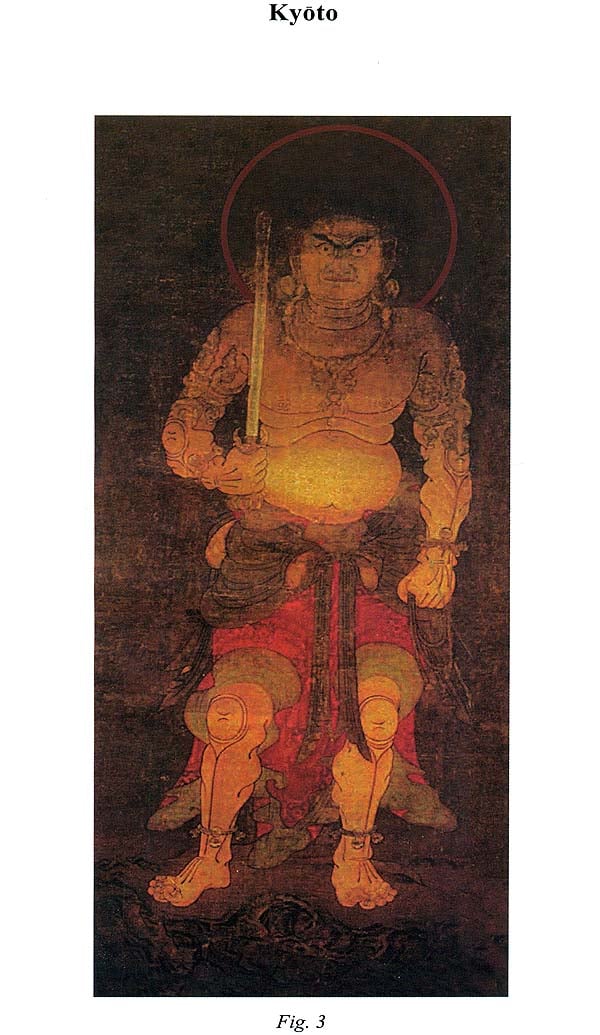

| Kyoto Museum | 21-39 |

| Bibliography | 40-41 |

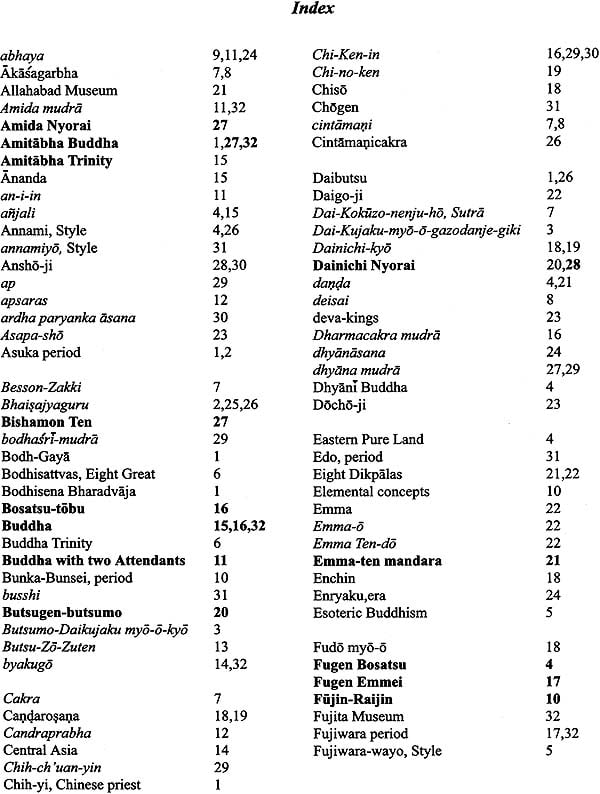

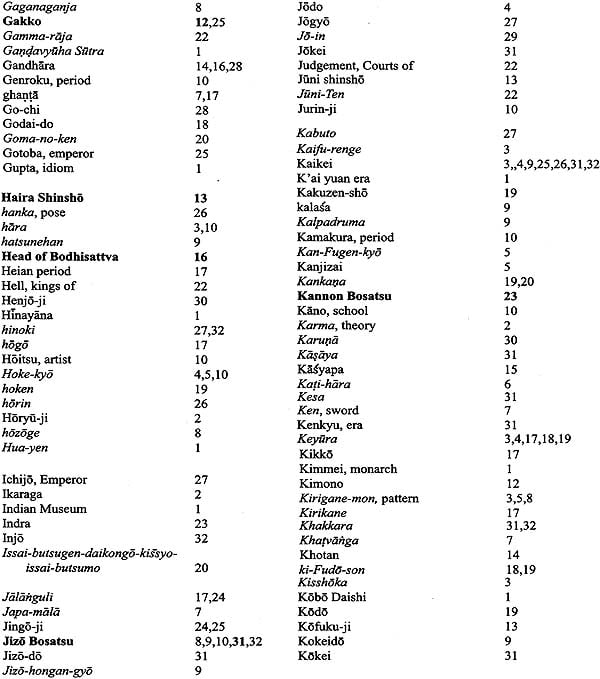

| Index | 42-46 |

| Plates of Tokyo Museum | 47-62 |

| Plates of Kyoto Museum | 63-78 |