Studies in Origin and Development of Yoga (From Vedic Times, in India and Abroad, with Texts and Translation of Patanjala Yogasutra and Hathayoga-Pradipika) (Transliteration and English Translation) - An Old and Rare Book

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAH383 |

| Author: | Sures Chandra Banerji |

| Publisher: | PUNTHI PUSTAK |

| Language: | Transliteration and English Translation |

| Edition: | 1995 |

| ISBN: | 8185094926 |

| Pages: | 550 (4 B/W Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 8.5 inch x 5.5 inch |

| Weight | 630 gm |

Book Description

About the Book

The author has attempted to trass the origin and development not only of Rajayoga (de- signed to discipline the mind), but also of Hathayoga (aimed at keeping the body fit). He has also shown the relation of Yoga with Tantra and other systems of ancient Indian thought. The texts of the Patanjala Yoga and Hathayoga- pradipika, in Roman script, are followed by lucid English translation and illuminating notes.

The book highlights the importance of Yoga for the treatment of psychosomatic diseases. The global popularity of Yoga has also being dealt with.

Illustrations of some Asanas, a glossary of technical terms and an upto-date bibliography are some of the special features of the book. Both the general reader and the professional psychiatrist will find the book extremely useful.

About the Author

Dr. Sures Chandra Banerji (b. 1917), a Retired Professor of Sanskrit, winner of Rabindra Memorial Prize (1963-64), has dedicated him- self to the cause of Indology. A Fellow of the Asiatic Society, Calcutta, and a Life Member of Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune. he is connected with some other learned institution. He has authored more than fifty works on different aspects of indology, including A Companion to Sanskrit Literature, A Brief History of Tantra Literature, New Light on Tantra, Studies in Origin and Development of Yoga, New Perspectives in the Study of Puranas, A Companion to Indian Philosophy, etc.

Preface

A threefold motive prompted the author to undertake this work.

First, to have a first-hand idea of ancient Indian Yoga by the direct study of the Sanskrit texts. Second, to remove misconceptions about Asana, Pranayama, etc. from the minds of some of the trainers and trainees in yogic exercises and yogic therapy. It is reported (The Telegraph, a Calcutta daily, dated 10.9.90 ) that some Christians in Toccoa, Georgia, branded Yoga as 'devil worship'. On this ground, a Government-sponsored Yoga class in Toccoa is reported to have been cancelled. As Radhakrishnan says, there is a “popular confusion of the Yoga system with some of the repulsive practices of the Tantra cult and later adaptations of Patanjali's Yoga by fanatical mendicants.” (Indian Philosophy, II, p. 372).

Some people, led by a purely mercenary motive, run Yoga centres. They do not go deep into the original sources, and, therefore, are apt to misguide the neophytes. The Hathayoga-pradipika states (II. 17) that Pranayarna, wrongly practised, may cause painful diseases like asthma, hiccup, etc. According to the Vayupurana /xi. 37-60), yogic practices by the ignorant result in dullness, deafness, blindness, loss of memory, premature senility and other diseases, The translator of the Adyar Library edition \ 1972, reprinted 1973 of the Hathyoga-pradipika notes (in translation, p. 8) perhaps from his own experience, that a mistake in Hathyoga may end in insanity, even death.

Thirdly, this work aims at taking stock of the studies in, and practice of, Yoga in India and abroad at present.

Yoga has been very popular n t only in the land of its origin, but also in foreign countries, eastern and western, as will be evident from the section of this book, entitled 'Yoga and Foreign Countries'.

The tremendous popularity of Yoga has prompted the author of the present work to present the principal texts, in original of both Rajayoga and Hathayoga: As far as we know, there is no single work containing both these texts. As the Hathayoga-pradipika states (II. 76), perfection in Rajayoga is not possible without Hathayoga nor can the latter be perfected without the former. Thus, the two are complementary to each other.

With the foreign readers in view, we have given the Romanised versions of the texts of both Patanjala-Sutra and Hathayoga pradipika. English translation, with notes, has been given. The texts are, at places, too difficult to understand without explanatory notes, We have added such notes mainly based on the Vyasa-bhasya, occasionally adverting to other commentaries. We have avoided hair-splitting niceties and prolixity which are apt to confuse the general reader. Besides the major works, mentioned above, there are some short tracts or manuals of Yoga. We have given an outline of the contents of these compendiums which appear to be short useful guide-books.

Besides the Yoga practioners, there are scholars of Yoga. Keeping their needs in View, we have dealt with the origin and development of Yoga since the earliest times. We have also dwelt on the relation between Yoga and other systems of thoughts in India, A comparative idea of Yoga and western psychology has been given.

In several appendices, we have separately dealt with, in some detail, the Asanas, Prayanama, Mudras and meditation for ready reference, keeping in view the needs of the practitioners of Yoga.

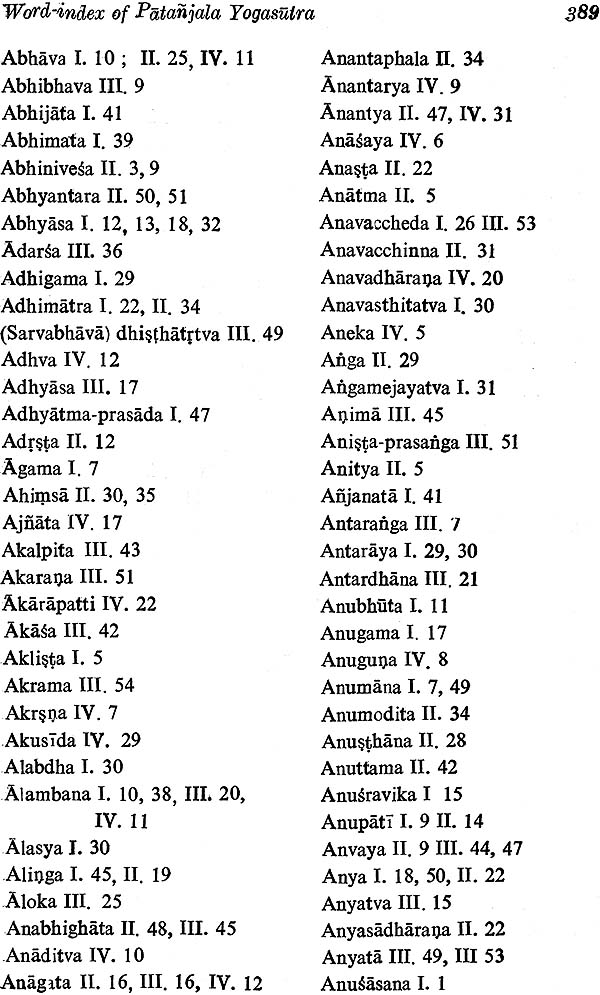

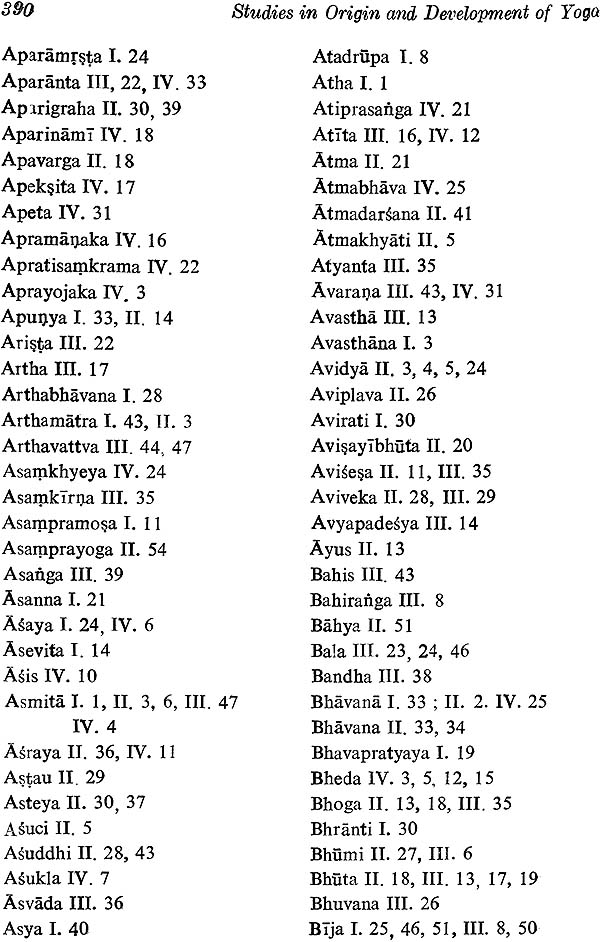

We have given, a word-index to the Yogasutra: In a Glossary, which is fairly exhaustive, we have noted the meanings of difficult words and technical terms. The Bibliography contains information about both text-editions and studies.

The labour of the author, spread over a long time, will be rewarded if the work goes some way in presenting Rajayoga and Hathayoga in their proper perspectives, and in dispelling wrong notions about them.

It is hope I that a careful study of the work will show the reader the way of preparing the mind for getting peace and tranquillity of mind on a permanent basis, and will convince him of the utter futility of Cinema, the media like TV etc., and the most perncious alcoholism and drug-addiction in generating genuine and lasting inner calm which is a healing balm to the mind lacerated by the travails and turmoil of modern life; these provide only a temporary escape, and that also at a heavy cost in the form of strain to eye- sight, and damage to the internal organs.

The author is extremely grateful to his wife, Sm. Ramala Devi and his two daughters, Chhanda and Sarmila, for helping him in various ways to make his long-cherished dream a reality. By under- taking to publish this work, Sri Sankar Bhattacharya, owner of Punthi Pustak, has again demonstrated his genuine love for indology.

YOGA-NATURE AND CLASSIFICATION The term 'Yoga', which is multivalent and derived from root Yuj, generally means union. In Sanskrit literature, it has been used in a variety of senses. For example, the Bhagavadgita uses it (ii. 48) to mean sole desire for Supreme Divinity (paramesvaraikaparata- Sridharasvamin). In ii 50 of the same treatise, Yoga denotes skill in work (Karmasu kausalam). In IV. 1, 2, 3 Yoga means Karmayoga (desireless action) and Jnanayoga (acquisition of true knowledge). In VI. 16, 17, the term means Samadhi in which the mind is united with Atman. In VI. 23, Yoga means a state of mind which, having realised the Supreme Being, is not disturbed even by great suffering. In ii. 48 and vi. 33, 36, Yoga means samatva or equanimity i.e. indifference to pleasure and pain.

In ix. 22, as also in some other works, Yoga means the acquisition of what has been gained (alabdhasya labhah). In ix, 5, x. 7, xi. 8, the Yoga of the Lord is characterised as His miraculous power (vibhuti).

In arithmetic, Yoga means addition. In astronomy, it means conjunction, lucky conjunction and conjunction foreboding danger, etc., a combination of stars, name of a particular astronomical division of time (27 such Yogas, are usually enumerated; e.g. Amrtasiddhi, Vyatipata, etc.

In the Upanisads, Yoga generally means union; union of the jivatman with Paramatman- But, the idea of union is expressed in the Mundaka Upanisad by the word Samya and not Yoga.

In the Ys., Yoga does not mean union, but only effort. as Bhoja holds, this term means viyoga or separation of the from Prakrti.

Patanjali, in his Ys. (i.2) defines Yoga as sittavrttinirodha (suppression of mental functions). Radhakrishnan rightly says (Indian' Philosophy, p. II, 337) that by Yoga Patanjali means effort, not union.

The Devala-smrti says- Visayebhyo nivartyabhipreterthe manasovasthapanan Yogah. Yoga means fixing the mind on the desired object (withdrawing it from the objects of sense. According to the Daksa-smrti (vii. 15), mukhya yoga (principal Yoga) is as follows:

vrttihinam manah krtva ksetrajnah paramatmani

ekikrtya vimucyate yogayam mukhya ucyate

One who is aware of the soul, having turned the mind, which is rendered devoid of functions, solely to the Supreme Soul, is liberated; this is called principal Yoga.

The Visnupurana(vi. 7.31) defines Yoga- atma-prayatna-supeksa visista ya manogatih

tasya brahmani samyoga yoga ityabhidhiyate

The connection of that special course of the mind, which depends upon one's own effort, with Brahman is called Yoga. All the above definitions of Yoga have been quoted by Apararka on the Yajnavalkyasmrti (iii. 109) and in Laksmidhara's Krtya- kalpataru (Moksa), p. 165. Apararka defines Yoga as

jiva-paramatmanor- abhedajnanam visayantara-sambhinnam yogah.

Yoga means the cognition of the identity of the individual soul with the Supreme Soul, which (cognition) is not distracted by any other matter.

Thomas says (Hist. of Bud. Thought, p. 43, note 2) that the primary denotation of Yoga is discipline, and the secondary meaning is 'union' as the result of Yoga. Edgerton also holds the same view (AJP, XLV, pp. 1ff.). Carpentier has tried to show that, in the Mahabharata and even in later treatises, Yoga does not mean 'Union' (ZDMG, LXV, pp. 846f.).

Yoga is broadly divided as Rajayoga2 (yoga par excellence) and Hathayoga. The former is concerned mainly with the mind, and deals with various processes for controlling and calming it. The latter is a particular mode of Yoga, so called as it is very difficult to practise. It is concerned mainly with the body, and deals with various means of keeping it fit. The term haiha is a combination of Ha (Prana) and Tha (Apana). Their Yoga or union, called Hatha- yoga, is effected by Pranayama(q.v.)

Besides the above, several other prominent kinds of Yoga are mentioned by later writers, e.g.

Mantra-yoga, Laya-yoga, Tantra-yog(L, etc. 4 Besides these, Samadhi (q.v.i, Unmani (q.v.), Manonmani (q.v.), Amaratva (immortality), Taitva (truth), Sunyasunya (void, yet non-void), Paramopada (the highest or supreme state), Amanaska (mindlessness, i.e. transcending mind), Admaita (non-duality), Ni'ralamba (without support), Niranjana (devoid of impurity), Jivanmukti (liberation in life), Sahaja (q.v.) and Turya (q.v.) are all synonymous with Rajayoga (vide Ha~hayoga-p1'adi.pika, IV. 3, 4).

All the various types of Yoga are rooted in the common source of Patanjala Yoga, but each lays stress on a particular aspect of discipline.

Besides Rajayoga and Hathayoqa, SrT Aurobindo mentions Jnanayoga, Karmayoga and Bhaktiyoga.

The four stages of Yoga, in later literature, are called ,Arambha, -Ghata, Paricaua and Nispatti.

In another way, Yoga is classified as Samprajnata and Asamprajnata. The former is fourfold according to the different objects of contemplation; viz, Saoitorka; Savicara, Sananda and Sasmita.

Yoga has been defined as Cittavrtti-nirodha. Cittabhumi or mental life is constituted by the qualities of Sattva, Rajas and Tamas. Its different conditions depend on the different degrees in which the above qualities are present and operative in it. These conditions are called Ksipta (restless), Muqha (torpid), Viksipta (distracted), Ekagra: (concentrated) and Niruddha (restrained), The first three are not at all suitable for yoga. The last two are conducive to yoga. In the Ekagra condition, citta is free from impurity of Rajas, and Sattva is perfectly manifested. It marks the beginning of protracted concentration of citta on any object so that its true nature is revealed. It paves the way for the cessation of all mental modifications. In this condition. citta continues to think or meditate on some obejct. So, even in it the mental processes are- not totally arrested. It is in Niruddha level that there is complete' cessation of all mental functions including Ekag1'ata. In this condition, the succession of mental states and processes are fully checked and citta is left in its pristine, unmodified state of calmness and tranquillity. The Ekagra state, when permanently established, is called Samprajnata yoga, also known as Samprajnata Samadhi or Samapatti. The state of Niruddha is called Asamprajnata Yoga or Asamprajnata Samadhi. Both the above kinds of Samadhi are- known by the common name of Samaclhi-Yoga.

Contents

| I | Introduction | 1-122 |

| II | Works on Yoga-Major Works | 123-324 |

| III | Goraksanatha and his Order | 325-333 |

| Appendices | 335-385 | |

| Word index of Patanjala Yogasutra | 387 | |

| Reference | 397 | |

| Glossarial Index | 423 | |

| Selected classified Bibliography | 476 | |

| Miscellaneous works | 501 | |

| Addendum | 515 | |

| Index | 517 |