Vitalistic Thought in India

Book Specification

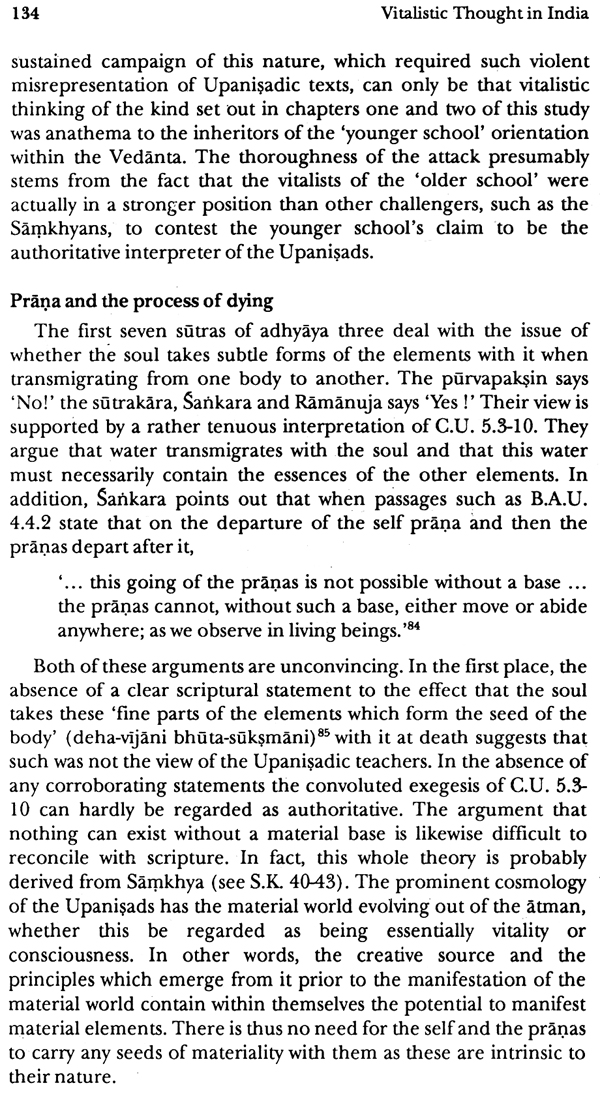

| Item Code: | NAU587 |

| Author: | Peter Connolly |

| Publisher: | Sri Satguru Publications |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 1992 |

| ISBN: | 8170303486 |

| Pages: | 218 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 370 gm |

Book Description

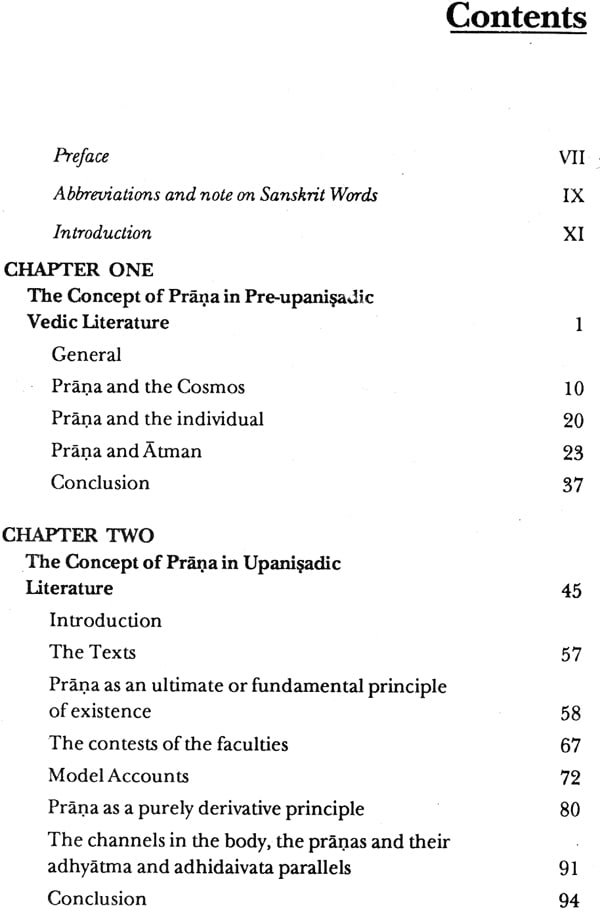

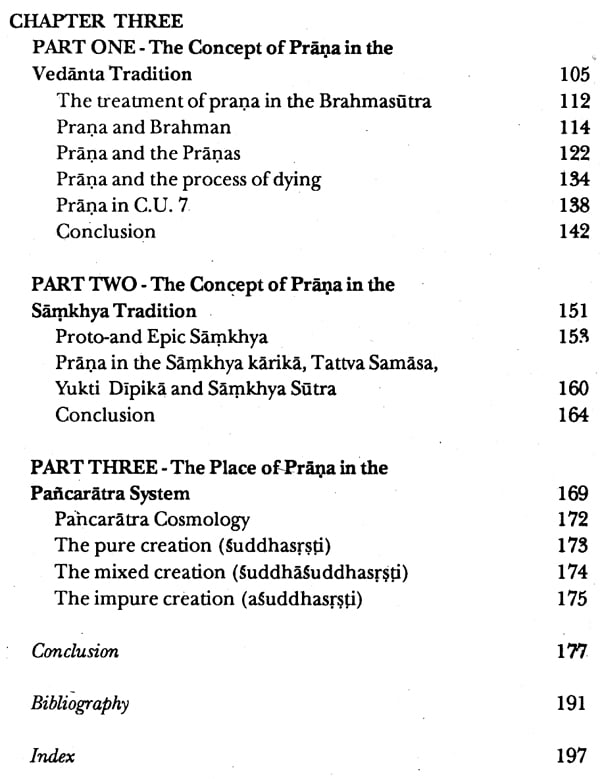

This study emerged from an earlier interest of the author in the subtle body (suksma or linga sarira) as found in the sacred literature of India. Descriptions of the subtle body vary from tradition to tradition and from text to text. The study divides into three major sections. The first deals with the evolution of the prang concept in pre-Upanisadic, Vedic literature, the second with its treatment in the Upanisads, whilst the third examines its place in the world-views of three influential religio-philosophical traditions which claim to be in accord with the teaching of the Veda, Vedanta, Samkhya and Pancaratra.

Peter Connolly was born on 22 Nov-ember in Chorley, Lancashire, England. Despite being educated at Roman Catholic school he freed himself of involvement with that faith as teenager. He nevertheless retained an interest in religion, both in term of what it had to offer individuals and how it influenced human societies. He took his BA, MA and Ph.D degrees in the department of religious studies, University of Lancaster, England, specializing in Indian Religious Traditions. In 1980 Dr. Connolly took up a lectureship in Religious Studies at the West Sussex Institute of Higher Education, Chichester, England, where he still teaches. He has published a number of articles on Buddhism, Yoga and Religious Education and two school text books on Buddhism. He is presently conducting re-search into the psychology of religion. Dr. Connolly is married and has two daughters.

This work is a revised version of my thesis 'The Concept of Prana in the Literature of the Veda and its Development in the Vedanta, Sarnkhya and Pancaratra Traditions', for which I was awarded the 164 degree Doctor of Philosophy by the University of Lancaster, England. Consequently much of it is quite technical in nature. The general reader may therefore find it useful to read the 169 introduction, conclusion and chapter summaries before working through the text proper. The conversion of the thesis into a book could not have taken 175 place without the assistance of others. I would particularly like to express my appreciation to the Research and Publications 1'77 Committee of the West Sussex Institute of Higher Education for providing a grant to cover the cost of retyping and to Karen Woods, Sarah Pollard and Tracy Bruton for doing the work. I am also grateful to Dr. Andrew Rawlinson and Dr. David Smith of Lancaster University for their help and guidance whilst I was a graduate student. If other students of Indian religion find this work useful in the course of their own investigations I will consider my efforts to have been worthwhile. This book is dedicated to my Mother and Father, who helped me return to education after a period of youthful disenchantment and rebellion.

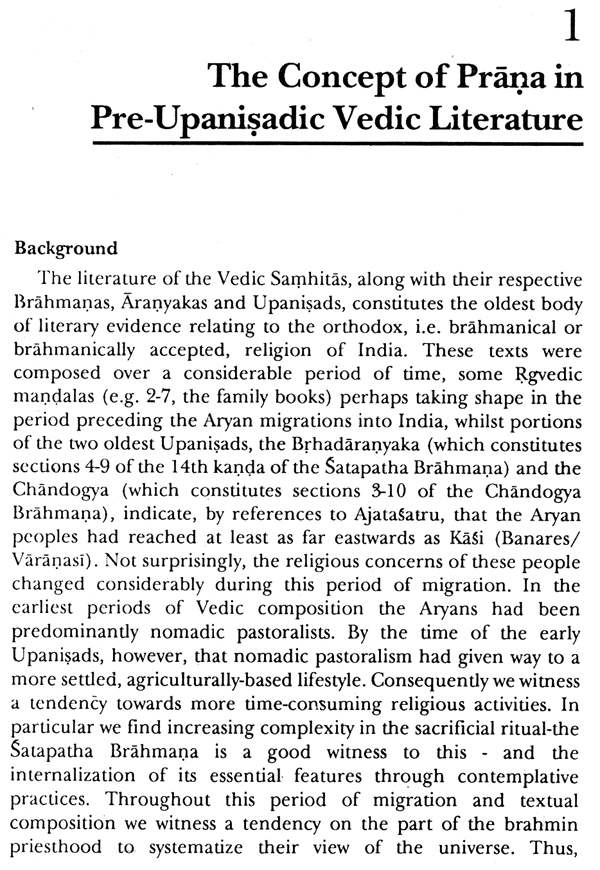

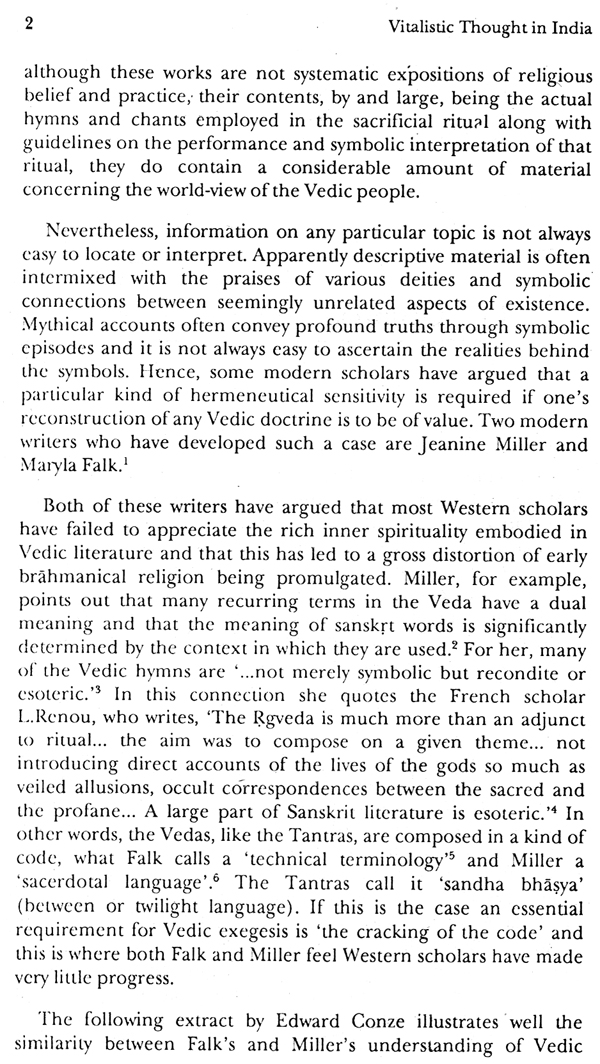

This study emerged from an earlier interest of mine in the subtle body (suksma or linga garira) as found in the sacred literature of India. Descriptions of the subtle body vary from tradition to tradition and from text to text. The reasons for the variations are not, however, readily apparent. One thing which did become clear as I examined the material relevant to this issue was that in some accounts, e.g. those found in Vedanta literature, prana (breath, vitality) was a prominent component whilst in others, e.g. those found in Samkhya literature, it found no place at all. It was this discrepancy, perhaps more than any other factor, which led me to focus on the development of the pra.na. concept. I was hoping thereby to go some way towards adducing reasons for the existence of two quite different accounts of an entity which performed an almost identical function in the different systems. The following discussion offers what I hope is a convincing answer to that problem and one which will constitute a working base for further elucidation of material relevant to this issue.

The study divides into three major sections. The first deals with the evolution of the pra.na concept in pre-Upanisadic Vedic literature, the second with its treatment in the Upanisads, whilst the third examines its place in the world-views of three influential religio-philosophical traditions which claim to be in accord with the teaching of the Veda: Vedanta, Samkhya and Pancaratra. The Vedanta and Samkhya systems are two of, if not the two molt influential, indigenous world-views in Indian culture. The great epic Mahabharata is permeated with concepts from both traditions. So too are those great compendia of mythology, cosmology and ethical guidance, the Puranas. Similarly, the various Vaisnava, Saiva and Sakta sects all display the influence of one or both these systems in the construction of their soteriological and cosmological doctrines.

In the modern period, due to the efforts of groups such as the Ramakrishna mission and the Arya Samaj,' Vedanta has been presented to India and the world as India's great philosophical heritage, whilst Samkhya has become virtually redundant as an independent system. Even so, its influence is felt everywhere, even in the Vedanta tradition which, like Rome did to Carthage, has eliminated it as a competitor. The choice of Pancaratra as the third system for investigation was largely determined by the fact that it is the most ancient Vaisnava tradition and boasts a considerable and influential literature. Its philosophical basis is a reasonably clear synthesis of Vedantic and Samkhyan thought whilst its overall world-view is dominated by the most pervasive and influential force in Indian religious life: bhakti, the attempt to experience complete devotion and surrender to a personal god. It thus seemed an ideal system for inclusion into this study. Other possible contenders were the Saiva systems of Kasmir which, in varying degrees, represent syntheses of Vedanta and Samkhya teachings and the later Natha Yoga tradition which emerged out of what might be called 'the tantric ferment' of medieval Bengal. However, neither could boast the same antiquity as the Paticaratra and would therefore be less illuminating with regard to the earlier career of the prana concept. Nevertheless, they contain much material relevant to this study and should provide fertile pastures for similar investigations in the future.

**Contents and Sample Pages**