A History of Urdu Literature

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAR319 |

| Author: | Ali Jawad Zaidi |

| Publisher: | SAHITYA AKADEMI, DELHI |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2017 |

| ISBN: | 9788172012915 |

| Pages: | 480 |

| Cover: | PAPERBACK |

| Other Details | 8.50 X 5.50 inch |

| Weight | 590 gm |

Book Description

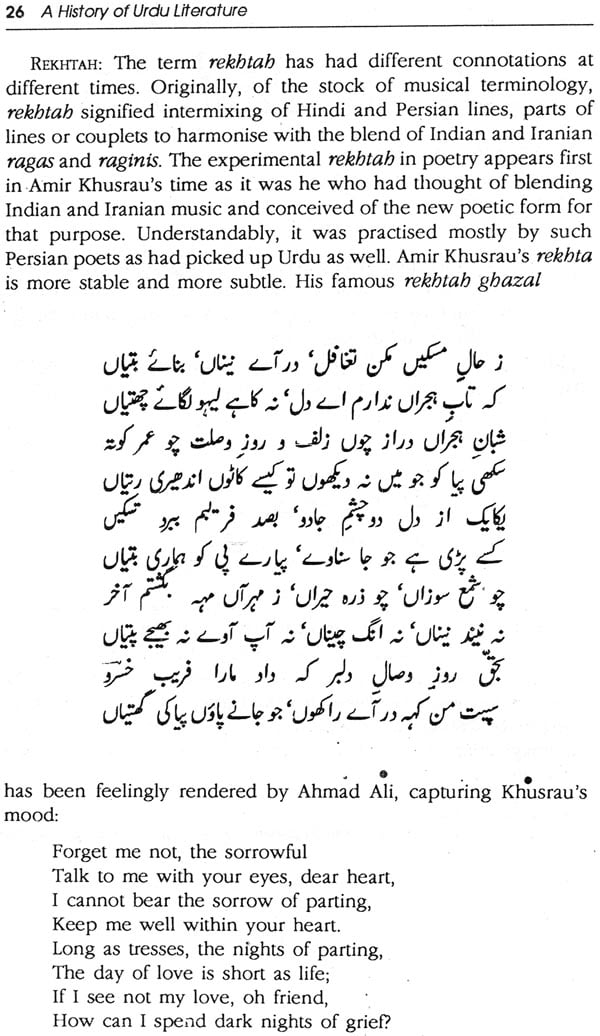

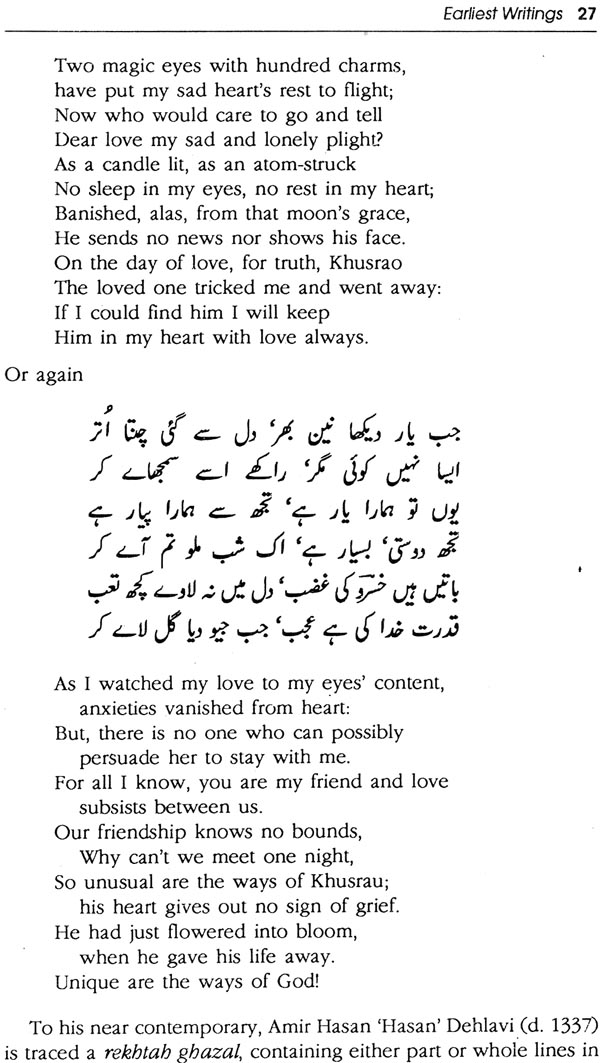

A History of Urdu Literature seeks to present a compact survey of the rich and varied contribution of Urdu to the Indian literary mainstream through centuries of shared creative endeavour and inspiration. Designed to serve as a reliable guide for interested readers from sister languages, it brings into focus the currents and cross-currents that have shaped its history and produced personalities of distinction and prestige whose works have stood the test of time. The lucid and balanced treatment of the numerous forms of poetry and prose has both range and depth and reveals a broad understanding of the historical forces behind deviations from convention and transformations in styles that have given us pernennial sources of joy and intellectual fulfilment.

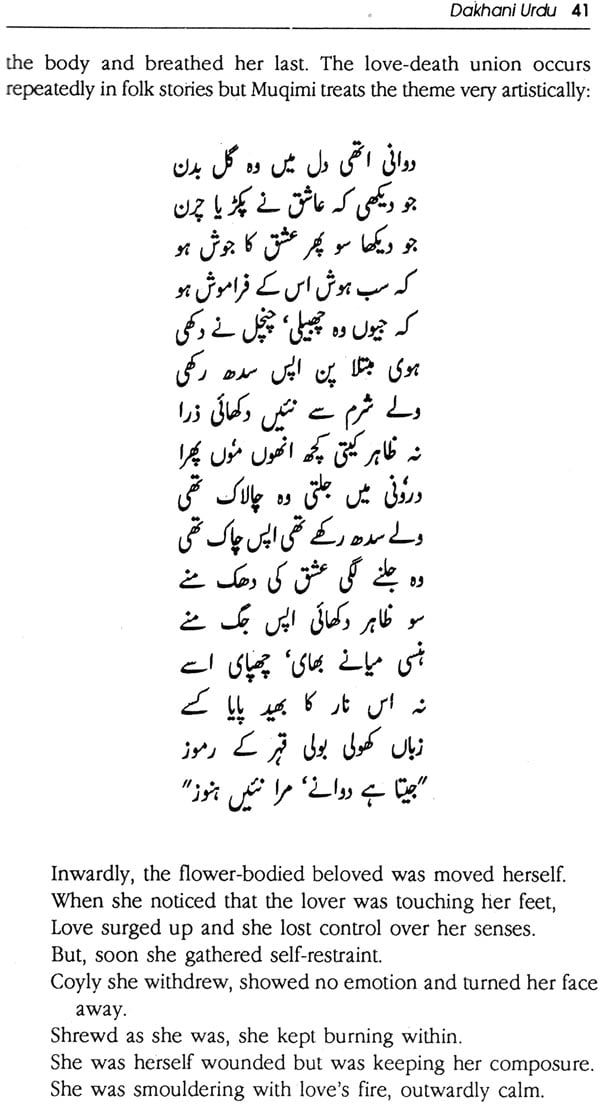

The dynamism of its patriotic poetry, in particular, during the various phases of our freedom struggle and the cohesive absorption of the classical works of all the major religions have been highlighted appropriately. The vigorous role of journalism has also received due notice. Despite pressure on space in the brief survey, essential specimens of poetry have been added in the original along with prose renderings in English, to mirror the conflicting demands of a vibrant tradition of lyricism, fervor of nationalism and a resurgence of social realism.

Ali Jawad Zaidi (1916-2004) a scholar, poet and critic of repute, had won the Padmashri Award for his meritorious services in the field of literature. Author of about 60 books, he has written in Urdu, Hindi, English and occasionally in Persian as well. In the present volume, written primarily for the non-Urdu readers, he surveys, evaluates and interprets the achievements of the language with a rare fairness and understanding.

India is a country of vast dimensions with varying cultural scenario and numerous languages. In the first major linguistic survey, Grierson identified as many as 179 languages and 544 dialects and, he had by no means exhausted the list. Further research took the figure to 1673 languages and dialects in the census of 1971. In the midst of this baffling variety, however, it is not difficult to discern the thread of historical unity running through them all. This represents a remarkable process of creative synthesis and assimilation. In surveying the history of Urdu literature, we need to consider this wide national canvas and the various socio-cultural movements and political upheavals that the country witnessed during the centuries that moulded our personality as a nation and set the pattern for linguistic growth.

Today Urdu is a major Indian language, spoken and cultivated from Kashmir to Kanyakumari and from Gujarat to West Bengal. Across our borders, it is used in Pakistan and much excellent literature has emerged, particularly from the Punjab province which dominated the literary scene even in the pre-partition era. The North West Frontier, Sind and Baluchistan have also large concentrations of Urdu speakers. In more recent decades, the language has travelled far beyond its traditional frontiers and established active nuclei in Great Britain, the United States, Canada and some of the Scandinavian, West Asian and African countries. The number of its speakers is estimated to be around 100 millions. In India alone the number has crossed 60 million speakers, while unofficial sources claim the figure to be much higher. With all this, it faces the predicament of not getting a regional language status in any State or Union Territory other than Jammu and Kashmir, because of the wide dispersal of its speakers. In Jammu and Kashmir also it shares the honour with Kashmiri, Dogri, etc. but functions more as an inter-regional link. Despite this lack of concentration it continues to remain the most widely spoken language. Millions of students are engaged in learning it from the primary to the post-graduate level. Urdu films draw packed houses all over the country while poetic symposia, mushairas, attract thousands of listeners even in remote corners. Next to English, it covers almost the entire country through its newspapers, journals and books, which are published in thousands from most of the States and their number is on the increase, notwithstanding the handicap that it is not the majority language of a compact region which would entitle it to full State patronage.

The language scene underwent a radical change after Independence in 1947 when the monopolistic position of English as the sole official language and the main medium of instruction ended. Hindi along with several regional languages came to the fore to fill the void. Soon thereafter there came the linguistic reorganisation of States. These events led to the adoption of the predominant language as the regional language of each area. In the population hierarchy, Urdu stands sixth. Its speakers far outnumber those of Assamese, Gujarati, Kannada, Kashmiri, Malayalam, Oriya, Punjabi, besides of course Sanskrit and Sindhi. According to the 1971 Census, Urdu was the second largest spoken language in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Mysore and Uttar Pradesh and the third largest in Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan and West Bengal, besides the Union Territories of Chandigarh, Delhi and Goa, Daman and Diu. At the official level, Urdu is the main official language in Jammu and Kashmir and has acquired the status of a second language in Andhra Pradesh and Bihar and in Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal there is a demand for its declaration as the second official language. In Pakistan it has been declared the state language for its capacity to serve as a link language between the different regions although it has not been able to replace English in government offices.

The general assumption that Urdu is an "urban" language is erroneous. In 1971, the percentage of Urdu-speaking people in the rural areas of India was as high as 52.67.

Urdu claims the same family history with Hindi. Even a cursory glance at the history of evolution of Urdu is sufficient to convince the reader of its importance as a national language. People of all regions and creeds have nurtured it with great love and care over the centuries. It has inherited the mood, the sentiment and the cultural inspiration from Sanskrit and the folk traditions from its cousins, the numerous Indian dialects. In a long historical process it assimilated Persian, Arabic and English vocabulary and literary styles and enriched its literary tradition by borrowing fresh knowledge and new trends from whatever quarters they came. This liberal temperament has helped it to retain its vitality and to mature into a modern language with a magnificent literature, fully responsive to changing times and yet maintaining its own identity and Indianness.

Unfortunately, no systematic effort has been made to unravel the process of its rise ad spread. The works of Garcin de Tassy, Fallon and Karimuddin, Graham Bailey, Mohammed Hussain Azad, M. Abdul Hayfy, Abdus Salam Nadvi, Ram Babu Saxena and Mohammed Sadiq brought together some useful material but a complete, research-based history of the language is yet to come. Aligarh Muslim University had planned a five-volume comprehensive history but only one volume has been published so far. The project has been undertaken also in Pakistan, under the supervision of the Jamil Jalibi. Three volumes are already out and a few more are expected. There have been a number of concise historical surveys of which those by Mohammed Baqir, Eijaz Husain and Ehtesham Husain need special mention. Informative as these are, many of their assumptions and formulations require revision to accommodate recent research findings. I had myself attempted a brief historical survey for the Report of the Committee for Promotion of Urdu set up by the Government of India and it has been included as one of its chapters. As was inevitable in a compilation of that nature, it gave but the barest outline. The present work endeavours to update the information as far as possible. Research, however, is a continuous process and no one can claim to have written the last word.

One of the many difficulties one encounters in writing the history for English knowing readers pertains to English renderings of Urdu poetry. I have tried to borrow a few translations from others to whom my thanks are due for having very kindly agreed to the reproductions. These however, do not touch even the fringe. In most cases it is a plain prose rendering conforming almost literally to the original text. In some cases it became necessary to illustrate my ideas with original quotations, for it would not be possible otherwise to comprehend the changes in language and style that have occured from time to time.

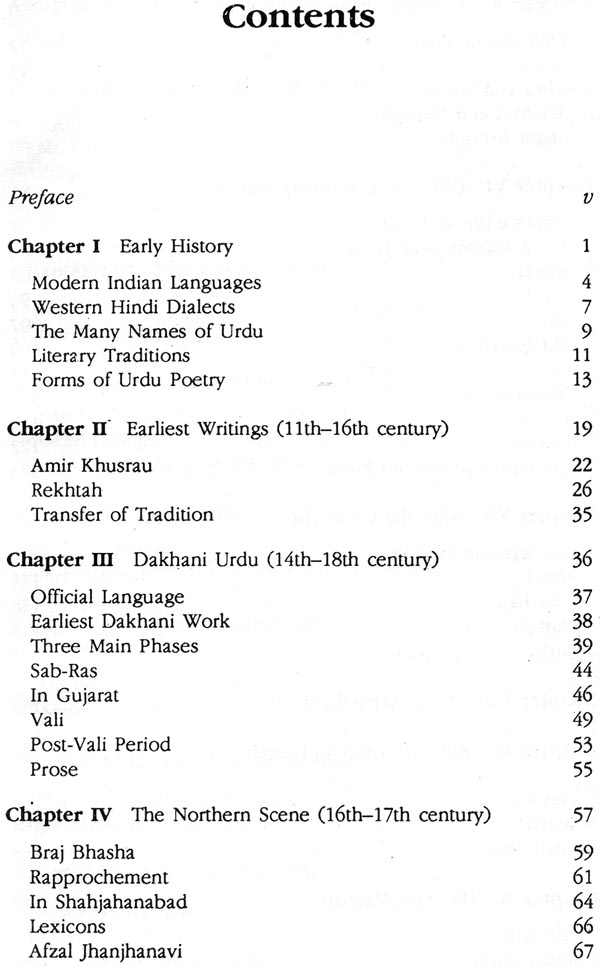

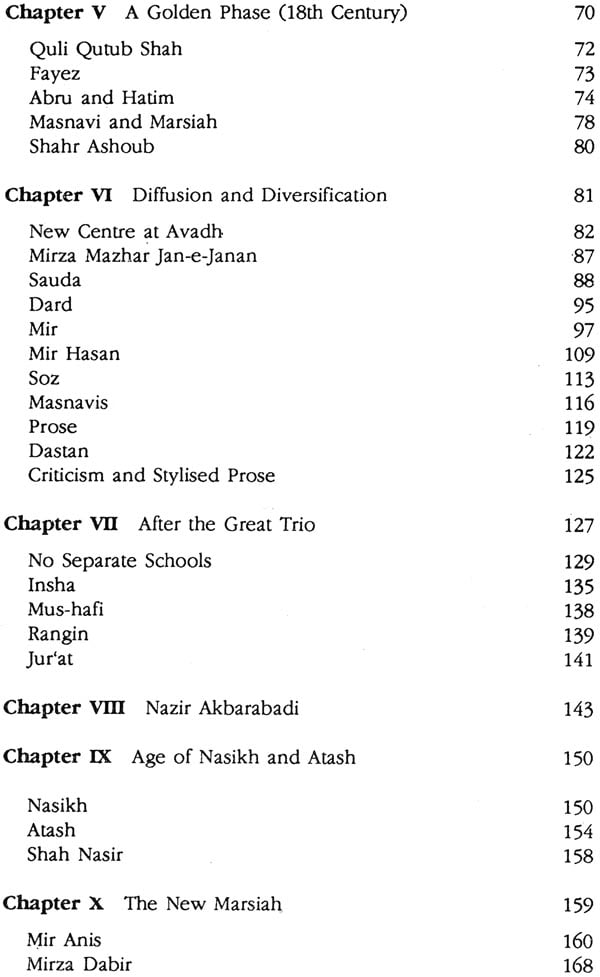

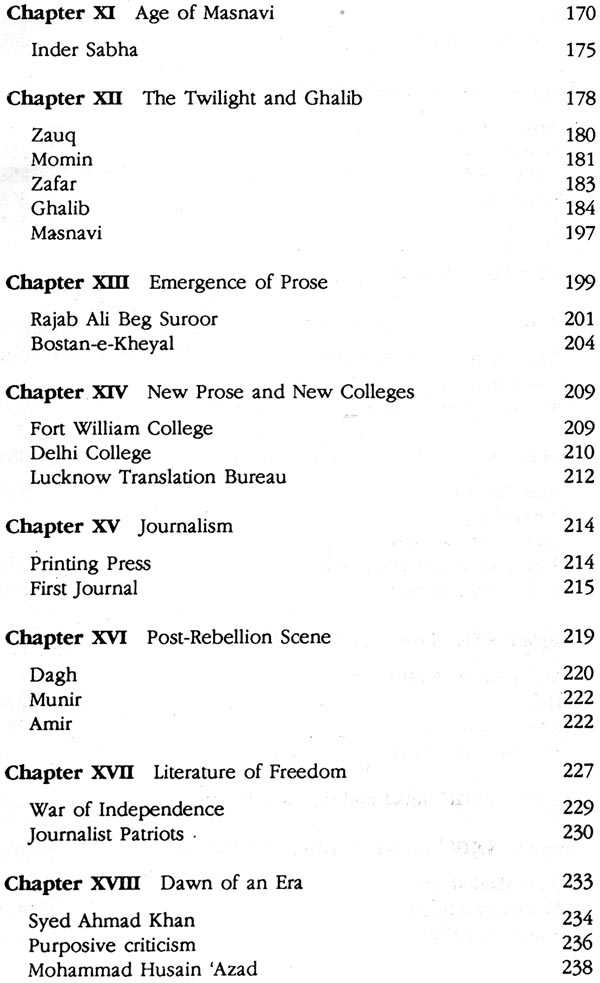

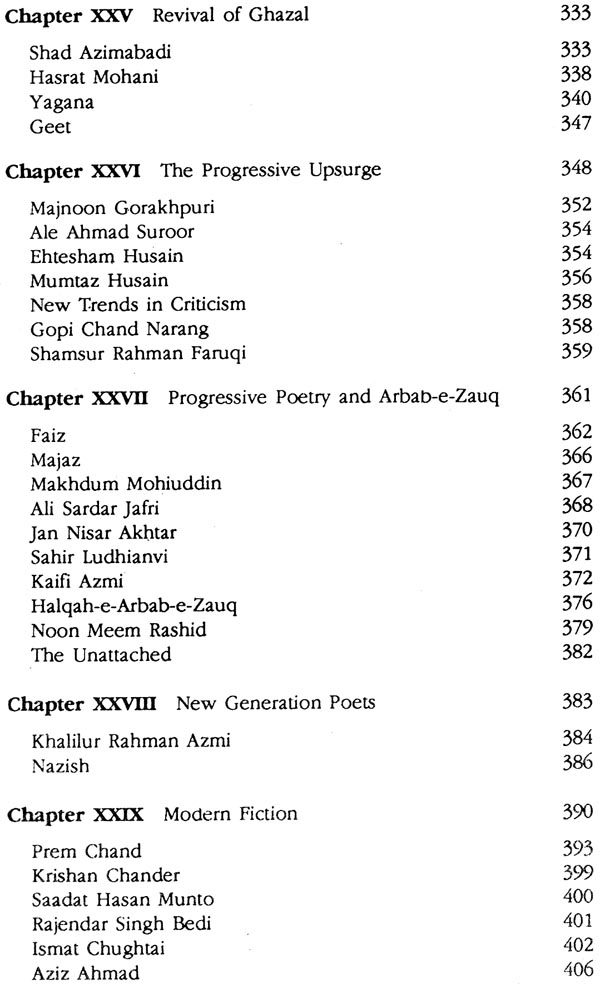

**Contents and Sample Pages**