Evolution of The Garbhadhatu Mandala

Book Specification

| Item Code: | IDK866 |

| Author: | Ulrich Mammitzsch |

| Publisher: | Aditya Prakashan |

| Edition: | 1991 |

| ISBN: | 8185179700 |

| Pages: | 369 |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 11.0" X 8.7" |

Book Description

This book is the first in English to detail the splendid images the imago mundi of Shingon/Mantrayana in all its profundity. This profundity is difficult to capture in words. The teachings are so profound that they are best expressed in painting.

It is a systematic study of the evolution of the Garbhadhatu mandala in china and Japan. It develops in the various in the various chapter of the root tantra the Dainichikyo/Mahavariocana-sutra in its two main commentaries, in it four ritual handbooks in its iconographic sketches of Subhakara-simha and finally its culmination in the Genzu version. The Genzu is the best known version and is considered in Japan to be the Gabhadhatu mandala. The author begins with a general description of a mandala a definition of the term mandala its component yards and deities/son and its various versions.

The second chapter is a succinct summary of the Dainichikyo/Mahavairocana-sutra. The contents of all the 31 chapters and the five supplementary chapters 32-36 are given. The third chapter summaries the four ritual handbooks translated by Subhakara-simha and by Fa-chuan. They were used in the eight century. Seven versions of the mandala (A-G) in the basic Tantra, the acarya-transmitted mandala H in the commentaries mandalas I-L of the ritual handbooks and mandalas M,N in the iconographic sketches; are detailed at length in the forth chapter as the fourteen pre-Genzu versions .

The fifth chapter is a detailed study of the iconology and symbolism of the yards and of their individual deities in the yards and the Genzu version. Major Japanese works that describe the Genzu at length are listed at the end. The book concludes with a general symbolism of the mandala: a manifestation of Mahavai-rocana whose compassion are decent into the world of form and with the process of Kajil adhisthana make the acolyte rise above this world of distinctions.

The book is a poignant testimony to the life-long studies of Prof. Ulrich Mammitzsch who passed away on 19 November 1990 into the ethereal domains of the mandala.

Ulrich Hans Richard Mammitzsch (1935-1990) came from Chinese history to Buddhist art. In exploring the mandalas he established both method and workable framework for these studies by focusing on the Garbhadhatu mandala. He looked at the syncretic Shinto-Buddhist and Tibetan mandalas. Did his Ph.D from the University of Hawaii in 1961-68. Worked at the national Taiwan University and the Academia Sinica on later Ming eunuchs and the factional strife at the Imperial Chinese court. Taught at the universities of Hawaii, Western Washington, California/ Berkeley, Chicago, Asia and Meiji Universities at Tokyo. Articles on Chinese government. Translated Dietrich Seckel's Buddhist Art of East Asia. Since 1983, several papers on various aspects of the mandala. Ulrich was renowned world wide for his work in the iconology of East Asian Buddhism. His bibliography is extensive, but during much of the last decade of his life he was deeply engrossed in the study of the iconography of esoteric Buddhism, particularly of the mandala the symbolic diagrams of the cosmos.

As I pen these lines, Prof Ulrich Mammitzsch is no more. The light that warmed with joy of erudition is cold. The links of enchantment of many hours and days spent in discussions and dialogues are still there with me: the endless dynasty of our delight. Let me tell his tale in the long strain of doings on his storm-bound road of life.

Ulrich was born in Rodishain in the Harz Mountains of Germany to which he wanted to return some day. He had degrees from the university of Humburg, Southern Illinois University and the University of Hawaii. He come to western in 1971 and was the specialist in the Department of Liberal Studies in studies. He served as director of the East Asian Studies Program.

Ulrich was renowned world wide for his work in the iconology of East Asian Buddhism. His bibliography is too extensive to reproduce here, but during much of the last decade of his life he was deeply engrossed in the study of the iconography of esoteric Buddhism, particularly of the mandala the symbolic and meditation. Through now mostly surviving in Japanese temples and monasteries, Ulrich traced particular mandala back to early medieval Chinese prototypes and to the Indian metaphysical principle upon which both the Japanese and Chinese mandala were construed. Ulrich had completed a major work on the Genzu version of the Garbhadhatu mandala being published in this volume. He had already embarked in further major researches. He had also recently completed a translation of Dietrich Seckel's Buddhist Art of East Asia, published by western Washington University and had collaborated in a new translation of Johan Huizinga's Autumn of the Middle Ages, forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press.

Ulrich's great strength came from his wide learning in the history and culture of East Asian civilizations which was joined to his mastery of European and American culture. His life through outwardly calm had highly dramatic aspects. His youth was made difficult by the imprisonment of his father by the Nazis. Once he was trapped in a cave where his family had family had taken shelter from American bombers, but the bombs collapsed the mouth of the cave. He escaped from the communists twice, once as a boy at the end of world war II when he and his sisters borrowed a horse from the local nobleman and fled with a few possessions. His second escape was in 1957 when, as a student in the East, he was accused of disloyalty to the party (he had refused to vote in an election which, as a student in the East, he was accused of disloyalty to the party (he had refused to vote in an election which had only one candidate). He came to the few on a train pretending to be a local commuter. He always referred to this event as his flight to freedom wonderful sense of humor and his warm sociability simply cannot be replaced. He was a skilled poker and racquet-ball players as many old hands learned at their own expense. Though Ulrich never married, he loved children and several children of the faculty called him Uncle and count themselves his survivors".

This study attempts to interpret the so-called Genzu version of the Garbhadhatu mandala in Japan. This Genzu version is not only the best known version of the Garbhadhatu mandala, it is also generally considered in Japan to be the Garbhadhatu mandala-which constitute the imago mundi of the Shingon (mantra) school of Japanese Buddhism, i.e., they are interpreted in Japan as a visual representation of the Cosmic Buddha Vairocana under the aspects of his principle (ri) and wisdom (chi) respectively. Both mandalas the sutras they are based on, and the ritual and yogic practices linked to them evolved separately until they were brought together and interpreted in the manner inherited and continued this tradition of the dual mandalas.

Of the two mandalas, the Vajradhatu mandala is also well known outside of Japan. It has a relatively stable iconographic tradition (the recent discoveries of a number of variant types in the Ladakh region notwithstanding). The Garbhadhatu mandala, on the other hand is not only virtually unknown outside if Japan, it has also remained an enigma. Through based on a particular tantric text the Mahavairocana-sutra this mandala is not merely a pictorial rendition of any particular of the several mandalas described in this text. It should therefore be best understood as designed by a Chinese acarya whose intentions in fashioning this mandala are unknown. Efforts to fathom these intentions remain problematical since the acarya not only left no comments on this particular subject but new images of his own design for which no textual and iconographic sources) can be found. This has left many facets of this mandala open to different interpretations and this fact in turn, has led to continuous efforts to unlock its secrets throughout its history in Japan. The Japanese literature on this subject is therefore vast and continues to grow steadily. This essay looks at the Genzu Garbhadhatu Mandala and continues to grow steadily. This essay looks at the Genzu Garbhadhatu Mandala in the light of both the textual evidence and the ongoing search for unlocking its secrets. No dramatically new evidence or interpretations are therefore offered but of our present understanding of its sources and functions.

In Japan there has recently been a renewed been a renewed interest in Buddhist art in general and in mandalas in Particular (including the Genzu version). The result of all this attention has been a "mandalas boom" which has spawned a number of publications and exhibitions. These have not only made the treasure of Japanese mandalas more accessible to a wider Japanese and non-Japanese public, but have also put at our disposal a plethora of new material for studying these mandalas.

Among the most important events which were part of this "mandala boom" were the publication of the Den Shingon-in Ryokai Mandala (1977) of this pair of mandalas (which includes the Garbhadhatu mandala) in a series of spectacular color photographs by Ishimoto Yasuhiro presenting heretofore-unavailable details and an introductory essay by Yamamoto Chikyo and Manabe Shunsho. Another important impulse for the "mandala boom" came from the discovery of a number of early medieval Tibetan mandalas in the Ladakh region of NW India-which provide a most welcome opportunity to sample variants of Vajradhatu mandalas heretofore unknown in Japan. The photo exhibition of these finds not only attracted large audiences but provided also a favorable climate for scholarly studies on the subject which have not only significantly advanced our understanding of esoteric Buddhism, its and its mandalas but have also laid the foundation and established direction for future inquires.

Modern Japanese scholarship on mandalas had evolved since the Meiji period. This scholarship combines the stimulus from modern Western scholarship with a longstanding tradition of scholar-monks whose labours have left a wealth of materials which is now slowly becoming available to a wider academic and non-academic public in Japan and abroad.

The basic texts for understanding the Genzu Garbhadhatu mandala are the Dainichikyo (hereinafter, DNK) and its two commentaries by Sabhakarasimha, the Dainichikyosho (hereinafter DNKS) and Dainichikyogishaku (hereinafter DNKGS). There are also four ritual handbook used in the Shingon tradition which are published in volume 18 the Taisho edition.

| Preface | 7 | |

| Chapter | ||

| 1 | Introduction | 9 |

| General description of a mandala | 9 | |

| Towards a definition of the term mandala | 15 | |

| Versions of the mandala | 25 | |

| 2 | Summary of the DNK, ch 1-36 | 30 |

| 3 | The four ritual handbooks | 69 |

| 4 | The pre-Genzu mandalas | 80 |

| mandala DNK | ||

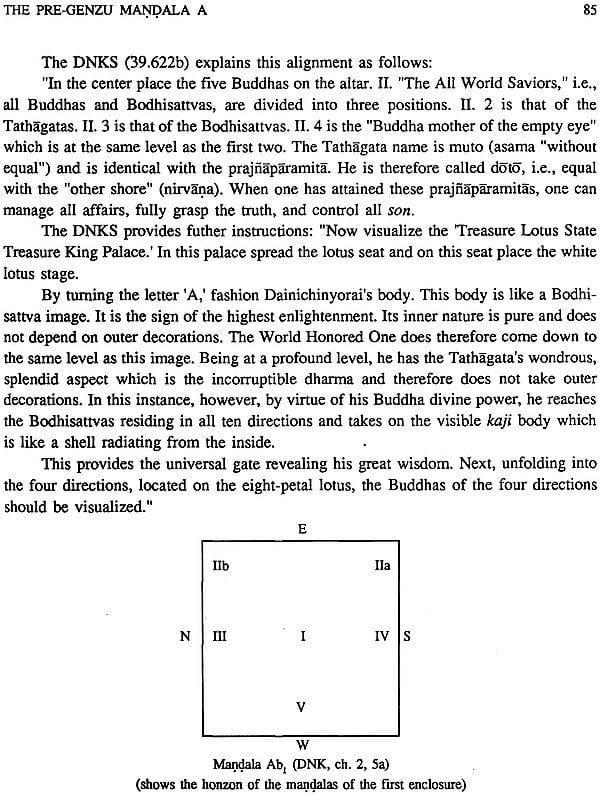

| A | Ch. 2 (Nyu mandara guen Shingon) 18.4-12 | 81 |

| B | Ch. 4 (Futsu Shingon zo) 18.13-14 | 104 |

| C | Ch. 8 (Tenjirin mandara gyo) 18.15ab | 109 |

| D | Ch. 9 (Mitsu yin) 18.16-17 | 114 |

| E | Ch. 11 (Himitsu mandara ) 18.17-19 | 119 |

| F | Ch. 13 (Nyu himitsu mandara) 18.19-20 | 128 |

| G | Ch. 14 (Himitsu hachi yin) 18.21-22 | 131 |

| Commentaries (DNKS, DNKYGY) | ||

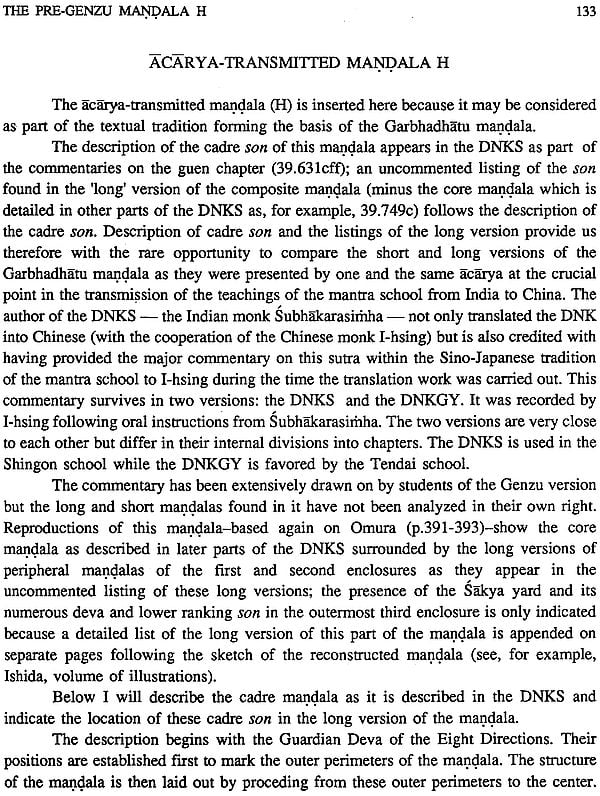

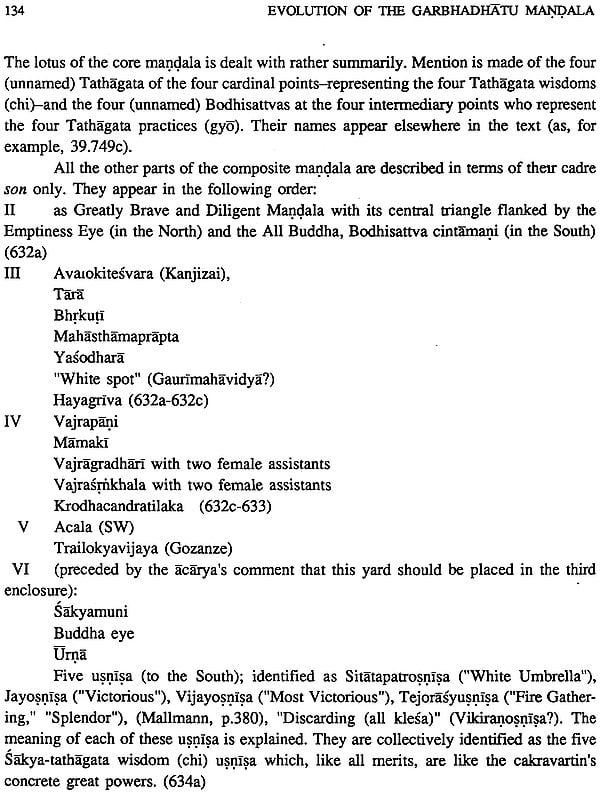

| H | Acarya-transmitted mandala | 133 |

| (described in the two commentaries ) | ||

| Ritual handbooks | ||

| I | Sho-daiki T 850 (18.64a-90b) Subhakara-simha | 141 |

| J | KO-daiki T 851(18.90b-108b) Subhkara-simha | 141 |

| K | Gempoji-ki T 852 (18.127b-143c) Fa-ch uan disciple of Hui-ko | 141 |

| L | Seiryuji-giki T 853 Fa-chuan | 141 |

| Sketch-books | ||

| M | TZZZ | 142 |

| N | TZKZY | 146 |

| Summary of the 14 pre-Genzu mandala | 148 | |

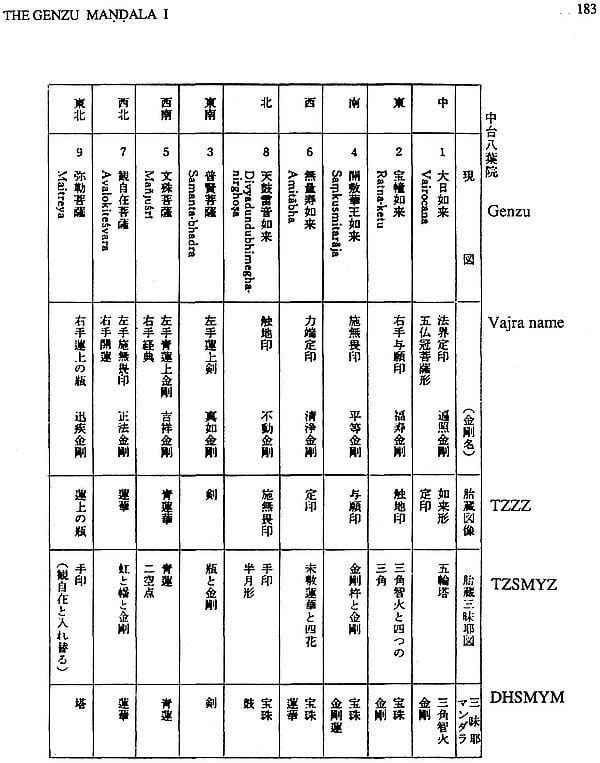

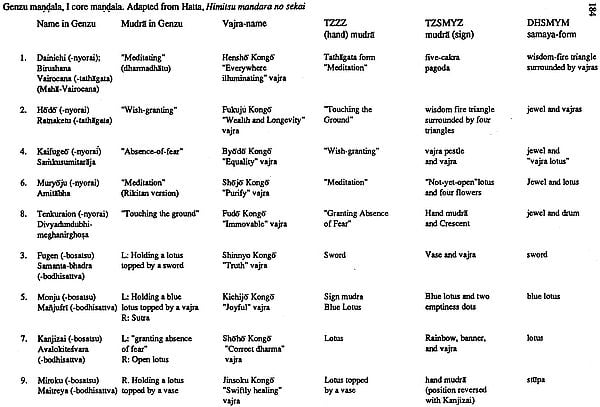

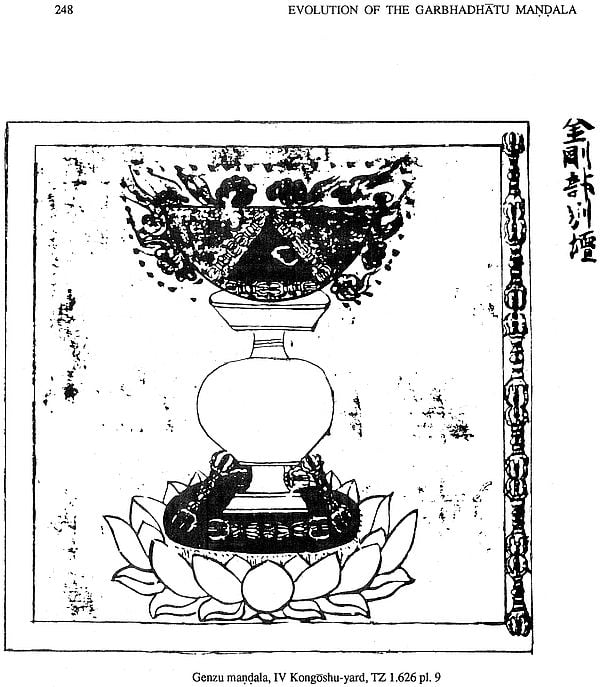

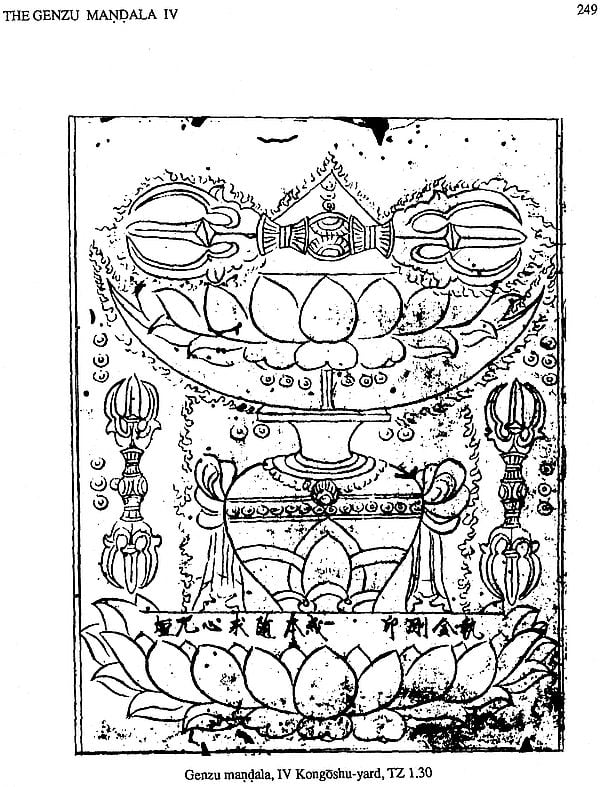

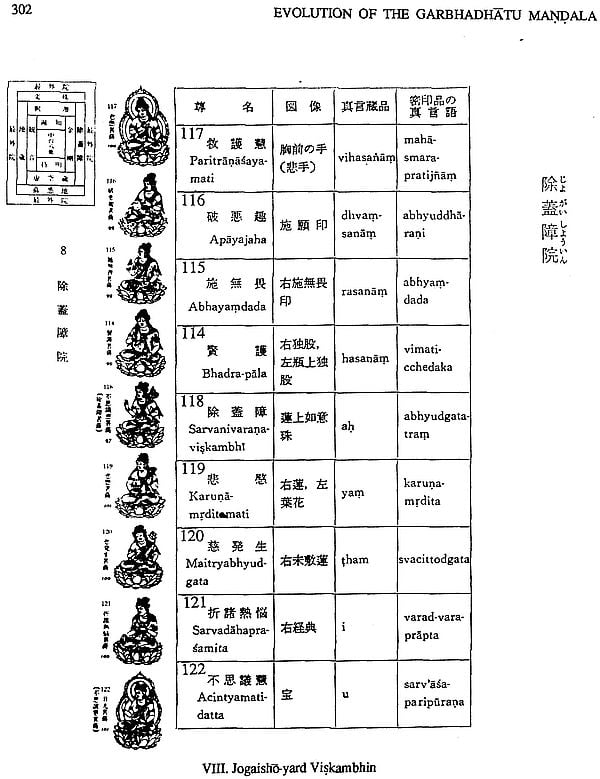

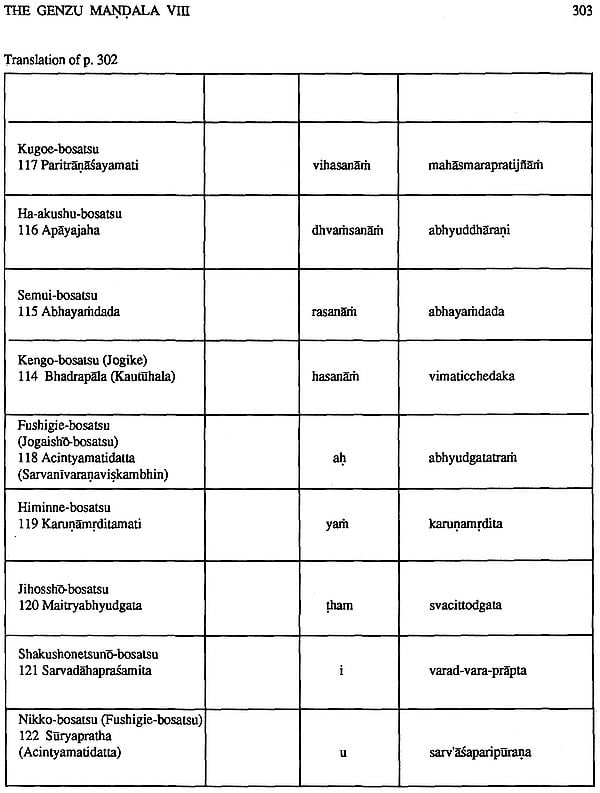

| 5 | The Genzu mandala | 174 |

| Descriptions of the Genzu mandala | 360 | |

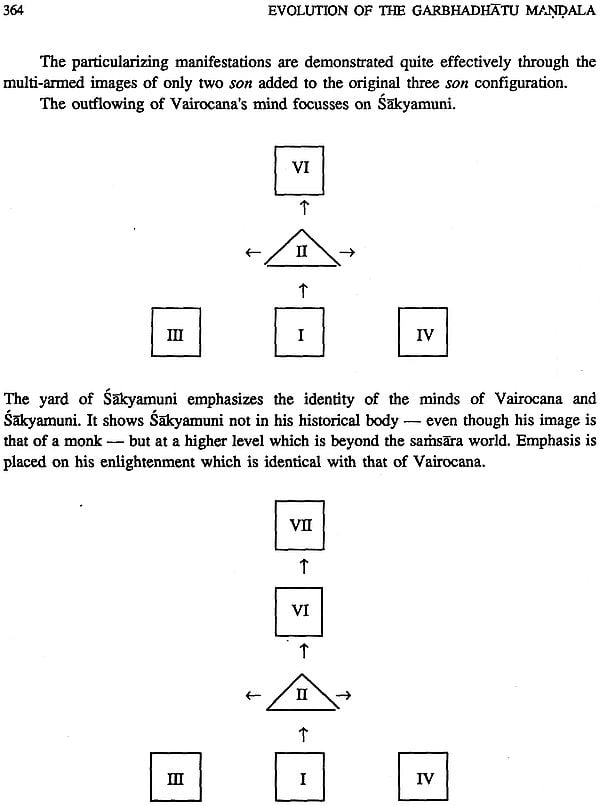

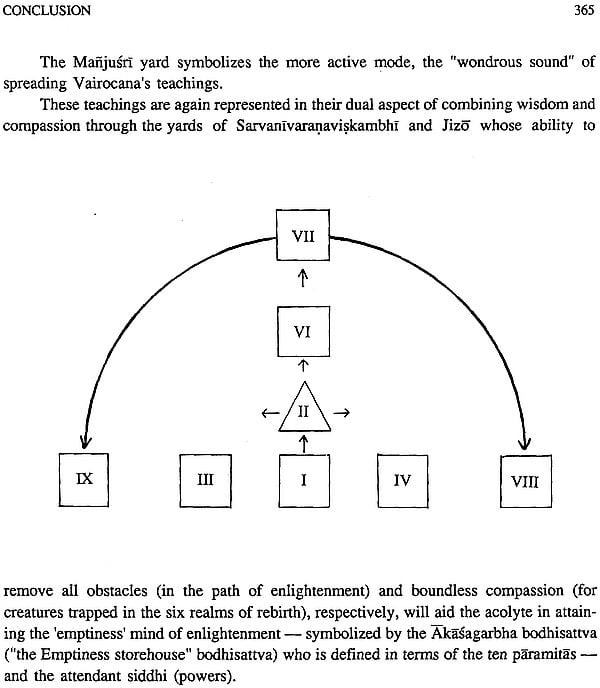

| Conclusion | 362 |