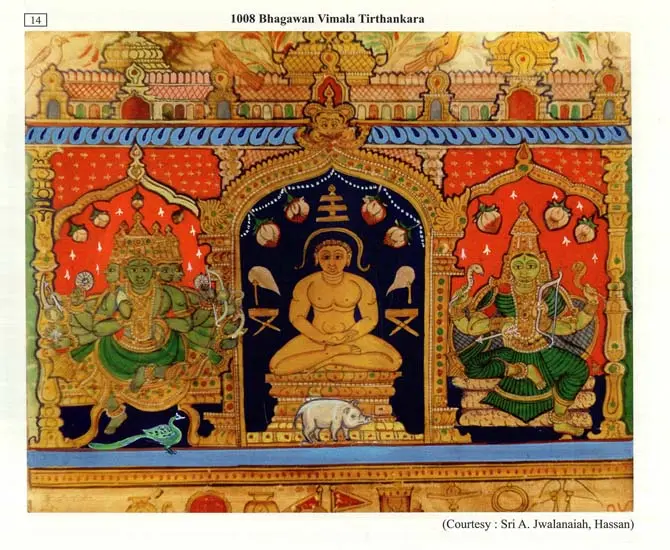

Sri Bhagavajjinasenacharya Gunabhadracharya Virchita: Jain Mahapurana (Set of 6 Volumes)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | UAI266 |

| Author: | Panditaratna Erthuru Shanthiraja Shastri and K. E. Radhakrishna |

| Publisher: | Panditaratna A. Shanthirajashastri Trust, Bangalore |

| Language: | Sanskrit Text With Translieration and English Translation |

| Edition: | 2020 |

| ISBN: | 9788193531839 |

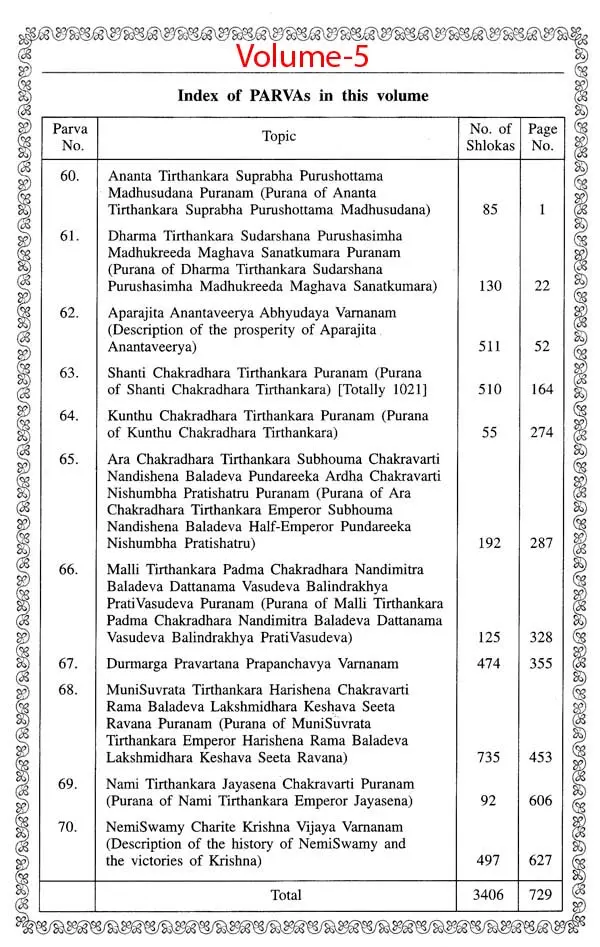

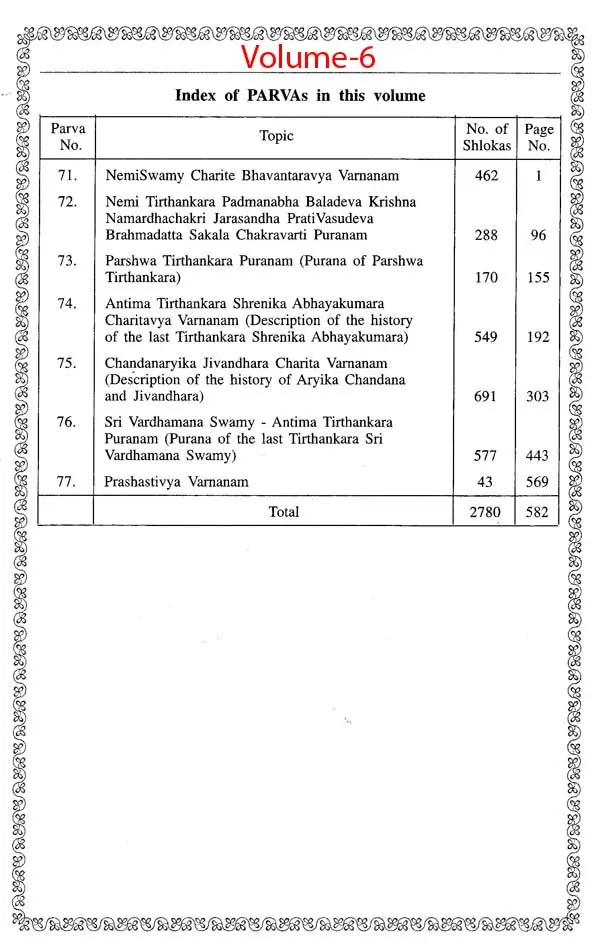

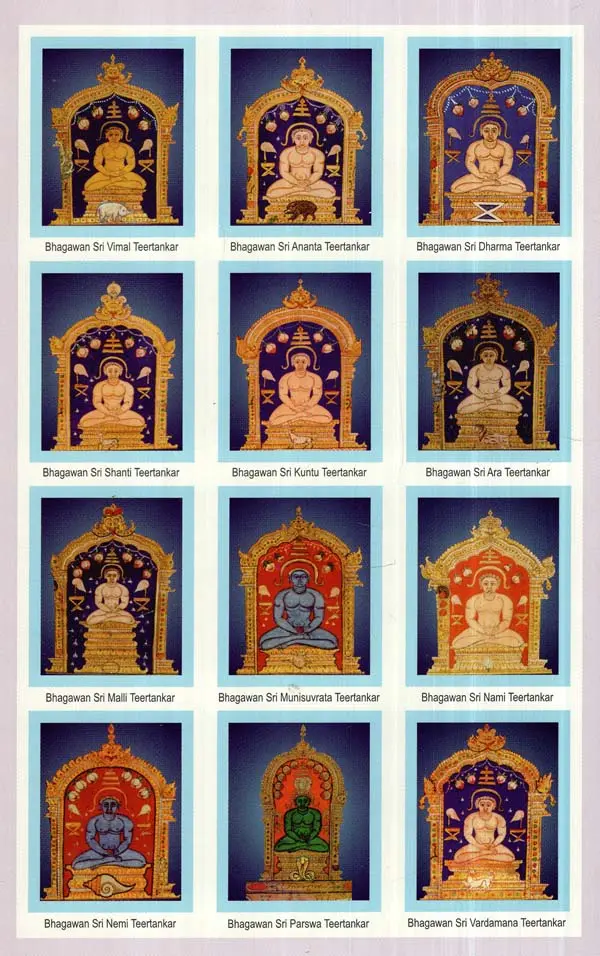

| Pages: | 4654 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 6.78 kg |

Book Description

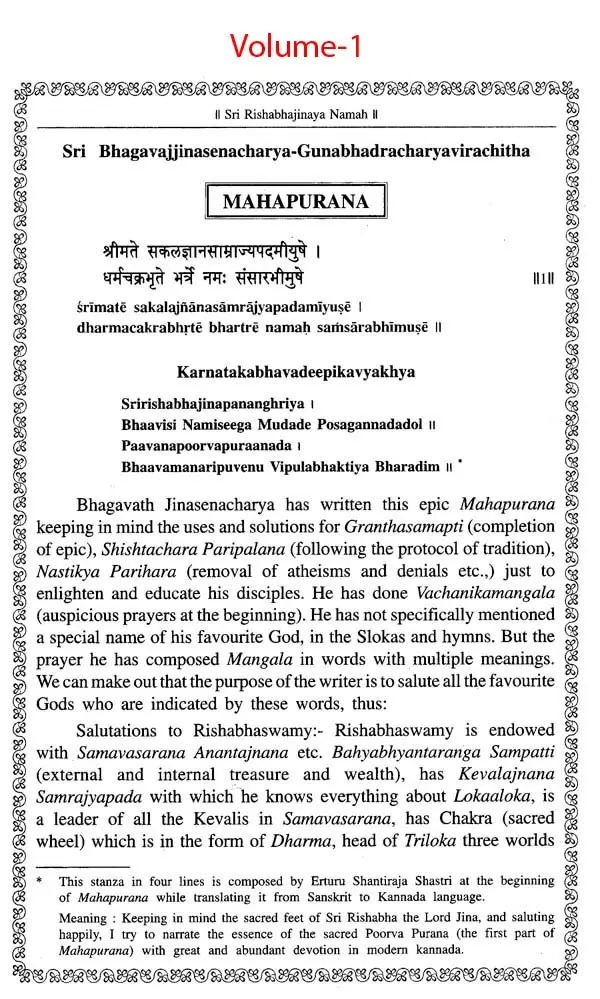

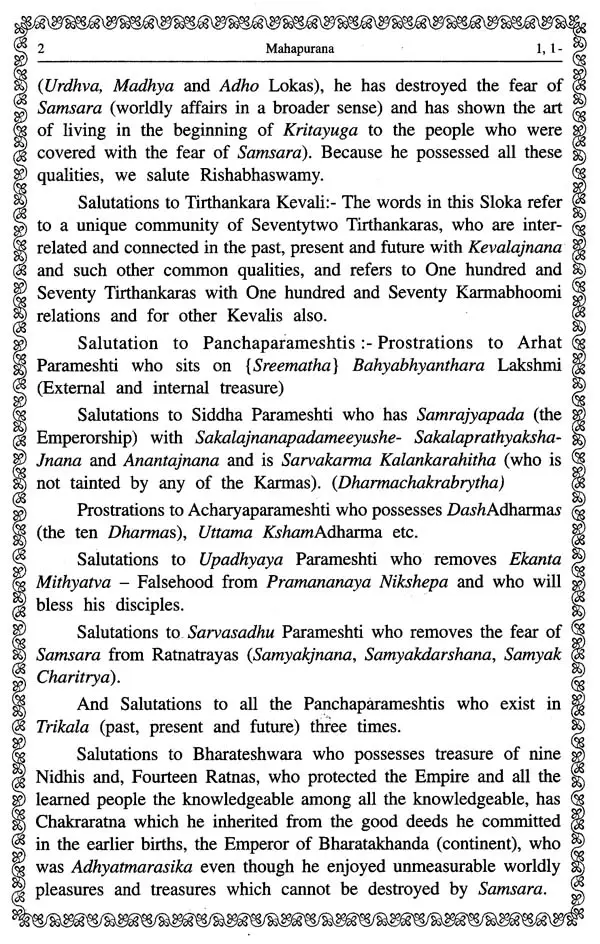

Erturu Shantiraja Shastriji - an ideal religious man, was known for his virtuosity, simplicity and great erudition. Dedicating his life for social service, he led a life of purity in its essence. Worldly fame, wealth, selfishness never polluted his mind. His life was dedicated to serve the society through literature. His area of work was wide and expansive. His service to the cause of literature was immense encompassing religion, ethics, prayers, philosophy, rituals, poetry et al. His collected works exceed more than 55 books and 77 articles. Mahapurana written by Acharya Jinasena and Gunabhadra, translated into Kannada is the crowning glory of his scholarship, Written in simple Kannada without tampering with the meanings of the original work, bringing out 20,000 Sanskrit Shlokas into Kannada is his Himalayan achievement. To the students of literature it is a great reference book. A brilliant scholar in Sanskrit, Prakrit, Hindi and Kannada, the founder of two journals 'Vishwabandhu' and 'Vivekabhyudaya', he was the only Sanskrit scholar honoured by Kannada Sahitya Parishat. He was honoured by the Royalty of Mysore as Asthana Maha Vidwan with the title 'Pandita Ratna'. Erturu Shantiraja Shastri was a great ideal soul honoured and respected by the society and scholars. He was a pure Jaina.

Prof Radhakrishna, a Professor of English Literature is a multi linguist scholar well-versed in Kannada, English, Sanskrit, Tulu and Hindi. A multifaceted personality, he has published 32 literary works, both critical and creative. His novel, Pretambhattara Nintillaru, Kavya 'Kannakadu', and poetry 'Gopikonmada' are the hallmarks in Kannada Literature. His literary works have won many Academy awards. He has produced musical ballets, is an Yakshagana Artist, a Theatre personality, and a Promoter of Arts and Culture. He is a nationally reputed educationist. As an administrator, he had held several important positions in the Universities of Karnataka as well as at the National Level. A brilliant and discerning scholar, he was awarded the honorary Doctorate from ka Open University Mysore and the prestigious Rajyostava from the Govt. of Karnataka. Translating/Trans creating the mega Mahapurana from Sanskrit/Kannada into English is his Magnum Opus.

Prof. Radhakrishna is a well-known Public, Cultural and Literary personality of Karnataka.

If the Kailasanatha temple at Ellora had not been excavated under king Krisna (eighth century CE), and the two great literary works, one in Sanskrit by saint-poet Jinasenacarya along with his disciple Guṇabhadracarya, and another in Kannada by poet Srivijaya had not been composed in the ninth century, despite its unparalleled political achievements, the Rashtrakuta rule would have been irrelevant to the literary and cultural history of the country. These events were not only the first of their kind in history, but also the last, because the attempts of this kind were never made later. Then the Rashtrakutas were ruling from Malkhed, the city of the same name in the present Kalaburagi District of Karnataka. Saint Jinasenacarya and poet Srivijaya were attached to king Amoghavarsa, the first as the royal guru and the second as the court poet. The former composed the first part of an epic titled Mahapurana in Sanskrit language, while the second composed a monograph on poesy titled Kavirajamarga in Kannada, Both laid the foundation of two distinct genres of literature.

The monastic language of the early Jains, like that of the early Buddhists, was Prakrit. As it varied from region to region, it was called by different names such as Sauraseni, Magadhi, Ardha-Magadhi, Paisaci, Maharashtrī, Pali and such others. The last name had a special relevance to the Buddhist writings. These dialects were used between the third century BCE and the third century CE, when both Jains and the Buddhists had consciously distanced themselves from the chhandas, a term with which they identified the Sanskrit language. They maintained this language policy till beginning of the common era, when the Kusans and Saka-Ksatrapas, two foreign tribes, invaded the country and ruled. over a substantial parts of it. The rulers of these dynasties, however, promoted Buddhist, Jaina and Vedic religions, and also Prakrit and Sanskrit languages. For the first time in history, the Buddhists and Jains began to write in the latter language, also mixing the Sanskrit with Prakrit under their rule. The credit for evolving a hybrid language, mixing Sanskrit with Prakrit and with Sanskrit, goes to them.

After the third century CE, the Jains deviated from the language policy of the Buddhists, and began to cultivate the vernaculars, especially in the south. They tried to reach out the local communities in their languages, retaining Prakrit for the monastic and ritual transactions. As the Buddhists began to lose their hold over the major part of the Deccan after the fourth century CE, it did not matter what languages they used for the monastic and public transactions.

The early cave engravings of the Jains in Tamil Nadu, thought scrappy in content, reveal the first compromise they made with a south Indian vernacular. But after about 400 CE, they picked up speed and issued more inscriptions in Sanskrit and regional languages than in Prakrit, using the local scripts which had emerged out of the Brahmi In fact, they became the chief promoters of three south Indian vernaculars, Kannada, Telugu and Tamil, in this order, and the main architects of ancient Kannada literature before the end of the first millennium CE. All this became possible because of the strong hold that Jainism had gained in Karnataka, and because of the presence of great saint-poets like Jinasenacarya and Gunabhadracarya here. If all the early literature in Kannada is Jain, it is because it was derived mostly from the great works of such acaryas.

Earlier to Jinasenacarya, the Jain writings in Karnataka were limited to the lithic stele and copper plates. The author of the Kavirajamarga recalls the names of about half a dozen prose writers, and a dozen other poets as his predecessors, but neither their works, nor their life details have survived. The legendary Sanskrit poets such as Bharavi, Kalidasa and Magha were, however, well-known to the poets of Karnataka. The impact of Kalidasa on the composers of the parasites of the Chaukyan king Mangalesa and of the Chaukya Pulakesi-II was very clear. Ravikirti the composer of the latter prasasti was the earliest Jaina poet of the lower Deccan, also of the country, to directly name Kalidasa as well as Bharavi (ravikirttihi kavitasrita kalidasa bharavi-kirttihi). The critiques have traced in this prasasti of 37 verses, set in 17 different chhandas, many echoes of the Raghuvamsa, Kumarasambhava Kiratarjuniya and Malavikagnimitra. In fact, Pulakesi's digvijaya is stated to be a replication of that of Raghu.

This discussion on Kalidasa would have been out place here had not Jinasenacarya unrelated himself from him. On the contrary, by integrating the entire Meghaduta in his Parsvabhyudaya (itiviracitametatkavyamavestyameghambahugunamapadosamkalidasasyakavyam), Jinasenacarya had demonstrated how deeply he had admired the classical Sanskrit poet.

The closing part of the third and the beginning of the fourth century was a crucial period in the history of Indian letters and literature. It marked the end of the monopoly of the Prakrit-Brahmi as well as the Sanskrit Prakrit hybrid language writings. Since Sanskrit did not have an individual script at this stage of its history, it had to depend on the Brahmi and some of the regional scripts, especially in the south. This explains why all the Sanskrit language epigraphs issued under the Early Kadambas, Gangas, Chalukyas, and such others, beginning from about fourth century, were written in the ancient Kannada (halagannada) script Not till the middle of the eighth century, when a pillar inscription at Aihole was engraved in two scripts Kannada and Nagari- do we come across the use of any other than the halagannada script for the Sanskrit writings here. In this background, if we have to make out the script used by Jinasenacarya and Guṇabhadracarya for the Mahapurana, it would certainly tilt more towards the Halagannada! There is also the testimony of the Kavirajamarga, that the homeland of the chaste Kannada language was bound by Puligere, Kupana, Kisuvolalu and Vokkunda Vankapura (or the present Bankapura) where Gunabhadracarya lived and completed the Uttarapurana was one of the Jaina strong holds in this region. But, in reality, did these âcăryas compose the Mahapurana in Kannada script, as almost all the Sanskrit writing had been done till the eighth century here, or in the Nagari script which was just emerging under the Rashtrakutas as, first in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, and then in Karnataka? No matter in which script was this written, undoubtedly the Mahapurana was the first Sanskrit language epic to come out of the Jaina poets in Karnataka.

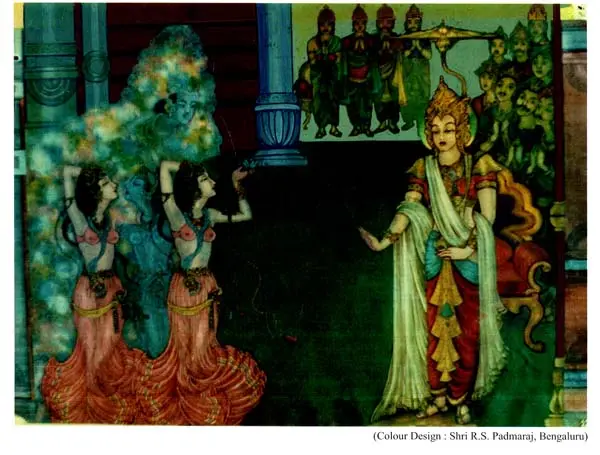

Mahapurana is a colossus, expansive literary work like an ocean. Its sweep is far and wide. One finds profound truth in its bosom. Words of wisdom adorn the text as it describes the fundamental truths of life. Its contents are encyclopedic in nature.

For many years in the past, the readers of Mahapurana understood it more as a narrative, analysing the various characters in the narrative and enjoying the details of the description of the events as they unfold. In reality the Mahapurana goes beyond this. It is deeper with ample opportunities for research and further understanding. Its potential for research is infinite as its canvas is so large. It contains social issues, deep philosophical revelations, thoughts on music art and aesthetics. The content of the text is varied and diverse. The description is vivid Mahapurana is a lexicon. It stands tall like a Sanskrit encyclopedia. Words are meaningfully woven into the Slokas. This magnamopus underlines the message of a peaceful tolerant society through non-violence. This message is eternal. It holds good for the past present and the future.

The lucid explanation of every Sloka has opened, the treasury of knowledge for every seeker. It is a researcher's cup of joy. In this age of science and technology it is indeed necessary to understand Mahapurana as a beacon light to find solutions to current issues of world peace, environmental protection universal brotherhood, nonviolence and so forth. Very few people have developed these insights into Mahapurana. Late A. Shanthirajashastry was a luminary and the people of Karnataka need to offer their salutations to him. He was honoured by the Maharaja of Mysore with the title of Panditaratna which is comparable to the Jnanapith award. The Kannada Sahitya Parishat has honoured him for his profound and versatile knowledge. This work has been published very neatly. With immense pleasure I express my gratitude to Sri S. Jithendra Kumar son of late Sri A. Shanthirajashastry, his other sons and the members of the Shanthirajashastry trust, Mysore and pray God bless them.