Combating Corruption (The Indian Case)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAG221 |

| Author: | Yogesh Atal and Sunil k. Choudhary |

| Publisher: | Orient Blackswan Pvt. Ltd. |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2014 |

| ISBN: | 9788125052333 |

| Pages: | 307 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch X 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 480 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

With the exposure of major scams like 2G Spectrum, Commonwealth Games and Adarsh, public anger against corruption boiled over as witnessed in the massive protests of 2011-12.

Combating Corruption: The Indian case provides a perspective for viewing the increasing levels of corruption in the higher echelons of politics and bureaucracy in post-Independence India, and the limits of popular struggles and legislative/administrative measures to combat it. Looking at the phenomenon as 'deviance' from norms and a systemic dysfunctionality, the authors argues that it can be resisted by effective strategies of mass mobilization under charismatic leaders. Focusing on peoples' participation, it traces the emergence of anti-corruption movements to the JP Movement of the 1970s and culminates with protests led by Anna Hazare and Baba Ramdev and the rise of the Arvind Kejriwal led Aam Admi Party.

The book fills a major lacuna in our sociological understanding of corruption, as exemplified by cases of grand embezzlement, and the popular opposition to it. Identifying the traditional sources of corruption, the authors show how the problem manifests itself in the social, economic and political contexts peculiar to India. And in doing so, they underline the crucial role of state institutions and a vigilant civil society in tackling a problem that afflicts almost all, and not only the developing, societies.

As 'instant history', Combating Corruption is an account of an unprecedented phase of mass protests in India. A must-read for political analysts, sociologists, journalists and general readers alike, it is indispensable for understanding contemporary India.

About the Author

Yogesh Atal was Principal Director of Social and Human Sciences at UNESCO from 1974 to 1997. He has written extensively on development-related issues, political processes and the Indian social structure.

Sunil k. Choudhary is Associate Professor of Political Science at Shyam Lal College (Evening), University of Delhi.

Introduction

In the past two to three decades, the question of corruption has come to the centre stage of all public discourse, national and international. International groupings have taken a serious view of this growing menace, and have taken steps to assist member states in stemming it. Reviewing the progress made on the development front, it was generally acknowledged by the world community that while progress has been registered on a number of indicators of modernization such as literacy rate, urbanization, economic growth and political participation, there continues to be a huge deficit on the social front. Failure of development judged in terms of continuing deficits, particularly in the social sphere, is attributed to the issue of governance. And corruption in administration is regarded as one of the key indicators of bad governance or misgovernance. The Unite Nations accorded a key priority to this concern after it was highlighted at the World Summit for Social Development in Denmark in 1995. Efforts are now being made to understand this phenomenon and find ways to mitigate it. We briefly allude to the steps taken at the international level to fight corruption.

Following the World Summit for social Development, one of the task forces set up consisting of representatives from various UN agencies was on good governance. The task force highlighted the problem of corruption as a major stumbling block in promoting good governance. It commissioned case studies from countries across the world, of 'best practices' exemplifying good governance, to publicise them, and to encourage member states to examine them with a view to their replication or adaptation in their respective contexts. Most of such studies related to cases that have improved efficiency, maximized economy of effort, and minimized harassment to the general public.

Such efforts notwithstanding, corruption is spreading and assuming newer forms. And this is true for a large number of societies, not just the Least Developed Countries (LDCs). The 2011 Corruption perceptions Index shows that no region or country in the world is immune to the problem of corruption. The vast majority of the 183 countries and territories assessed had scored below five on a scale of zero ('highly corrupt') to ten ('very clean'). New Zealand, Denmark and Finland top the list coming close to very clean, while North Korea and Somalia are at the bottom. India has a score of 3.1 and is ranked ninety-fifth in the list of 183 countries.

Corruption is, thus, a common problem faced by many governments. There is, however, an emerging consensus to eliminate it. The international community feels that corruption, particularly systemic corruption, impinges on the rights of people; in fact, it is regarded as a violation of human rights. The international community now seems to be determined to fight this menace, as is reflected in the various conventions, declarations, covenants, etc., adopted under the auspices of the UN to which individual governments are signatories. It is in the same direction that the UN adopted the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) in 2005. This is, in fact, a step to further the aims of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Right (ICCPR), ADOPTED WAY BACK IN 1966.

UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUTION, 2005

The General Assembly of the UN passed, through its Resolution 58/4 on 10 January 2005, the UNCAC. It has already been signed by 116, and ratified by fifteen member states. The convention is intended to:

Promote and strengthen measures to prevent and combat corruption more efficiently and effectively; Promote, facilitate, and support international cooperation and technical assistance in the prevention of, and fight against, corruption, including in asset recovery, and Promote integrity, accountability, and proper management of public affairs and public property.

In his Foreword to the brochure carrying the convention, the then Secretary-General of the UN, Kofi A. Annan, wrote: Corruption is an insidious plague that has a wide range of corrosive effects on societies. It undermines democracy and the rule of law, leads to violations of human rights, distorts markets, erodes the quality of life and allows organized crime, terrorism and other threats to human security to flourish. This evil phenomenon is found in all countries big and small, rich and poor but it is in the developing world that its effects are most destructive. Corruption hurts the poor disproportionately by diverting funds intended for development, undermining a government's ability to provide basic services, feeding inequality and injustice and discouraging foreign aid and investment. Corruption is a key element in economic underperformance and a major obstacle to poverty alleviation and development. The adoption of the United Nations Convention against Corruption will send a clear message that the international community is determined to prevent and control corruption. It will warn the corrupt that betrayal of public trust will no longer be tolerated. And it will reaffirm the importance of core values such as honesty, respect for the rule of law, accountability and transparency in promoting development.

The issue of corruption is being addressed by financial institutions, governments, bilateral donors, international organizations, Non-governmental Organizations (NGO) and development professionals. There is now a Global programme against Corruption run by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), which has the responsibility of helping member states in implementing the UNCAC.

There are agencies like the Transparency International that have taken up the task of exposing cases of corruption at the international level. It developed the Global Corruption Barometer in 2003 to draw up country-wise graphs of corruption and put all the countries on a single scale. In a survey carried out in countries across the world, simple questions were asked: Have you paid a bribe? Has corruption increased in your country? Is your government effectively tackling corruption? These questions were then analyzed and computed nation-wise to arrive at the Corruption Perceptions Index.

The stated aim of the Transparency International is to empower individuals to make informed decisions and to limit opportunities for abuse of power by the officials. It is 'a global network including more than ninety locally established national chapters.These bodies fight corruption in the national arena in a number of ways. They bring together relevant players from government, civil society, business and the media to promote transparency in elections, in public administration, in procurement and in business. [The Transparency International's] global network of chapters and contacts also use advocacy campaigns to lobby governments to implement anti-corruption reforms'. It 'challenges the inevitability of corruption, and offers hope to its victims'. And it 'has the skills, tools, experience, expertise and broad participation to fight corruption on the ground, as well as through global and regional initiatives. Now in its second decade, Transparency International is maturing, intensifying and diversifying its fight against corruption.

THEORETIC APPROACHES

It is interesting to note that despite much public debate on corruption, there is very little by way of empirical research. Of course, economists have tried to explain this phenomenon with their special perspectives, and have also used mathematical tools to gauge the extent of loss caused due to the prevailing corruption. A few other social scientists have labored to draw the contours of a sociological theory, and some others have written case studies; but the scope of this phenomenon is very side and it still remains largely a virgin territory.

We begin with the assumption that corruption is a phenomenon that prevails in all societies. Also, that everywhere it is negatively rated. Yet, there is no society that has succeeded in eliminating it completely. It may be uprooted from one part of the system, but its occurrence in other parts, or in other forms, cannot be ruled out. But this fact does not deter people from expressing their angst against it, and taking steps to combat it. As an act of moral violation, corruption thrives where societal radars monitoring corruption remain weak. Corruption has an inherent vitality that help it to persist and grow to alarming proportion particularly when the mechanisms of social control somehow fail in the task of its detection and awarding due punishment to the offenders.

It is the responsibility of society to seal the seepage points to prevent the onslaught of corruption; but there is no guarantee that the deviants would not locate alternative spots that are vulnerable. The impossibility of a corruption-free administration has also been asserted by Kautilya, the perceptive and astute lawmaker of ancient India. His argument runs somewhat like this:

Just as it is impossible not to taste the honey or the poison that finds itself on the tip of the tongue, so it is impossible for a government servant not to eat up, at least a bit of the king's revenue. Just as fish underwater cannot possibly be found out either as drinking water or not drinking water, so government servants employed in government work cannot be found out taking money.

In a democratic setting, the proverbial fish of Kautilya's allegory needs a redefinition as regards its composition. Kautilya's reference was to a monarchial system where the king was above reproach and his minions were the privileged creatures who could defraud the royal exchequer. In a democracy, the transient rulers and entrenched bureaucracy jointly misappropriate the resources that they are asked to manage on behalf of the people. Today, the rulers and the bureaucracy jointly are the fish, albeit of a different king. The rulers elected representatives of the people usually have a shorter stint in the administrative waters as compared to the bureaucrats, who are the old workhorses. The change of the ruling elites within stipulated time frames makes them not only vulnerable, but also more desperate to drink as much water the pool as possible before they are flushed out. Had the political sphere been economically no-yielding, many actors in that sphere would not have been there. The enormous amount of money spent in getting the mandate of the people from municipal and panchayat elections to elections to Legislative Assemblies in States, and further up to Lok Sabha is a clear indication that this money is an investment to be earned back with high dividends. Politics has become a game of muscle power and money power. Earlier, politicians hired musclemen for their protection, and lured moneyed men with favours in return for generous contributions towards party funds. Now these two kinds of people the musclemen and the moneyed men have also begun to play the role of politicians. In recent times, names of tainted ministers and legislators with criminal antecedents have been exposed. The number of such persons has been growing over time. It emerges that while despotic regimes like monarchies and dictatorships provide opportunities for a typical form of corruption, the democratic regimes are fertile grounds for other types of corruption. We, therefore, need a theoretical orientation that encompasses all forms of corruption in different political systems. Our focus in this exercise, however, is on India; and that too on India after Independence, when its government changed from a colonial to a democratic one. Therefore, we shall refrain from over-the orising, and settle for the broad contours of a sociological paradigm for the study of corruption.

In the initial phase of India's Independence, elected representatives were respected for their complete probity. Today, many politicians derive their prestige differently. While people with clean records are still found in the political arena, they are being outnumbered by the other kind that have corrupted the system and have gained immensely; from the prevailing social climate. It is their growing number and the routine exposure of scams that has evoked the wrath of the people and brought corruption into the centre stage of political debates. It must, however, be emphasized that the type of corruption that is generally described as 'retail corruption has not been replaced by this high-profile corruption. As the continuation of a practice that was consolidated during the colonial period itself, people somehow got used to petty corruption, i.e., retail corruption. While expressing disapproval for the corrupt and inefficient local-level administration, people somehow have learnt to live with it as part of the routine culture. Occasional outbursts against such retail corruption apart; it has become an accepted fact of contemporary society.

It is, however, the corruption of huge magnitude in high places that directly hurts the public funds and leaves people in dismay that has provoked mass anger and goaded the people to agitate against and combat it. Since more and more cases of corruption are now being revealed, the people's anger against it is also a recent phenomenon. The exposes of the ruler-bureaucrat nexus consuming the pond water as the 'fish incurs the wrath of the people who are the rightful owners of the pond. This has resulted in widespread concern and an urge to ensure the protection of resources.

It must be admitted that even though corruption has spread in epidemic proportions and is universally disapproved, it remains a relatively less-researched phenomenon. Whatever is published is by way of stories about cases that were detected. Then, there are opinionated statements against corruption with moral undertones. Official statements are also in terms of 'statistics' providing the numerical incidence of various types of corruption in the governmental sphere; and commissions set up by the government use such material to recommend administrative reforms. In economics, there is a modicum of work that has focused on the structures that facilitate corruption. Many economists have employed 'bribe-based measures of corruption' including cross-country regressions and other types of statistical exercises. But even amongst them, there is no agreement on the definition of corruption. They differ in terms of underlying assumptions and the specific country-wise experiences. There is no agreement as to whether corruption should be measured 'by total bribes, or some per capita measure (e.g., relative to the number of potential bribe-givers, or bribe-takers), or the level of economic activity in the sector or economy in question'. In other social science disciplines, there is not much work to depend on. The situation is precarious when we hunt for relevant studies on India. S.L. Sharma laments: "The popular upsurge against it notwithstanding, corruption has not received as much attention in social sciences, as it deserves, except a bit in economics and public administration. While economists have sought to explore the linkages between corruption and development leading to an engaging debate about it, the scholars of public administration have addressed the issue of corruption and quality of governance.'

Way back in 1963, when very little by way of research on corruption existed in social science literature, Harold J. Lasswell and A.A. Rogow (1963) came out with a book titled power, Corruption, and Rectitude. At a time when the topic of corruption had hardly attained the status of a science concept, these two authors undertook this exercise to logical examine Lord Action's oft-quoted phrase: 'Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely'. Analysing the experience of American politics, they dispute the dictum and courageously say that the opposite may, indeed, be truer. They offer the view that power may actually ennoble rather than corrupt. The authors go on to argue that the distrust of power epitomized by Lord Acton has created difficulties for the government in functioning effectively. They argue that the problem of public corruption needs to be dealt with in terms of a rapidly changing, larger social context.

It in that spirit that Lasswell welcomed the 1968 publication of The Sociology of Corruption: The Nature, Function, Causes and Prevention of Corruption by the Malaysian scholar Syed Hussein Alatas. Lasswell writes in his foreword to the booklet: 'Few short treatises can be more timely than the exemplary sketch of the problem of corruption.' 'Alatas 'deflated many hypotheses that have been put forward to account for some of the corruption that has so often appeared during the years of transition from a 'traditional' society'. Alatas' pioneering work attempts to define several concepts and also to prepare a typology of corruption. The merit of the work lies in its being thoroughly contextual rather than overly theoretical. Examples drawn from his personal experience of living in two major countries of Southeast Asia Malaysia and Indonesia have shown the importance of viewing corruption in a particular cultural context. Endorsing such an attempt, Lasswell says that 'significant dimensions are only revealed when it is possible to identify the particular constellation of factors present in a given place and at a definite time and to ascertain their relative weight in stimulating or inhibiting corruption'. Alatas divides corruption into three stages in terms of its coverage. In the first stage, 'corruption is relatively restricted without affecting a wide area of social life'; in the second, it becomes 'rampant and all-pervading'; and then it reaches the final stage when it becomes self-destructive'. Obviously, his suggestion is to curb it before it reaches such destructive proportions. His distinction between the type of corruption that helps the corruptor but does not hurt anyone else, and the other type that hurts others while benefiting the corruptor, is interesting. Implicit in the distinction is the point that it is the latter type that is worrisome, while the former is an expedient measure in self-interest the corruptor willingly pays to get

Matters expedited and are not coerced to pay. The merit of the Alatas' book lies in making an attempt to heuristically classify the variants of corruption so that they could be cross-culturally verified. Alatas also stresses the significance of the manner in which people in a given society justify or criticise actions that fall within the ambit of corruption.

Contents

| List of Figures and Tables | Vii | |

| Prologue | Ix | |

| List of Abbreviations | XV | |

| Introduction : Articulating the Concern about Corruption | 1 | |

| PART ONE | ||

| Corruption : Asocial Social Perspective | ||

| 1 | Conceptualizing Corruption | 27 |

| 2 | Causes of Corruption | 46 |

| 3 | Stages and Spheres of Corruption | 65 |

| PART TWO | ||

| Corruption Syndrome in India | ||

| 4 | Pious Platitudes and Perfunctory Pledges | 79 |

| 5 | Indian Initiatives to Curb Corruption | 86 |

| 6 | The Rising Graph of Corruption in India | 100 |

| PART THREE Expression of Public Anger | ||

| 7 | The Three Crusaders : Jayaprakash Narayan, Ramdev and Anna Hazare | 135 |

| 8 | Ramdev's First Rally at Ramlila Maidan, February 2011 | 151 |

| 9 | Anna's Fast at Jantar Mantar, April 2011 | 155 |

| 10 | Ramdeve's Second Rally at Ramlila Maidan, June 2011 | 166 |

| 11 | Anna's Agitation at Ramlila Maidan, August 2011 | 186 |

| 12 | Post-August 2011 Events Leading to the Mumbai Fiasco | 207 |

| 13 | Anna's Rally at Jantar Mantar, July-August 2012 | 219 |

| 14 | Ramdev's Third Rally at Ramlila Maidan, August 2012 | 225 |

| Conclusion: Tying the Threads Together | 232 | |

| Epilogue | 267 | |

| APPENDIX Preamble to the United Nations Convention against Corruption | 273 | |

| Bibliography | 277 | |

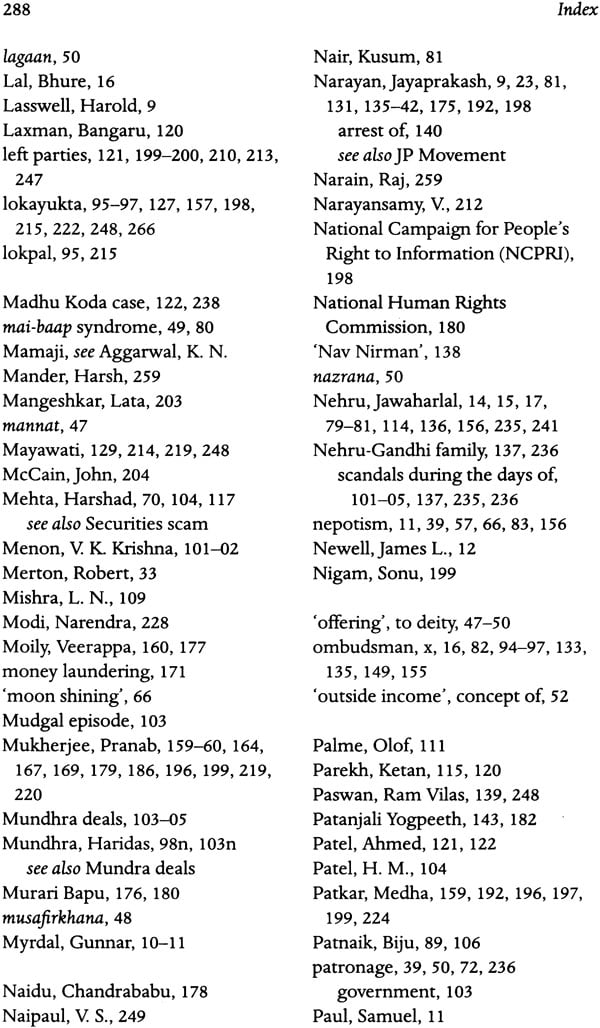

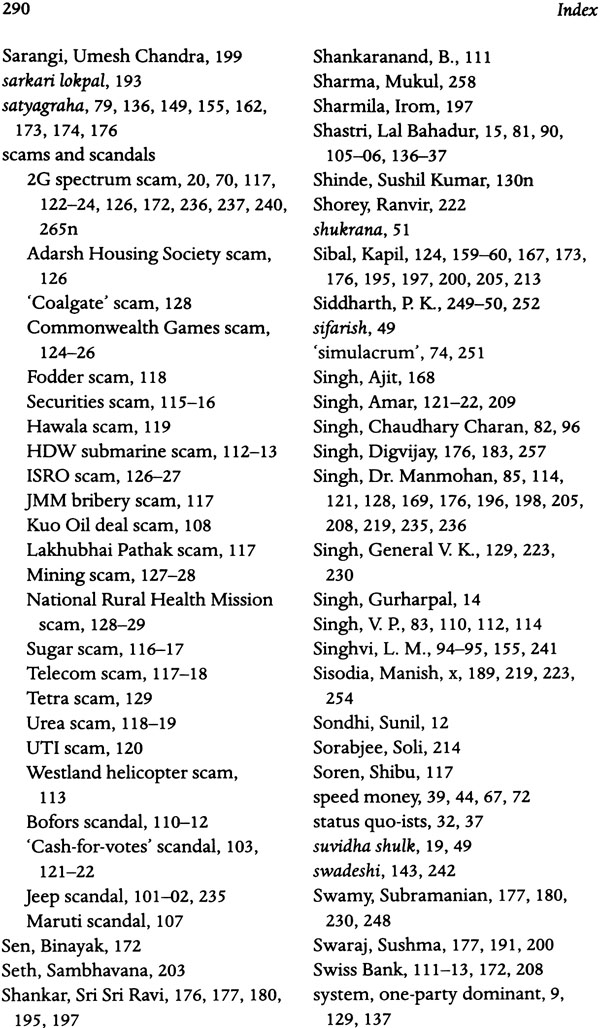

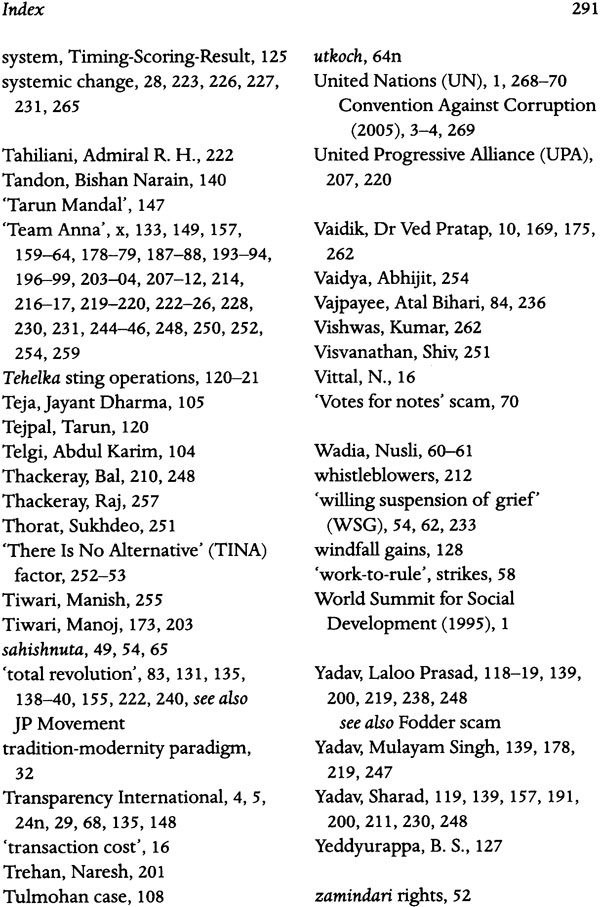

| Index | 283 |