The Complete Pancatantra: Sanskrit Text with English Translation

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAL574 |

| Author: | Dr. Naveen Kumar Jha |

| Publisher: | J.P. Publishing House |

| Language: | Sanskrit Text With English Translation |

| Edition: | 2021 |

| ISBN: | 9788193077962 |

| Pages: | 824 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 830 gm |

Book Description

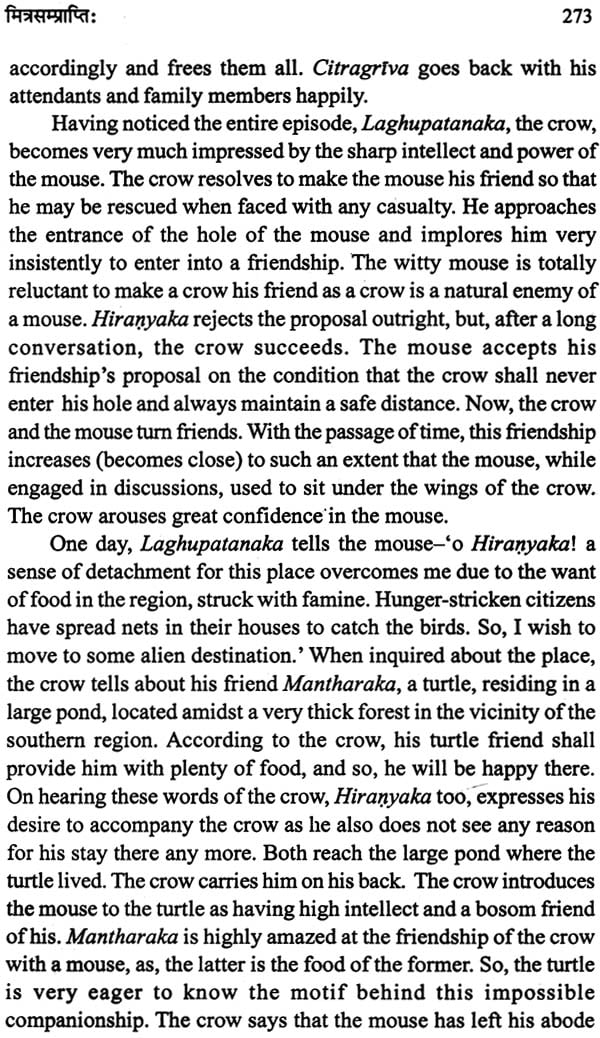

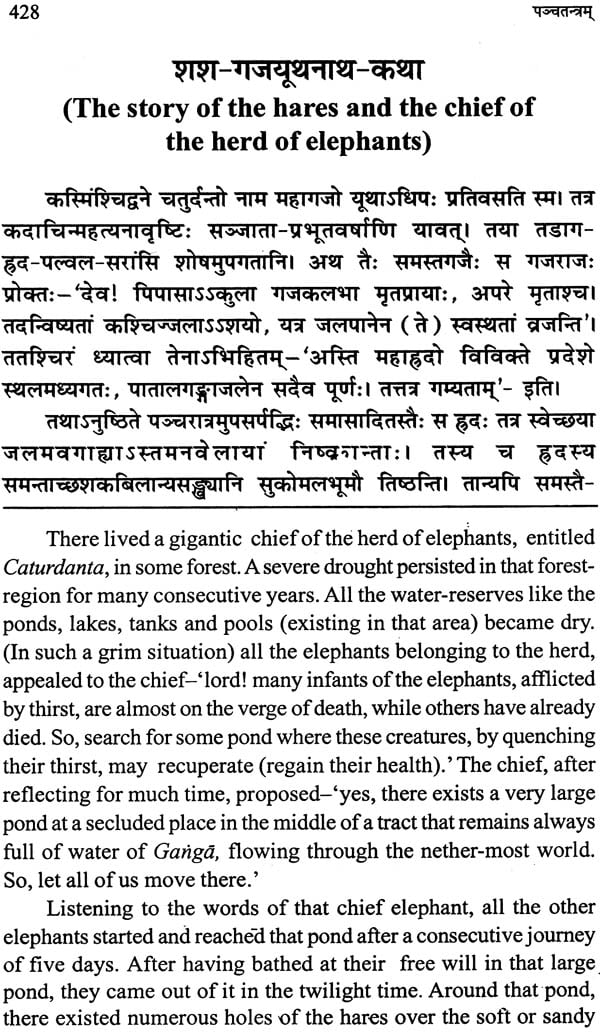

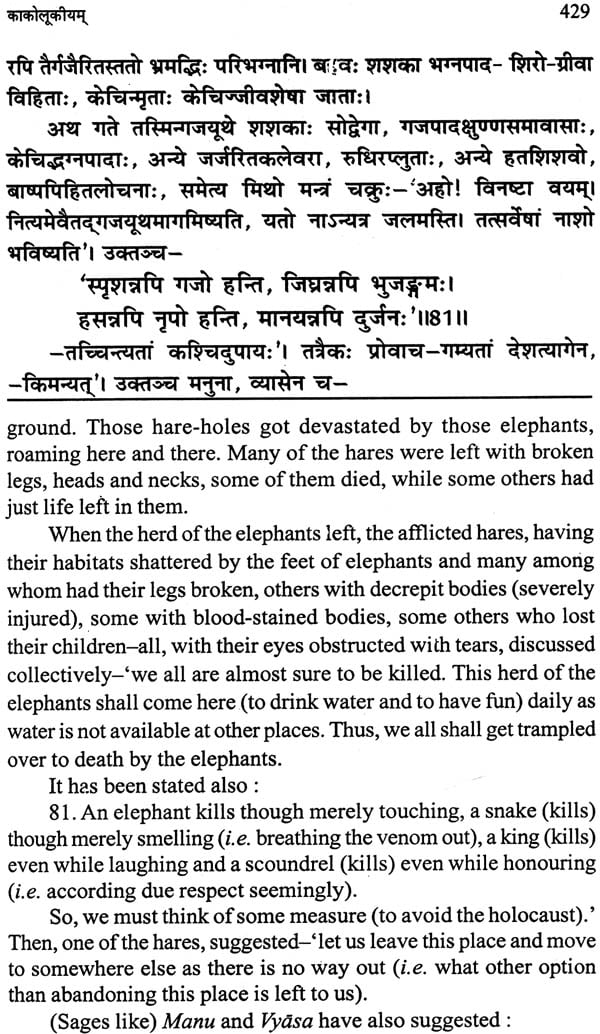

Pt Hazari Prasad Dwidedi, the accomplished author and doyen of Hindi- Sanskrit critics, had once rightly remarked that the Bhagavadgita and the Meghaduta are like the bells in the temple of lord Visvanatha that are invariably struck at least once in life-time by every visitor (Meghaduta: Ek Purani kahani).In the opinion of the present authors this enumeration would have emerged more compact as well as balanced, had he incorporated the Pancatantra also. Truly, it is only the indomitable life-spirit and the unconquer able inner-strength of a text that it attract the minds of the readers in all ages.

On the basis of its content, the Pancatantra of Srivisnu sarman can not regarded as a textbook of political science in the modern sense of the term. But, undoubtedly, a good part of it is related to politics. We find the author making a free and deliberate attempt to free politics from the influence of religion and morality at the risk of being labelled sometimes as ‘Machievelliam’ and preaching craft and deceit. The text was intended mainly for the instruction and training of the nascent king and ministers in the art of governance. To achieve his purpose and to have a broader reach, the author of this classic has not hesitated in digesting the views of his predecessors, Viz. Kautilya, kamandaka, Sukra and Vedavyasa to name a few. The reason for it being that the prevalent form of government was monarchy. But, apart from its political purport, Pancatantra is about human concerns and tendencies to evaluate one’s well-being by comparing it with that of another, It deals with moral instructions, human tendencies, weaknesses, desire to flourish and, above all, being pragmatic in worldly pursuits. In this age of speed and restlessness, unquenchable desire for having plenty of riches at all costs, and, utter immorality, the intent, intent, content and implication of this timeless text bespeak its relevance and indispensability.

The interesting conversations that occur between the animals –some-times between a jackal and a bull, or jackal and a lion, the crow and the owl, the monkey and the crocodile-concern the duties of human being in general and the kings and his ministers or political strategists in particular. The power of these debates, if scrutinized, have over the centuries, generated much moral and political deliberations. As the Pancatantra forms the pare of the extensive literature in political and moral philosophy on duty-based reasoning, as it possesses the power of stirring the minds event today, it is undoubtedly justified to review the work even in this post-modern age. If the tales of this are analysed with a fresh and pragmatic insight, it can still do miracles in shaping individuals and societies as well. Stories originate from the popular or public life, so, a retrospection of these popular tales as symbolic narratives in today’s context would prove a timely endeavour. This, being the firm belief of the present authors, has served as an inspiring force behind this edition.

At a time when civilization is in peril and efforts of social reconstruction are on, it is wise to know what the seers of the past have said on the perennial and deepest problems of thought and life. The questions of the nature and destiny of man, the purpose of society, its relation to the individual are always pertinent and intimate to each one of us. As human being is teachable, so, by a sympathetic study of the past gropings and stumbling of mankind, he can avoid at least its repitition.

It is not without misgiving that one ventures to render into English, one of the most translated works ever throughout the world. But the historical, political and sententious importance of this text, as forming a bridge between the ancient Indian philosophy of life, politics and practical wisdom, and the fully developed political thoughts and concerns of today, emboldens one to such an attempt. Reason for taking up the work concerns our long cherished wish. To grasp the secrets taught in the Pacatantra thoroughly, one needs a knowledge of the whole field of ancient Indian statecraft and an acumen to judge judge its purport. Such being the nature of this text, those with our limitations of knowledge, can not presume to be able to do any justice to its merits and that in what is called a ‘preface’.

Sir William Jones (1746-94), the father of Indology and a linguistic genius, in his discourse on the Hindus, observed that they said have laid claim to three inventions-the game of chess, the decimal scale of notation and the mode of instructing by apologues. This observation stands true as India has been a land of cheerful people where, in the words of A.L. Basham ‘each finding a niche in a complex and slowly evolving social system, reached a higher level of kindliness and gentleness in their mutual relationships than any other nation of antiquity.’ Prior to this statement, he records his impression regarding the jovial and care-free attitude of Indians in following words:

‘The European student who concentrates on religious texts of a certain type may well gain the impression that ancient India was a land of “life negating” ascetics, imposing their gloomy and sterile ideas upon the trusting millions who were their lay followers. The fallacy of this impression is quite evident from the secular literature, sculpture and painting of the time. The average Indian, though he might pay a lip-service to the service to the ascetic and respect his ideals, did not find life a vale of tears from which to escape at all costs; rather he was willing to accept the world as he found it, and to extract what happiness he could from it.’[The wonder that was India, Intro P.9]

This liveliness of ancient is well-expressed through a long tradition of the timeless jewels of the myths, legends, fairy tales and fables-which survive in the rich and abundant store-house of Sanskrit literature. The ancient sages and poets of this nation invested the didactic themes and traditional beliefs with beautiful symbolism and used them as mediums of profound ethical and moral suggestions. The most striking feature of ancient Indian civilization has been the element of humanity combined with a sense of duty and practicality. And this quality has been well-expressed through the colossal Sanskrit literature ecompassing a wide range of sententious apologues and fables and fairy tales. There also exists an extensive literature in political and moral philosophy, that tends to reflect the most insightful meditation and the profound reflections on human destiny. This has been the central value, marking the genre from it’s beginning, and a source of incomparable pleasure and sustenance to those connoeisseurs with the insight and cultural training to appreciate and learn from it.

Prior to an introduction to the Pncatantra, we deem it proper to precede with the strong back-ground it had. Sanskrit language is the repertory of an extensive literature having a perennial source in its antiquity. It has an undecayed and continued tradition of fables, folk-tales, fairy-tales and sententious narrative (Katha, Akhyanas) that left indelible impression not only on Indian literature but has also immensely influenced word- literature. The three great religious sects of India, viz. Vedic, Jaina and Buddhist- have for the wide dissemination of their tenets, used numerous fables and narratives. These sects own huge treasure of fables and parables where the ultimate motif is not only to expound the religious purports of these sects but also to throw ample light on the importance wisdom. The timeless treatises, belonging to this genre, verily represent the Sanskrit literature on ethics and jurisprudence and are rooted deep in antiquity.

That branch of didactic literature is called ‘fable’ which comprises of little, cheerful and sententious stories and whose characters are often animals. The word fable comes from the latin word fabula which once was employed to mean any kind of story. But, gradually it came to mean a very special kind of story. The didactic sub-division of fictional narrative is termed as ‘fable’, which is ruled by an intellectual and moral impulse and it tends towards brevity. It is a narration intended to enforce useful truth, especially one in which animals speak and act like human being. The characters teach lessons which can be used in every one’s daily life, since their actions are so much like those of human beings, the reader of the fable usually does not have to figure out for himself what the lesson is. Often given at the end of the fable under the title of ‘Moral’. So, unlike a folk-tale, it has a moral that is woven into the story and often explicitly formulated at the end.

Fables have very ancient roots in the literary and religious traditions of India, china, Japan and many other South East Asian countries. The western fable-tradition began with tales ascribed to Aesop, it flourished in the middle ages, reached a high point in 17th century in France in the work of jean de La Fontaine and found a new audience in the 19th century with the rise of children’s literature.

The most important feature of beast-fables (the story on the toungue of animals) is the use of a frame-story with other stories fitted in it. This pattern was freely adopted in The Arabian Nights, chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Boccacio’s Decameron, The Earthly Paradise of William Morris, in Longfellow’s Tales of a way-side inn. So, its influence has been world-wide and the echo of which can be heard anywhere.

Incidentally, having a glance upon some other forms of stories, would not be out of context. There are other kinds of stories which are much like the fables but which are not true fables. One of these is Parable which very often appears in the Holy Bible. A Parable is a story related to teach a lesson of the religious nature, such as the Parable of lost sheep. Another kind of story much like the fable is beast-epic, in which characters are always animals. The beast-epic seldom tries to teach a lesson, instead, it makes fun of people and the way they behave. The story of ‘Reynard the Fox’ and ‘Chicken little’ are the best known best epics English. A common prose form is called Allegory. It is a tale either in prose or verse which bears a double meaning Behind the simple tale, a great truth or moral lesson is necessarily perceived there in an allegory which may be in the form of a written document or an oral or visual expression where symbolic figures, objects and actions are used to convey truths or generalization about human conduct or experience. Characters often personify abstract concepts or types and the action of the narrative usually stands for something not explicitly stated. Symbolic allegories, in which characters may also have an identity apart from the message they convey, have frequently been used to represent political and historical situations and have long been popular as vehicles for satire.