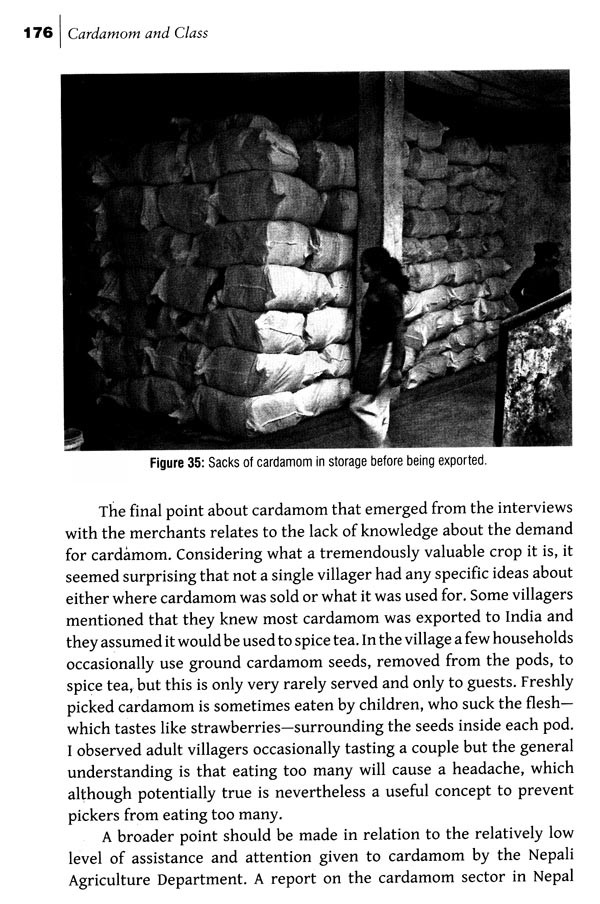

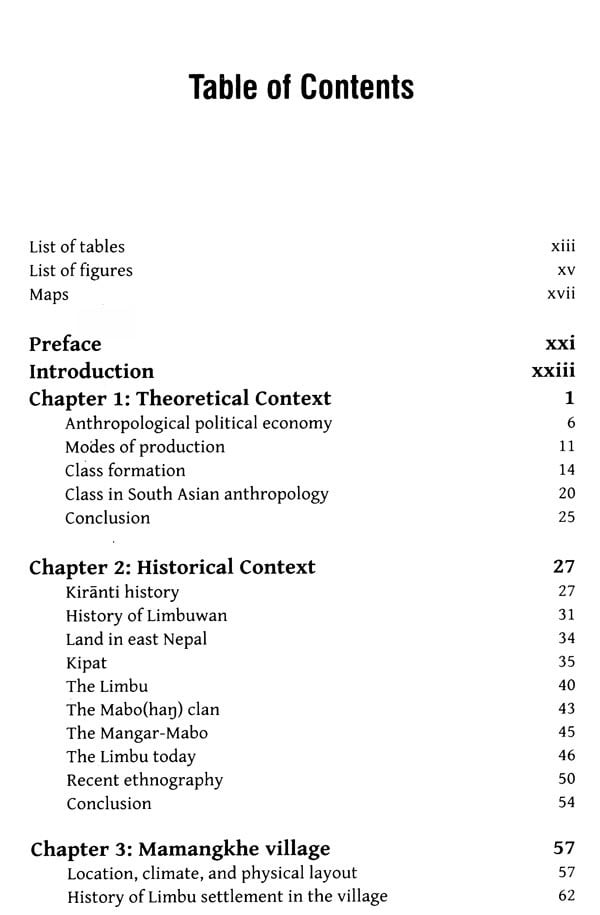

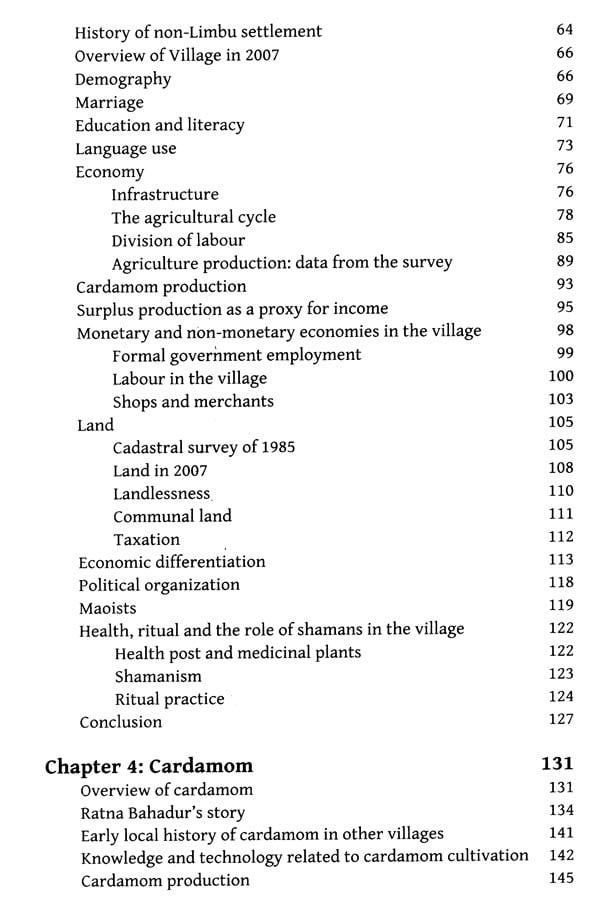

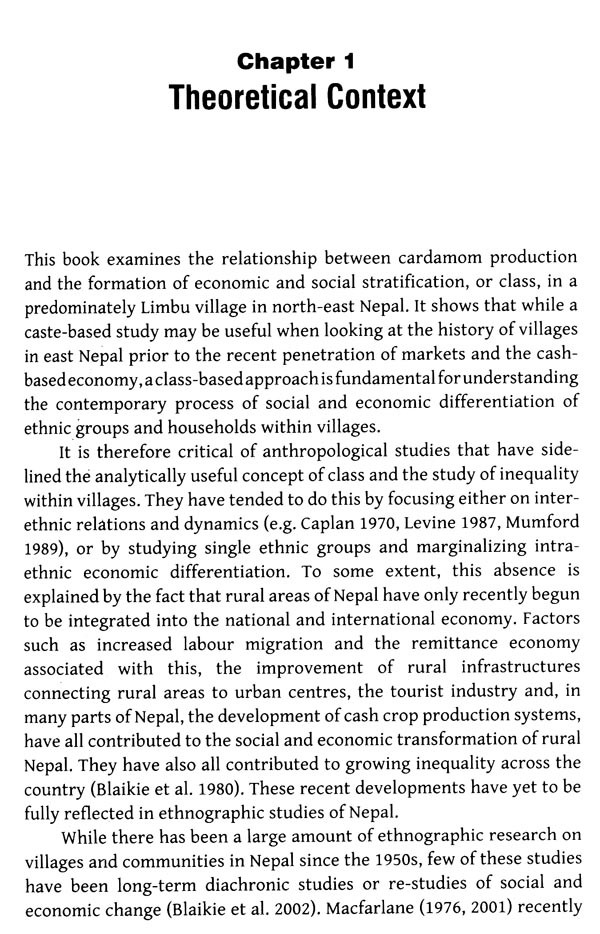

About the Book Cardamom and Class investigates the history of economic differentiation in a Limbu village in east Nepal, By examining three historically overlapping productive processes subsistence agriculture, cardamom cultivation, and international migration this book shows how each productive process has contributed in different ways to the acceleration of economic differentiation and rural class formation. In particular it focuses on cardamom, introduced to the village in 1968, which as a high value cash-crop has provided a means to transform significantly the lives of a large section of Limbu society.

Despite the increased integration of the village with a national and global market, the confinued existence of Limbu language and cultural practises emphasizes the active role villagers have played in shaping their current condition.

About the Author lan Carlos Fitzpatrick is an anthropologist and ethnobotanist, currently working in the UK as a campaigner, researcher and writer on economic and environmental issues.

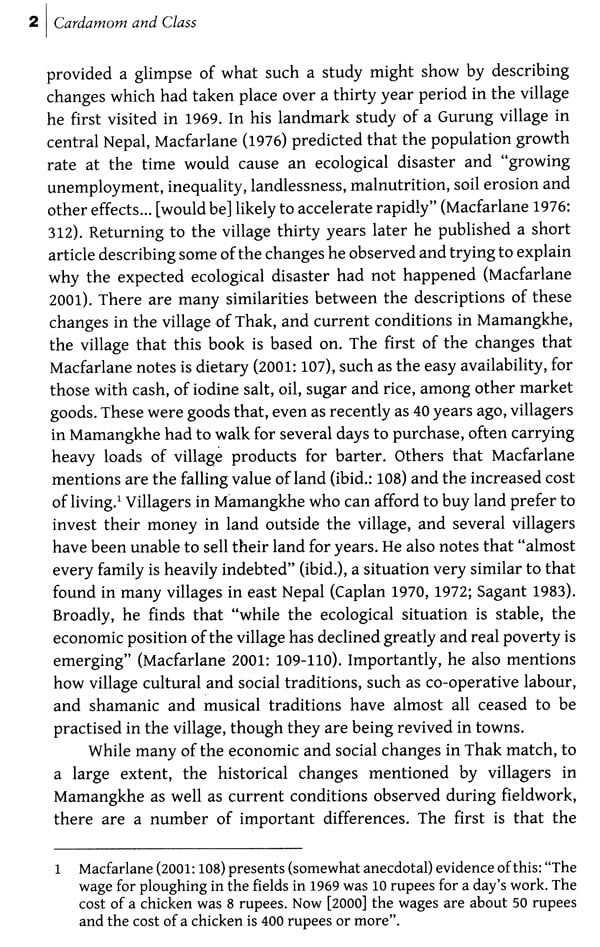

Preface Class, as a topic of academic study, has become increasingly unfashionable in the academy. This is perhaps surprising in the study of Nepal, where Marxist-inspired ideologies dominate both political parties and the universities. Older works, such as Seddon, Blaikie, and Cameron's Peasants and Workers in Nepal (Seddon et al. 1979) tried to study class formation, but where are their modern successors?

When anthropologists have tackled class, it is, paradoxically, class as status group, class as defined by consumption patterns. In the Nepalese context, the leading and much-cited work in this genre is Mark Liechty's Suitably Modern: Making Middle-Class Culture in a New Consumer Society (Liechty 2003). This is a fine and, in the Nepalese context, pathbreaking work, but it does not broach the question of the production of middle-class identity in schools, offices, factories, and other workplaces. Nor does it ask the classic questions about ownership, wealth, and land that underlie the emergence of class.

It is therefore particularly welcome that a young anthropologist should tackle the emergence of class in a rural setting using the quantitative survey methods necessary for any economic anthropology, but also participant observation and close-up, hands-on fieldwork (both literal and metaphorical). Ian Fitzpatrick was also accomplished in both local languages (Nepali and Limbu). The Limbus are lucky to have attracted an ethnographer with such linguistic skills.

Cardamom is one of the few cash crops that, if a peasant works hard and has a reasonable run of luck, can lead to serious accumulation of wealth in a relatively small number of years.

Introduction There is a considerable degree of continuity between the Nepal that emerged from the Gorkha conquest in the late 1700s and the Nepal of today. The economy continues to be largely subsistence-based and 86% of the population located in rural areas (CBS 2007). Yet Nepal has been affected by its rapid incorporation into a global economy through a number of processes, including: the increased dependence on a national and international market economy which has penetrated even the remotest corners of the country; a large increase in both population and land under cultivation; an increased proportion of the working population of Nepal becoming involved in foreign labour migration; and the transformation of cultural values through a set of economic and social conditions associated with wealth, prosperity, 'modernity' and urban Nepal. These processes have provided many villages and households across Nepal with a means (and desire) to change their economic and social conditions. The integration of rural Nepal with an urban-based market economy has provided subsistence farmers with the opportunity of supplementing their income with market-oriented production of food and goods. Such production and trading of goods has, of course, taken place for hundreds of years, but the recent penetration of the market has facilitated the distribution of products and linked more directly than ever before the fate of the remote rural village with that of the global market. This dependence on the global market, for both goods and labour opportunities, has made rural households considerably more vulnerable to the fluctuations of the global economy.

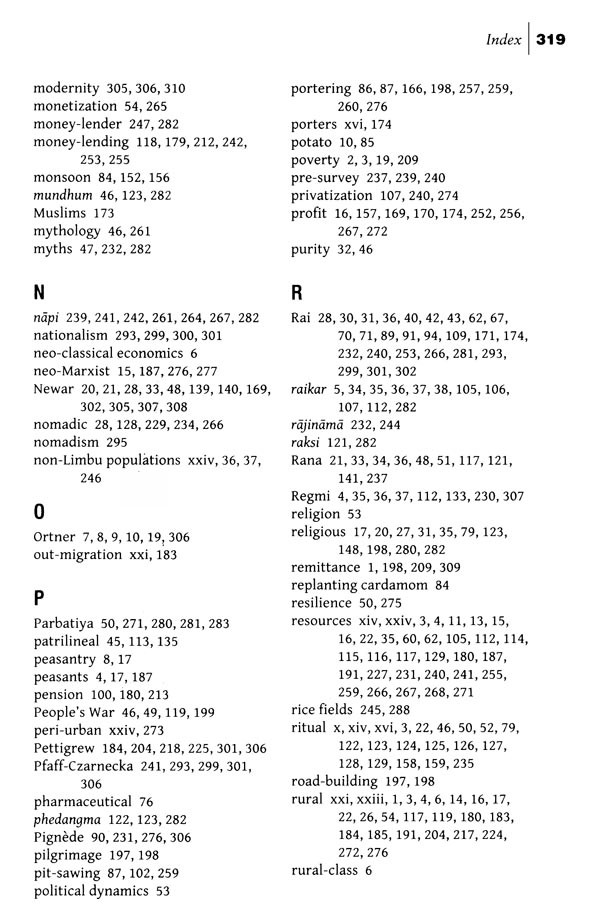

**Contents and Sample Pages**