The Upanishads- Deciphering Their Goal, Purpose and Content (Reflections on Existence)

Book Specification

| Item Code: | AZB654 |

| Author: | Sushila Krishnamurthi |

| Publisher: | True Living Foundation, Rishikesh |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2012 |

| Pages: | 402 |

| Cover: | Paperback |

| Other Details | 8.5 x 5.5 inches |

| Weight | 460 gm |

Book Description

This is an in-depth and revealing book, forming a set of contemplative and analytical writings communicating the profundity of the Upanishadic message with insight and clarity. It is as much for seekers of freedom and wholeness, as for thinkers on existence.

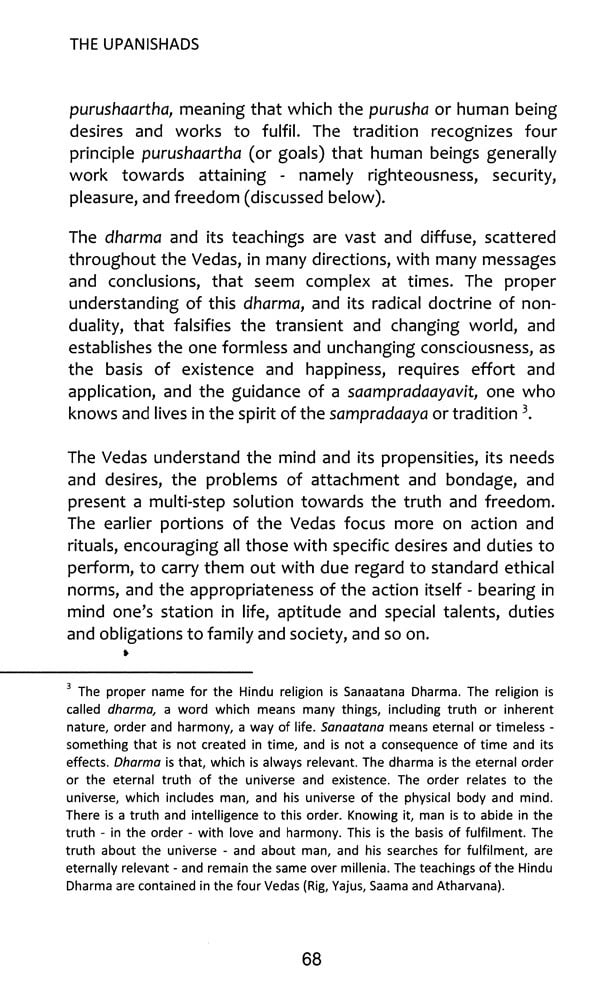

The nature of the Self forms the main subject matter, and the Upanishadic paradigm for understanding existence and happiness in the truest dimension, is critically discussed and elaborated upon. Existence is consciousness - the Self is pure consciousness - free from all limitations. Core human nature is limitation-free consciousness - timeless and all-pervasive. It is the quintessence of intelligent thought and feeling, as well as of love and creativity. Knowing oneself in this dimension is vital, in order to overcome the divisive tendencies of the mind, which put one in bondage and limitation. Spirituality is the universal human urge for wholeness and oneness, and the desire to discover the limitless being in oneself. It requires knowledge and understanding, along with dedicated application, for proper expression and fruition.

How the Upanishads deliver the truth of existence, what is the Self and its relation to God, what is the mechanism of happiness and sorrow - these are some of the crucial questions that find answers in this book. Despite the technical nature of the content, the author’s personalized and contemporary communicative style ensures that the reader remains connected at all times. It is a must-read for all wanting to know about the self and happiness.

The author has spent the last two decades on ‘self-oriented’ Vedantic study and analysis, and now lives in Rishikesh reflecting, teaching, and writing on the Vedanta. She is the founding Chairman of the True Living Foundation India, a non-profit-making organization dedicated to the promotion of awareness and education on true living and well-being.

The author's educational background includes a PhD in Biochemistry from the University of London, UK, where the author was engaged in teaching and research in the area of blood platelets and thrombotic disease, for over a decade during the 1970s and 80s. Following some 200 or so publications in the space of eleven years of teaching and research, the author retired from her university faculty position at the age of 32, to live a different type of non-competitive and contemplative life.

This book is the author's first publication. Although several other books have been written and not found their way to the printing press yet.

When I quit my research and teaching position as a UK Medical School Senior Lecturer in 1990, friends, colleagues, family, and all those around me, said I was burned-out. 'Burning out' was not a fashionable thing then, and is probably not now either. For it means you have lost out somehow. You cannot compete in the big, wide world any more. You can no longer be a high achiever, or a rich and successful person.

This labelling and covert (if not overt) condemning process that I had to endure, took its toll initially, on my resolve to carve out a better and more satisfying life for myself. It ate into my confidence, and clouded my clarity regarding why I quit, and what it was that I disliked most about the high-pressure job I was holding - with its deadlines for project completion, its ceaseless demands to 'publish or perish', and the strains of having to find funds for basic research, at a time when commercially-orientated research received most of the funding.

All I could do was feel, and I knew I did not feel good about any thing. I had had enough of commerce and competition. Fighting to survive, competing to be better than others, looking always to acquire and secure for oneself, finding little time to enjoy the rewards of hard work - these were things that were beginning to wear me out. If this was burning-out, so be it. I enjoyed the challenge of designing novel research projects, the thrills of discovering new little truths; but disliked intensely the competitive atmosphere and overt unfriendliness between rival research groups at work. I knew little about what would make me happy at the time, except that I wanted to work on music, my life-long passion, which having been relegated to the status of part-time hobby, had so far received less time than it deserved.

Soon I found myself in a remote farmhouse in south-west France, in a hamlet with no more than fifteen people - out of which only one person spoke English, with whom I could communicate. Some months into my French retreat, and with hours spent on music (Indian classical), I found my peace. Here there was no society that criticised and condemned, no lofty `success standards' to live by, no rivals to succeed against, no pressure to achieve, except whatever pressure I would put on myself to do and make something of my life. Gazing at the sheep roaming on the fields adjacent to my farmhouse started up a natural and involuntary dilution and erasion process - a dilution of external and self-imposed pressures to be and do something, and a slow but sure erasion of the many false desires that were clogging up my mind. I had heard time was a great healer, but did not realise until then that time heals by erasing unwanted and false items from the mind, both 'desktop and hard-disc'.

Was this enough ? Would this healing be enough to give me a new direction and purpose to life ? Did I want to go out and be a music performer, something I had done on and off as an amateur, even through my research days ? Somehow the idea of doing music as a profession, to please and entertain people, for the sake of making a living, seemed distasteful and unmotivating. Music was always a love - a passion and liking for the beautiful and extraordinary. I could not get into the idea of selling my music, performing to please and entertain others, when the primary purpose of pleasing and soothing myself, was already being served through my practices at home.

The answers to many such conflicts and questions came from the Vedaanta, eventually and gradually. My first brush with the Vedaanta came from Swami's Vivekananda's writings - and this great thinker's searches for the truth and fulfilment, found an echo in my heart. Soon I was going through writings from Ramana Maharishi, and all of a sudden I was getting inspired to take up serious study of the Vedaanta. I wanted to delve into the essence of the Hindu way of life and thinking, which I came to know revolved around self-knowledge and mental development, with freedom and happiness as the prime goal for every mature thinking person. An ancient verse in Sanskrit inspired me to learn and know more.

`The mind is the only cause of bondage and freedom - the only cause of sorrow and happiness'

Sorrow and happiness

Shokam tarati aatmavit - is an oft quoted statement from the Chaandogya Upanishad (7.1.3) - which literally means one who knows the self moves beyond sorrow - he/she is unaffected by the sorrows of life. The Bhagavad Gita also opens its discourse by stating that those who know the truth, do not allow themselves to fall prey to sorrow in its many manifestations.

All texts say the same thing. The mind that thinks not in true and objective ways, but does so in subjective and biased ways, is a sitting target for sorrow. There is no large-scale sorrow as such out there in the world, despite the fact that certain situations such as death, disease, and deprivation are matters that cause universal sadness. Events happen, things are made and destroyed, people come and go - not knowing how to handle changing thoughts and emotions, and changing external events, that please and displease alternately, puts the mind in a state of perpetual turmoil and confusion. This is the only reason why there is large-scale and sometimes uncontrollable escalation of sadness and depression. The wise ones see things clearly and objectively. They neither grieve nor rejoice over transient happenings too much.

**Contents and Sample Pages**