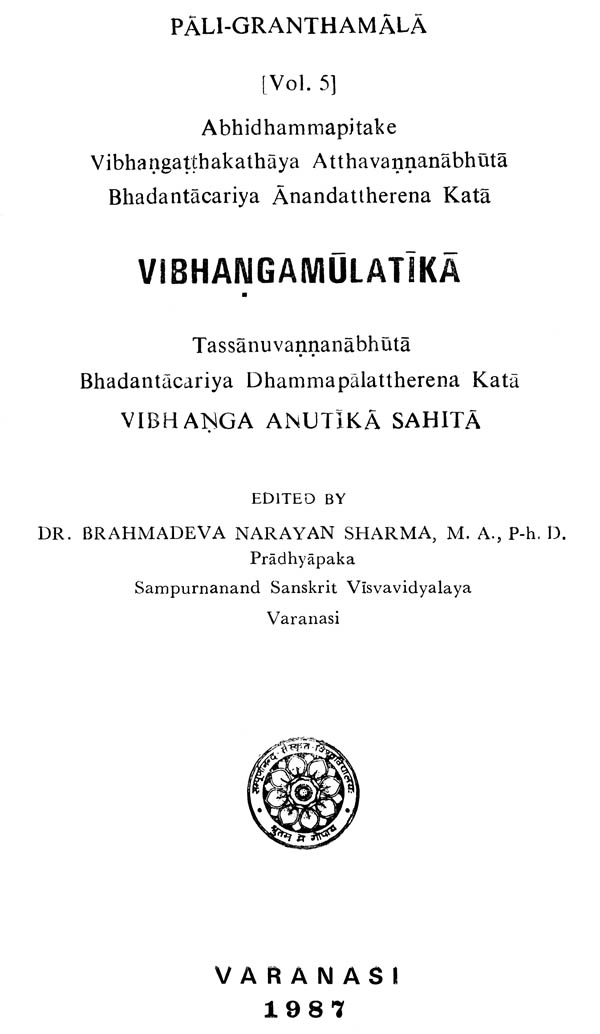

विभङ्गमूलटीका: Vibhangamulatika

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NZD531 |

| Author: | डॉ. ब्रह्मदेव नारायण शर्मा (Dr. Brahmdev Narayan Sharma) |

| Publisher: | Sampurnanand Sanskrit University |

| Language: | Sanskrit |

| Edition: | 1987 |

| Pages: | 482 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 10.0 inch X 6.5 inch |

| Weight | 990 gm |

Book Description

It is with a sense of supreme satisfaction that I place this publication of our University in the hands of scholars. Dr. Brahmadeva Narayana Sharma, the learned editor of this book has placed the world of scholars of Buddhist Philosophy in India under a deep debt of gratitude by making these basic texts available to Indian scholars for the first time through the present Devanagari edition of two authoritative Pali commentaries on Vibhanga literature, which forms part of the Buddhist canon. Though the present publication is not the editio princeps of any of the two commentaries here, it has all the value of an editio princeps for our readers here. The reason is simple. The two commentaries published here have so far been available only in Burmese script and were, therefore, more or less a sealed book to the generality of students of the Philosophy of Buddha, who cannot read Burmese script. The existence of the present commentaries was, no doubt, well known through notices in Histories of Pali or Buddhist literature from the days of the German pioneer, Wilhelm Geiger, who wrote his Pali Literature and Sprache (translated into English by Dr. Bata Krishna Ghosh in his Pali literature and Language) and in the more exhaustive history of Pali Literature in Hindi by Dr. Bharat Simha Upadhyaya –Pali Sahitya ka Itihasa- published by the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Prayag, as well as in other similar treatises. Though scholars may have known that these commentaries in Buddhaghosa's Atthakatha were valuable tools for the in – depth study of Buddhaghosa's earliest exposition of the Vibhanga text and for a proper appreciation of its nuances, these commentaries could not scale the geographical walls of Burma, on account of the constraints imposed by the script.

It is, therefore, in the fitness of things that Dr. Sharma should have harnessed his knowledge of Burmese language and script to the service of such Buddhist texts by preparing this Devanagari edition of the two commentaries. I cannot help recording my feeling that if only the original Vibhanga canon and the Atthakatha of Buddhaghosa in it had also been included here alongside with these; it would have been of considerable assistance to scholars, as it would have brought the original canonical text and the three commentaries within a single compass. It would have, no doubt, swelled the size of the volume, but would have completed the quadruple commentary- chain and would have presented a compact whole of the Vibhanga literature. Scholars have now to content themselves with keeping the two earlier originals side by side to read and follow these commentaries.

Attention has frequently been drawn to this strange about the early Indian mind that it evinced a queer genius to express itself through commentaries in the works of great masters, rather than through independent treatises. This had also become the subject of much criticism from the west. Some have branded it as unwise or unpractical or as just unfortunate, whereas more severe critics have averred that it betrays lack of individuality and originality or even that it smacks of intellectual bankruptcy. Though there may be some little measure of truth in such charges, in respect of some latter-day commentaries, the position of the major basic commentaries in every discipline is certainly different. It is also not true that this is a typical tendency of the decadent period of India's cultural history. Though this trend did assume conspicuous dimensions in the mediaeval period, its beginnings are traceable right in the pre-Christian era. The Panini-Katyayana –Patanjali chain is an instance in point. This triple commentary-chain, which constitutes the foundation for the whole edifice of Sanskrit Grammar, links the Sutra of circa 6th Century B.C with the Bhasya of the 2nd century B.C through an intermediary commentary of the Vartika genre, placed somewhere between these two terminuses. Will any one who has even a nodding acquaintance with the Mahabhasya or the Vertika ever dare question the intellectual independence of their authors? Commentaries, though they are, bear the hall mark of originality and intellectual virility, rarely equalled else-where. The best proof of this is the basic dictum, postulated by our traditional grammarians, that among these three writers, the succeeding one was more authoritative than the one or ones who preceded; meaning thereby that the Vartika commanded greater authority than the Sutra and the Bhasya was more authoritative than both. The obvious implication is that the commentator superseded the original writer, in point of authority!

This is not a solitary case when we turn to philosophy, the same tend of writing commentaries on earlier standard works to build up new original systems of thought is very much in evidence. In the field of Vedanta, for instance Sankaracarya and all the great Acaryas who came in his wake built their philosophical systems of Advaita, Visistadvaita, Dvaita, Suddhadvaita, Sakti-Visistadvaita and so on, through their commentaries on the Upanisads, Bhagavadgita and the Brahmsutra, which taken together, comprise the traditional prasthanatraya. And what is still more thrilling, the disciples and followers of these founder-Acaryas too kept up this trend and wrote more commentaries to build up their own subsystems! The Vivarana-Prasthana and Bhamati-Prasthana, within the fold of Acarya Sankara's Advaita are the products of two separate commentary-chains- the pancapadika-Vivarana-Tattvadipana chain, on the one hand, and the Bhamati –Kalpataru-Parimala chain, on the other. And what is truly breath-taking about all these six commentaries comprising the two chains is the fact that the writer of every one of these commentaries is an independent thinker in his own right and has his specific contribution to make within the fold of Advaita.