Unfolding Contemporary Indian Textiles

Book Specification

| Item Code: | NAK643 |

| Author: | Maggie Baxter |

| Publisher: | Niyogi Books |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2015 |

| ISBN: | 9789383098835 |

| Pages: | 187 (Throughout Color Illustrations) |

| Cover: | Hardcover |

| Other Details | 12.0 inch x 9.0 inch |

| Weight | 1.20 kg |

Book Description

About the Book

'Unfolding' is a timely and vital examination of how the rich and diverse textile craft traditions of India have been adopted/adapted in the 21st century. The author looks at new interpretations made within the current cultural landscape by designers who dare to take steps into the unknown: Traditional techniques and motifs are reworked in atypical, up-to-date ways, creating a fresh new visual language that is still identifiably Indian.

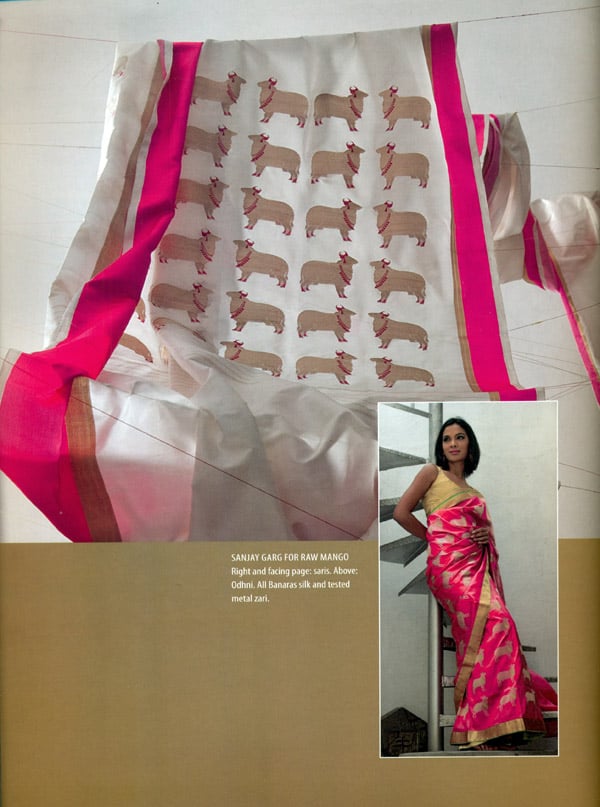

Separate chapters examine the work of 23 designers and artists in terms of craft revival, surface treatment, texture, minimalism, and narrative. Raw Mango, for example, glories in the drenched colour of the cones of pure colour pigments found in Indian markets creating saris of extreme colour that are both minimalist and overpoweringly intense, while bai Iou reposition the delicate motifs of Bengali jamdani, scaling them up into bold, oversized, geometric shapes. In Kutch, architect and designer Kirit Dave deconstructed the rigidly arithmetic system of ikat into deliberate fracture and dissonance, whereas for Ravage disharmony is achieved by piercing, fraying and embellishing fabrics to make highly theatrical garments that simultaneously allude to bazaar kitsch and Punk subculture. Popular culture is celebrated with Play Clan's madcap digital prints and hand embroideries and Good earth's unashamedly romantic delving into Bollywood, history and legends.

The last chapter looks at the small but growing number of Indian artists such as Mithu Sen, Manisha Parekh, and Parul Thacker for whom fibre and fabric are an integral part of their studio and gallery practice.

About the Author

Maggie Baxter is an Australian artist, writer, independent curator, and public art coordinator. She first visited India in 1990 and has since been a frequent visitor, particularly to Kutch, in Gujarat, where she maintains a textile arts practice that uses traditional textile techniques as media for contemporary art. She has exhibited regularly since 1984 in both group and solo exhibitions in Australia, India, Japan and UK. She held her first solo exhibition in India at the Visual Arts Gallery, India Habitat Centre in December 2004, for which she won their award for the Best Design and Craft Show 2004. In Australia she works primarily in the area of public art coordination managing a significant number of large-scale individual integrated artworks for major urban redevelopment projects.

Introduction

Everyday in homes, workshops, villages and factories all over India unimaginable quantities of amazing textiles are being produced. Given this plenitude and the potential enormity of the subject, even when confined to more experimental expression, the two big questions that had to be asked to get this book underway were - where to start and where to finish.

Both questions had to be addressed in tandem, but if anything, the 'where to finish' achieved clarity earlier as the parameters were defined.

Artists and designers come to India from all over the world specifically to access everything that the Indian textile industry has to offer from bulk production to specialist export houses making exquisite hand embroidery and hand beading. Some, like myself, come to work at the village level with archaic textile techniques that are no longer available elsewhere. The first decision was not to include any 'fly in, fly out' designers but to limit the book to those living and operating businesses in India. I also decided not to venture into large industry or export companies, but to concentrate on Indian designers fabricating from their own workshops or outsourcing small-scale, generally handcrafted production to make textiles primarily for the Indian market. However, in the 21 st century it would be remiss not to include digital printing onto fabric.

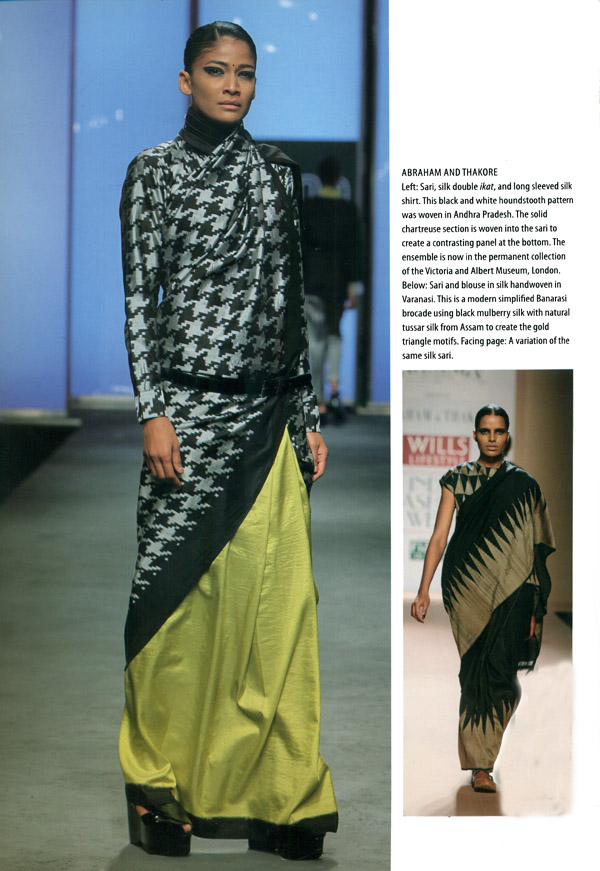

This book isn't about fashion, but given the symbiotic relationship between fashion and textiles, many of the designers discussed in the book are fashion designers. It is pleasing to see the tradition of uncut cloth thriving in new ways as young Indian women actively look for new interpretations of the sari and ways of wearing it.

No doubt as a reflection of my own background and in keeping with a broader arts based trend of referring to Fibre-Textiles as a specific genre, however loosely defined, I have extended the book to include fibre (Bashobi Tewari's GreenEarth) and the inclusion of textiles in art gallery centric practices (Chapter 8: Crossing Over).

Considering how Indian textiles might be defined as contemporary immediately leads to vague and imprecise concepts that are difficult to pin down. The word contemporary most simply means current - and most of the textiles illustrated and discussed are that by virtue of being seen in the designers' workshops when I went there. A small number are from the past 30 years but were chosen from individual designers' overall output. I have made no attempt to engage in modern historical research.

In the world of art and design the word contemporary and experimental are much more loaded notions and open to subjective interpretation. No one would assume that a textile with a regular repeat print of small butas would be termed contemporary even if printed today. The word implies new interpretations made within the current cultural landscape by designers who dare to take steps into the unknown.

Yet India is a two-speed society where the pace of change and accumulation of new ideas and influences in villages and small regional centres can be extremely slow compared to the large cities. This is especially so if there is inadequate access to education and technology and limited ability to travel, even to the next village. In rural India the idea that a design is contemporary can only be assessed within a socio-cultural framework that acknowledges this. Essentially, it all depends on your starting point, and radical shifts in motifs, layouts, or colours on fabrics produced in one village may not be immediately recognized as such in the big wide world outside that small geographic area. That lack of recognition does not detract from the importance of those changes or the daring actions of those who made them.

There are designers in India who focus on the perfection of craft, and we should be thankful that they do, as they keep those techniques alive at the pinnacle of the artisan's skill. Although experimentation and perfection are not necessarily mutually exclusive, perfection by itself is not the focus of this book and, as it turns out, some featured works are purposefully imperfect.

Parameters (lightly) set the question about where and how to start the research. Little has been written on contemporary Indian textiles or fashion beyond brief articles in newspapers, fashion magazines and on line reviews and blogs. Although I knew or knew of some of the designers in the book, on the whole research was generally through informal means.

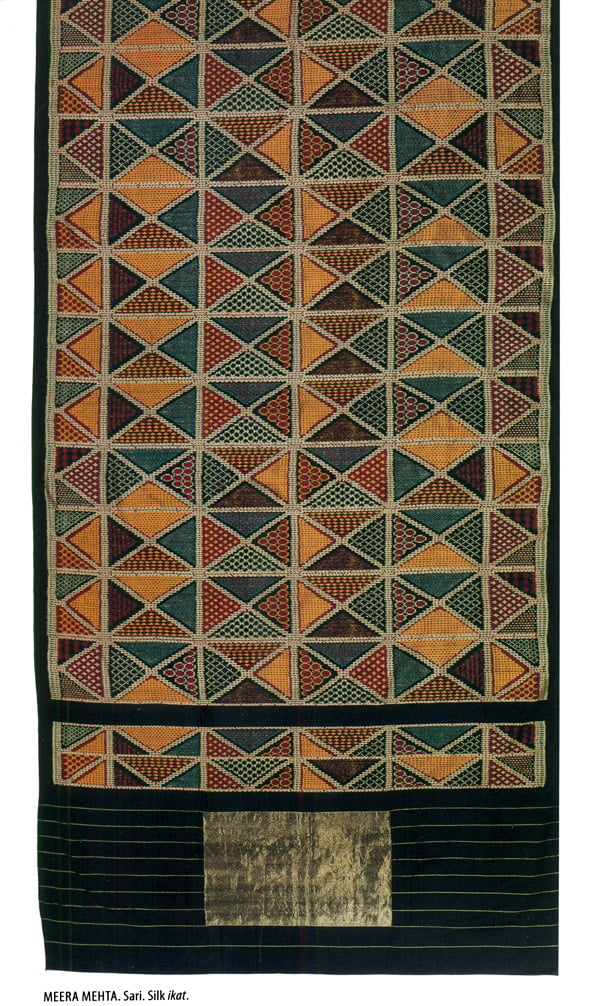

I discovered that weddings and engagement parties are excellent sources of sari research and I am grateful to my Indian women friends for being intrepid in their choices. It was at such an occasion that I first saw a bai Iou sari. I was surprised to see this particular friend wearing a sari in the first place, but she had taken it into the direction of shock and awe, wrapping herself in a design of such oversize proportions that the jamdani looked almost African. Her sari blouse was cut away in a razor back, like an athletic T-shirt, and very much in keeping with current global street fashion, she deliberately allowed thin bra straps and a tattoo to show. In that one ensemble she had summed up all that this book is about: the evolution of an ancient tradition into a 21 st century idiom. At another function I was stopped in my tracks by a truly extraordinary ikat sari by Meera Mehta that was both boldly geometric and delicately soft in the detail. There and then I was on the trail of both designers.

Friends and associates were kind enough to give me suggestions and leads all of which I followed up but not all of whom, in the end, I included. Apart from some of the artists in the final chapter, where I have relied on information provided by their gallery, I have met and interviewed all of the designers in the book and what I have written is based on those discussions. I also came across the work of some designers that I would have loved to include but tracking them down proved elusive.

In relation to my own work in Kutch I am fond of quoting a Talmudic saying that I found years ago in a Hali Annual: 'We do not see things as they are. We see things as we are:' The same applies to this book. Although I have tried to present a balanced selection from at least the major centres if not the entire country, inevitably the final choices reflects my own perspective as a curator and practising artist and designer from outside of India, albeit mitigated by a long association with the country at the grassroot level. Given the scope of the subject matter, it is certain that anyone else writing on this subject would have another viewpoint and a different mix of artists and designers.

If there is a slight bias towards Kutch in the state of Gujarat, this is not entirely due to it being the region of India with which I am most familiar. The proximity of Kutch to Ahmedabad, and therefore the National Institute of Design (NID) has meant that since its inception in 1961, students of textiles and fashion have gone there regularly for fieldwork, research and internships. Some of India's better-known designers have continued this relationship - even though travel is far less convenient from Delhi than Mumbai or Ahmedabad. Designers in Kolkata and Bangalore tend to stay local.

This ongoing interchange with visiting designers has given local Kutchi artisans the confidence to take control of the direction of their craft without relying on others for input. The Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya Design Institution for Traditional Artisans, which American anthropologist and long time Kutch resident, Dr Judy Frater, set up in 2005 specifically to teach design and marketing skills to up and coming artisans, has ensured the continuation of this to the current and forthcoming generations. It is a measure of Dr Fraters' stature that she has attracted visiting lecturers from national and international design schools to give their time and expertise. This is a model that could be repeated across India.

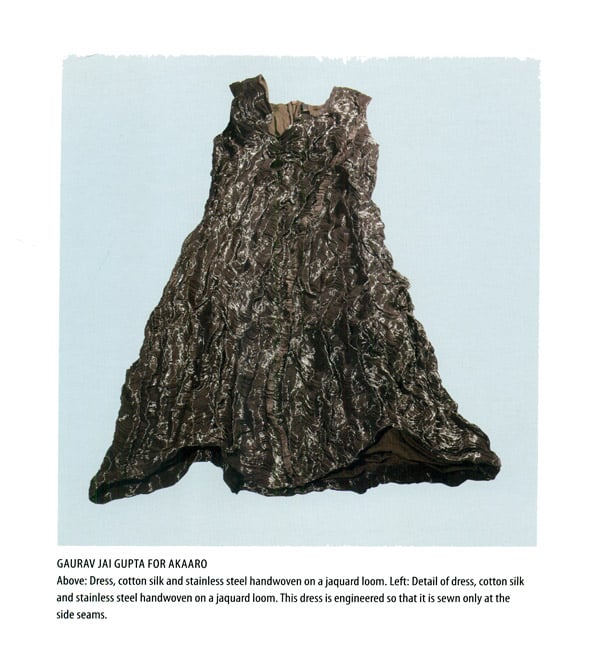

The book is arranged thematically rather by skill or technique. This inevitably leads to some overlap especially in chapters that run consecutively. The first two chapters are entrenched in villages, where designers are actively engaged in the revival of skills and techniques as a mechanism for micro-economic development or to open up new markets by reinterpreting what is available. As the book progresses the emphasis morphs into explorations of surface print, tie-dye and stitch, and then texture where designers manipulate, construct and deconstruct cloth into a tangible three-dimensionality. Next, and more quietly, the ascetic sparseness of Minimalism is discussed within an Indian context before loudly celebrating new interpretations of the popular and populist narrative tradition. The book finishes in galleries looking at artists for whom textiles and textile practices are integral to their art practice. This chapter also briefly discusses why the genre of Textile-Fibre Art, as understood internationally, has barely taken hold in India.

I have attempted to place the work of some designers within a wider context of international art and fashion movements and in this have been supported by the information they provided regarding external influences. Yet whatever is being absorbed from elsewhere, there is an overwhelming sense of an Indian cultural identity. 'Indian-ness: however it is interpreted and manifested is both the driving force and the outcome, and anything external is another layer onto this, not a substitute for it. The Indian village remains a constant presence throughout as even those designers and artists whose direct interaction with village artisans is minimal or nil openly acknowledge that the daily life and popular culture of villages and marketplaces influences them in all kinds of ways obvious and oblique.

Indian textile designers are the envy of the rest of the world because they continue to have close, easy contact with all manner of hand production and crafts rarely available elsewhere. Although it may take time and patience to build up successful working relationships between designers and artisans, the pool of available skilled talent is so wide that it seems that any dream and idea can be woven, embroidered, printed, beaded, or sewn. Limitations are only in the mind. There are many traditional artisans represented in this book whose talent and expertise combined with a determination for self-expression and self-determination has empowered them to become artists and designers in their own right. Across India, it is the numerous and often nameless skilled craftsmen and women who produce the vast output of textile production. They are the real heroes and heroines of this industry and they are acknowledged and honoured for their contribution to the textile adventures described in this book.

Contents

| Introduction | 7 |

| Survival and Revival | 13 |

| Re-view | 35 |

| Surface | 61 |

| Texture | 79 |

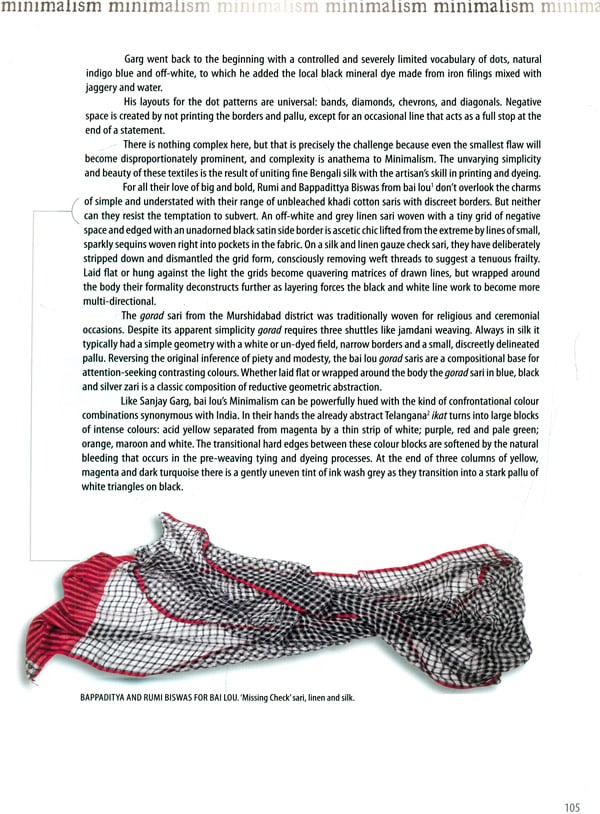

| Minimalism | 103 |

| Narrative | 131 |

| Crossover | 149 |

| Biographies | 174 |

| Bibliography | 179 |

| Glossary | 181 |

| Image Credits | 184 |

| Acknowledgements | 185 |

| Index | 186 |