Buddhist India

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDC134 |

| Author: | T.W. Rhys Davids |

| Publisher: | Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1997 |

| ISBN: | 8120804244 |

| Pages: | 347 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 7.2" X 4.8" |

Book Description

About the Book:

The present work portrays ancient India, during the period of Buddhist ascendancy, from the non-Brahmin point of view. Based on the literary, numismatica and inscriptional records, it throws light on points hitherto dark and even unsuspected.

Divided into sixteen chapters, the work presents a detailed account of the socio-economic, geo-political and ethico-religious conditions of the country. It describes at length the history of kings, clans, nations, vis-à-vis their role in the growth and spread of Buddhism. We get a clear perspective of the activities of Candragupta, Asoka and Kaniska -the principal characters in this performance. The Buddhist and kindred literature both in Pali and Sanskrit, with special reference to the Jatakas has been thoroughly exploited for this purpose.

The book has fifth-six illustrations, an appendix, a short preface and general index.

About the Author:

Thomas William Rhys Davids (1843-1922) was the foremost and most active exponent of the study of Pali and Buddhism in England. Rhys Davids studied Sanskrit at Breslau under Stenzler.

In 1882 he was appointed Professor of Pali in the University College, London. He was the Founder-Chairman of the Pali Text Society (1881), through which, by the time he passed away at the age of 80, he had published most of the basic texts and commentaries in Pali Buddhism, in about 25,000 pages.

Rhys Davids played an active part in founding, in 1902, the British Academy, and later the School of Oriented Studies, London. He was also the President of the India Society from its inception in 1910 till his death in 1922.

In the following work a first attempt has been made to describe ancient India, during the period of Buddhist ascendancy, from the point of view, not so much of the brahmin, as of the rajput. The two points of view naturally differ very much. Priest and noble in India have always worked very well together so long as the question at issue did not touch their own rival claims as against one another. When it did-and it did so especially during the period referred to-the harmony, as will be evident from the following pages, was not so great.

Even to make this attempt at all may be regarded by some as a kind of lese majeste. The brahmin view, in possession of the field when Europeans entered India, has been regarded so long with reverence among us that it seems almost an impertinence now, to put forward the other. “Why not leave well alone? Why resuscitate from the well-deserved oblivion in which, for so many centuries, they have happily lain, the pestilent views of these tiresome people? The puzzles of Indian history have been solved by respectable men in manu and the Great Bharata, which have the advantage of being equally true for five centuries before Christ and five centuries after. Shade of Kumarila! What are we coming to when the writings of these fellows- renegade brahmins among them too- are actually taken seriously, and mentioned without a sneer? If by chance they say anything well, that is only because it was better said, before they said it, by the orthodox brahmins, who form, and have always formed, the key-stone of the arch of social life in India. They are the only proper authorities. Why troub e about these miserable heretics?”

Well, I would plead, in extenuation, that I am not the first guilty one. People who found coins and inscriptions have not been deterred from considering them seriously because they fitted very badly with the brahmin theories of caste and history. The matter has gone too far, those theories have been already too much shaken, for any one to hesitate before using every available evidence. The evidence here collected, a good deal of it for the first time, is necessarily imperfect; but it seems often to be so suggestive, to throw so much light on points hitherto dark, or even unsuspected, that the trouble of collecting it is, so far at least, fairly justified. Any words, however, are, I am afraid, of little avail against such sentiments. Wherever they exist the inevitable tendency is to dispute the evidence, and to turn a deaf ear to the conclusions. And there is, perhaps, after all, but one course open, and that is to declare war, always with the deepest respect for those who hold them, against such views. The views are wrong. They are not compatible with historical methods, and the next generation will see them, and the writings that are, unconsciously, perhaps, animated by them, forgotten.

| I. | The Kings | 1 |

| II. | The Clans and Nations | 17 |

| III. | The Village | 42 |

| IV. | Social Grades | 52 |

| V. | In The Town | 63 |

| VI. | Economic Conditions | 87 |

| VII. | Writing- The Beginnings | 107 |

| VIII. | Writing- Its Development | 121 |

| IX. | Language and Literature. | |

| I. | General View | 140 |

| X. | Literature. | |

| II. | The Pali Book | 161 |

| XI. | The Jataka Book | 189 |

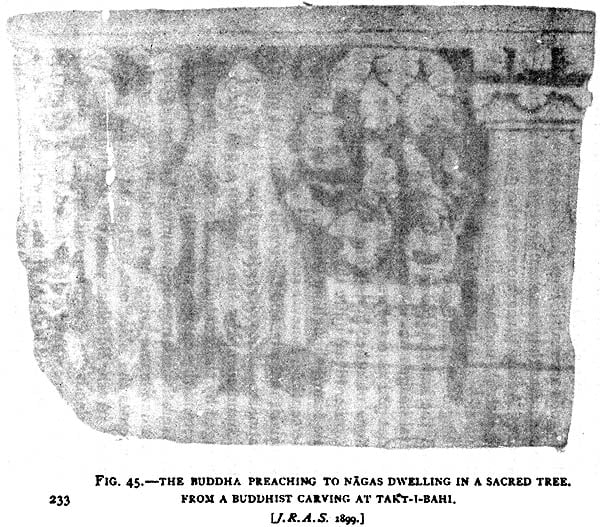

| XII. | Religion- Animism | 210 |

| XIII. | Religion- The Brahmin Position | 238 |

| XIV. | Chandragupta | 259 |

| XV. | Asoka | 272 |

| XVI. | Kanishka | 308 |

| Appendix | 321 | |

| Index | 323 |